Back to selection

Back to selection

Ring in the New: Top Female Filmmakers of IDFA 2020

Radiograph of a Family

Radiograph of a Family As I’ve noted in the past, fulfilling the 5050×2020 Gender Parity Pledge is easy pickings for any nonfiction fest. Within the documentary realm female helmers have long consistently been behind half (and often more) of the highest quality work put out every year anyhow. And this year’s hybrid International Documentary Filmfestival Amsterdam — which like most non-Europeans I experienced exclusively online during varying states of pandemic lockdown over its ample (November 18-December 6) run — proved no exception to the rule.

First there was the wealth of exhilarating new projects by acclaimed veterans to choose from. Czech master Helena Třeštíková screened her latest “time-lapse documentary” Anny, a riveting character study shot between 1996 and 2012, that follows a hardworking bathroom attendant and sometime sex worker (who didn’t start streetwalking until her mid 40s). German avant-garde artist Ulrike Ottinger presented her Berlinale-premiering Paris Calligrammes, an astonishing jazz-infused collage of archival footage, home movies, present-day imagery, classic features and more that meld into a sociopolitical memory piece of Paris in the ’60s (i.e., of Ottinger’s youth). And then there was The Netherlands’ own national treasure Heddy Honigmann, the Peru-born Dutch director debuting her latest slice of cinematic perfection, 100UP. Honigmann’s heart-soaring doc follows seven vibrant active centenarians in Europe and the Americas, including several in New York City. In addition to a not-yet-retired sexologist and a still-attending-university student, Honigmann also showcases famed standup comic “Professor” Irwin Corey who certainly hasn’t hung up his zingers yet. Corey’s thoughts on longevity? “Life is a miracle. Walking on the water was a trick.”

Yet as intoxicating as it is to see these cinematic stateswomen operating at the top of their game it was the films from mostly unfamiliar names that ultimately stayed with me. So after seeing over 40 of IDFA’s mid-length and feature-length selections (so far) here are the handful of female directors I’ll be on the lookout for in 2021. And in the years to come.

Nothing but the Sun, Arami Ullón, Opening Night film.

Though Arami Ullón, who splits her time between Switzerland and her native Paraguay, has been part of her homeland’s film industry since she took a job PA’ing on a TV show at the age of 16, she most certainly wasn’t on my radar until Nothing but the Sun opened this year’s hybrid IDFA. Ullón’s latest is a stunning portrait of one dogged man by the name of Mateo Sobode Chiqueno, who since the ’70s has been on a lonely Sisyphean quest to record (literally, using a cassette recorder) the fast-disappearing culture of his Ayoreo community. Though remnants of the Ayoreo remain uncontacted in the Chaco forests of Paraguay, still worshipping the sun — and this brother’s keeper is fighting desperately for it to stay that way — most are like Sobode Chiqueno, long ago forced off their land and converted to Christianity by dubious do-gooding missionaries.

Respectfully and unintrusively, Ullón follows the indigenous hero on his journey, patiently capturing revelatory conversations and can’t-shake images along the way. Indeed, it’s simply jaw-dropping to watch so many elderly men and women praise Christianity and the “civilized” world they were introduced to when the whites ripped them from their ancestral home. It’s like watching a hostage video. These impoverished folks seem merely to be mouthing practiced words about Jesus showing the way to a glorious afterlife, beliefs presented to them not with love but with threats. Ullón’s camera catches the intelligence in their eyes. They know both what they’re supposed to say and that it’s part and parcel of the bill of goods they’ve been sold. In their hearts they are keenly aware that the old ways presented the true righteous path. How could they not be? As one clear-eyed elder points out, disease and hunger had never been part of their previous forest existence.

A gorgeous sequence of delicately framed dead animals in the sand cuts to a woman describing her father’s death at the hands of the invading whites. And yet though they’ve been colonized by Christians, Mennonites, cattlemen, one after the other, these men and women are forever torn between a longing for the forest and a desire to stay with their grandchildren, who only know the “civilized” way of life. Everything now, including the water, has been claimed by the whites. Everything, of course, except the sun. As Sobode Chiqueno puts it, the Aroyeo are cut trees. Cut trees in a now deforested land. And Ullón’s final image of a forest fire obscuring the sun, equal parts heartbreaking and maddening, serves as the perfect visual testament to the spirit of one powerful film.

