Back to selection

Back to selection

“I Wanted to Tell a Story Where the Atmosphere Was So Severe That It Literally Consumed the Movie”: Jeffrey A. Brown on the Environmental Horror of The Beach House

The Beach House

The Beach House In his final book, The Weird and the Eerie, critic and theorist Mark Fischer differentiates between “the weird” and the supernatural as it appears in both literature and film. For example, the supernatural world of vampires, writes Fischer, “… recombines elements from the natural world as we already understand it….” These supernatural stories are contrasted with fictions based around suggestions and byproducts of natural phenomena, such as black holes. “… The bizarre ways in which [a black hole] bends space and time are completely outside our common experience,” Fischer writes, “and yet a black hole belongs to the natural-material cosmos — a cosmos which must therefore be much stranger than our ordinary experience can comprehend.” When, in a work of weird storytelling, a portal opens to some sort of unexpected phenomena, and the world changes, man’s place in the universe is then radically decentered — a perspective shift that must be honored by the narrative itself. As horror writer H.P. Lovecraft, quoted by Fisher, wrote to the editor of a magazine titled Weird Tales in 1927, “…all my tales are based on the fundamental premise that common human laws and interests and emotions have no validity or significance in the vast cosmos-at-large.”

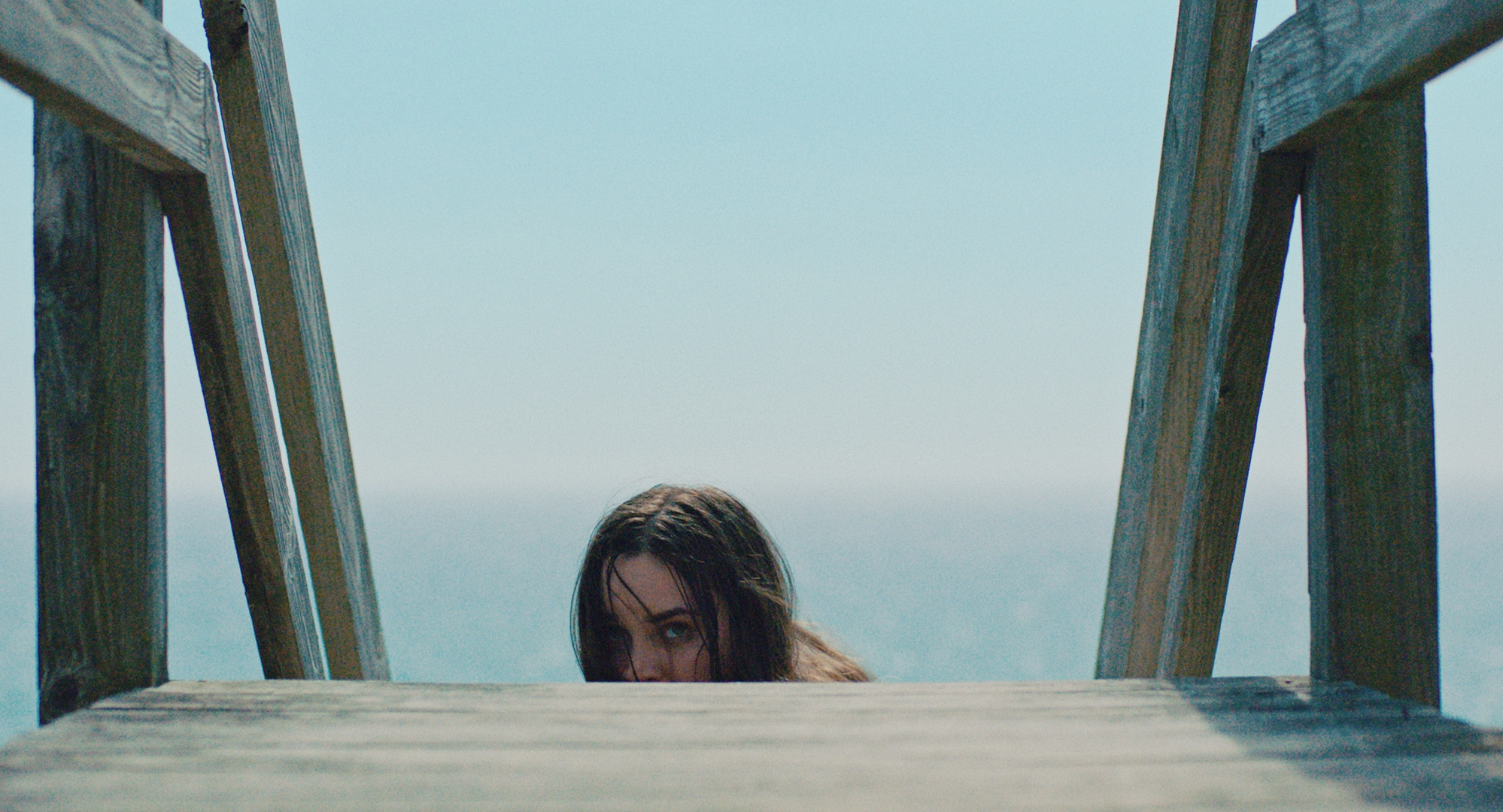

Such an evocation of “the weird” — complete with a first-half/second-half perspective shift — distinguishes Jeffrey A. Brown’s The Beach House, currently streaming on Shudder. Emily (Liana Liberato) and Randall (Noah LeGros) arrive for a weekend at Randall’s father’s beautiful and secluded beachfront home, where they’ll work on relationship issues. (Emily, who studies astrobiology, plans to go to grad school, while Randall wants to drop out of college and chill, postponing any future plans.) But when they arrive they find another vacationing couple, older retirees Mitch and Jane (Jake Weber and Maryann Nagel) for whom — as evidenced by Jane’s frail condition and medicine cabinet full of prescriptions — time is already running out. For nearly the first half of the film, Brown creates exquisite tension from the awkwardnesses within and between these two space-invading couples. A dinner party ends with everyone sharing edibles — probably a bad idea for the heavily-medicated Jane — so that when fluorescent microbes light up the beach and a sinister fog moves in, the characters are already destabilized enough to not fully process what’s about to happen to them.

