Back to selection

Back to selection

“Is There Too Much Reading on Screen?” Carey Williams on R#J, Virtual Sundance and Pre-Vis

R#J

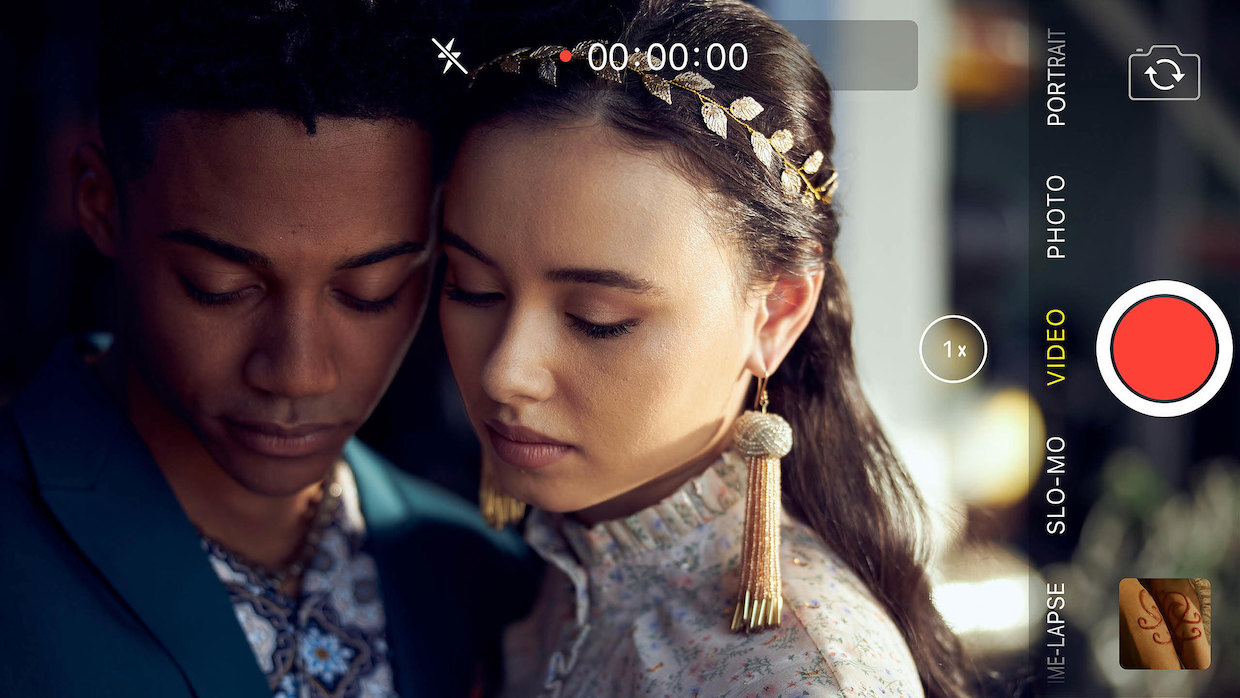

R#J It may still feature two households both alike in dignity, but in Carey Williams’s modern adaptation of William Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, R#J, the modes of communication look decidedly different. Set in California in the here and now, Williams’s film hones in on the title characters’ brief but intense romance via their messaging tool of choice: the smartphone. Back-and-forth texts and DMs, impromptu FaceTiming sessions, tagging each other in Instagram photos and sharing personally curated Spotify playlists add to the cumulative rise and potential fall of literature’s most infamously star-crossed lovers.

Produced by Bazelevs Productions (founded by popular Russian filmmaker Timur Bekmambetov), R#J was conceived as a ScreenLife project, a concept that’s “main idea is that everything that the viewer sees happens on the computer, tablet or smartphone screen. All the events unfold directly on the screen of your device. Instead of a film set — there’s a desktop, instead of a protagonist’s actions — a cursor.” As R#J adheres to this rigorous design, what becomes most impressive about Williams’s ScreenLife attempt is how it expertly displays his keen understanding of modern communication among teens. Isolating and stress-inducing, anxiety-driven and overstimulating, the constant notification alerts on our phone pull our emotions in every which way; for the tragedy of Romeo and Juliet, there’s a sense that these apps are only adding more fuel to the fire of love and despair.

