Back to selection

Back to selection

Breaking Bodies: Julia Ducournau on Titane

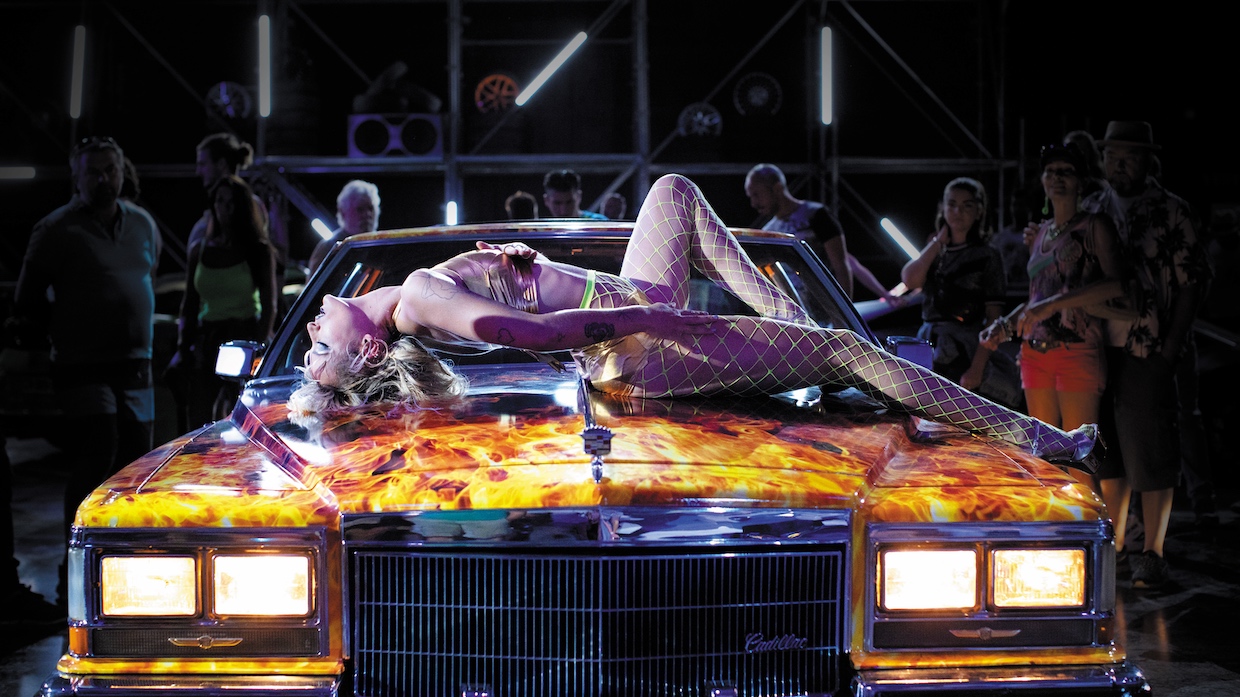

Agathe Rousselle in Titane (Photo by Carole Bethuel, courtesy of NEON)

Agathe Rousselle in Titane (Photo by Carole Bethuel, courtesy of NEON) Following her breakout film, the high school cannibal romp Raw (2016), filmmaker Julia Ducournau doubles down on her predilections for freely reconstructed human flesh. The Palme d’Or–winning Titane strays even further from traditional narrative logic, emerging as a baroque investigation of the power of bodies to morph in response to the desires and violence of both people and machines. Taking its title from the metal plate installed in a young girl’s head after her father (Bertrand Bonello, in a fun bit of casting) crashes their car amid her aggressive fury, it is, yes, the movie where a woman fucks a car (two, actually) but also a remarkably devoted ode to physical transformations in all their forms.

Titane hurtles along in pursuit of its titanium-encrusted protagonist as an adult. Auto show stripper Alexia (Agathe Rousselle) careens from a post-car-coitus killing spree to hiding from the police by pretending to be Adrien, the long-lost son of firefighter Vincent (Vincent Lindon), while pregnant with the child of the car she fucked. Ducournau crafts a film whose form is constantly in dialogue with its protagonists and the tools they use to build themselves anew—or to destroy others. Titane is a film about how a camera looks at women and men, and their power to shift and reconstruct themselves in dialogue with that gaze and the gaze of others. Titane is out now from NEON.

