Back to selection

Back to selection

19 Months from Conception to Completion: Daniel Goldhaber on How to Blow Up a Pipeline

How to Blow Up a Pipeline

How to Blow Up a Pipeline Daniel Goldhaber’s second feature, How to Blow Up a Pipeline, takes its title and broader inspiration from Andreas Malm’s non-fiction manifesto, published by Verso. Malm’s book is heavy on the language of comrades and cadres, an exhortation to ecoterrorism to the already sympathetically inclined—and, as a friend pointed out, it’d be more accurately titled Why to Blow Up a Pipeline, as instructions aren’t provided. While Goldhaber’s version of How to Blow Up a Pipeline isn’t a manual as such, its commitment to depicting the means by which one might achieve its title goes much further than most. Eight protagonists from all over the country converge in west Texas to do the titular deed; as they prep the bombs and roll out heavy barrels with explosive charges to detonation sites, the film flashes back and forth to establish their individual paths to this moment. From North Dakota, Native American Michael (Forrest Goodluck) arrives as the most intense, motivated and humorless and takes on assembling the bombs; those helping him include Xochitl (Ariela Barer, also a co-writer and co-producer) and her friends Theo (Sasha Lane), Alisha (Jayme Lawson) and Shawn (Marcus Scribner), all from California; an equally annoying and amusing party kid duo from Portland, Logan (Lukas Gage) and Raven (Kristine Froseth); and, from Texas home court, liberatarian-leaning Dwayne (Jake Weary).

All are introduced as already concerned about the environment but dissatisfied with the scope and inefficacy of their protest options — divestment and marches aren’t enough. There are arguments about the scope of their actions and their consequences, but Pipeline‘s is more a propulsive (group) action film rather than a primer on ecoterrorism. Shot on 16mm by Tehillah de Castro and edited by Daniel Garber, it’s also a leap in geographic scale and ambition from Goldhaber’s first feature, Cam. I spoke to Goldhaber prior to his film’s premiere at this year’s TIFF.

Filmmaker: You’re a producer on the movie, one of quite a few.

Goldhaber: Seven credited producers—three producer teams, essentially. There’s the team of me, Isa and Ariela. The team of David Viste and Adam Tate were more invested in the physical production side; Danielle Mandel worked with them as a line producer. Jordan was an executive producer on our team [and] also wrote the movie. There were four executive producers, and the last two are Forrest and Sasha. Sasha’s the first actor to sign onto the movie; she made the movie real and was with us from the beginning. Forrest is a writer and a director, is actually from a refinery town and had a lot of amazing insight to offer. He rewrote all of his material and produced the entire North Dakota splinter shoot, essentially. His family is from Parshall, North Dakota, so we shot in his uncle’s house. The big flame spire shot that’s become the [key art] image [see above] is from Forrest. They call it the birthday cake. He was like, “We have to go to Parshall. We’ve got to shoot the birthday cake.”

Filmmaker: The timeline on this is so fast. I think you told me about it last June.

Goldhaber: 19 months from the conception of the idea to completion and premiere of the movie. Two months of research; four months for the script; three months to cast, finance and prep the movie; 22 days of principal photography; six months of editing.

Filmmaker: How did you do that? Is it just like, once you find Sasha Lane, everything starts moving faster?

Goldhaber: No. I mean, that definitely helped. Basically, I was taking meetings for casting before we were done, lining up about half the cast. So, I met with Sasha, Jayme, Lukas before we had even finished the script—I met them more generally, pitched and got them excited. So, I had the movie half cast, more or less, before I even went into casting and financing. For me, it’s a testament to the urgency of the material. Part of the reason we were so possessed to make it so quickly was because it felt like a story that needed to be told immediately. This isn’t something that should be part of the cultural conversation in two or three years; this should be part of the cultural conversation in the fall.

Filmmaker: In the intro, Malm says, “I finished writing this before the lockdowns. Now the lockdowns have just started. This is a blow to ecological action.” You make it a non-pandemic movie. We’re in an endemic phase now anyway, so I guess that wasn’t really a hard call.

Goldhaber: We had masks in the script and started shooting with masks. They’d read pandemic-y in the background and we just cut them. The first time we saw them on camera, it felt like it dated the movie in a weird way. The movie has this nice thing where it feels a little timeless; aside from the phones, [it could] be happening in the ’70s, and that feels really nice. It’s playing with timeless American iconography, and we didn’t want to lose that. In the world of the movie, the pandemic happened, they’re in Texas and nobody’s wearing masks.

Filmmaker: Where was your primary location?

Goldhaber: New Mexico, outside of Albuquerque, for 22 days. That was our principal photography period—everything in Texas, some of the LA interiors and the Portland stuff. North Dakota is the Michael flashback. Long Beach we shot on location. The refinery is in San Pedro and a bunch of the other college stuff was shot in California.

Filmmaker: When you’re grabbing the refinery footage, I assume you stole those shots?

Goldhaber: I would say we were permitted to shoot where we shot. I mean, that refinery is so big, they can’t prevent you from photographing it. It’s there. That refinery is in To Live and Die in L.A.

Filmmaker: Was it baked in from the beginning that you wanted to shoot on 16mm?