The Beach House is a deeply disquieting, supremely confident first feature from Brown, a veteran New York location manager who deploys his own knowledge of weird fiction and cosmic horror to craft a tale eerily resonant to the present moment. He sets his subtle relationship story against a world experiencing unexpected shocks from climate change, and where what’s floating through the air can prompt terrifying breakdowns in civil authority. And he’s done all of this on a contained scale that’s a model for inventive low-budget filmmaking. The latter is no surprise, as Brown began his work in locations on two pictures (Kill the Poor and Pieces of April) produced by the now-legendary New York digital production company, InDigEnt.

I began my conversation, conducted over email, with Brown by asking him about those early jobs and how they shaped his filmmaking philosophy. Also discussed: what he learned from directors on the bigger budget films he has worked on, influences ranging from J.G. Ballard to Tangerine Dream, and why he avoided traditional three-point lighting.

Filmmaker: You’ve worked for nearly two decades as a New York location manager, and your first credit on iMDB is 2003’s Pieces of April, which was famously one of the more successful films from the early digital ultra-low-budget production company InDigEnt. You didn’t have scouting credits before that. How did you wind up on that film, and how did that experience shape or influence your work as a location manager going forward but also as a director?

Brown: After interning while I was still in film school (undergrad NYU), I began PAing on independent features pretty much as soon as I graduated. I PA’d on one movie, then the next one the AD was like “now you’re the background PA.” So I did that for a movie, and then the AD hired me again and said “now you’re the Key PA.” I was responsible, showed up on time, and took it seriously, so I moved up quickly.

I was the Key PA on an independent feature that had some production issues (as is very common) and they ended up firing the 1st AD and the line producer became the 1st. As the Key, I worked closely with that line producer, and he liked me and brought me on to “location manage” the shoot of Kill the Poor (another InDigEnt production) in the fall of 2001. It had been largely scouted so I would be more on set, rather than scouting, supposedly. The production designer of Kill the Poor liked working with me at that point as well and he brought me on to Pieces of April.

These InDigEnt shoots were very very small, and locations people are a mercenary bunch. At that time, I think they realized finding an experienced manager was going to be a futile search (all InDigEnt shoots paid $100/day flat in exchange for points), so they were like “this kid seems to be able to deliver, let’s throw him to the wolves.” And man, the wolves were biting.

