Back to selection

Back to selection

“Given Enough Time and Space, Any Difficult Scene Can Be Solved”: Editors Jean Tsien and Aldo Velasco on Free Chol Soo Lee

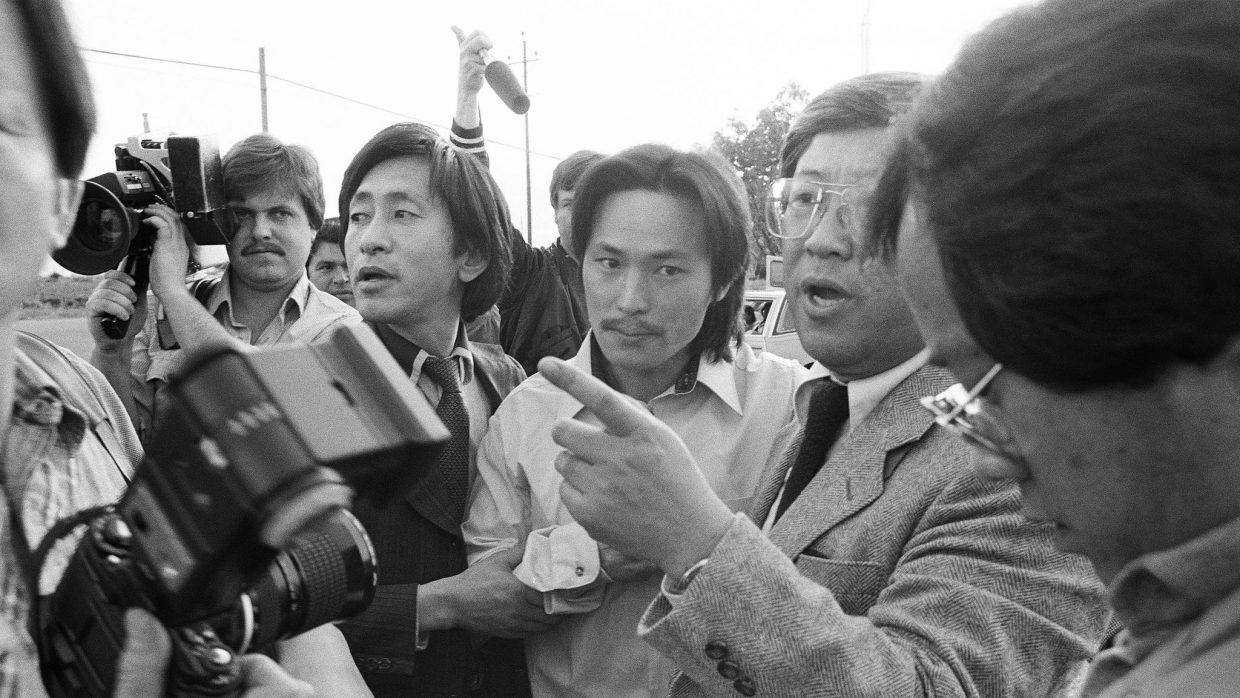

A still from Free Chol Soo Lee by Julie Ha and Eugene Yi. (Photo: Grant Din)

A still from Free Chol Soo Lee by Julie Ha and Eugene Yi. (Photo: Grant Din) With Free Chol Soo Lee, directors Julie Ha and Eugene Yi examine the life and legacy of Chol Soo Lee, a Korean immigrant wrongfully convicted of committing a murder in San Francisco’s Chinatown at the age of 20 due to the false testimony of white tourists. When journalist K.W. Lee took an interest in Lee’s case, it spearheaded a wave of nation-wide pan-Asian activism. Editors Jean Tsien and Aldo Velasco and co-editor Anita Yu discuss how their understanding of their subject grew over time and how they ultimately decided to zero in on the film’s narrative trajectory.

Filmmaker: How and why did you wind up being the editor of your film? What were the factors and attributes that led to your being hired for this job?

