Back to selection

Back to selection

Extra Curricular

by Holly Willis

Simple Machines: The Inspiring Teaching of Experimental Animator Jodie Mack

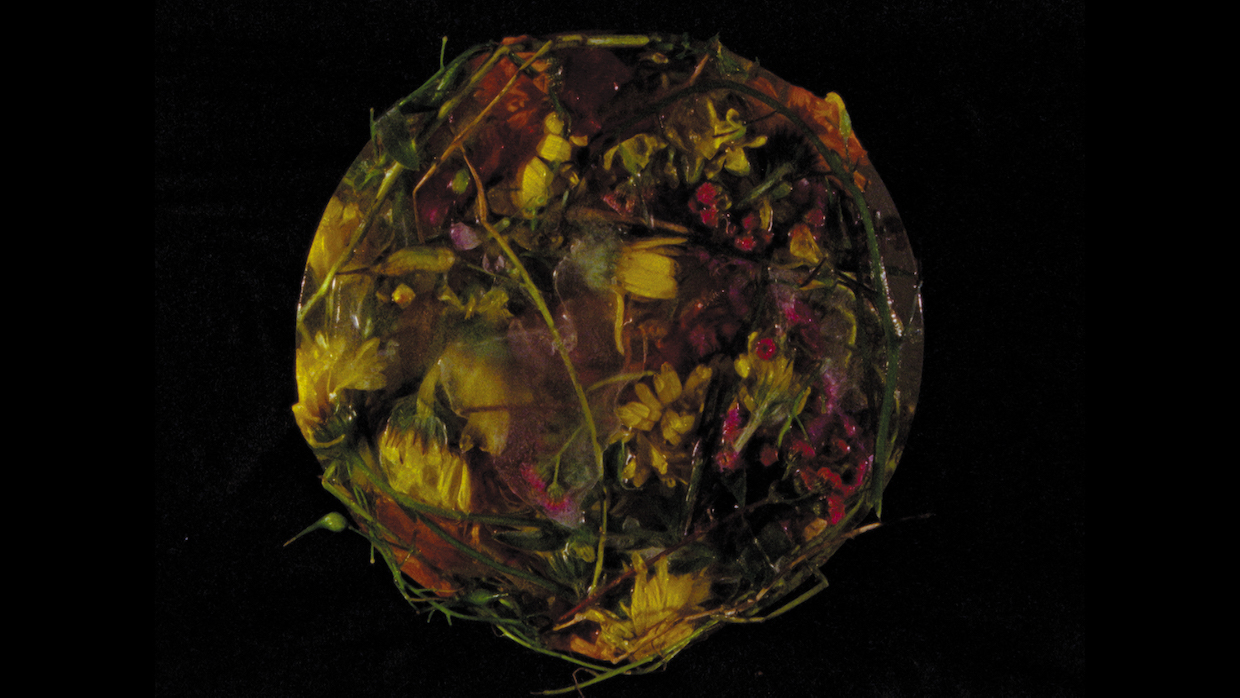

Wasteland No. 3: Moons, Sons (courtesy of Jodie Mack)

Wasteland No. 3: Moons, Sons (courtesy of Jodie Mack) “Find the note, and then deviate,” urges experimental animator Jodie Mack. The colorfully clad artist is a third of the way through her antic presentation to the November 2021 Film Friends gathering hosted by the Echo Park Film Center. Now in its second year, the monthly online series this go-around is focused on “simple machines” for filmmaking. Mack has been cheerfully showing some of her own creations, like a bicycle-driven zoetrope, but speedily moves on to her love for singing. “My voice is a simple machine!” she rhapsodizes before breaking into a wide-mouthed croon, one or two notes above the whir of her electric toothbrush.

That imperative—find and deviate—might well be the artist’s mantra for a keen teaching practice based not on delivering knowledge but on creating spaces that nurture growth and transformation. Mack, who earned her MFA in film, video and new media from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and boasts an eclectic body of brilliantly vibrant experimental animations, is an associate professor of Film and Media Studies at Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire. The desire to find the note and then deviate not only parallels the basic gesture of animation’s frame-by-frame transformation but points to her timely reimagining of filmmaking education. Mack’s teaching philosophy represents a welcome intervention in the neoliberal classroom where educators are often expected to talk of learning management, ROI and, of course, deliverables.

