Back to selection

Back to selection

“I Was Born in Cinecittà”: Production Designer Dante Ferretti on Collaborating with Pasolini and Scorsese

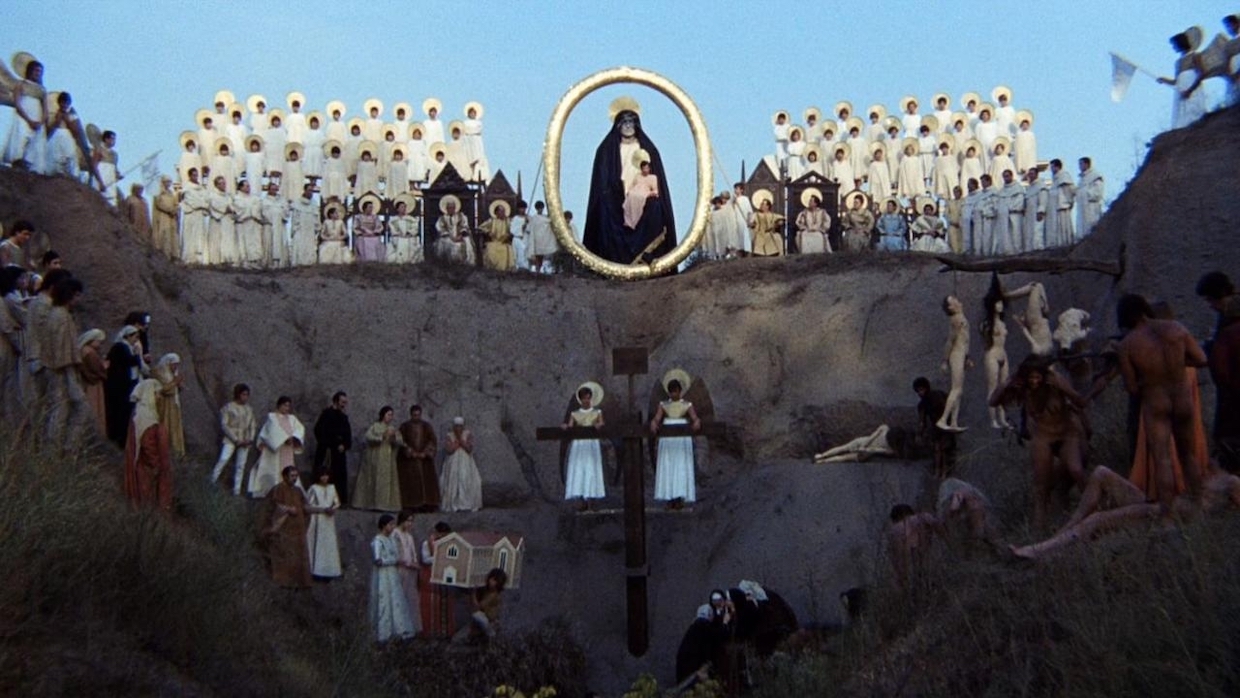

A Dante Ferretti set for The Decameron

A Dante Ferretti set for The Decameron Saturday, March 5th marks the centennial of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s birth, and numerous retrospectives are being held worldwide commemorating the late Italian filmmaker. Tragically murdered at the age of 53, weeks before his infamous Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom, was set to premiere, Pasolini’s output continues to attract cinephile appreciation, political discourse, cultural reevaluation and a fair share of controversy. “His movies, influenced by his struggle to reconcile his concerns with Marx, Freud and Christ, often drew him into conflict with the Roman Catholic church and with secular authorities,” reflected The New York Times in 1990.

Currently running through March 12th, the Los Angeles-based Academy Museum of Motion Pictures presents Carnal Knowledge: The Films of Pier Paolo Pasolini, a series—co-realized with the world renowned film studio, Cinecittà, and the film archive Cineteca di Bologna—presented almost entirely on preserved 35mm prints. The retrospective launches what is intended to be a five-year partnership between the Academy Museum and Cinecittà in support of an annual series focused on Italian cinema.

Pasolini felt like an excellent filmmaker to begin the initiative, especially given his (and his tireless production designer Dante Ferretti’s) rich history with the Rome-based studio. “Thanks to the amazing work of programmers like James Quandt at what was then the Cinematheque Ontario, and now the TIFF Cinematheque, I had seen people putting together these very big Pasolini series,” Bernardo Rondeau, the Academy Museum’s Senior Director of Film Programs recently told me. “I, perhaps naively or ambitiously thought, ‘Maybe we can put something together like that here at the Academy Museum, especially if Pasolini’s films have been circulated around [other institutions].’ I thought that since Pasolini continues to remain such a key figure in the history of Italian cinema, an entity such as Cinecitta would surely have done some [restoration] work on his films—and luckily, they had. Putting together this series slowly became a very successful example of expectation meeting reality.”

