Back to selection

Back to selection

Render Time: Director Penny Lane Talks with A Glitch in the Matrix Director Rodney Ascher about His Reality-Questioning Documentary

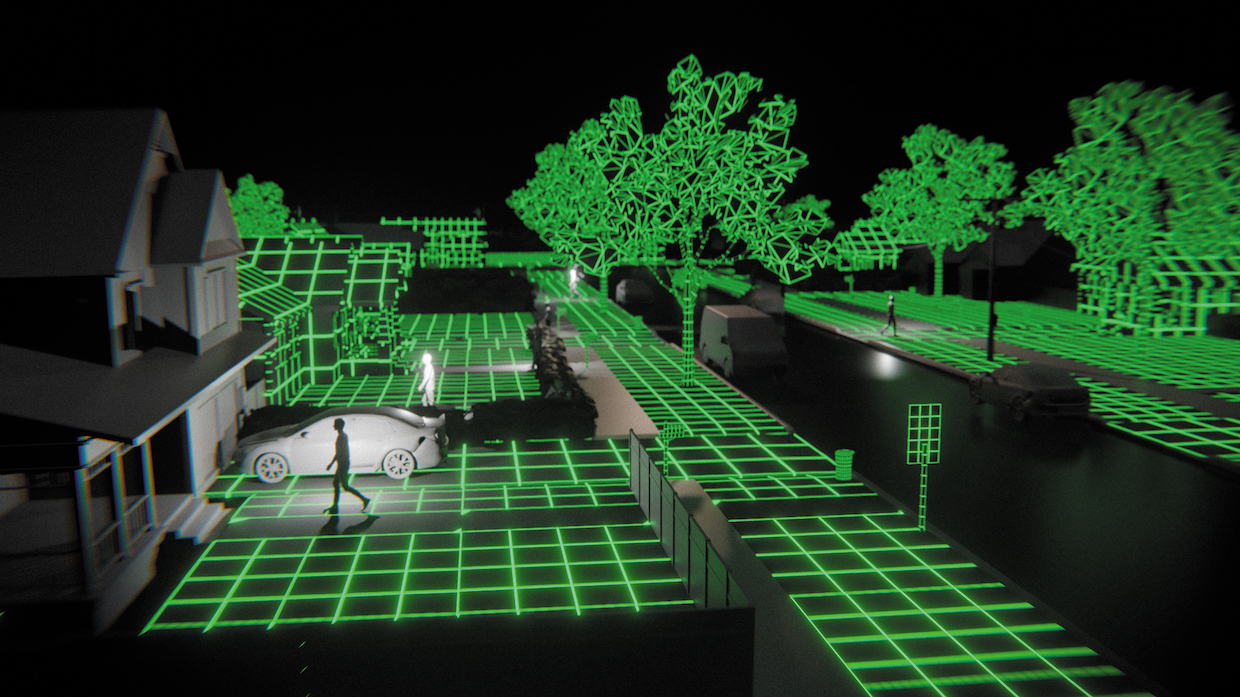

A Glitch in the Matrix (courtesy of Magnolia Pictures)

A Glitch in the Matrix (courtesy of Magnolia Pictures) In 1977, a characteristically fervid Philip K. Dick arrived to lecture at a science fiction convention and share his experiences from three years earlier, when he became convinced that the world was a simulation, one of many (“there may be 30 or 3,000 of them”) operating simultaneously, glimpses of which he’d seen. Clips from this speech (“If You Find This World Bad, You Should See Some of the Others”) and the Q&A that followed frame Rodney Ascher’s A Glitch in the Matrix. In the five-chapter (plus an epilogue) dive into the world of “simulation theory,” Ascher focuses on five subjects as he did in Room 237. In that film, they were united by possessing idiosyncratic, elaborate and often deranged theories about The Shining. In Glitch, four of the subjects are convinced to varying extents that they’re living in a simulation. After watching The Matrix hundreds of time, the fifth, Joshua Cooke, acted on his doubts that his own family was real and went much further.