This Rain Will Never Stop, Alina Gorlova, IDFA Award for Best First Appearance

Alina Gorlova is actually a name I’ve been keeping an eye out for since I traveled to Kyiv to cover Docudays UA 2018, where Gorlova’s previous film No Obvious Signs nabbed top honors for both the Ukrainian director and her PTSD-suffering lead character — a female veteran of the battle on the border who is denied treatment for her wounds that don’t show. Now Gorlova has turned her lens to another easily dismissed participant in the War in Donbass, Andriy Suleyman, a Red Cross volunteer. What makes Suleyman’s tale all the more unusual is that he actually ended up delivering aid in Ukraine only after fleeing the war in his homeland of Syria.

With a Ukrainian mother and a Kurdish father, Suleyman straddles not just multiple conflicts but also identities — and loyalties. Should he be trekking through daunting snowbanks to help his mother’s countrymen (one of whom earnestly asks why the Kurds are always causing such problems) or back in Syria attending to his father’s (and his) neighbors? It’s a dilemma Gorlova captures in stunning black-and-white imagery and a sound design that goes beyond the predictable bombs to the aural landscape of universal rituals, from unnerving military marches to celebratory Muslim nuptials. And while Gorlova’s mesmerizing artistry is forever on full display not once does it upstage her story. Like the globetrotting protagonist she trails across Europe and the Middle East, Gorlova’s humanitarian impulse always seems to lead the way.

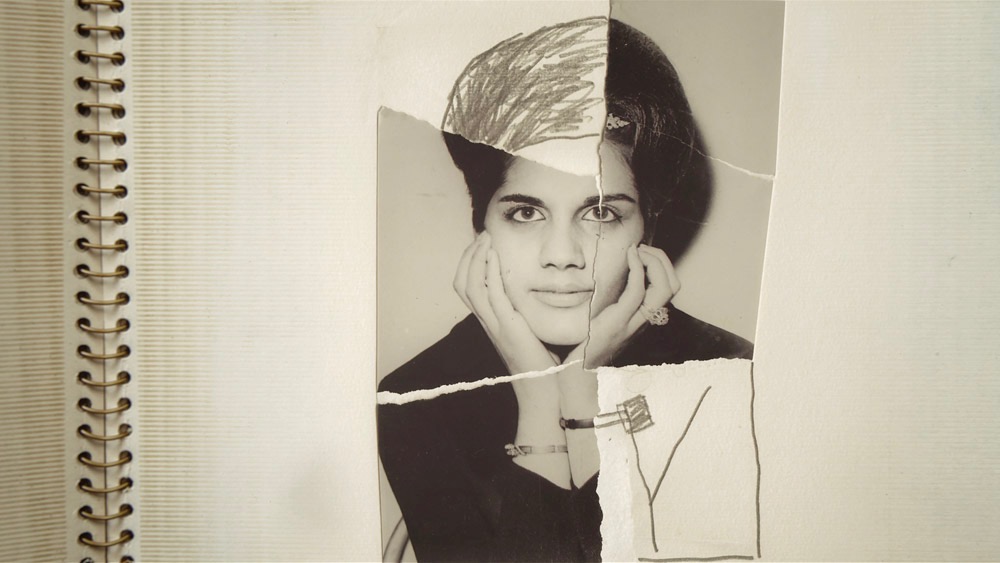

Radiograph of a Family, Firouzeh Khosrovani, IDFA Award for Best Feature-Length Documentary

Though top prize winner Radiograph of a Family, which also nabbed Best Creative Use of Archive, is the fourth film from Firouzeh Khosrovani, it’s the first I’ve seen by this innovative Iranian director (though it certainly won’t be the last). Born in Tehran, Khosrovani was just seven when the 1979 revolution split apart society — and ultimately her own household. With Radiograph of a Family Khosrovani attempts to examine and understand, in the analytical and artistic manner of her secular, music-loving radiologist father, the dashed hopes and dreams of both. To do so she goes back to the beginning, to a time before she was born, when — in a twist that sounds far too strange to be true — her mother married a photo of her father. Too busy with his medical studies in Switzerland to return to Tehran, the wedding had to go on without the groom. And if that doesn’t portend a distant marriage to come I can’t imagine what would.

