Back to selection

Back to selection

“Once I Said Yes to That Film, It Changed Everything”: DP Lee Daniel on His Pre-Slacker Austin Days

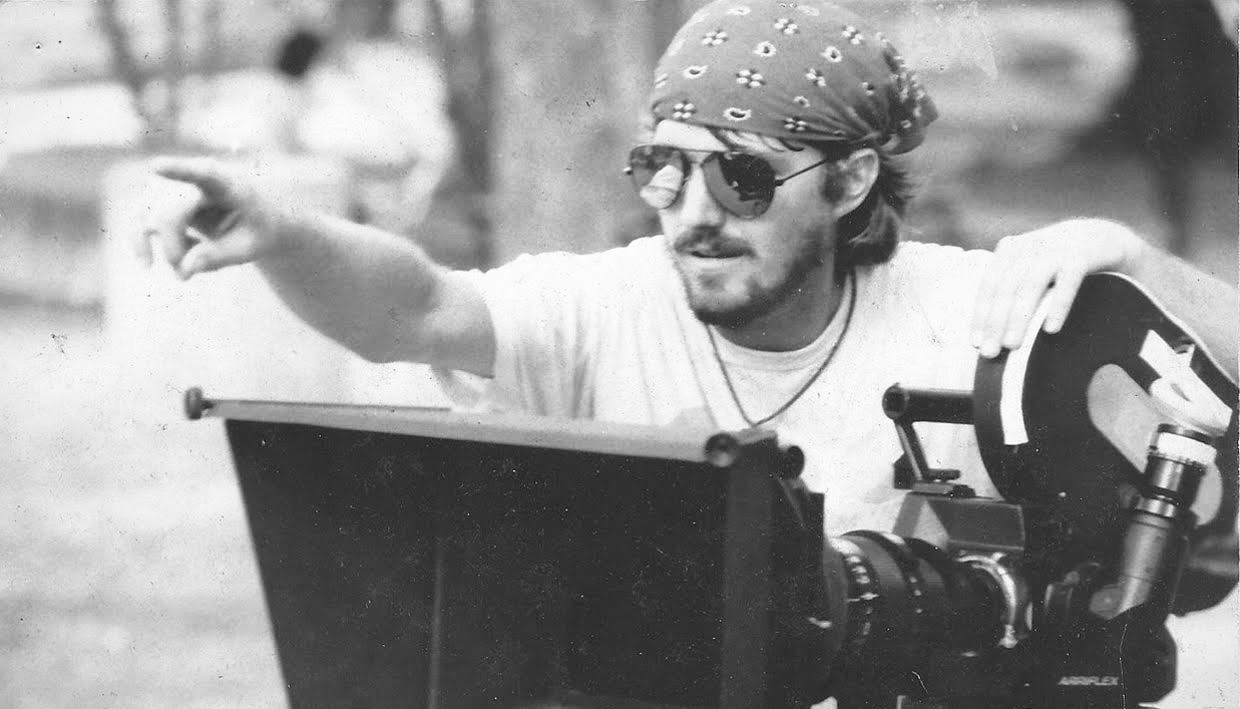

Lee Daniel on the set of Slacker

Lee Daniel on the set of Slacker Austin in the ‘80s was a college town dressed up as a state capitol, attracting a steady stream of students, dreamers, and dropouts hanging out on the edge (literally and metaphorically) of the University of Texas campus, where Lee Daniel and Rick Linklater screened foreign flicks and postmodern masterpieces in a DIY venue above a coffee shop.

Daniel and Linklater brought revival-house sophistication to a community of misfits and film fanatics when they formed Austin Media Arts (now the Austin Film Society) in 1985. The pair lived down the street from their repertory cinema in a West Campus residence that quickly morphed into a film-circle epicenter. The Finger Hut, as it was known, had a cameo in Slacker. Janis Joplin once slept in the attic. Rent was $200, all bills paid.

In the summer of ‘89, Daniel, Linklater and a core crew of arthouse urchins hit the streets of Austin to make a semi-scripted movie about the disaffected demimonde deep in the heart. Slacker, which celebrated its 30th anniversary last summer, invoked a generational zeitgeist: Daniel was the film’s cinematographer and went on to collaborate with Linklater on numerous projects, including Boyhood (2014), Dazed and Confused (1993) and Before Sunrise (1995), which Roger Ebert called a Love Affair for Generation X—“like a documentary with an invisible camera”—thanks, in large part, to Daniel’s long, uninterrupted shots.

