Back to selection

Back to selection

DIY Photogrammetry: Sasha Litvintseva and Beny Wagner on Constant

Constant

Constant One of the highlights of this year’s International Film Festival Rotterdam, Sasha Litvintseva and Beny Wagner’s 40-minute not-quite-documentary Constant considers how the meter was standardized. It’s a topic that sounds drawn from one of the numerous popular history bestsellers of the last few decades explaining how some obscure topic is actually the key to understanding how the modern world came to be—and, indeed, one of the three source texts Constant credits is Ken Adler’s The Measure of All Things, which tells the story of the codification of the metric system. That story, however, is wild, involving in part a seven-year, on-foot journey undertaken by two scientists during the French Revolution to codify the final distance of the meter. Theoretically, a meter is a fraction of one out of ten million meters, or the distance between the pole and the equator; in practice, that distance turned out to actually be 10,002,290 meters, as verified by satellites in the late 20th century. That breaks down to each meter being off from what it “should” be by the tiny amount of 0.23 millimeters. As Constant hauntingly explains, the inaccuracy was, in part, attributable to errors in human perception—completely correct measurements would require the elimination of the human altogether.

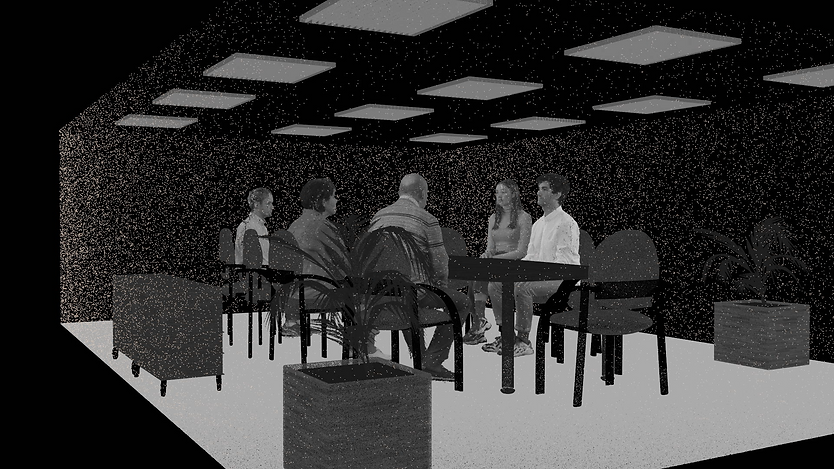

Litvintseva and Wagner’s first collaboration, 2020’s A Demonstration, began by reflecting on a moment in European history when, as the opening titles explain, “self-proclaimed naturalists competed with each other in a race to catalogue the world. Birds, plants, rocks and monsters were all equally real to them.” Constant likewise delves into European history and its oft-sinister present-day ramifications, including the ways in which measurement interacts with land ownership. The film’s first narrative scene takes place at the National Physics Laboratory, a body responsible for the standardization of forms of measurement. The camera performs a slow 360 pan from the middle of a table, taking in the filmmakers, two scientists and one PR person. One of the scientists turns on the PR person, then starts proposing the kind of movie the duo should make; as he speaks of a sequence depicting cavemen, an CG animation of one appears on the desk. Throughout the film, Litvintseva and Wagner continuously take raw science and similarly deploy it to artistically disorienting ends; their depiction of the journey undertaken by the two scientists, for example, creates a type of image (above) that I’ve never quite seen before.

Following its Rotterdam premiere, Constant makes its US premiere tonight as part of MoMI’s annual “First Look” series.

Filmmaker: This is part of the “Monsters, Measures, and Metabolisms” project. Can you talk about when you first conceived of that and how that works for you?

Litvintseva: I guess it developed fairly organically. When we made our first film together, A Demonstration, we had a sense that we’d want to continue working together around those same themes from different angles. At that point, it wasn’t clear whether it’d be a trilogy or something else. We were developing this film at the same time we were working on the book that accompanied A Demonstration, and it was not that long ago, as we were starting some writing around Constant, that we actually formalized the project as a trilogy. Now we know what the next project is and how they fit together.

Wagner: I think there were moments in the process where we had a kind of false sense of certainty about what the bigger thing was going to look like. Things inevitably change dramatically in the process of coming to be. Now, it seems clearer than it ever was while we were making it.

Filmmaker: What has that clarity led you to?

Wagner: It’s retroactive. There’s something emerging that was very opaque while it was actually happening. With Constant, we got funding for an entirely different film, then that fell through and we started Constant with completely different intentions. We thought we were going to film in this lab, then that fell through, then COVID happened. So, there was no way to know what that was going to be before it happened.