“I teach a class called ‘Water in the Lake: Real Events for the Imagination,’ which is based on a book of the same title by Kenneth Maue,” Mack says, describing one of her recent classes at Dartmouth. In this case, students planted seeds and nurtured a garden over the course of the quarter, considering notions of growth and caregiving alongside art and filmmaking. This simple, shared act again embodies animation as a form—incremental small changes lead to something bigger—but also brings students, locked in their bedrooms for a year during the pandemic, back into contact with one another and the rich materiality and organic systems of the world.

Maue’s book offers a series of prompts related to performance and improvisation for musicians, and Mack has repurposed them as catalysts for students to create time-based work, often through the lens of nature. “One of the scores is called ‘Three Days of Red,’ where someone is supposed to record every red thing they see for three days,” continues Mack. “There were several videos that responded to this prompt, and they were all completely different.”

Mack says that she wrote to Maue about the class, sharing some of the students’ work, and he responded by sending more poems and prompts. “One of the pieces that he wrote for us was called ‘The Freedom of Everyone Working Fluidly,’” continues Mack. The poetic prompt is delightful, and both Maue’s generosity in sustaining a relationship with the students and the emphasis on fluidity point to Mack’s vibrant teaching philosophy. “I do think this is an essential part of being an educator: enlivening knowledge or inspiring the possibilities of what that might be, as opposed to knowing an objective truth,” she says.

Mack also teaches Dartmouth’s “Introduction to Film: From Script to Screen,” which enrolls between 50 and 60 students each quarter. Provoked by the pandemic to reimagine the class, she invited the students to collectively remake Ballet Mécanique, the beautiful Cubist film by Fernand Léger and Dudley Murphy from 1924. “Each student recreated a minute of the film with a very limited set of tools,” she explains, adding that for the summer version of the class, students remade Glimpse of the Garden, Marie Menken’s magical short film from 1957. “I made a gallery show of the student work,” she continues. The exhibition included dozens of plants, and entering the gallery became a full-body sensory experience. “I remember that we had a lot of conversations around this idea of what a garden is, and to what degree we can look at the human impulse for control, especially in nature. What is a gardener? I found this really inspiring, of course, because I do see teaching as kind of like gardening.”

Teaching as gardening is a very different model for education than most of us learn, and Mack takes it very seriously, likening the differences in scale between annuals and perennials to the difference between learning that is more immediate and learning which unfolds over longer periods of time. “As we think about what it means to throw teaching buzz terms around—like ‘student-centered classroom’ or ‘democratized education’—I think a lot about the lineage of ‘author’ from priest to expert to genius to pedagogue to orator to professor, and this kind of stifling

seriousness and authority that is contained within terms like these, which are undoubtedly rooted in patriarchy and white supremacy.” Rather than rule over the classroom with noxious authority, Mack prefers to open up a space for experiences of learning.

Mack’s perspective about teaching stems in part from her own background. “I am the first person in my family to actually graduate high school and go to college, and I’ve taught and been a student at many types of educational institutions, from community college all the way through art schools and the Ivies, and I’ve seen a lot,” she says. “Sometimes, I feel like somewhat of an ambassador between worlds, so this idea of opening up a classroom and turning it into a laboratory of experimentation feels really exciting to me, not only as an educator but also as an artist, because my teaching and art practices are certainly interwoven.”

And what about singing? Does that fit in the classroom? “I guess for me, part of breaking down these barriers involves some self-deprecation and leveling of the playing field,” and sometimes that means not being so serious all the time. “It’s almost as if we’ve been trained that learning is a passive act or a form of consumption, as opposed to something generative. I definitely don’t stand in front of classrooms feeling like I’m the expert. If anything, I feel like going to the cinema and/or going into the classroom is an act of generosity on both parts, the part of the person who is on stage as well as for those in the audience.”

Asked what she hopes her students learn in her filmmaking classes, Mack is very clear. “I want my classes to deliver the idea of infinite possibilities. Students should come out of my classes with their expectations lubricated, so that they’re not so rigid in their understanding of different forms and that they can really see any film or work of art as a combination of form and meaning where the form and meaning are invested together in a symbiotic relationship.” Mack pauses, and then quickly adds another thought. “And really, I want people to leave my classes understanding their capacity to be an artist and to create things.”

Ballet Mécanique remakes:

https://film-media.dartmouth.edu/news/2021/02/film-01-presents-re-imagined-ballet-mecanique

Glimpse of the Garden remakes: