Back to selection

Back to selection

Shutter Angles

Conversations with DPs, directors and below-the-line crew by Matt Mulcahey

“We Had to Come Up with Whole New Protocols”: DP Jeremy Mackie on Making Zoom-Recorded Pandemic Film Language Lessons

Mark Duplass and Natalie Morales in Language Lessons

Mark Duplass and Natalie Morales in Language Lessons On a microbudget feature with a skeleton crew, you often end up wearing multiple hats. But a different metaphor is required to describe cinematographer Jeremy Mackie’s contribution to Language Lessons. It’s more like Mackie made the hats from scratch, then mailed them to the actors with instructions on how to wear them.

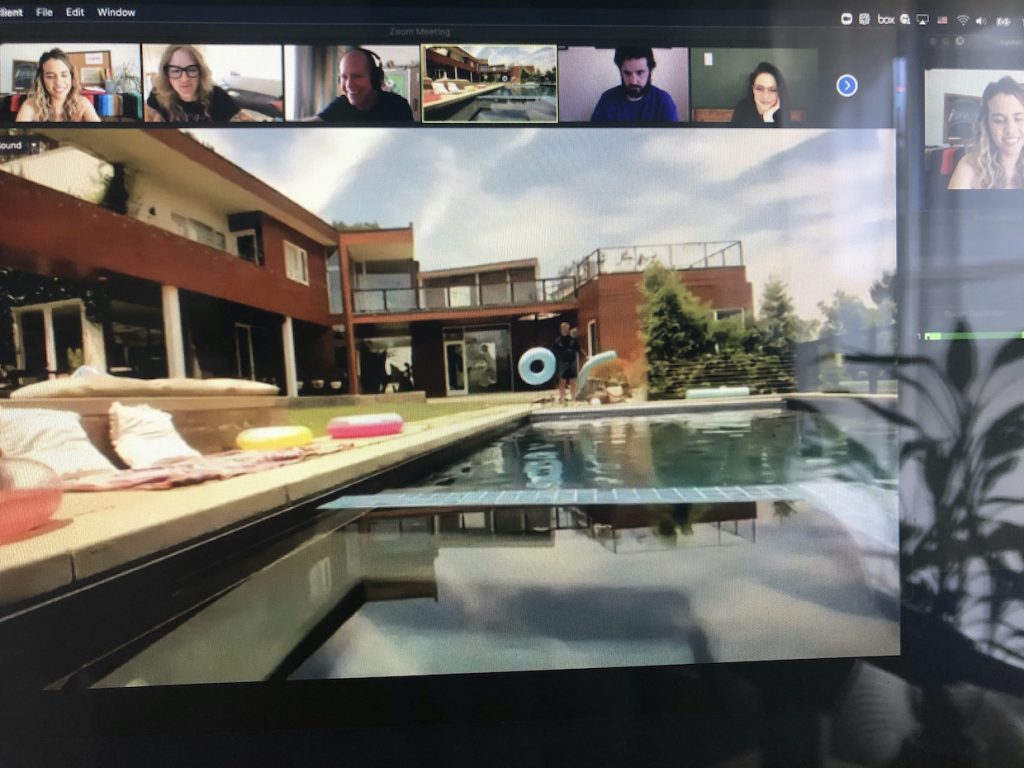

The film stars Mark Duplass as a grieving Angeleno who platonically bonds with his Costa Rican tutor (Natalie Morales, who also directed) via Zoom during weekly Spanish immersion lessons. Though the movie—which debuted at this year’s Berlin International Film Festival before playing South by Southwest—never mentions Covid, it’s a production born of the pandemic. Shot over eight days last June, Language Lessons was made almost entirely remotely, recorded via Zoom with rigs Mackie created by affixing laptops, lights, microphones and webcams to kitchen cutting boards and then sending them off to the actors.

With the film in select theaters now, Mackie talked to Filmmaker about No Kino Fridays, the difficulty of bumping up a position and how Language Lessons was “like sending movie astronauts into space.”

Filmmaker: The bio on your website opens with your time as a theater projectionist in college. What was so formative about that experience?

Mackie: I worked at the Varsity [in Seattle] in the University District. It was the first job that I picked for no other reason than I wanted to be there. I think that’s also why I chose to work in the film industry, because there’s no good reason to be in the film industry except that you want to be there. Everything else doesn’t really add up. (laughs) At the Varsity one of the projectionists took me under his wing and taught me how to load a 35mm projector. I remember projecting Two Lane Blacktop when I was in college. It’s a very existentialist movie. I was trying to pay attention to the movie while watching the projector at the same time. At the end of that movie—spoiler alert—the film burns. There was this moment where I thought the film was actually on fire. All through college I worked there as my side gig—got to see a lot of great movies, got to handle film. The movie theater was a very magical place for me.

Filmmaker: I toured a projection booth in Indiana a few years ago that still had a 35mm projector and the booth had a “panic room” for the projectionist to hide in if the film caught on fire.