Tsien: I was one of the mentors at the TFI/Camden Retreat in 2019, where Julie and Eugene were presenting their film as fellows. Soon after the retreat, they invited me to come on board as their supervising editor and executive producer. Since Eugene is an editor himself, he did a lot of the early work on the film, but there came a point where we collectively thought it would be better to bring on a full time editor so he could focus more on the directing and producing work. As a producer, I recommended Aldo Velasco, a great editor based in L.A., who I worked closely with on the Peabody-Award-winning-series Asian Americans. Aldo helped elevate the film to another level, but he had to move on to another project after six months. At that point, the team suggested that I finish the film with the help of our amazing co-editor Anita Yu, who is great with graphics as well as storytelling. So it was a wonderful editing relay and collaboration.

Filmmaker: In terms of advancing your film from its earliest assembly to your final cut, what were your goals as an editor? What elements of the film did you want to enhance, or preserve, or tease out or totally reshape it?

Velasco: Eugene had been editing a cut of the film for months, and he and co-director Julie Ha needed an outside eye. I watched the cut and was completely spellbound by the Shakespearean scale of Chol Soo Lee’s story. The cut had more of a journalistic feel, with many factual sequences that were fascinating but needed shaping. I recognized that I could provide a “music” for the film—not so much literal music as a metaphorical kind—contributing a rhythm and drive that might enhance the tragic ironies and impact of the story.

Tsien: The directors always wanted to tell the story of Chol Soo Lee through the angle of journalist K.W. Lee, but also to bring out the story of this seminal pan-Asian American movement. I focused on helping the balance between the two storylines come together.

Filmmaker: How did you achieve these goals? What types of editing techniques, or processes, or feedback screenings allowed this work to occur?

Velasco: Much of the process was taking a cold, objective look at scenes and sequences and asking how essential they were. Were they essential to the story, or cluttering it? My first strategy was to go through and cut out as much as I could. After viewing this cut we could assess how much of the story was enhanced by the omissions and how much was derailed. After that, many things were edited back in, though usually in a different form. I focused on getting the story to its essential form, with its juggling and shifting of story points. Then Jean took over the editing, and continued this process.

Tsien: One key obstacle was that Chol Soo’s voice was edited from many archival sources, and though it read well on paper, it sounded disjointed. We decided that we would tell Chol Soo Lee’s early story with voiceover largely from his memoirs, as well as the archival sit down interviews while he was in prison. Once we were able to focus in on his voiceover in the earlier part of the film, we were really able to bring out the inner thoughts and turmoil of Chol Soo Lee as a wrongfully convicted prisoner. It became much more emotional and moving.

Feedback screenings were extremely important when we were all isolated in our own homes. Normally we would have in-person screenings with a few trusted directors and editors. Due to COVID, we shared our rough cuts with great colleagues like Keiko Deguchi, Carol Dysinger, Geeta Gandbhir, Don Young from CAAM and Michael Kinomoto from ITVS, just to name a few. Their feedback was invaluable to the process.

Filmmaker: As an editor, how did you come up in the business, and what influences have affected your work?

Tsien: In my senior year at NYU film school, I took an editing class with Paul Barnes, who edited the classic documentary The Thin Blue Line. It was Paul who introduced me to the late Sally Menke, whom I assisted for five years before she left docs to work on fiction films. My greatest blessing came when Larry Silk hired me as his assistant editor. He was the preeminent documentary editor of the time, who had worked on three films that won Academy Awards. Larry was passionate about storytelling, and he always reminded me to think about the audience as I edit.