A 25 New Face of Film in 2018, Williams arrived at Sundance last week with R#J, his debut feature, which premiered in the NEXT section of the festival. Before the premiere, I spoke with Williams about the rigorous pre-visualization process, honoring Shakespeare’s text while modernizing the surroundings and the surreal experience of debuting a multi-screen film virtually for all to see (and stream).

Filmmaker: We last spoke two-and-a-half years ago, when you had recently been awarded a prize at the Sundance Film Festival for a short, Emergency. Now you’re returning to the festival with R#J, your first feature. What has life been like for you in the interim?

Williams: In the time since I was at Sundance in 2018, I took some general meetings and did some director-shadowing on a few television series. That was a very interesting experience. I think something was revealed to me around this time though, that I had a better feel for narrative filmmaking as a whole. Working in television is cool and there are a ton of great shows, of course, but it’s so much more about coming in and sticking to something that’s already been set before you’ve arrived. That’s fine and there’s good value in that, but being able to have my voice more readily at the forefront is the thing I most enjoy.

It was around this time that Bazelevs Productions contacted me about making a film with them. R#J turned out to be that project. The idea of casting people of color in these iconic roles (and in this iconic story) was really attractive to me. To have the opportunity to use my platform and my voice to bring this version into the world, all while pushing the boundaries of what I know as a filmmaker and stepping outside of my “traditional filmmaking box,” was worth pursuing. And now here we are at Sundance after working on the film for the past year-and-a-half.

It’s been quite a journey, as I began by rewriting their script and doing a whole pre-vis [pre-visualization] of the film, which consisted of months on the computer and in the edit with my editor, Lam Nguyen. We created the entire look of the movie in a few months, then went and shot it. We spent the better part of last year editing the film, as the pandemic spread and the world was burning down. That’s where the majority of my time went after Emergency premiered at Sundance in 2018—making this feature and exploring the television production world.

Filmmaker: How did Bazelevs Productions initially approach you? Did they strike up a conversation about the ScreenLife format right at the start?

Williams: While there was a script in place by the time they reached out to me [a Romeo & Juliet adaptation], I was very persistent that we couldn’t have any negative stereotypes associated with our characters (nor could they affect the way we went about adapting and modernizing the story). Our initial conversations were about making sure that that wasn’t happening on this film. We also discussed the idea of creating a hybrid between the ScreenLife format and more traditional filmmaking. The film ultimately became a mashup of combining the old and new, from top to bottom. That’s what I was attempting to do, to incorporate traditional filmmaking into a format (ScreenLife) that pushes the boundaries of what film can do. After those conversations, I set off to do some rewriting, some concept shoots and some pre-vis.

Filmmaker: While your film takes place in modern day, the language of the source material was, of course, written in the 16th century, and your script toggles between Shakespeare’s original text and 21st century vernacular. What was that process like?

Williams: I made a few decisions early on, by making clear that we were going to keep the original Shakespearan text for how our characters speak [to one another in person], but that we were going to implement modern vernacular in their text messaging and conversations on social media. Once that was established, it became a balancing act throughout the writing, shooting and even editing. Were the transitions between the Shakespearean language and modern language too jarring? How do we get in and out of each one? Is there too much reading on screen? How is this going to feel to the viewer, to their eyes, and are they getting fatigued by reading all of this on-screen text? There was a lot of trial and error involved. I knew my cast could pull off both versions of the spoken text, I was never worried about that.

Filmmaker: The film features Instagram, Spotify, Twitter, etc., and not a mock version of those apps either, but the actual company names and interfaces. How did you pull that off?