Filmmaker: When I watched this film, there’s a lot here, but first and foremost it’s a film about flesh and how we modify it with technology, with testosterone, with piercings, with metal plates, etc. And I really love the way it’s almost like a dance film, watching these bodies be thrown around, especially at the beginning. You have this incredible sense of movement, from a real dance to these bodies falling down the stairs. So, I wondered, as a filmmaker, when you’re going into these spaces, how do you conceptualize your relationship to motion physically? Is there anything you did technically that was different in terms of how you were coming at these bodies in this film with your camera?

Ducournau: It depends on what you want to convey, really. For example, the car show dance [which introduces Alexia as an adult], and the shot that leads her into the dance, is not there to convey the same motion [as] the one in the big scene when [the firefighters are] dancing together, or when she’s dancing on the truck at the end. The car show I wanted to be a oner, a plan sequence, because I wanted an evolution in the way the audience watches the girls in that scene. So, at the start, it’s all about trying to recreate the pseudo-male gaze that objectifies the girls as much as the cars, in which they are at exactly the same level. For that reason, the POV is actually pretty external even though it’s supposed to represent a gaze, but [it’s] a gaze so objectifying it’s used [to create] distance [from] the girls—there is no empathy, no humanity. [When] we get to her dancing, it becomes way more organic—we’re actually way closer with the camera because it’s her reclaiming her own narrative and being active in the shot, whereas the other girls were passive. It’s a oner with a lot of movement, as you’ve seen. At the end, we put the camera on a crane. That is no longer you who is looking or gazing at her from the outside, but she who is looking at you. [The] character is completely active and owning the scene—she was not at the beginning. That was the idea in this whole movement. But even though she’s reclaiming her narrative and being active in it, we are still playing within the realm of gender stereotypes.

The scene when she’s on the truck [a sexualized dance performed by Alexia in front of her firefighter coworkers at the end of the film] is shot in a more still manner because it’s all about her movement, not the camera movement. It’s about her presenting herself as a complete being—now it’s no bullshit, it’s not the camera [that has] the gaze. The tracking on the firemen, the way they look at her, echoes the looks of the car show audience, which was completely a bland objectifying distance, not giving a shit. Here, the firemen look at her either like she’s the messiah, or they look away because it’s too much for them to see. The idea here is to try to direct it as a real revelation in the sacred sense. This side tracking shot on the firemen is a shot that I tried to [make] my interpretation of a shot in Salò, or the 120 days of Sodom. In Pasolini’s work, there is a shot on the youngsters at the beginning before they get into the castle.

Filmmaker: It’s my favorite shot of the whole film.

Ducournau: Oh, really?

Filmmaker: I love that shot. It’s so beautiful.

Ducournau: I love the whole film for other reasons, but this shot is my favorite one, as well, because there is still something that is incredibly innocent in a way. They all look so innocent and pure, they are young, they don’t know what is coming. There is something that is, again, a bit sacred, and obviously the sacredness is going to be completely complicated by what’s afterwards. But it’s still there at this moment; that’s why I like it.

Filmmaker: It’s funny you mentioned that because in that moment we are viewing them as a viewer, too. We don’t know the relationship of gazes that those young people in Salò are going to be entered into after that. And after that, Pasolini’s construction of the gaze is very rigorous. From that point on, they’re never free again. But your film really plays out at this musical level, the way you carry us from scene to scene, in particular. I was fascinated by your scene edits in this film because the scenes are constructed around gazes in a way that is somewhat traditional, but then when we move between scenes, the sense of kinetics carries us and papers over a lot of the narrative logic. Could you talk about your editing process in terms of building up the film as a whole from scene to scene, and what, if any, the role of music was in that? This is very much, as I said, a dance film.

