Back to selection

Back to selection

Wanda: Film from the Future

Wanda

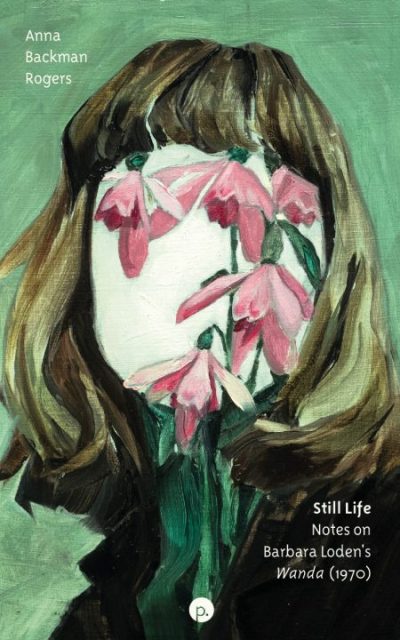

Wanda Still Life: Notes on Barbara Loden’s Wanda (1970)

Anna Backman Rogers

154 pages

Punctum Books, 2021

One of the complaints made about feminist films of the 1970s and ’80s was that they were too experimental, too avant-garde, too elitist. They refused the pleasures of pop cinema. They skipped the well-told story and refused the escapism of character identification. And beauty? Forget it!

Take Barbara Loden’s Wanda, from 1970: it’s a desolate portrait of what New Yorker critic Paulene Kael dubbed an “ignorant slut” in a film described by Jump Cut’s Chuck Kleinhans as “flat and opaque.” Indeed, Wanda, who is based on a woman Loden read about in the newspaper, lacks all ambition and her pathetic spiral into crime is captured in stark, often downright ugly imagery topped off with an affectless performance. How would feminists ever catalyze a broad-scale revolution with films as unappealing as Wanda?

In her terrific new book Still Life: Notes on Barbara Loden’s Wanda, Anna Backman Rogers, who teaches at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden, eloquently offers an answer to this question. Rather than deny Wanda’s ugliness, Rogers passionately calls attention to it; she repeatedly points to the film’s slowness and mundanity, as well as to Wanda’s passivity and hesitancy, her muteness and numbness. However, in all of this, Rogers uncovers not bad screenwriting and shoddy filmmaking but instead writer/director/actor Loden’s quiet, unflinching subversion, and she uses this to argue further that not only should we watch films like Wanda, we must watch them. “This is a film that holds within it the sadness of the world,” Rogers writes, “and asks us to attend to that as an ethical calling. It tells us, starkly and simply, not to turn away from suffering.”

While this is Rogers’ thesis, which is powerfully argued, the book also ponders how and why Wanda has gained cult status, and why for many of us, the film feels uniquely our own. “Wanda is a film I have thought about every single day since I first saw it,” Rogers writes, “and it continues to teach me things.” Here, Rogers names the feeling that many viewers have in response to the blunt force of Wanda, which is often followed by a sense of discovery, intimacy, even identification: Wanda, an undiscovered heroine of inscrutable pathos, is always our Wanda! However, while that sense of acute recognition often feels quite singular and personal, Rogers demonstrates how the film is not only speaking to a bevy of cult fans, nor is it simply an iconic emblem of the past; it is instead a prescient alarm for the present.

Still Life is divided into three parts. The first section contains nine sub-sections, each one carefully situating the film in a particular way. Rogers begins with the material history of the film, how, when and with whom it was made. She highlight’s Ross Lipman’s role in discovering the original print of the film in 2007, the film’s restoration, and its digital release by the Criterion Collection in 2019. She also traces a history of critical responses far more incisive than Kael’s, citing a key essay written by film scholar Bérénice Reynaud originally in 1995 and then re-published in Senses of Cinema in 2002 that brought the film back into a broader conversation. Reynaud pointedly queries the historical erasure of the film, not only by mainstream critics and audiences even after it won the Critics Prize at the Venice Film Festival in 1970, but by feminist historians. “While Wanda has been ignored by every major text of feminist film theory published in English over the last 20 years, Akerman, Potter and Rainer have become household names,” claims Reynaud. While this spins me into a fantasy world where feminist filmmakers are indeed household names, Reynaud’s point is pertinent. Wanda might not fare well commercially, but what made the film so dismissible by feminists, too?

Rogers, building on the work of critical theorists of affect such as Sara Ahmed, Lauren Berlant and Ann Cvetkovich, goes on to read the film in relation to a broader political context. She shows how Wanda condemns the mendacity of the American myths of success and happiness, writing, “By attending to failure, to impossibility, to impasse, we can attain a greater understanding of the ways in which happiness, as a disciplinary ideology, comes to shape our understanding of what it means to be a person in the world.”

Rogers then narrows her critique to gender, noting that Loden’s quite brilliant portrayal of Wanda demonstrates total disenfranchisement. “Wanda’s passivity can be seen as a radical indictment of the multitudinous and infinitesimal ways that women every day are forced to subjugate and deny their personhood,” explains Rogers, who goes on to assert that Wanda continues to reverberate now, in 2021 because it is “a film from the future since its politics are so prescient of the endgame currently being played out politically, economically, socially (and ethically) on a global scale.”

In short, then, with this opening section of the book, Rogers joins a vocal cadre of feminist critics across a nearly 30-year history who have had a profound experience viewing the film and in turn, have argued for its relevance. What Rogers brings to the conversation is the idea that a film from 1970 speaks so powerfully to our current moment, a time inviting a radical reimagining of representation; an attention to affect and the sensorium as viable modes of cinematic expression; and a desire to attend to ongoing lived trauma for so many. While the final three sub-sections would be stronger with some rearranging, the writing here burns with the high heat of a blowtorch.

The second section of the book is, curiously, a shot-by-shot reading of the film, zooming in close to study framing, camera movement, cutting and performance. After describing several scenes in flat detail, Rogers offers her interpretation, noted in italics, including her own affective responses to what she has witnessed. Reading this section is strange, like listening to a baseball game on the radio. If we’ve seen the film, we can recall many of the images; however, to then read Roger’s often eloquent response is at once thrilling, validating and wrenching. Yes, we think, I remember that scene, and yes, the obliteration of consent. Yes, ineffable sorrow. Ah, yes, silence, only silence. Fade to black.

The final section acts as a brief coda, returning to the book’s larger argument and the desire not to include Wanda within a broader canon of feminist filmmaking that championed “images of women” or celebrated self-empowerment. Instead, Rogers notes that the film “holds a disarticulated, muted, numb, and seemingly passive woman at its core and demands that the viewer reckon with the very possibility of self-definition as an inaccessible privilege.” This is a feminism that needs to address race and class as much as gender, and one that must reimagine the role of film in figuring, and perhaps even galvanizing, modes of resistance.

Still Life is very much a book in conversation with other scholars and critics who have written about Wanda, including Elena Gorfinkel, Natalie Léger, Kate Zambreno, Amy Taubin, Marguerite Duras, Amelie Hastie and even Isabelle Huppert. Rogers gathers and sifts through much of the historical information available elsewhere, but she situates this information within her own felt experience of the film and presents her own take, one that refuses the myths of betterment and potential proffered by neoliberalism. She sees and celebrates Barbara Loden’s brilliance and quiet ferocity, and, as in the best examples of autotheory, deftly integrates personal experience with philosophical inquiry. More importantly, Rogers meets Loden’s powerful drive to represent a woman’s experience with her own equally searing indictment of American myths. Rogers reclaims the mute and the numb in order to say that this is what suffering looks like and we cannot look away.