Williams: I’m still convinced they’re going to come for us. [laughs] No but honestly, I’m sure everyone’s done their due diligence in making sure we’re all clear. We wanted to go for that additional realism, as younger viewers are certainly going to recognize the real apps and their designs. For example, we didn’t want to create a fake, madeup service that’s like Twitter but that we can’t actually call Twitter [for legal purposes]. That wouldn’t feel right, so we went for the real thing. We’ll see. I’m pretty sure we’re all good!

Filmmaker: Each social media platform has its own visual specifics that can influence character behavior, right? Like when you send a DM and can see that it’s been read but hasn’t been responded to, that can be crushing! And certain platforms, like Instagram, are big into live-streaming now, which also plays a role in your film. What was the process like of coupling scenes or narrative beats to a certain social media platform?

Williams: We had to take all of that into account. Since film is a visual medium, Instagram did seem to be most readily appropriate, as well as FaceTime calls and live-streaming. What was most interesting for us, though, was how these apps could reveal character. They could tell a story by how we roll them out or how the characters use them in the film. Different apps allow you to do different things storytelling-wise. What’s someone scrolling through on their Instagram? What’s someone reading in a text message? As a storytelling exercise, that was fun to play with. How could we get creative in our character reveals? Within the interfaces of social media apps, we pan over to reveal a message that was sent. It’s visual storytelling via active text messages, which is really cool, I think, and there’s even further to go with it as the format progresses.

Filmmaker: How does one go about mapping all of that out in pre-production? You have multiple screens, multiple direct message chats, multiple web pages presented simultaneously, etc. You mentioned doing pre-vis before the shoot. I imagine it would be incredibly complicated.

Williams: It was an arduous task and I again have to give major props to my editor, Lam Nguyen. He worked incredibly hard putting that pre-vis together and then, in post-production, crafting it in the edit. We scrutinized every little camera move or shift, like, “What does a slight push into this particular word give the audience? What feeling does it evoke? Should we jump in here? Should we not have this here?” We considered a lot in the pre-vis process, shot it, then had to change a lot of it in the edit. We would storyboard scenes out, then shoot them as close to what we thought we were going to need, but a lot of it was thrown out in post.

One thing the pre-vis stage did was inform how we went about rewriting the film. You get some of the pre-vis down, then you watch it back in succession continuously and go, “OK, we need to work on this part. This is not landing.” We’d then go back to the drawing board and rewrite the scene a bit before we went and shot it. Then, as we all say, the edit is another rewrite.

This film was constantly evolving and very much a living, breathing thing right down to the last detail, and I kind of loved that. At some point you want to be done with the film and have to let it go, but it was also beautiful to be able to continue to tweak it and be informed by the world around us. By that, I mean that we were making this film during a pandemic and during the events that transpired involving social justice movements this past summer. Those things creeped into the art and being able to use that was, personally speaking, great therapy for me.

Filmmaker: That pressing social issue aspect to the film feels organic given the story taking place in the present (the live-streaming of an encounter with police, for example). Was that something that stood out to you as you revisited Shakespeare’s original text? This opportunity to modernize the situation while being faithful to the source material?

Williams: Yeah, and regarding that live-stream sequence, we used it as an opportunity to display user comments that are popping up on the screen as the police arrive. There’s a lot going on simultaneously in this film and some you may not even catch. At some point in the film, there’s a little work to be done on the viewer’s part. If you glance at those comments, they reveal commentary on society, yes, but also aspects of character. There’s more going on than just what you are seeing, visually, in some of these scenes. If you were to go back and watch the film again, you might have a very different experience, as you hopefully pick up on other things that you didn’t catch the first time around that enrich the experience.

Filmmaker: I think I know the play fairly well, so when I saw a character in your film have an iPhone with a background image of Radio Raheem in Do the Right Thing, I began thinking, “Okay, so how does that apply to the character’s origins in the Shakespeare text?”