I think Pieces of April taught me how complex all film productions really are, regardless of budget. April was supposed to be a simple shoot – the story took place over one day, and essentially it was a road trip intercut with action within several apartments in the same building. On the page, very straight-forward. In the end we wound up using three buildings in two boroughs for April’s building, and the road trip took place in New Jersey, Long Island, Rockland County and Bear Mountain. And the shoot itself was only 15 days! Then we shot in the spring of 2002 when it was supposed to be November, so we were avoiding buds on trees, that sort of thing. This super-low-budget movie was actually extremely complicated.

The Beach House was designed to be flexible in terms of adjusting to weather and what-not. The shoot was 18 days. We needed sunny days and got like three or maybe four. Then for any exterior fog, it really needs to be less than 3 mph wind so if we had any windless days, then we would shoot the exterior fog scenes. And the tides are severe in Cape Cod, so our locations team did photo studies of tidal depths. We had to time the scene where Jake Weber’s character walks into the ocean as we had a very short window where the water depth would work for that. Then due to some casting issues we had to shoot totally out of order, which I wanted to avoid. There are some contiguous scenes in the second half of the film that were actually shot weeks apart! But I think when you watch the film, it feels very seamless and simple, which was by design.

Filmmaker: How did you transition out of physical production to make The Beach House? You have an array of independent producers behind your film. Who came on first, and how did you move the script from development into production?

Brown: Locations is not actually a great stepping stone to directing. If you want to direct, you have to direct. Shorts, anything. The more autonomous you can be in the low-budget world though, the better, so having more than one production related skill can be helpful. I think we moved much faster in prep in terms of scouting than if I didn’t have locations experience, but really locations is more parallel to directing, more on track with being a line producer or UPM. Through the years I just had The Beach House in the back of my head and would make mental notes during other production gigs.

Actually, I didn’t ever transition out of physical production. I was extremely fortunate that I had some understanding friends who would throw me scouting work while I was prepping/cutting Beach House. I had to keep working as, you know, you don’t make much money on low-budget movies, even as the writer/director! I think I scouted on like all of the various Marvel shows (Luke Cage, Defenders, DareDevil, etc.) while we were cutting Beach House. Managing is much more taxing on you than scouting, especially in episodic television where you are on-call essentially 24/7. I didn’t manage for a full year while prepping and shooting Beach House.

Our post process on Beach House was easily a year and a half – we had more CG than we’d ever intended so we had to approach those literally one shot at a time. And it was very detailed, subtle work. So in 2018 when we were on these last tweaks, I started managing again. I managed Jim Jarmusch’s The Dead Don’t Die at that time in the Catskills – we should shoot for 12-14 hours, then I would head to the hotel, eat dinner, then review VFX shots for The Beach House for another two to three hours every night.

Sophia Lin was the first producer involved. She was doing another indie film in maybe 2011 and was having an unpleasant time. I think we went out for drinks, and I was like, “We should try to make one of my scripts,” and that was the start of it. Of course, at that point, Beach House was really a collection of ideas and visuals and all within the four characters, one location, horror, [and in a] super-low-budget world. I wrote a few drafts of the script and we shopped it around to some financiers. Trying to get funding based on script alone is pretty much impossible – you really need a short or something more than a script as a proof of concept.

So it really was a long process – after a few years of trying to get funding based on the script, I made the short Sulfuric in 2013 which played at Fantastic Fest, and then we got into IFP with Beach House. That kinda started the process in earnest – Andrew Corkin came on board in the summer of 2016 and we’d secured financing by the fall. I’d write bursts of drafts as well – every few months I’d pump out two to three drafts.

Sophia throughout it all was like, if we are making this for a sub-million dollars, keep it weird. Both Andrew Corkin and our other producer Tyler Davidson (who also came on board in 2016) were very supportive of the scientific concepts in the script and not following the conventional three-act structure. It really was an experimental film in many respects, and I was so fortunate at all the producers believed in that. Corkin has a background in horror, and while Tyler and Sophia’s projects together – Compliance and Take Shelter – aren’t horror per se, with a slight tweak they could easily be horror. That became our pitch really – taking the aesthetic sensibility and intensity of those two films and applying it to a more traditional horror narrative.

Filmmaker: What are some location-selection mistakes you’ve seen directors make that influenced the way you went about writing and then making The Beach House?