Ascher’s first four subjects are passionate in their convictions, generous with their time and prone to humanizing digressions. Their Skype interviews serve as the basis for animated renderings of each subject, which works neatly as a formal choice: If people have no true form, any external avatar will do. The results are comically grotesque, close to the delirium of The Fifth Element’s elaborate array of alien life forms, and their stories are rendered using around a half-dozen vivid animation styles. One subject, Paul Gude, describes realizing nothing around him was real during a church service. Surrounded by unnerving white human forms, the oppressively rendered building begins dissolving down to its wireframe form, a move into the realm of The Lawnmower Man or The Thirteenth Floor (one of the many films from which a clip is inserted for illustrative purposes—this is the Los Angeles Plays Itself of simulation theory). Speaking from prison (he’ll be eligible for release in 2042), Cooke is only heard over a scratchy phone connection, his chilling story recreated in a depopulated suburban house plunged into noir chiaroscuro. Ascher isn’t here to look down on any of his subjects, despite supplementing their true believer testimonies with interviews of more skeptical outsiders, including Dick scholar Erik Davis and philosopher Nick Bostrom, whose 2003 paper, “Are You Living in a Computer Simulation?” turbocharged serious interest in these ideas. (Bostrom and Davis appear in Glitch as their unanimated selves, establishing another formal divide.)

In his speech, Dick said, “In the alternate world that I remembered, the civil rights movement, the antiwar movement of the ’60s had failed. And, evidently, in the mid-’70s, Nixon was not removed from power.” That idea formed the basis for Dick’s novel Flow My Tears, the Policeman Said, in which Nixon is remembered decades on “as the Second Only Begotten Son of God.” “It is evident from this and many other clues that Flow My Tears deals not with our future, but the future of a present world alternate to our own,” Dick concluded. “It was dreadful; we overthrew it, just as we overthrew the Nixon tyranny, but it was far more cruel, incredibly so, and there was a great battle and loss of life.” Political trauma prompting such wishful hypothesizing makes sense; the Trump presidency was another particularly aggravated case of “the algorithm’s gone wonky.” At one point, Ascher cuts a montage of TV talking heads into 32 people simultaneously proclaiming in split-screen, “This is extremely dangerous to our democracy!” If you’re not willing to believe that inadvertently unified Greek chorus can be accounted for by the power of clichés proliferating themselves, a more extreme explanation can start to seem reasonable, or at least understandably tempting.

To speak with Ascher, we asked Penny Lane, a filmmaker whose own body of work includes the all-archival Our Nixon as well as The Pain of Others, assembled from the YouTube vlogs of three women convinced they have Morgellons disease, a condition that’s variously been described as “controversial,” “cryptic” and “scientifically unsubstantiated.” After its premiere at Sundance 2021, A Glitch in the Matrix is out from Magnolia Pictures on February 5. —Vadim Rizov

Filmmaker: I was thinking about how I would describe the three films of yours that I’ve seen. For me, they’re all about the problems of the human mind, in some cases dealing with the fine line between genius and madness or, in the case of A Glitch in the Matrix, the fine line between enlightenment and madness. Tell me what you think about this description.

Ascher: I like it. I don’t know if I’ve ever heard it expressed like that. I mean, I kind of look at these movies as being about people trying to make sense of the world [at] different scales of magnification, whether they’re trying to understand a piece of art, their dreams and the supernatural or, in this case, the world around them. Certainly, lots of people on the internet who feel like picking on the movies or the characters may call them crazy. I wouldn’t, although you do have [in the film] people like Philip K. Dick, who was falling into his own rabbit hole, or Joshua Cooke, who—after the fact—was diagnosed as having mental illness.

But where you [define] that line is very tricky. I typically think, even when I don’t agree with folks, that they make sense in their own ways. I also don’t necessarily think I’m the only person working in this territory. I mean, in your case, I think about The Pain of Others. And certainly, Errol Morris—Tabloid comes to mind or even his portraits of [Donald] Rumsfeld and some of those figures.