Ducournau: It starts with the writing—obviously, it’s huge editing work afterwards, but it’s there in the writing. When I was writing the first two or three drafts, I was still contained in a very academic structure, three acts, and struggling with it. At some point, I realized that this academic structure [did] not fit the energy I wanted to give the film, and I got rid of it—which was not easy, to be honest, because it is a bit soothing to know that we have real arcs and where things are going to be. [But] I didn’t want to know where things were going to be, and I didn’t want the audience to know, either. So, I decided to think about more of a narrow [structure], built in layers more than acts. You start with something that is incredibly baroque looking, very bloated, very in your face, very saturated colorwise. And, scene by scene, you take out a little bit of this layer, [like] the moment she actually meets Vincent—it’s a lot about shedding skins, nearing the essence of the characters, of their love and of humanity. Or at least I’m trying. And when you think like this, especially in a script where there are very few words, music is super important at the base of the film. The score was really built exactly like a reflection of this shedding of layers throughout the film. We go from something very animalistic that is fucking you up—these are my impulses, a lot of dry drums, lots of atonal choir—and it becomes very tonal at the end because we finish on Bach. You can’t be more tonal and sacred than that.

The way I write, I don’t like to do [establishing] shots. I never do it. Even if I do it once, because I’m scared, I’m going to edit it out instantly, the first day. I never [show a] complete [view of] anything. I like to try to get to the heart of the scene and then cut right away. For me, the heart of one scene has got to talk to the heart of the other scene, and so on. This is how you build this birth of love, of humanity, of a new world in the end, by having the scenes [in] dialogue together. I hope what I’m saying is not too abstract.

Filmmaker: No, I think that’s perfect, and funny, because I was going to ask you about touch next. If there is a narrative progression in the film for me, it’s about how the actors touch: how they touch themselves, how they use objects on themselves and certainly how Vincent and Alexia touch each other. It seems quite intentional, and I was wondering how you as a director were working with these actors in order to build these modes of movement. Was there a thought behind how touch plays out in the film?

Ducournau: For me, the main thing is looks more than touch because touch comes when you work on the looks. When you make the looks evolve, [it] then becomes more natural to [have] characters touching, which obviously becomes necessary. Where there is a clear evolution for me with touching is—[there’s] really true disgust on the part of her biological father, violence between them at the start, then [the touching] starts being softer and softer throughout the film. The pivotal moment [is] when she comes back [to the firehouse] and says, “Daddy, wake up” instead of putting the pick [the hair pin Alexia uses to kill people] in his ear. So, there is this evolution in this shot: She could’ve killed him very violently, and she just [says] this. Touch has become softer. Then, we go to the part where she decides to be Adrien for good.

So, for me, the evolution of touching, it’s pretty clear, but it has a lot to do with looks. At the start of the film, she is someone who has never been looked at by her father—he keeps ignoring her or looking at her indirectly or looking through her, in a way. It’s a reason why she doesn’t have any control at the beginning. I think there are others, but let’s say that in the film it’s the reason why. The fact that he doesn’t look at her and she doesn’t have any control makes her have impulses that completely overflow from her in a very chaotic way. She’s only led by her impulses—she doesn’t know emotions; she doesn’t know love at all. All that keeps her standing are her impulses.

Vincent is not at all a white knight, I certainly don’t want people to think that because for me he’s the opposite. Vincent is incredibly neurotic and scary. He’s, in a way, the opposite of her biological father [with regard to] their neuroses. It doesn’t make him better. I think he is very scary at the beginning. He has this fantasy and wants to shape her like his fantasy in a very selfish, destructive way. It makes him overbearing and violent and intrusive, so I really want to insist on the fact that he also undergoes a very big transformation and acceptance of her humanity. But the thing that he has that her biological father doesn’t is the “looks.” He constantly looks at her, obviously, because she represents his fantasy. So, he looks at Adrien, and he molds Adrien all the time, and I do think that this gives her comfort. It’s the wrong comfort because it’s not really hers, but it’s comfort anyway, and it’s the first time she has some, you know? That’s the first time she gets the shape of an identity. And no matter if it’s the right or wrong identity—we don’t care about that. It’s just that at least she has control, and she’s been craving that for a long time. It’s how she is going to try to get in touch with this role that she has decided, not that he decided.

Filmmaker: To follow that up: I’m sure to some degree you’re exhausted with talking about gender in this film, but I think it’s important, when we talk about what we just talked about, to ask what is the relationship between this concept of gender, what Vincent creates for Alexia or Adrien, and the tools that they use in the film? Because, again, you see many, many physical objects being used to create a body and a gender, even a new body.