Brown: As important as locations can be, 90% of the time in narrative filmmaking, the location is the tail to the actors’ dog – you’re creating an environment for the actors to be comfortable and to be able to get to the truth of the scene. And the “comfort” is both aesthetic and pragmatic: The location doesn’t want to be so wrong that it distracts from the story, and then you don’t want to find a place next to a construction site for a quiet, intimate scene.

If a director is dead set on a location that costs $50,000 and has all sorts of constraints (a hard out, restrictions, etc.), the location manager’s job is to figure out how to make that location work, and then the producer gets to veto it. Sometimes inexperienced producers will put that on the location manager – to drop the ball. That dynamic sucks for everyone – the passive aggressive finger pointing. And the more time wasted in not making decisions can force bad last-minute decisions. As a director I’d ask myself if this is worth the headache. What is this difficult location going to bring to the story?

It’s the “square peg, round hole” aspect of production. The director has a script that he/she wrote without thinking about logistics, and really the script could easily be 10-20 million dollars, but then they get financing for 1 million dollars and aren’t willing to change a page of the “precious” script. It’s not a million dollar story so you end up compromising unwillingly.

In those situations it’s like your hand has five fingers, the glove you want to wear only has space for three. Those two fingers are either going to be surgically removed or we are going to rip them off. And then you have to protect not even the script, but the idea of the script – what is that movie underneath the script that you are trying to make? The better low-budget movies I’d worked on defend that kernel of the idea. Circumstances or budget might change the Met Museum to an art gallery – if the kernel is strong, the story won’t suffer by that change. The scars on the hand won’t be noticeable. They might even be beautiful.

The structure of low-budget filmmaking needs to be flexible – the schedule is made out of taffy or rubber, not crystal. If the director starts making choices that jeopardize the entire production (and no producer is helping those decisions), your little movie can be in trouble. On the low-budget world, there’s no studio to battle with a la Terry Gilliam with Brazil. I’ve worked on so many movies that never come out – they run out of money, then disappear. The producers on low-budget films are really gambling without a net – you read stories about financing with credit cards, second mortgages, that sort of thing. It’s really romantic to go broke on your film — until you go broke on your film.

Filmmaker: You’ve said in other interviews that the script has been in development for almost ten years, during which the science around some of its themes, such as climate change, existential threats to humanity, etc., has marched forward. Could you discuss how you worked on the script during this period in terms of incorporating — or perhaps not incorporating — such science?

Brown: I want to see things in films that I haven’t seen before. I started thinking about Beach House as a science fiction film — exploring concepts like astrobiology and the behavior of microbes and bacteria and life on a subatomic scale. How could I try to incorporate those scientific ideas into a coherent narrative? And what would it look like? The early earth – panspermia, extremophiles. Things like viruses and algae that exist but aren’t exactly alive in some cases. What is that existence like?

I had to kill time in New Orleans in the early stages of writing, so I went to an aquarium and watched jellyfish for like an hour. What would it be like to be a jellyfish? It would suck to step on a jellyfish. Or going swimming in the ocean and seeing a man o’ war floating nearby – the revulsion and pierce of adrenaline of that being close to me. Something totally alien and dangerous but still of our planet.

And really that was when Emily went from being a more trope-like damsel in distress to being an independent, scientific-method focused student. The events in the script are her anxieties. I wanted the film to introduce these scientific ideas in the course of the narrative without relying on a third-act government agency explaining everything. The apocalyptic visions of climate change and new pandemics set against the vacation home and relationship malaise – one of those dreams where the people and places are familiar but re-contextualized to make you uneasy.

The approach is like surrealism in terms of taking two disparate elements and combining them: Bioluminescence is found in water, let’s put it in the air. Water pours out of a faucet like slime. And if, say, The Exorcist’s horrors are rooted in Catholicism, The Beach House is based in evolutionary science, which lined up nicely with cosmic horror – exploring the themes of insignificance in the face of the massive scale of the universe.

When I started reading about evolution and astrobiology and the early earth (books like Robert Hazen’s The Story of Earth, Richard Dawkins’ The Ancestor’s Tale, Christian DeDuve’s Vital Dust, Peter Ward’s A New History of Life, Elizabeth Kolbert’s The Sixth Extinction, etc.), I found that these pop-science books all come at the questions from different scientific fields – biology, geology, genetics, chemistry, climatology, even astrophysics. Astrobiology is a relatively new field that combines all of this – it’s new because until a few decades ago, we couldn’t explore life in the bottom of the ocean or these different scenarios of life on our planet. We didn’t have the technological means to do it.