Filmmaker: Some of the books I’ve been reading recently have been memoirs of people living with schizophrenia, and I’ve also been reading a lot about the history of skepticism in philosophy. Some of these ideas that are in your film were in both of my reading sets, so it was really exciting for me. I’ll share with you the one part that I laughed the loudest at. Really close to the end, Nick Bostrom says something like, “Maybe we have figured out six of the 10 things we have to know to know what’s going on [with our existence].” I laughed so hard because I think we have figured out negative six of those things!

Ascher: You think he’s a little overconfident?

Filmmaker: Yeah, but then he does go on to say, maybe the four things we don’t know are so monumental that the six things we do know would be completely changed anyway. So, it’s not like he’s that overconfident.

Ascher: Well, you know, he’s considered kind of the guru of [simulation theory], but even if you take his three-pronged hypothesis, the notion that we’re in a simulation is only one of them. And who knows if the three slices of the ideas [contained in his hypothesis] are equal size? There’s a moment in Room 237 when [WWII historian] Geoffrey Cox talks about not only the death of the author but sort of hedges his bets about his own theories about the movie and qualifies them as only one possibility. I know there’s a version of [this film] where those qualifiers aren’t left in, where it’s more interesting for [the audience] for [the subjects] to be 100 percent [convinced] by these ideas. But one thing I really try to do is reflect the feelings and ideas of these people, whether or not they look at things differently than I do or how I expect the audience to. I am trying to put the audience in the heads of people who look at the world differently than they do and try to help them see the world through those eyes.

Filmmaker: You have two sets of interviews in the film. One set of interviewees you called “expert testimony” in the credits. The other set of interviews were with people that you referred to as eyewitnesses. Can you talk about the difference between those two and how you worked with that difference in the film?

Ascher: It was something that evolved over the course of [the filmmaking]. In the other two films, I think everybody would’ve been eyewitnesses, and I have typically shied away from calling people experts. But in 237 we never talked to anybody who worked on The Shining. It’s all about the audience reaction. And in The Nightmare, we never talked to any psychologists or sleep experts. It’s all just people who are going through this [experience] and the way they make sense of it. That was sort of my intent going into this one, but when we were able to get Nick Bostrom—and he clearly wasn’t all in on the fact that we’re in a simulation, that it was only a possibility—it felt like treating him like the other people [in the film] didn’t quite make sense. And the same thing with people like Erik Davis and folks whose perception was a little more distant. What was interesting about the four [witnesses]—five, if you count Joshua—is that most of them had these conversion experiences, these revelations, or went through a strange period of their lives and upon reflection decided that [simulation theory] was the explanation that made the most sense.

As I spoke to other people who didn’t necessarily share that feeling, they still brought enough to the story that I wanted to include them. And because I overthink how these things look, I said, “Well, I can’t visually treat them exactly the same if they’re performing a different function in the film.” It was pretty early on when I had decided to replace the interview subjects with animated characters. Then I was just like, should we do the same thing with these other folks [the experts]? Ultimately, we decided on a sort of re-photography look. We took the Skype interviews and experimented with all these different kinds of high-definition monitors. Most of them, when you film [off the screen], are, for lack of better words, gross and ugly.

But I had one friend who had this ancient, first-generation HDTV, which weighed two-and-a half tons and was as thick as it was wide, and it had a high-definition Trinitron screen. And when we re-photographed the interviews on that, it almost looked like the videophones that you saw in ’90s cyberpunk movies, like Blade Runner or The Lawnmower Man. And that felt like an interesting way of differentiating [between the two sets of interviewees]. We’ve got the characters who believe that we’re in a simulation, and we’re looking into cyberspace and seeing them looking out at us, so they’re animated. But these [experts] are folks who are reporting back to us from a level outside, so we’re looking through the other side of the screen.

What’s funny is that there are a couple of characters who didn’t neatly fit into either slot, like Jeremy, whose Reddit screenname is “I am a non-player character.” For him, we went with blurring his eyes to kind of evoke the anonymity of Reddit. And Joshua—arguably, we could’ve made some fake prison background and put an animated character in there. But I think the fact that we were only able to talk to him on the phone was part of the story. And since he no longer believes that stuff, it was a question: Is he an eyewitness? Is this expert testimony? We kept trying to separate them into those two categories, but nobody fits into any square boxes.