Filmmaker: The opening sequence introduces a story and a setting, then gradually reveals the possibility that this may be entirely constructed. How much of that is real?

Litvintseva: You mean at the meeting table? Almost all of that is exactly what happened.

Wagner: There are important changes, of course.

Litvintseva: Some of the most substantial things are in the very last part. We really struggled with how to deliver the issue of the ultimate inability to get access as something that’s conceptually interesting in itself, and not as us being bitter—“Oh, these people are the gatekeepers, so they’re the villains and we’re the victims.” That’s not at all what’s going on. So, we actually had to change quite a lot of things to give some of our thoughts in their words.

Wagner: It might sound counterintuitive, because there’s some humor involved. They represent a certain gatekeeping force. We thought a lot about what it means to set up a dichotomy of us and them. It’s a very powerful tool in cinematic storytelling, or in storytelling in general, because people want to have a clear idea of who the villain is, who the hero is and where they’re placed in between those possibilities. Most of the time, we view things as a lot more complex than that, but complexity doesn’t register so well as a narrative form.

Litvintseva: We really did have a meeting with two scientists and the PR person. Those aren’t their actual names, but one of them was a Russian mathematician and the other one was a male English data scientist, and a lot of what was said in the first and second sections where they appear—including the caveman animation—all of that actually happened.

Wagner: The thing that I remembered most was this very surreal moment where the scientist suddenly turns to the PR person and says, “Oh, the thought police over here.” That was very much a gesture to us, to make it clear to us that they weren’t on the same side—but for us, as total strangers asking these people if we can enter the institution, that was completely bizarre. And that really is the kernel of the story. This PR person, who doesn’t know anything about what’s going on in this lab, is responsible for this decision. The scientists who were interested in talking to us were honored, in a way, to have someone who’s interested in what they do, because that doesn’t happen very much in their life. So, they were really keen to interact. The way that power is distributed in that room, in an institution that prohibits that from happening—that distance between someone’s agency and their desire seems like a product of measurement, in a way.

Filmmaker: This leads to my question about photogrammetry, which is a visual tool and also, I suppose, a way of measuring things. It’s also a way for you to stage what is essentially a static scenario in a visually compelling way. You’re credited as both doing it, and I’d love to know more about how you work with it, when you started working with it and how you conceive of it in this storytelling vein.

Litvintseva: We learned about it for this project. Precisely, as you say, it is a tool of measurement almost over and above the byproduct image it generates—that’s why we were interested in using it, and in many other peculiarities of the way that this way of capturing indexical information has a relationship to stillness, movement, space and time. As we kept working with it, those things kept unfolding in ways that were extremely relevant to what we were dealing with.

Wagner: For example, the field was scanned with a drone that took thousands of images. Those images are geo-tagged and can be put together to create this point cloud. The software for it is remarkably accessible, we learned. We had never done anything around this before; it had actually seemed pretty inaccessible.

Any kind of 3D modeling has a very direct relationship to labor and energy, in the sense that if there’s a lot of labor and a lot of energy available, you can make extremely high resolution things; if there’s not so much available, then you can make not-so-high resolution things. So, the guy who was doing it for us, when he arrived at the corn field in France, didn’t understand why we would want to scan this field, because it was going to create blurry images. He’s a professional photogrammeter. He does a lot of architectural models and they’re millimeter precise. [From those, his clients can] make a one-to-one scale model and work with that in CAD software. So, for him to be scanning a corn field that’s moving slightly in the wind, he knew we wouldn’t get a good resolution image out of that, and that ultimately became interesting for us to think about in the broader history of measurement. A precise measurement requires that something be still.

Litvintseva: The way that this would happen in a professional environment would cost something like thousands of pounds per person, which we did not have available. In a professional environment, there would be one of those circular rigs that has, like, 200 cameras that all go off at once, photographing someone from every possible direction. Then, those photos would be fed through the software and create this really neat point-cloud model, because there’s no discrepancy between the position of the body from different angles. The way that people do it in a DIY sense—which is a totally established thing that we followed—is to photograph, or even better, film someone from every angle, but with a single camera, which we found takes about three minutes. So, it’s an exercise in that person keeping completely still, or as still as possible, to then achieve an image that is kind of singular and not blurred when it becomes three-dimensional.

Wagner: The resulting images that you see are remarkably similar to the process that was [once] necessary for photography. It’s like a long exposure except that it’s not at the same time.

Litvintseva: And a lot of aspects, from the event when you capture the person to when you’re able to get it into the software and clean it up pixel by pixel from different angles, were extremely laborious, and a new and unfamiliar way for us of engaging with the meat of an image.