Williams: I had to go back and revisit the original play, because I couldn’t recall when I would have originally read it. I remember seeing the Baz Luhrmann film adaptation from 1996, which I thought was incredible and obviously possessed quite a vision. But I had to go back and reread the play before embarking on this project. It was entertaining in its play on words and its use of innuendos and things of that nature. I wanted to incorporate that into the film and inform some of the commentary we have. It’s very rich for exploration!

Filmmaker: The setting is extremely important to this story, in any context or modern retelling. While there is a Verona in California, I believe you shot in Los Angeles right before the pandemic shut everything down. How did you secure some of your exterior locations?

Williams: While we did shoot in L.A., we were originally planning on shooting in Louisiana (within the New Orleans area), but then we shifted to making it a more L.A.-specific story and scouted from there. The location-scouting was typical enough. We visited different areas and neighborhoods that I felt spoke to the different environments our Capulets or Montagues would find themselves inhabiting. There was actually a whole scene that didn’t make the final cut where you would see the contrast between the Capulets’ homes and the Montagues’. We never had to steal locations or anything like that. We had complete control over the areas we were shooting in.

I originally had this concept in my head where everything in the film was going to unfold in real time, live as it happens. For example, an actor who was in the subsequent scene would need to physically be nearby and ready [for their cue] and the film would unfold like an actual play. However, after much consideration, we eventually decided not to go that route, ending up filming different takes and moving things around in the edit. As a result, the cast didn’t have to be at the ready at so-and-so location, waiting for their cue. But our locations were chosen with the belief that we would be shooting the entire film in real time, so we found areas where the actors could be close to one another. We got creative in finding spots that could play as two or three different locations on our modest budget. I’m used to having to turn one location into numerous locations very quickly. When I walk into a place, I’ll often go, “OK, if we look in this direction, this location can be this with this way, etc. etc.” I enjoy that process. It allows us to move fast on our limited schedule, as we eliminate the need to move around to a bunch of different locations. Oftentimes, the viewer will never spot it and the production team are game to flip a location into something else. That’s part of the fun of being creative! Even though the film is a L.A. story, I didn’t want it to feel too L.A. I wanted it to feel like its own thing, like, “yeah, it’s still L.A. but it’s not that L.A., with all of these L.A. landmarks,” or anything like that.

Filmmaker: After production wrapped, the pandemic subsequently shut everything down. Was your post-production experience a virtual one?

Williams: Lam and I were working in an office for a few weeks right before everything shut down. Once the pandemic hit, we did the rest of the film remotely. We socially distanced ourselves from each other but were still able to spend the next few months finishing the film.

Filmmaker: And how do you feel about the film having its world premiere in a virtual setting at Sundance? I imagine it’s almost apropos, given the film is so in tune with how we use modern technological devices. Hopefully viewers won’t be on their smartphones scrolling through social media as they watch, however…

Williams: It does seem fitting, right? The nature of what this film is, what it looks like, having people stream it from their home feels very much connected. That’s not lost on me and I hope that, whatever viewers may think of the film, the work gets out there and resonates with people, especially young people. That’s how they experience a lot of their media, through tablets or on their phone or watching something at home on their computer. Don’t get me wrong, I think there’s a lot of value in having a film play in theaters, of course. People still love to go out to see a movie, for that experience of “we’re going out, we’re going to sit in a theater with a bunch of other people and enjoy a film together as a communal experience.” But I feel like specifically with the pandemic still ongoing, Sundance has worked really hard to create a communal experience that, while virtual, is still replicating the theatrical experience the best they can.

There are these virtual hubs at Sundance this year where people can (virtually) walk into different spaces and rooms with their avatar and talk to one another after a screening. It’s replicating the [in-person] festival experience! As everything in the world is rapidly changing, we’re all trying to figure things out. The beautiful thing to come out of all this is that we’re still able to create and share our art. As long as we can continue that, it isn’t that crazy to hear, “Well, your film is going to premiere via streaming.” People will still have their own experiences watching the film and will still be moved by it, whether it’s viewed in a theater or at home. The safest thing to do right now is to stay at home, and that’s fine. As long as we can still share the work, I’m thankful.