Filmmaker: How did you find your eyewitnesses?

Ascher: Most people found us. When we decided that we were going to make the movie, we made an announcement, and a couple of blogs wrote about it. We set up a Facebook group, a Google Doc and an email outreach. We had a long list of people who sent us their stories, then I probably interviewed 20 of them for the four that we chose. If I’m not wrong, everyone who is an “expert witness” is someone we reached out to, based on something that they had written or done previously.

Filmmaker: What was the outreach? Did you say, “Do you believe we live in a simulation? Have you had any experiences that suggest that?”

Ascher: The big one was an article on Boing Boing. I know one of the editors, and he wrote an article that I’m starting this project—if you believe that we’re in a simulation and you want to appear, and you have a story to tell, follow this link. The Nightmare was similar: Half the people were folks that found us, and the other half were people that we found. The irony is that after the film comes out, the number of people who reach out to you increases exponentially.

Filmmaker: Then, you have to explain to people that you’re not in the business of doing sequels to your own documentaries.

Ascher: And do a little bit of therapy, after care. “You’re not crazy. A lot of people feel the way you do. Thank you for sharing your story.”

Filmmaker: Maybe it’s just because of who I am, but I think I put a lot of stock in experts. So, I’m like, “Oh, this is Nick Bostrom. He’s a very important person. He must know what he’s talking about.” It sort of doesn’t reflect well on me, but I know that that’s part of what happens in my psychology with expert testimony. I think it works really well [in your film]—it gave me enough back and forth between the part of my brain that’s very engaged in philosophy and the part of my brain that wants to understand these people and their experiences in the world. But I also loved your characters, your eyewitnesses. I was amazed at how connected I felt to them as humans, despite the fact that you dressed them up in these avatars. I assume you did that in post—that you did interviews and then animated them? Or did they create their own avatars and then you did the interviews while they were in their avatars, if that makes sense?

Ascher: At one point, we were exploring the idea of using a real-time Instagram Snapchat kind of animation filter. But we interviewed many more people than made it into the final edit, and we didn’t want to go through the time and trouble and money of designing animation avatars for characters who didn’t make the film. I engaged this comic book artist, Chris Burnham, who’s done some really wonderful, fantastical Batman comics with Grant Morrison, Batman Incorporated. He has a really great knack for costume design and character design. He drew multiple sketches and refined and came up with each of those avatars as drawings. I let him watch a rough cut of the film, so he had a sense of both what the people looked like, but also their personalities and what kind of things were going to happen to them. And then—I was going to say the 3D team, but that’s going to give you like the misconception that it’s an ILM production where there was a cubicle farm.

Filmmaker: No, I looked at your animation credits. I’m a very savvy viewer. There weren’t that many names.

Ascher: There were a handful of guys working in their apartments, Skyping with one another and having long chats. One guy would take the drawings and use them to design a 3D character, then another would do the animation and so on. But it all started with Chris interpreting those characters. It took a while to figure out what they were going to look like. In early stages, I thought maybe we would have different illustrators do each different character to make them feel more unique. But it seemed to make sense that these are radically different characters, but maybe it’s like they’re playing the same videogame, like they’re all Fortnite characters.

Filmmaker: That’s what it felt like to me. As a person who doesn’t play any of these games, I kind of didn’t know if they were from World of Warcraft or something. It felt like they were consistent, and they were in a certain world together.

Ascher: My son plays a lot of those games; in particular, Fortnite, where you can play with all your friends and do the combat, the survival game. But it also has social spaces where [players] can just hang out. Seeing fifth graders who look like these seven-foot tall cybernetic warriors talk about homework and snacks is kind of awesome but also very trippy. Especially during COVID, when kids have been so isolated, the games are not just an activity but a place to hang out.

Once it started to come together, the guy who animated it, Lorenzo Fonda, wore one of those rubber scuba mocap suits—now we’re at the place where movies at this budget level can do that sort of thing; you don’t have to be Avatar. He can sit alone in his apartment, while connected to a laptop and watch the original interview, then kind of mimic it. It wasn’t animated with a mouse, it was animated with a body. And I think [the characters] feel very organic that way. But you also get that feeling in a Warner Bros. cartoon, where the coyote and the sheepdog clock in and out. These are more like the moments when those characters are in the break room. They’re talking about their mortgages and marriages. It’s not the scene where they’re inhabiting their roles. These [scenes] are those characters’ days off.