All of these explorations of deep time, where they start looking at the broadest swaths of life on earth, the geological epochs, that concluding chapter is like “what’s going on with the earth right now is not good for people.” I wanted to weave climate change into the narrative, and it really reflects not just the broader story, but also the intra-personal relationships within the narrative. What would climate change be like to a body? It’s ultimately a form of death, so we are getting into horror. Our own anxieties are borne of climate change, rendering the planet uninhabitable.

I read studies of the surface of the planet Venus, afflicted by runaway greenhouse effect, covered in clouds of sulfuric acid – what would that alien landscape look like, and how could I have characters literally walking through it?

Filmmaker: Your film has a crisp visual style — locked-off camerawork, clean compositions, a lot of, seeming, natural light, and then it moves into a more expressionistic mode as it goes on. Could you discuss how you worked with your DP on the film’s visual schema, and the relationship between budget and the way you conceived of how you’d shoot the film?

Brown: I location managed Jean-Marc Vallee’s film Demolition. He was coming off the one-two punch of Dallas Buyers Club and Wild – like an insane amount of major Oscar nominations between those two films. One of our first days of production on Demolition, our 1st AD, Urs Hirschbiegel, took me aside and pointed at the electric truck, saying, “We won’t use any lights on that truck for the entire shoot.” I didn’t believe him, but of course he was right! Jean-Marc had developed his naturalistic aesthetic with his DP Yves Belanger to favor performance. He literally shot 20-minute takes – the energy of the actors was really his focus, and practical lighting gave him the freedom to shoot 360. I loved the way his films looked.

I’m a big fan of Michael Winterbottom (especially A Summer in Genoa and 24 Hour Party People) and really responded well to Drake Doremus’s Like Crazy – these very naturalistic films. (I watched Like Crazy , Cronenberg’s The Brood, and Antonioni’s Red Desert with the sound off in prep on Beach House.) Some of the smaller films I’d worked on would try to emulate big budget, traditional three-point lighting and they wouldn’t have the time or the crew or the lighting package to really pull that off so you get this mid-level flat lighting that’s overlit – especially night interiors and exteriors. I’m still sensitive to it! It’s like nails on a chalkboard.

I felt that audience’s eyes could accept that naturalistic lighting, and really wanted to resist over-lighting. Even consumer-grade digital cameras can literally see in the dark. It goes back to the design of the film – I wanted to shoot and shoot. It’s my first film so I didn’t want to be in a position where we were always running out of time and we would have to start ripping off our fingers with a bandsaw.

Our director of photography, Owen Levelle, comes from a documentary background. He was recommended to me through our producer Andrew Corkin. His reel had one sequence of a blue dusk that was super saturated and natural – I felt if he did that then he could do much of what I wanted. Then we met and hit it off – I’d been amassing a “recipe” of movies and books and photography and sent him a bunch of stuff. He brought up Mizoguchi’s Ugetsu and Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives; then we went to see Julia Ducournau’s Raw and Dennis Hopper’s Out of the Blue – it was great discussing these movies in the context of The Beach House. We even went to see the drone metal band Sunn O))) play in Queens – they use a lot of fog!

We learned that you have to be careful when you tell producers you want to shoot “naturally” as they immediately think, “Well, then we don’t need lights. Savings!” I’d be careful with that. I’m not a purist (and didn’t take the Dogme 95 Vow of Chastity), but you do need some lights to help with continuity and what not. But it was more like, look, this is what can be done with practical lighting, we can do that as well but instead of shooting domestic dramas, let’s apply that to this weird horror story. It was a marriage of aesthetics and economy in my mind, which I’d always responded to as a filmgoer.

Filmmaker: In many reviews H.P. Lovecraft has been cited as a comparison, particularly with regards to the decentering of the human characters by the changes in the earth. I also thought, a bit, of J.G. Ballard’s disaster novels, in which characters find their psychologies adapting and succumbing to the disasters around them. What particular reference points did you have when conceiving of the film, and why was it important the couple at the center of the film be one whose relationship was stuck in such an uncertain place?