The Academy’s retrospective pairs various shorts and documentaries alongside the feature selections, shedding further light on the director’s painstaking process. “We wanted to create as complete a portrait of Pasolini, as filmmaker, as possible,” Rondeau says. “What we’re attempting through the program is to present a linear, chronological journey through his body of work. The shorts we include are an attempt to fill in gaps over the course of his career. In some instances, Pasolini made films that were almost short accompaniments to his features. When we screened The Gospel According to St. Matthew last week, we paired it with Sopralluoghi in Palestina per il vangelo secondo Matteo, a short documentary Pasolini made about location scouting in Palestine for that film. Sometimes there was a clear one-to-one relationship between a Pasolini feature and a documentary short that we were eager to present together.”

To kick off the festivities last week, Dante Ferretti was invited to introduce the retrospective’s opening night selection, Accattone (1961), Pasolini’s feature debut. Ferretti, a three time Academy Award winner for his design work (alongside his wife, set decorator Francesca Lo Schiavo) on Martin Scorsese’s The Aviator and Hugo and Tim Burton’s Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street, has amassed an astonishing number of Italian filmmakers—Liliana Cavani, Federico Fellini, Marco Ferreri, Franco Zeffirelli, and countless others. Ferretti graciously hopped on the phone with me last week to discuss the retrospective, provide an update on current projects and share words of wisdom he’s acquired over his now half-century-long career.

Filmmaker: I wanted to start by asking about how your working relationship with Pier Paolo Pasolini began. You recently introduced the director’s debut feature from 1961, Accattone, at the Academy Museum in Los Angeles, but I believe your first collaboration with him came a few years later.

Ferretti: Yes, that’s true. I was still very young. My first movie with Pasolini was The Gospel According to St. Matthew (1964), where I worked as an assistant production designer. I then worked with him on The Hawks and the Sparrows (1966) and Oedipus Rex (1967) in an assistant role. But when I worked on Oedipus Rex, I was almost working alone, as the production designer I worked under [Luigi Scaccianoce] was always making more than one film at any given time. [In the late ’60s, Scaccianoce was at work on Federico Fellini’s Satyricon, on which Ferretti would go on to serve, uncredited, as assistant art director.] By this point, Pasolini and I had developed a working relationship and he would ask, “Dante, what would you like to do?” So, I always did what I could and did the job right, and he was very happy.

I was then hired to make my first film as the head production designer: Pasolini’s Medea (1969), with opera singer Maria Callas. They called me just at the last moment to offer [me the job]—the producer had previously called another production designer but it didn’t work out. Once I was hired, I arrived in Cappadocia [in central Anatolia] two days later to begin work. I then continued as Pasolini’s production designer on The Decameron (1971), The Canterbury Tales (1972), The Flower of the One Thousand and One Nights [also titled Arabian Nights (1974) in select international markets] and then finally Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom (1975)—not only my last movie with Pasolini but also, unfortunately, the last film he ever made.

Filmmaker: You’ve mentioned in previous interviews how Pasolini didn’t care for filming on interior soundstages. He always preferred to be outside, repurposing real locations for film sets. Is that also a preference for yourself?

Ferretti: I have done both. It’s true Pasolini always wanted things shot on location. We might change the look of a location somewhat, but being there was always the most realistic [option]. When we would shoot in a studio, it would never be for more than a few days. Everything else would be shot at the real place, even if we would change many things upon arrival. Pasolini didn’t like to repeat [locations] either. We would adapt a place, a location, so that it would match exactly Pasolini’s idea for it.

After working with Pasolini, I went on to make six movies with Fellini. On his films, everything was shot inside a studio. Then, for Jean-Jacques Annaud’s film, The Name of the Rose (1986), everything was either built on location or in a studio at Cinecittà. We built an entire church outside of Rome [for exterior shots]. Later on, I began working with Martin Scorsese, and on his movies, most were shot on stages. For example, when we made Gangs of New York (2002), all of that movie was built and shot at Cinecittà. We didn’t shoot anything in New York, because we built everything in period detail on stages in [Rome]. On The Age of Innocence (1993), we shot that film primarily in Troy, New York, but sometimes used stages as well. When we used real locations, we had to change many things. So, we always find ways to readapt.

Filmmaker: You’ve previously discussed your involvement in the actual architecture and building of sets and your willingness to build all 360 degrees of a set if necessary. Is that something that you address and work with a director on on a location-by-location basis? Do you sometimes create smaller sets based on the framing of a specific shot?