Filmmaker: The idea of computer imagery being DIY is a little bit counterintuitive, but I suppose we’re at that point now.

Wagner: So, actually what happened is, everything was still in lockdown here in the U.K. We got in touch with this company that offers this service and has the rig. They were like, “You can’t come in because of lockdown, but you can do this DIY thing where you just take a bunch of photos and we’ll stitch them together for you. We’ll charge you 3,000 pounds for that.” Not even to use their rig. Then they were like, “Here’s a tutorial on how to take the photos properly and do the lighting.” That tutorial linked on YouTube to another tutorial about what kind of software to use on how to stitch it together, and we were like, “Wait a second. Maybe we can actually do it ourselves.”

Litvintseva: We then experimented. The best quality images came with just shooting 4K video, walking around someone, then [shooting] again from the top and again from the bottom, then exporting all of them as stills and sifting through them. There would be [5,000 images], then [we would whittle] them down to, like, 300 of the crispest with no motion blur and everything perfectly in focus. [That process] in itself could take a couple of days of looking at images that are all exactly the same. What we found through doing these experiments is that it needs to be—

Wagner: Lit uniformly.

Litvintseva: From every direction, and also in such a way that moving around that body doesn’t create a shadow when you’re creating the initial images. There’s also certain colors that the person couldn’t wear, because dark basically sinks the light into it.

Wagner: When we were learning about shifts in measurement standardization in early modern Europe, we became really interested in working class superstitions that arose around measurement. The main book we were reading located most of them in Eastern Europe between the 1600s and the 1800s. For example, there were a lot of superstitions around measuring the harvest—if you measured the harvest, it would make the harvest the year afterwards be poorer. Or, if you measured the cloth that you were using to make a shirt for a child under the age of seven, that child would stop growing. Or, if you measured medicine in a bottle, the medicine wouldn’t work anymore. A common theme in those superstitions was this idea that measurement arrests natural processes of growth. That common denominator is happening simultaneously with the prolonged process of land enclosures and shifting the terms of land through measuring them in ways that didn’t account for labor, the human body and its relationship to the land. So, we started thinking about these stories as a form of cognitive dissonance. These measurement standardizations very deliberately make themselves difficult to understand, and these stories were a way of reclaiming some kind of agency. That’s why I like this relationship of photogrammetry to stillness, and stillness as the precondition for accurate models. Working with a model that does have movement in it creates a painterly, ghostly image, exactly because the measurement aspect of this technology is being bent to do something it’s not supposed to do.

Filmmaker: I’m curious about the image where it looks like the scientists are walking in two different directions at the same time. I’m not entirely sure what I’m looking at. It kind of looks like two GoPros that have been stitched together in the middle at the same focal horizon point, but I don’t really understand what it is or how you did it. I’m also curious about the question of performance. At first I thought, you’ve given these two people a fairly mechanical task, which is to walk, and their bodies eventually get exhausted and display that themselves. But as it went on, I was like, “Oh, they are giving performances of a sort.”

Litvintseva: To kick off how the image is made, very, very good guess—that’s really close to how the thing works. It’s shot—as are all the shots in the French Revolution section that have this strange fisheye vibe—with a 360-degree camera, which creates a spherical image. Why your guess was so impressive is because what the camera actually is is a GoPro with lenses on either side of it. They create a perfectly spherical image together, and there’s a number of different ways that fits with the theme. We were initially drawn to it through this quite simple formal link between the spherical image and the idea of the globe that they’re out to capture. But as we worked with it, we realized that there’s almost a stronger relationship between the way that 360 cameras have to erase themselves from the image computationally—there’s a blind spot that it stitches together computationally—and the efforts of Méchain to erase himself from the observations.

Wagner: One of the things that drew us to the 360-camera was that we realized that we were putting people in 18th century costume and we don’t have any experience working with actors. We perceived all kinds of traps. One thing we really didn’t want was to try to achieve some kind of realism with the camera, because we felt like that would inevitably fail. So, we were thinking, what does it mean to make these images, and how can we stretch the possibilities of that and use something hyper-contemporary? Anytime you’re telling a history, you’re constantly negotiating the tension between what you want to make an image of and what you want to make it with, and how those two things speak to each other. We wanted to push that to the extreme: we’re telling a story about early modern Eastern Europe in photogrammetry, we’re telling the story about the French Revolution with this 360 camera.