Brown: There was a cool NYRB anthology once called The Colour Out of Space (I think it’s been retitled for reissues) that came out in 2002-2003 that I’d read. It had Lovecraft’s story but also Algernon Blackwood’s “The Willows” and Arthur Machen’s “The White People” (which is totally bizarre and creepy) and described weird tales and cosmic horror. I thought about what modern cosmic horror would be and wanted to write that script. I read some more of it – William Hope Hodgson’s The House on the Borderland was a favorite, and Jeff Vandermeer’s awesome anthology The Weird – and then started looking at how the weird tale evolved through literature. It’s an emphasis on mood and atmosphere – coming from a locations background where I’d spend days just driving around looking for environments to stage movies, I wanted to tell a story where the atmosphere was so severe that it literally consumed the movie.

I’m actually very proud of a sequence in the second half of the film where we see our beach house being taken over by fog – no people. The eye of the camera is coming from a non-human perspective at that point. Much of the movie is about the conflict between interior and exterior environments, both physically and psychologically – outer vs. inner space. The interior takes over after a certain point and things become abstract. I like a lot of darker ambient music – Tangerine Dream’s Zeit, Main’s Hz compilation, Lull’s Cold Summer – and they remove the familiar sonic signposts that you have in more soothing ambient music. The spa or relaxing on the beach becomes unnerving, the sounds are unknown, abstract. I tried to write a movie that felt like those albums, especially in the second half.

I’m a huge J.G. Ballard fan and The Drowned World was a big one for Beach House. Beyond the prescience in terms of climate change/global warming (Ballard was writing in the early ’60s and really greenhouse effect science was around even earlier than that!), there were some passages in the novel where the characters’ thoughts start to regress to reflect the changing environment. The characters devolve. Ballard and other ’60s sci-fi writers like Samuel Delany and Philip K. Dick showed me how they expressed their biographies through their imaginations – when you look at, say, Empire of the Sun and see how Ballard experienced the fragility of Western Civilization first-hand, you see that throughout all of his writing – from the environmental cataclysms to the experimental urban novels of the early ’70s. Cronenberg is similar in that respect in terms of his films being metaphoric or allegorical – I wanted The Beach House to reflect contemporary science and anxiety, which makes Ballard’s fiction that much more remarkable for still being able to be part of the contemporary conversation, 50+ years after it was written.

I did feel that writers and filmmakers like Lovecraft, Cronenberg, Stephen King and even John Carpenter’s influences were so innate in me that I wanted to look to alternate sources and started watching a lot of 1950s science fiction. I read John Wyndham’s Day of the Triffids, which had a plant-like antagonist similar to the pods in Invasion of the Body Snatchers, and I watched all of the Quatermass films. These science-fiction films were dealing with the fallout of atomic radiation as that science-spawned affliction stirred the anxieties of the time. I wanted to approach it similar to the 1950s The Blob – a group of young people come face-to-face with an otherworldly presence, but dressed up in pseudo-mumblecore trappings: Naturalistic lighting, a plotlessness that favors characters’ discussions over narrative mechanisms. And tragedy strikes, turning the characters’ worlds upside down.

I’ve lived through several cataclysmic events in the last two decades – 9/11, Hurricane Sandy, the blackout of 2003. In these moments your personal relationships and consequently your hopes and dreams are put on hold as you deal with what is now immediate in front of you. Writing this during the pandemic it feels like these other tragedies in slow motion, though the speed at which the day-to-day of society froze in 2020 was alarming. Ballard was right again about the fragility of the structures we have constructed as means of life.

In terms of the dynamics of the characters, it goes back to Hermetic saying – “as above, so below.” Emily is struggling with change in her own life before the cataclysm hits. Randall’s idea of the future is not hers, so she will need to adjust to change. And it’s difficult because she’s not lying when she says she loves Randall, it’s that her ideas of love and life are changing. Pretty much every line of dialogue in the movie is a character adjusting to the flux of the world around them. The characters reflect the greater world.

And then the movie itself changes midway through! The two halves of the movie are mirror images of each other – if our overriding metaphor was a reflection of the nature of change in life, then it made sense to me that the film should literally change in front of our eyes. This goes back to being fortunate enough to have producers who were on board with that!

It’s another surrealist thing, the paradox that the only constant in life is change. Consciousness is really our brains comprehending change, even something as ubiquitous as the verb “is” – literally “to be” – that is an expression of change. Time is literally registering change. The movie I feel embraces change, not for the sake of change, but as an acceptance of the world outside ourselves.