Mackie: I didn’t have one of those, but some of the booths I worked in were fireproof in case there was a fire from the nitrate film. The Egyptian in Seattle was that way. It had these beautiful old 35mm and 70mm Norelco projectors.

Filmmaker: Did you have a favorite theater as a kid?

Mackie: I grew up in a one-theater town, a very small town in Eastern Washington over the mountains from Seattle called Omak. The town had 5,000 people then…and it still has 5,000 people. (laughs) They do have three movie screens now—they got a small multiplex. When I was growing up, that theater would get movies months after their release. You would see the trailers on TV, then they would [arrive in our theater] three or four months later. They would play usually late-run popular movies, basically whatever they could get that was the biggest draw. There wasn’t really much arthouse programming, but the theater owner did try to slip in a few things occasionally. One of the first movies I remember seeing there was Time Bandits at a very young age. My parents didn’t have cable growing up, so the VHS store was huge to me in that era when Pulp Fiction and independent films really started to open up.

Filmmaker: You began working in film on the G&E side of things, ultimately gaffing a lot of movies with Mark Duplass and also Lynn Shelton. What drew you to that department?

Mackie: Out of film school, I was just looking for any position on the set. I had a good deal of lighting and cinematography experience from school and the grip and electric department opened up. I definitely fell in love with being on set and being part of that process. As time went on, I felt that gaffing offered less and less for me, so I eventually made the move to shooting. The big decision for me came after gaffing the film Green Room, which was an absolute treat in every possible way. I really do hope that I have those sorts of fantastic creative experiences again in my life. Patrick Stewart as the bad guy. Dischord Records as the soundtrack you couldn’t have picked a better movie for me as a person. I was just so enamored with that film. I was gaffing for one of my heroes in cinematography still to this day, Sean Porter. Sean also came up through the gaffing world and was always looking for new ways to do things. When Sean and I would do small projects together and we could execute the lighting however we wanted to, we would do things like “No Kino Fridays” just to challenge ourselves.

Filmmaker: Bumping up to a higher position can be anxiety inducing. You’re basically given up steady work and risking a chunk of your income and there’s no guarantee that your old place in line is still going to be there if the leap doesn’t work out.

Mackie: It was a huge consideration and the move still affects my life. You can’t underestimate the amount of challenge that comes with making a jump like that in the film industry. I think it’s actually more difficult than just getting into the industry, especially if you’re not as particular about what [job you want to do] starting out. Survival is tough no matter what in this industry and it’s tough [when you switch positions] to spend all your time at first rejecting a good amount of the calls you get. I did end up leaving Seattle and moving to Los Angeles and a good part of that was due to just the reality of trying to move up as a gaffer and trying to redefine myself as a DP.

Filmmaker: Walk me through the timeline of Language Lessons. How much prep did you have?

Mackie: It was an experiment from the very beginning and we put it together very quickly. I think it was three weeks between the first call from Mark and when we started shooting. None of us had any idea if it would work, but there was quite a purity to the filmmaking. Mark is always looking to reduce the amount of commotion around set and make it as true and real and honest as possible. A major chunk of the time was getting the rigs [used for recording] up and operational in those three weeks. That was quite a scramble. For me, preparing the rigs and giving them to the actors was like sending movie astronauts into space, because there was almost no [in person] contact between people at that point. That was pretty much the nature of the experiment: We can’t be together, but let’s try to make something anyway.

Filmmaker: What was the filming process like?

Mackie: We would all get on a Zoom call, then essentially all just muted, turned off our video and let Mark and Natalie perform the scene while we were recording, both on Zoom and through rigs I was remotely controlling. Then we would finish the take, everyone would unmute and we would go through notes. We had a bilingual script supervisor that was also helping with the Spanish dialogue. Aleshka Ferrero, our editor, also should get a tremendous amount of credit for the work she did to bring this thing alive and make it work through all the challenges. This was in June of last year, so we were all getting our Zoom legs underneath us and would work eight to ten hours at most. We shot, I think, for eight days, minus pickups and a few little tiny pieces. It was quite an experience. I was amazed how much like a real movie set it all felt like once we got it up and running, but then you’d hang up on the Zoom call and just be back in your apartment with the pandemic raging outside.

Filmmaker: Tell me more about these rigs you constructed for recording.

Mackie: It was completely one of a kind. (laughs) My goal was primarily to capture the best image possible while also allowing the actors to focus on their performances. My biggest fear was that they would knock it out of the park with a performance but forget to press record. So, essentially the way that I operated was, I built these two rigs with webcams controlled through [the actors’] computers. I used a remote log-in program, so I would basically be running their computers from my house [and] have control over the webcams and the recording.