Through audio made up of letters and reminisces, and imagery culled from home movies and photos, alongside highly composed, still-life shots of the pointedly changing interior of the filmmaker’s childhood home, Khosrovani bread-crumb delivers a time capsule of clues. What happens when a Western culture-embracing progressive lives side by side with a conservative devout Muslim? Whose belief system is upended? Who doubles down? Or does an uneasy stalemate simply ensue? And how enlightened is a husband who coerces his protesting wife into removing her hijab for photos? How feminist is a woman who finally finds her voice in advocating for the policies of an Ayatollah? In the hands of Khosrovani, irreconcilable differences, tensions, and unanswered questions are the ingredients for some revolutionary cinema.

Lost Kids on the Beach, Alina Manolache, Best of Fests

While I’ve long been a fan of post-Ceaușescu cinema Manolache is a filmmaker I’ve unfortunately managed to miss up until now. With her first feature-length project, Lost Kids on the Beach, the Bucharest-based director (and alum of Visions du Réel) trains her camera on the aftermath of her own country’s revolution in a refreshingly novel way. Manolache herself was born in 1990, the year after the fall of the dictatorship, and into a decade that was marked by hope but also by loss. Specifically, a ridiculous amount of lost kids on a beach.

Employing her nation’s celebrated absurdist humor Manolache sets out to find those now grown kids (though they’d never really stayed lost for long) — the ones who dotted her memories of beach vacations, when every summer info on the latest kiddie to be lost or found would be broadcast over seaside speakers. And find them she does, traveling around the country to connect with her post-communist cohort — Romania’s so-called “lost generation” — and to probe each individual’s past, present, and outlook on the future.

“How the hell can you have a revolution and end up worse?” asks one exasperated man who theorizes that the uprising against the Ceaușescu regime was in fact a “coup.” While another former beach kid sees things quite differently. “We get lost, and then we find our way again. In a beautiful manner,” the woman offers. “We lose our way, and when we finally find our place we are happy.” Like much of the Romanian New Wave output, Lost Kids on the Beach’s darkly oddball concept gives way to unexpectedly startling artistic poignancy.

Ziyara, Simone Bitton, Masters

Obviously any filmmaker premiering in the Masters section at IDFA is not a newcomer to the documentary scene. That said, Simone Bitton, whose decades-long body of work has focused primarily on the Middle East and North Africa, is also not exactly a household name (at least not for me, despite the director having won the Special Jury Prize at Sundance for 2004’s Wall). Which has been to my artistic detriment. A citizen of France and Israel, a Moroccan national and an Arab Jew, Bitton is one of those at home in the world filmmakers able to deftly deploy multiple personal vantage points to engage with subjects in a strikingly profound way.

With Ziyara — “a form of pilgrimage to sacred places” — Bitton takes the viewer on a heartbreaking, powerful and visually entrancing road trip. It’s a portrait both of absence and of a relationship that could have been. Specifically, the relationship between Muslims and Jews in Morocco, a neighborly symbiosis that started to erode in the 1950s — when the Jewish population of over 300,000 began its exodus to France, Israel and America — only to abruptly shatter in 1967 after the Six Day War.

Traveling back to her ancestral land, Bitton encounters an otherworldly time capsule, a place devoid of Jews but infused with the spirit and legacy of Judaism. And not by accident but by Muslim design. While capturing the Moroccan landscape with exquisite camerawork, the director visits villages and comes across historic cemeteries, schools and shuls — all lovingly looked after and preserved by the locals who worship a different god. Or do they really? Speaking with these devoted folks Bitton teases out a bigger picture, one that upends the tired narrative of a centuries-old antagonism that cynical leaders of both faiths have been exploiting for nearly that long.

Indeed, it’s nothing less than extraordinary to meet these humble devoted guardians of history and memory, one of whom insists that Muslims and Jews have always been “complementary.” While another describes the two cultures as “cousins” — two peoples intertwined. And as such these graveyard caretakers and synagogue scholars see it as their duty, a calling, to look after holy Jewish objects as they do their very own. As one man puts it, Moroccan Judaism is a “collective heritage.” With the Jews gone the Muslims have lost a part of their “body.” And Bitton for her part has crafted an astonishing cinematic lesson in seeing the “other” as an extension of oneself. Which makes the ending of Ziyara — in a synagogue turned movie theater — all the more apropos.