Though best known for shooting indie classics, Daniel’s extensive work in documentary filmmaking has been just as visionary. That list includes Margaret Brown’s Be Here to Love Me: A Film About Townes Van Zandt and Laura Dunn’s The Unforeseen.With more than 40 feature-length films and documentaries, Daniel has not only made a mark on American cinema, but an Austin forever shaped by his lens.

Today, the 60-year-old cinematographer lives quietly in a high rise just off the University of Texas campus, not far from where it all began. Daniel recently spoke with Filmmaker Magazine about his career and those early Austin days.

Filmmaker: How did you first get interested in film and camerawork?

Daniel: Les Blank changed my life. When I was in high school, our class went to the town public library and watched his documentary A Well Spent Life on a 16mm projector, about Mance Lipscomb, an East Texas bluesman. I knew that’s what I wanted to do.

Our next-door neighbor, Jerry Chastain, was a cameraman—which was extremely rare in Richardson [Dallas suburb]. He worked for a company that shot commercials and did a few movies. He showed me how to load the magazines with film when I was a teenager, things like that. I remember asking Jerry about getting an internship at some point at Victor Duncan, which, back then, was the biggest camera and movie equipment company in the South. My ambition was to get into camera maintenance.

In the late ‘70s and early ‘80s there was a huge amount of money going into studios in Dallas. Las Colinas had state-of-the-art soundstages just like LA; Silkwood and RoboCop were filmed there. But things started petering out; it just never became the big Hollywood studio lot they thought it would be until the 1990s, when Ann Richards [then governor of Texas] started giving tax incentives. That’s what really kickstarted the Texas film industry. Las Colinas started renting out to rock bands; I made music videos in those studios back when I was a camera assistant. I wasn’t yet a shooter—I had a fake it till you make it approach. That’s where I learned everything.

Filmmaker: When did you get your first camera?

Daniel: I started making Super 8 movies with my older brother when I was 13. But I got a 16mm my second year at UT [University of Texas]. There was a small shop in Austin run by a guy named Jerry—another pivotal Jerry in my life—who sold mostly Leicas and Nikons. But he had one little glass display with a 16mm called a Beaulieu and I just couldn’t take my eyes off it. It had a really fancy zoom lens, and zoom lenses were rare back then. I had a job that paid $5 an hour, and I think it was $1500. Since I was going to film school, Jerry proposed we do a trade: if I could shoot a commercial for him he’d take another $600 off and give me extended credit. That commercial was the very first thing I shot. I subsequently sold the camera to Mike Judge.

Filmmaker: What was your first film gig out of school?

Daniel: I was a full-time undergrad for five years, studying anthropology and film, but dropped out after I was offered an internship at Texas Pacific Film and Video, the only production company in town. I was 23 at the time and working at a skateboard shop. A lot of great stuff was going on in Austin in ‘84/‘85, but you needed people to offer it, and Richard Kooris [the owner of Texas Pacific Film and Video] did just that.

All I knew about film in Austin was there may be an opportunity to get an internship with TxDOT or one of the state agencies for what they used to call industrial films. That’s what Tobe Hooper did a decade before me. Richard [Kooris] was a springboard for myself and so many others. After I put in all my hours as an intern, they hired me right off the bat, and gave me what I thought was a great job. I was in charge of all the equipment. Cleaning it, working on it—I was a real techie. I could take apart a camera and put it back together. Plus I had the only viable 16mm camera in Austin—I wasn’t confident enough as a DP or cameraman, but I was perfectly fine with renting it out. I was both a camera owner and a camera assistant; I’d come with everything they needed.

Filmmaker: What did you like the most about being a camera assistant?

Daniel: Being 1st AC is a technical job, I had to make sure all those actors were in focus. So, when they leaned into the camera, I had to pull the wheel while extrapolating the distance with my own eyeballs. It’s different now: focus pullers use video and high-definition monitors. Back then, we had to use tape measures. From the optical plane of the camera, you’d have to take a tape measure to the lead’s—or whoever’s—eyeball in focus, which was a real challenge because you had to learn to judge that distance. I would lay down 4 x 8 planks for the dolly to drive on, so I could base it on that measurement of eight feet. Some actresses and actors would be nervous for their eyes, so I would use a cloth tape measure instead of a metal one.