There was a discussion early on about whether to use actual webcams. It also came down to limitations of cameras, like DSLRs for example. At the time I couldn’t find any software that would allow me to control those cameras and their settings remotely. I ultimately landed on using and embracing real webcams to give us a very authentic look. So, we went with the best webcam that we could find, which was made by Logitech, and that allowed us to do a 4K capture. I ended up doing some things to try to improve the image quite a bit. I built filter holders onto them for very small camera filters and added a diopter and some diffusion filters in front of the lens. The diopter really did help. It added a little bit more depth of field to the image. It’s difficult to get depth of field on those cameras because the sensors are so tiny, but the diopters did move it toward the cinematic world.

Filmmaker: You had to attach mics and lights to that rig as well?

Mackie: Yes. Audio was actually fantastically important to us and we worked with a sound mixer that Mark has worked with before. He was very helpful in setting up a directional boom mic that was directly behind the camera and a recorder on the computer that recorded movie quality sound. Then I added Elgato Key Lights that were also controlled remotely through the actors’ computers. I had color temperature and intensity controls. I also sent each actor a box of grip gear, some incandescent clip lights and some diffusion. Going back to this idea of sending movie astronauts into space, I just basically sent them a grab bag of things that they could use and also that I could use through them. Having Mark as my gaffer was a good turnabout. (laughs)

Filmmaker: Right. Oh, how the tables have turned.

Mackie: Yeah! That is just the magic of what Mark brings. Before we made this film we had just lost Lynn Shelton and at that moment it was still very, very raw. We came together with the spirit of “Let’s make a movie together, because everything in the world right now is not so great.” Everyone just gave themselves over to being part of this fluid filmmaking team. Natalie was clapping the slate and doing some data management. Mark was doing some lighting. There was no road map at all to make something this way. A day before we started shooting, we were still on Zoom figuring out how things were going to work. Like, how do we roll a take? What’s that process when you’re making a movie this way? We had to come up with whole new protocols.

Filmmaker: I read an interview where Natalie talked about having to come up with a solution to control the computer’s fan on the fly because it started kicking on mid-take and messing up the sound. What’s another unforeseen mid-shoot complication you had to deal with?

Mackie: There’s a scene where Natalie is outside on a Zoom call with Mark and walks him [through the rain forest]. We could have used the laptop rig for that, but it just didn’t feel right for her to take that rig on a walk outside. For that scene we actually built a different rig with two phones tied back-to-back and recorded using FiLMiC Pro. However, you can’t multitask and use both Zoom and FiLMiC Pro on one iPhone. So, we basically had the Zoom call on one phone so Natalie could talk to Mark, then we were recording on this second phone that we rigged to the back and offset. Then Natalie had to figure out the right angle to hold the rig because she could only see the Zoom call with Mark. She couldn’t see what she was recording [on the second phone] at all.

Filmmaker: You had Light Iron’s Ian Vertovec as your colorist, who I know from his work on David Fincher films. How much could you really push around the image from those webcams in the DI?

Mackie: The DI was such a challenge. In this day and age we’ve become used to having a lot more flexibility. It was like color correcting on a knife’s edge in so many ways. I really can’t thank Ian enough for the work that he did and the patience he had with us in working with these cameras. The dynamic range was quite limited. The second day we discovered that the cameras—which were the fanciest webcams we could find—would not expose outdoors. I had to go to the Logitech website and call them and they were like, “Oh yeah, it doesn’t support shooting outside.” (laughs) Luckily,C I had put those filter holders on there and we were able to ND down the camera so we could get those shots.

Filmmaker: Honestly, I’m just amazed that you were able to make such a good film using this technology. Because of OVID I’ve had to record a lot of interviews on Zoom and WebEx that I would’ve shot in person before the pandemic, and it’s like the bane of my existence. You’re trying to reposition people away from windows and practicals so the cameras aren’t making unwanted auto exposure decisions. Then you have to try to get them to adjust their webcam’s frame so their head isn’t a super tiny spec and at the bottom.

Mackie: Yeah, so you know the feeling. (laughs) I just tried to embrace the limitations as best we could. Our goal here was just to serve the story.

Filmmaker: There’s this argument at the moment about the necessity of seeing new releases in theaters and whether streaming releases are somehow not “cinema.” And then here’s your movie in theaters, made in a format that many of us have spent the last 18 months staring at on our laptops. I know people are passionate about that debate, but I did find the idea funny that someone might see Language Lessons on a giant screen and then watch Dune on their phone.

Mackie: (laughs) You bring up a really interesting point. Until this moment I hadn’t really put that together how much of a flip-flop it is, that in the “church of film,” which is what one of my professors called theaters, you have a movie that is about people being trapped within their screens. You know, even though we started this as an experiment, I always had a feeling that it would end up being more than that. I’ve been involved with so many indie productions with people like Mark and Lynn where, on the surface, it’s just ten people making a movie in a friend’s house, but they just have such a talent for being able to find interesting stories and crafting them in a way that connects with audiences. And I do think stories like Language Lessons, stories about building relationships when we’re physically apart, can be cathartic and therapeutic right now.

Matt Mulcahey works as a DIT in the Midwest. He also writes about film on his blog Deep Fried Movies.