Velasco: I went to the graduate film program at UCLA, but after graduating I ended up working in private investigation for several years. When I left that job, editing was the easiest way for me to make a living. I had never planned on a life in post-production, but once I got in the swing of it, I realized it was a thoroughly fulfilling way to spend my days. Probably my greatest influence in my life and work overall was my time as a private investigator. I worked on many cases very similar to that of Chol Soo, assisting in the legal defense of falsely accused individuals, almost always people of color. My boss was a great mentor, and taught me true empathy and the art of listening to the voices that society considers negligible. During the editing of this film I spoke with him and learned that, by incredible coincidence, he had known Chol Soo Lee in the seventies in the Bay Area and knew many of the key players in the story.

Filmmaker: What editing system did you use, and why?

Tsien: We worked on Avid. Eugene had set up the project there, mostly for Scriptsync. It’s the most stable platform when you are working with large archival projects. And since we had multiple editors, it was very easy to share our media and sequences via emails.

Filmmaker: What was the most difficult scene to cut and why? And how did you do it?

Velasco: One of the most difficult scenes to cut was one that deals with the end of Chol Soo’s life and its aftermath. I don’t want to give anything away, but the sequence is both emotionally wrenching and challenging to relay, and striking a balance was tricky. Each version differently affected the ultimate meaning and takeaway of the film, so there was a lot of friendly debate and discussion as to how the scene should land.

Tsien: Difficulty is not the word I think about when I cut a scene. I believe that given enough time and space, any difficult scene can be solved. The challenge in editing for me has always been about structure and transitions. The opening of this film was very difficult for me. For the longest time, we opened the film with Chol Soo Lee’s funeral, but it didn’t transition into the first act very well, so we decided to meet Chol Soo Lee through an archival interview first. Once you heard his real voice, we could more smoothly introduce the voiceover read by Sebastian Yoon and the audience could more easily orient between the two voices as Chol Soo Lee.

Filmmaker: What role did VFX work, or compositing, or other post-production techniques play in terms of the final edit?

Yu: As we were getting close to the final edit, we decided to utilize graphics for certain scenes. During the Free Chol Soo Lee movement, there was a ballad written about him and the case, and for that scene in particular, we wanted to illustrate its lyrics, but not in the boring traditional way. So Eugene and I brainstormed a bit on the phone and joked about using a karaoke style for the lyrics. Thankfully, we had the original record sleeve, so we scanned the original lyrics and came up with an idea of using the “evidence board” as a theme, using images from the case to illustrate the lyrics in an organic way. I think the fact that the scenes we used graphics for were based in archival allowed them to live in the visual language of the film. It gave us the freedom to tell the story in an artful and creative way that blends in with the rest of the film.

Filmmaker: Finally, now that the process is over, what new meanings has the film taken on for you? What did you discover in the footage that you might not have seen initially, and how does your final understanding of the film differ from the understanding that you began with?

Tsien: Julie first told me she wanted to make this film to give peace to her mentor, K.W. Lee. But while editing, the balance between K.W. Lee and Chol Soo Lee created a conflict for me. The story needed to focus on Chol Soo, and we had to pare down K.W.’s screentime. But after watching the archival footage of K.W., I understood how extraordinary he was. Here was an immigrant who worked in the Jim Crow South and really put his own career on the line to save a wrongfully convicted young man. As an editor, my role is to serve the director’s vision to the best of my ability but also to do what’s best for the film. When the film was finally finished, I discovered in order to serve Chol Soo Lee’s story better, it was not about reducing K.W. Lee’s screen time, but about how they are juxtaposed, both narratively and emotionally.

Velasco: For me, since finishing, the film has retained its emotional shape but has expanded in dimension and scale. After months of diving into his mystery, I began to see Chol Soo Lee as a living person in my life. Though his life is certainly tragic in many ways, I grew to appreciate how he was able to create meaning and purpose in his later years. When a person dies, people always say that he or she “lives on in our memories,” but in fact, those who are left behind each create unique narratives as to the meaning of the life of the deceased. While editing Free Chol Soo Lee, I realized that’s what we were doing. My hope is that the film isn’t seen as the definitive statement on the life of Chol Soo, but as a portal to further explore his life and legacy.