Ferretti: The sets I build usually consist of an entire set made up of four walls. That way, the director can rotate the camera 360 degrees if they wish. I like to build the entire set first, but sometimes it depends on how many walls the director needs. Sometimes the shot will only encompass three walls, so I only need to build out those three pieces. But typically when you build a set for interiors, you’ll want to build and include all four walls. That way, the director can feel free to put the camera anywhere during production. You have that freedom in [the moment].

Filmmaker: You’ve said that the most important thing for a production designer to do is to understand the period, and I was wondering about the type of research you like to do. Are you looking at a lot of photos or reading up on a lot of history?

Ferretti: I go back and look through many pictures of the time period and everything that [existed] within it. I try to be like an architect who exists within the period of the film. I like to invent things. I don’t like to copy other stuff, because the other stuff has already been made. I always want to make something new. I will, of course, read the script and, [if the source material is based on one], the book, then look for period-specific pictures and paintings. I store each of these things into my mind, then try to make it my own.

Filmmaker: You’ve also said that it’s important to make mistakes—that if the production design looks too perfect, it can look fake.

Ferretti: Yes, it’s very important to make mistakes, because when you make a mistake, it makes everything appear more believable. When everything is perfect, it looks too fake.

Filmmaker: Your working relationship with Cinecittà goes back several decades and you keep an office at the studio where you store many of your original sketches. You were even hired to design the studio’s theme park a few years back! I wanted to ask about your relationship with the sudio and how the freedom and access they provide with has influenced your career.

Ferretti: I’ve been working with Cinecittà close to forty years. At this point, they are somewhat like my home. When I go to Cinecittà, everything is in shape. I work well over there. If anyone ever asks me, “Where were you born?” I always respond, “I was born in Cinecittà.” I’ve worked on movies all around the world—I’ve made many movies, for example, in Los Angeles and in England, like Martin Scorsese’s Hugo and Kenneth Branagh’s Cinderella and Tim Burton’s Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street at Pinewood Studios and Pinewood’s Shepperton Studios—[but] Cinecittà remains my home. I have done so many movies at that studio that sometimes I can’t remember exactly which ones! After all, I’ve made somewhere around 85 films in my career.

Filmmaker: You’ve had long-lasting working relationships with some of the most renowned filmmakers of the 20th century. What would you attribute to the success of those partnerships? Is it a filmmaker’s personality, a clarity of vision, the way they tell stories or something else?

Ferretti: It might be better if you ask this question [of] those directors! They initially will call me because they may have seen a movie I [worked on] and say, “maybe he will be a good designer for my movies too.” I always try to do my [best]. It does not always work out this way, but I try. I read the script they send to me, of course, but first I want to know who the director is as [a person]. Then they will call me, we’ll have a meeting and, from there, decide if we are the right fit to work together.

Filmmaker: There were reports that you would be teaming with Scorsese again (this time, in Oklahoma’s Osage and Washington Counties) on his new film being released later this year, Killers of the Flower Moon. Did that ultimately come to fruition?

Ferretti: No, it did not. I began work on the film two years prior to when we were to begin [filming]. I visited Oklahoma to scout locations and work on designs. I also started, briefly, to work on building [the sets], but thenwent home to Rome for Christmas to see my family, and during this break the pandemic arrived. The movie was put on hold and I had to remain in Italy and could not travel. For two years thereafter, I could not make any film. From what I know of the [Killers of the Flower Moon] production, they had some of the [budget] cut, as the movie was very expensive and, at that point in time, didn’t know when they would be able to restart.

I was then called to work on another movie and, since we didn’t know when production would resume on Martin’s movie, said yes to this other offer—but they had to cancel that one too. However, while I was working on this other movie, Martin was able to restart Killers of the Flower Moon, I was [unavailable] and they had to hire another production designer, Jack Fisk. I have made ten movies with Martin [including Killers of the Flower Moon] and he recently had to call me to [apologize], saying “Dante, I’m so sorry, but I had to call on another production designer to move forward with the film.” I designed much of the film, but I don’t know [what they kept] or what it will look like when it’s released. It may feature some of my work or it could be an entirely new project at this point. We’ll see if my production designs are there. [laughs]

Filmmaker: I’m sure you’ll be called upon for Scorsese’s next project. Whatever he works on next, I’m sure he’ll reach out and you’ll share your eleventh collaboration together.

Ferretti: Hey, it’s enough, we’re already at ten [films]. But I am still young. I tell people I am only 60 years old and that my birthday comes once every three years. I also tell people that I am very tall and have very long blonde hair. [laughs]