Litvintseva: What’s very odd about the 360 camera is that there’s no behind the camera. So, anything to do with how one would usually think about composing an image and being very explicitly “not in it” as you’re looking at it through the viewfinder—none of that operates, because everything that is anywhere near the camera is going to end up in the spherical image. The payoff of that is that you can then do framing and camera movements in post, which is a whole world of things that is exciting. But while you’re shooting—and consider, this is the first time we’re working with actors—we had to give them direction, give them the camera, then run away, hide in a bush for a few minutes, and not be able to access what happened on camera until…

Wagner: …until they’re done—

Litvintseva: —and we were looking through the footage. So, it was crazy.

Wagner: And I think they thought it was really strange as well. They were obviously open to do it, but it almost seemed like we didn’t care. [chuckles] We gave them clear instructions, but then we ran off and just had to trust them. You mentioned the simple directive but then also the emotion and physical exhaustion, and that was really what this part of the film was about, the physicality of it. The meter is presented as this abstract thing that’s always been there and always will be there. The foot was physical, or the digit—we understand intuitively that those were related to the body, so we think about them as physical things, but we don’t think of the meter as a physical thing. That was a very deliberate intention on the part of the makers. But to get to that point was this incredibly arduous process, and we really did exhaust them. [When] the actor Derek [Elwood] is climbing up that hill, there’s a moment where he stumbles. He had been walking for about eight hours at that point.

Litvintseva: Carrying this really heavy telescope in this intense heat.

Wagner: We had a lot of footage from that day, and we took a tiny portion of it that was remarkably real. What was really good about Derrick’s performance is that he never broke character in that space. So, he’s not delivering lines or anything like that, but I think he does really embody that.

Litvintseva: He has a very expressive face, but a really nuanced control of how that works. So, even in the simplest moments where he’s walking or just looking, he’s able to bring something to it. We discussed with him what those things might be, but in the moment he had to just do it without being able to get feedback because of the peculiarities of the technology.

Filmmaker: I looked up the three texts that you’ve drawn upon for this narrative. I think I was expecting them all to be academic texts, not popular histories of sorts. The film is in this place between being very straightforward and very strange at the same time. It has this attraction to narration and is, in some ways, very easy to follow. At the same time, as you make clear in your essay “Never Odd or Even—On Palindromes and Metaphors,” you have very little use for conventional ideas of dramaturgy as necessary or inevitable. I’m curious about what it’s like for you to navigate that push-pull, of serving narrative but not certain conventions about narrative.

Litvintseva: Every project unfolds in a different fashion in relation to this question. Our previous film, A Demonstration, is infinitely more abstract if we’re talking about this continuum of narrative and legibility—it’s really just about accumulation of images and movement. Here, as we dealt with the material, it became clear that the best and most compelling way to do it justice is to have narration, and we really grappled with what that means and exactly how to phrase it. The texts that we cite as reference—one of them is a popular history, and the reason we cite it is that a lot of the detailed information about what actually happened on that journey we gleaned from there. One of them is a work by this Polish Marxist historian, and another one gave us another very useful piece of information but is a much broader academic text. But we wrote the script over the course of a year and a half, something like 20 drafts.

Wagner: We worked from the presumption that, like us before we started working on this project, most people don’t know anything about the history of measurement standardization. So, there were a few different issues. We wanted it to be in a storytelling mode, initially. At one point, we called it “bedtime stories.”

Litvintseva: Just describing an event rather than being in any way analytical.

Wagner: But that didn’t do everything we needed it to do, so there was this back and forth.

Litvintseva: Initially, we were trying to have the three different sections—the early modern, the French Revolution, and the contemporary that we participated in—match the tone of delivery. But you can’t really do that, because one of them is a very contained event that happened to us, one of them is a description of very specific historical events which we have access to and can verify, and one is a much broader, more dispersed historical movement. We realized we have to tell them all in slightly different modes.

Wagner: I haven’t read the essay that we wrote in 2019 that you’re mentioning since then. This new project created new problems; it wasn’t possible to go to past ideas to solve these problems, they needed new solutions, You mentioned [that] it is a very odd film, and there were moments when, as I could start seeing the shape that it was taking, it was like, “What is this? What did we do?” But I think the parts that are odd, in order for them to be odd, have to be in tension with something else. So, there’s a way in which there had to be a certain steadiness to the narration for the strange things, both in the script itself and in the image, to [register.]

Litvintseva: Also, the essay, from my distant memory, was critiquing not storytelling as such, but this very particular kind of story structure with the arc of beginning-crisis-resolution. Even though there’s three stages of this history that the film engages with, hopefully it becomes clear that it unfolds in this spiral movement, where things repeat but also complicate the conditions of the previous stage, and there’s no resolution in sight. The meter was supposed to democratize [measurement relative to previous standards], but then created its own kind of authoritarianism. There’s this continuous push and pull that is in no way resolved in the present.