Filmmaker: I work with a lot of found footage, where you, or at least I’m speaking for myself, have to have rules that you set for yourself. For this particular project, did a set of rules emerge regarding what sort of images would fit in your palette? Or did you feel like anything goes?

Ascher: As these things come together I start with an “anything goes” attitude, then progressively narrow it down to a few buckets that feel on-theme and don’t clash with the style of the film. For this one, anything based on a Philip K Dick story seemed apropos, and an adage he coined was also hugely inspiring. In VALIS (his fictionalization of that revelatory 1974 experience we talk about in the film) he wrote, “The symbols of the divine initially show up at the trash stratum.” I just love that. I think in the context of the scene he meant candy wrappers, newspaper scraps, etc., but I think it’s even more relevant if you’re talking about cultural trash: comic books, dated genre movies, TV commercials, paperback science fiction novels (like the kind he wrote), so that opened up it up to a lot of images I found apt and often quite beautiful, even if they came from movies that haven’t always aged well. All sorts of interesting coincidences starting popping up while using that stuff, one small one being Keanu Reeves’s appearances from The Matrix and Johnny Mnemonic but also Richard Linklater’s Dick adaptation A Scanner Darkly starting to bleed together. YouTube footage also quickly became indispensable considering the amount of time we spend talking about video games but also the way popular performers become our virtual friends, spreading across millions of screens. Brian Oblivion would have loved it.

Filmmaker: Were the 3D animations mostly created in a game environment, or were those mostly created by your design team from scratch?

Ascher: They were mostly from the design team. Here, I’m going to have to shout out Ross Dinerstein, our producer, for giving us this flexibility. When we started this movie, we didn’t know what the story was or what it was going to look like and settled on a budget that felt responsible for a project of this scale. Then, we figured out how we were going to spend it as we worked.

At one point, I thought maybe it’d be fun to shoot it on a backlot and have one animated character be surrounded by extras working as the other characters. In the end, the bulk of it was created in fairly conventional 3D programs, but part of the fun of it was getting into ready-mades. There are these sites where people upload their own characters, their own designs. Like, you can say, “I need a model of a car, and I want it for free, or I want it for $5, or I want the $500 top-of-the-line car, where everything inside is modeled and can move.” Then, you get all of these semi-pro uploads to choose from. The car that Paul’s dad is driving is something that we found that way. I was hoping that we could show the process of a pull-down menu and of choosing these things within the film itself. The same thing with casting. All of the avatars were custom made, but all those [other] characters, the sort of extras, were all—what’s the word in fashion?—“off the rack.” You can just drag down the menu and say, “OK, I want an adult male, fat,” and there’s 50 to choose from.

Scrolling through those windows is kind of uncanny because the people move a little bit. It’s kind of like visiting an animal shelter, as each one is hoping to catch your eye and to get collected. That also kind of ties into the whole NPC [non-player character] discussion of characters who aren’t fully sentient. There’s that one shot from Blue Velvet, where there’s a guy walking the little dog. Meditating on NPCs, we think of them more as extras, both how they appear as characters within movies but also how when you’re shooting, extras typically get sent to a different catering truck than the principals, and the film crew is not as respectful of them as they are of the main characters. There’s sort of a powerful free-floating metaphor around NPCs, and it’s kind of a depressing one. So, early on, we talked about the idea of NPCs and making them [less well-defined]. It’s also a way of working with limitations. I think the animation looks pretty good, and these [animators] are incredibly talented, but this was never going to look like a Pixar movie. Simplicity is part of the vocabulary.