Ducournau: What I’m trying to portray here is how gender is a fantasy. Vincent [is] trying to make her fit his own fantasy, which is bending her gender, but at the end, my idea is to show, is it really relevant whether she is his son or not? He says, “You’re my son no matter who you are.” That’s the only thing that he cares about. It’s no longer a matter of gender. But what was important is that even though this scene is crucial, it’s very important to not stick to that. It’s really appealing because he’s saying that he accepts that she’s not his son genderwise but still sees his son. But this has a lot to do with desire rather than just gender. When we’re talking about two people who love each other [for] all the reasons—familial love, romantic love, sexual love, companionship—they see each other for who they are, and who they are is the person who the other one loves. That’s all that matters. So, I think that the relationship between my characters, with regards to gender, is that gender is irrelevant to label their relationship.

Filmmaker: Do you see the ending as utopian?

Ducournau: That’s a good question. I think I’ve always said that my film was optimistic. That’s just how I think. I just think that gender is irrelevant to define someone. I do think that love is capable to make you see through that and any other representation. That’s something I believe. As long as I believe it, it can be completely utopian because at least I’m one person here who believes it.

Filmmaker: Yet, you’re fascinated with the techniques of gender. You started with what it is for a man to look at a woman on the screen, no?

Ducournau: No. For me, if you want to debunk those stereotypes, you have to show them first, and after that you just kick their ass if you want to. That is what I tried to do in [the] writing of the film, as well with the lighting. For example, the bluest, whitest, harshest lights are always on the so-called feminine parts of the film’s story. And the firemen are always bathed with pink [light], which is socially constructed to be associated with women. [But in] the mosh pit scene [when Alexia dances to gabber music at the firemen’s party near the end, right before she does her sexy firetruck dance to their dismay], I used this white light for her to blend her totally with the other guys and to show that she’s really doing everything she can in order to fit Vincent’s fantasy because she loves him that much at that moment.

Filmmaker: You work with a lot of practical effects on the set. You do make use of genre. How do you conceptualize making use of these sci-fi and gore effects? What’s the planning? How do they make it onto set?

Ducournau: That’s a super long process, especially on this one. For Alexia’s character, at the end, she was covered from her face to her thighs in prosthetics. It starts with me talking to my head of special effects a lot, giving him some references. It’s stupid, but when you have a role with some metal it’s like, how is the metal supposed to look? Obviously, The Terminator was a huge reference there, when he has his face open. But I wanted something a bit more moist, a bit more organic, so we did some tryouts with silicon and latex. That’s all in the lab.

When you work with prosthetics, you have to have a basis that is kind of believable. For example, it’s stupid, but the question of her breasts: Through the pregnancy, her breasts will grow, obviously. So, do we [enlarge her] breasts or do we leave them as they are, assuming that it’s a very weird pregnancy, and it’s going to look weird? And [it’s] like, “No, I think we need to have the breasts growing, as well; otherwise, it’s too weird, and it’s going to be less believable.” At the end, we needed to see the veins, that she’s going to burst. I wanted you to feel that she was going to explode, literally. So, it was a lot about designing the veins.

With the stretch marks: We had a lot of stretch marks at the end. But you have to build the body of a real pregnant woman, then you add your elements of genre. Right away, I told [makeup artist] Olivier [Afonso] that in this film I did not want blood. I switched it to oil. I did not want it to be too gory. I wanted the wounds to be quite clean, somehow, because I think that it gives a weirdness to it, more uncanny than if you had added a lot of liquid [that] could have been bleeding out at some point. You remember the end of Under the Skin, yeah? When she takes off her skin? I love this shot, and I love the special effects there. I think it’s gorgeous because it’s plain. There is nothing dripping, drooling from that. I’m not saying that I tried to do the same because that’s not the same as my film, but the feeling that I felt when I saw it is something I was trying to reproduce.

It’s always a matter of violence with prosthetics. You never want to go too far because otherwise it’s going to look cartoonish. And it’s going to be comedic in places where you don’t want it to be comedic. For example, in the killing in the house: Obviously, it was a comedic scene. So, here we exploded with blood, it’s all over [her] face because that’s funny, you know? But if you want something emotional or striking or disturbing and all of a sudden everyone cracks up, you are doomed, you know? It’s always a lot of balance.