I was working on these movies of the week being shot around Austin. If there were ever any problems in the dailies, if the footage was out of focus, the studio would look to the DP or focus puller, and just clean house. That happened on a movie in Houston sometime in the late ‘80s called D.O.A. They dropped all the union workers, and I was one of the very few local camera assistants who could do it, but I had to cross a picket line—I was a scab!

Filmmaker: When did you start Austin Media Arts?

Daniel: We co-founded Austin Media Arts [now Austin Film Society] back in ‘85 with Denise Montgomery, who later died of Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. It was really heartbreaking. D was an artist on every level. I don’t think the film society would have happened without her. Most people consider D, me and Rick the founders of the film society. We called it Austin Media Arts to get better grants; we had to speak that language.

I was at UT and Rick was going to Austin Community College under the auspices of Chale Nafus and George Morris. ACC had the greatest professors, I would crash his courses. Chale and his partner were very important in terms of helping us. They would sign off on our grant applications to the city. They were so legit, and we were not. We were just students. But we got our grants and started the Austin Film Society from that.

We ran these movie nights. It was just the epitome of postmodern filmmaking. The original locale was directly above Quackenbush’s [Captain Quackenbush’s Intergalactic Dessert Co. and Espresso Cafe] on Guadalupe. We built our own projection booth and sound canceling so people could have a good cinematic experience. I was only involved with the film society for the first 10 years; it got too big, too Hollywood. I understand completely why, but I wasn’t into it. I, of course, benefited because it meant more work came to Austin. But it wasn’t for me.

Filmmaker: So the first feature film you shot was Slacker?

Daniel: It was actually Never Leave Nevada, which I believe we shot in 1988. Steve Schwartz and Louis Black from the Austin Chronicle were trying to follow in the footsteps of Eagle Pennell. They couldn’t think of anyone else to shoot it but me because I owned the means of production. Steve and Louis called me and said, “You’re the only one who’s got a camera: would you like to shoot this movie?”

[She’s Gotta Have It] had just come out, and they kept saying they wanted it to look low budget like that. They wanted it in black and white. I didn’t feel ready but ultimately agreed. Then it went straight to the USA Film Fest in Utah—before Sundance even existed—and got a distribution deal. It ran at the Bleecker Street Cinema for six weeks. I went there and watched it. I couldn’t believe it: the very first time I went to New York, there were movie posters in SoHo and Chelsea with my name on them.

Once I said yes to that film, it changed everything. They turned our whole house [Finger Hut] into a production office. I already had the camera, of course, but we bought an editing machine and brought all this stuff from Richard Kooris’ office that he graciously lent us to transfer all the sound. There was no digital anything; everything was analog.

Filmmaker: Was there a sweet spot early on, somewhere between indie and industry?

Daniel: Probably around Dazed and Confused. It was the tipping point where I decided that my career might actually be more independent or narrative filmmaking than documentary filmmaking. It took a while to get Dazed and Confused into distribution. They didn’t know what to do with it at first—there were no bankable actors. I was still very close with Rick at that time, and we were working to really build up the script. My older brother Bill had graduated high school in 1977; he was the senior, Rick and I were the freshman, so to speak, so we all compared notes and worked on themes—not dialogue, just themes. We were loving it, plus we didn’t know we’d get a $7 million budget or something like that. We were still in the independent realm, but for us it was enormous—Slacker was $23k.

Rick kept Dazed and Confused kinda secret. He invited me to his apartment one day and just dropped the script in front of me, and it said Dazed and Confused: Written by Richard Linklater. I said to him, “Rick, I didn’t know your name was Richard!” He made the right play, he really did. He knew what he was doing.

Filmmaker: Slacker turned 30 this past summer, and you turned 60 this past January—exactly half a life ago. Looking back, what are your thoughts on the film?

Daniel: I can’t tell you how many hundreds of people said they moved here because of Slacker. That was not our intention! If you look at the film you’d think, why would you want to come here? [Laughs.] It was a catalyst for something I didn’t see coming.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.