Filmmaker: I loved the recreations. I will never forget the image inside the church of the meat bodies. I just lost my mind. I could tell that you didn’t have the biggest budget in the world, but you used it so wisely because it felt so coherent, so beautiful and so interesting. OK, one final question. I was struck by the heavy religious overtones in the film and the topics that are being discussed. What does it all mean? What’s the point of life? These questions have been at the heart of religion from the beginning. I found myself wondering with particular people in your film at particular moments, how much of this is a search for God or a sort of yearning for heaven? How much do you feel that some people take the ideas of simulation theory and create a kind of religious frame around it?

Ascher: The religious aspect of it—that talking to these people about simulation theory almost always seemed to get into religious questions—was kind of a surprise to me. There are folks like Erik Davis in the movie, who talks about its similarity to older religious ideas. But even Jesse, the guy who talks about playing videogames, has some really striking comparisons between videogame life and our [everyday] life and is imagining a religion of the future based around this. It could be that we’re one charismatic guru away from that happening.

In the wake of 237, I was thinking a lot about conspiracy theory. I didn’t coin this idea, but it’s something that has resonated with me—it’s reassuring to think that someone’s in charge, whether or not you agree with them or know their motives, rather than thinking the whole world is just a random series of chemical reactions. And clearly, simulation theory falls into that world, too.

Filmmaker: I thought about that when somebody in the film said something about “the player.” And I was like, “Of course, to have a simulation, you have to have a player, someone who’s creating this.”

Ascher: There is a god.

Filmmaker: Right. Unless you think the simulation is itself just emerging out of atoms colliding in some way that we can’t understand. I love when one of your characters talks about how he tries to play the game in a way that keeps the player interested. I have to keep the player interested in me, so sometimes I do crazy things just to mix it up! Which is, by the way, how I deal with life as an atheist. I feel like you have to do something that fucks with the fabric of reality around you, or else you do feel like you’re stuck in a game that you’re just kind of moving through the levels of, you know? So, I related to that very much. But I don’t have the idea of a player who’s a puppeteer behind me who might get bored if I don’t do interesting things.

Ascher: Well, the idea of the player is so strange. Like, are you not the player? Years ago, for the purpose of a story that I never wrote, I was trying to come up with the idea of a religion for some cult to believe in. It wasn’t the metaphor of the game so much, but of the author, in imagining a world where how different the clergy would be if they sat us all inside of a grand narrative. If you went to a priest or a rabbi asking for advice, what they would tell you wouldn’t be what would be good or what would be stable, it’d be, “Well, what’s the most interesting thing for you to do?”

Filmmaker: What makes the best story?

Ascher: “You should totally kill your boss. I totally recommend murdering your boss.”

Filmmaker: “No one’s going to buy this book if you don’t do something!”

Ascher: Exactly. You know, I think the other videogame idea about the world that resonates with me is breaking out of your [repetitions]. If you’re at Disneyland, you can’t just ride the saucers again and again and again and again. There’[re] all of these other attractions that you should try to check out.

Filmmaker: The stoics had a lot to say about how to live once you’ve realized that nothing really means anything. I loved that one of your subjects says how [his uncle asked], if we’re in a simulation, what’s going to keep you from shooting [someone] in the head? And then he says, “Well, is that what you want?” People think that without religion, everything will just fall to pieces. People will just be raping everybody. I don’t think that’s what everyone’s dying to do. I’ve always found those arguments so cuckoo, you know? If somebody wants to go on a shooting rampage, the existence of god or a simulation, none of that’s going to make any difference in that equation.

Ascher: Well, it’s so scary what he says [about shooting your uncle]—the notion that that’s the only thing holding you back. Another character talks about the dangers of people thinking that there are no consequences, and how then there’s going to be [life as a game of] Grand Theft Auto. One thing I’m concerned about is that people see this as an attack on videogames. It’s more that if [we think we’re in] a game like GTA, things could get pretty hairy. In a game like GTA, the entire universe is built to encourage you to commit acts of mayhem. And Fortnite is built for everyone to fight to the death. So, that raises the question of, well, what is this world built for?

Filmmaker: I think that’s actually where your film lands, right? What is this world built for? That is the feeling that it left me with, as well as this idea of what it means to love. And to use your meat puppet wisely. I think that’s all I wanted to talk to you about it. I’m happy to meet you, and I’m going to think so much now about what this world was built for. It’s a really great question.