Goldhaber: I wouldn’t say from the very beginning. Kate Arizmendi—who was not available to shoot this, but who shot Cam—read the script as a friend, and her one note was, “Shoot this on film or else—because daylight exteriors, because it is a Western.” The feeling was that the simple production value we’ll get out of film will be so significant. But what she said that really resonated with me is, “If you treat this digitally, the only way that you’re going to get to grade it to look good is if it looks like a Levi’s ad. If you shoot this on film, you can make an actual movie.” The second she said that, it clicked for me.

Filmmaker: Did you consider digital for the night parts?

Goldhaber: No, we didn’t need it. Also, Tehillah is a genius. Tehillah would light night scenes with one light in the right place. A lot of what she does is on 16 and she has a lot of ways of doing it that really reduces the grain. She wanted to shoot 16 as if it was 35 and try to make it look like that. People are surprised it’s 16 sometimes.

Filmmaker: Were you budgeted for X number of reels and that was all you had for the production?

Goldhaber: We were budgeted for X number of reels, plus 20 percent overflow. We did the overflow and then some. We shot too much.

Filmmaker: What was your shooting ratio, do you know?

Goldhaber: 21, 22 to one.

Filmmaker: Why was that?

Goldhaber: We were very controlled for the dialogue stuff and most of the interior stuff. Once we got to some of the more action-y, two-camera stuff, we started burning film because, invariably, stuff would go wrong. There are some very complicated setpieces, and we had no prep, no rehearsal time. We were essentially figuring them out on the day with very limited light, and when you’re in a situation like that, sometimes the only option you have is just to shoot. That was a big part of it. We also cut a tremendous amount of content from the movie. The library scene was a six-minute scene. That’s four people in a room so, what is a 90-second scene, we probably shot an hour of material for.

Filmmaker: Did that happen on Cam?

Goldhaber: There was almost no lesson from Cam I could take into this movie. I was borrowing more from my background in run-and-gun music video making than I was borrowing from anything I did on Cam. They’re different films.

Filmmaker: The way the camera moves, is that a Steadicam or a gimbal?

Goldhaber: Yeah, a Steadicam.

Filmmaker: It has the embodied camera thing. The gimbal often feels weightless to me and that’s the only way I can tell the difference. Do you want to talk about that crucial first shot, with the Steadicam going down the street following Ariela as she slashes a car’s tires?

Goldhaber: That was one thing we reshot. I just did not like the first time we did it. It didn’t work; I blocked it poorly. We were running up against lunch and had a rain delay. We had one Steadicam op for almost the entire run of show, and it got to the point where me, the DP and the Steadicam op had a flow going. I could just throw Jose [Espinoza] into the scene and he would know what the vibe was. For that leg in LA, the end of our initial production period before reshoots, we did not have Jose as Steadicam op. I loved the guy that we had, but we did not have the same shorthand, and I just did not have time to get the shot appropriately. It’s not bad, it was fine, but everything went wrong getting it. I don’t think it would’ve negatively impacted the film, but our feeling was, “Let’s start out strong.”

The rest of pickups were additional material we missed. The second half of the Xochi flashback, Shawn doomscrolling Twitter, Xochi and Shawn in the dorm room figuring out what the target was going to be were added scenes, as well as Xochi coming back to a different dorm room being sad and that scene of her smoking. We did not anticipate the way that the audience was going to be engaging with the flashback structure and needed more in the first one to ease into the story and get connected to the characters.

Filmmaker: One of my favorite things in the movie is the shot from the inside of the bus when Forrest sees police cars going in the opposite direction. It’s quick but it helps so much. I can imagine that that would be the kind of thing that would take a disproportionate amount of time relative to the screen presence. What did you do?

Goldhaber: VFX.

Filmmaker: Oh, I’m an idiot. The VFX are good, I didn’t even notice them.

Goldhaber: One of the ways that you sell the budget of the movie is, you have cop cars driving by. So, [at the beginning of] that sequence, you have the cop get up at the bar. We actually did have this shot of cop cars driving [from] out the [bar] window and, because of a bunch of logistical things, the shot just didn’t look good. We started thinking about trying to do VFX but it wouldn’t have looked good. So, we left that as just sound. It’s suggested, right? We cut to the car turning on and the siren going on—that was a pickup shot, because we did not have any time with a cop car. Then we cut to Forrest on the bus. The cop cars go past—VFX. I shot it so that that could be the case; we didn’t have cop cars on that day. We cut to Shawn getting on the other bus and he hears the cop cars. Because you’ve seen them in the previous shot, you believe that they’re closer. Then we cut to our big practical set piece, Alisha approaching the cop cars—real cop cars, with the camera on the front of the car.

Filmmaker: You’re so organized. How do you keep all of this straight?

Goldhaber: I don’t. You have a huge crew to keep it straight with you. That drive-by shot where the cops drive by was also a pickup shot. I didn’t know to get that in production. Because I was the producer, I budgeted pickups. I always was going to do pickups, because I didn’t know what I needed and was so squeezed on the production time, because of cast availability, I basically withheld shooting days from myself.

Filmmaker: How about the sequence where Forrest is inside assembling the bombs?

Goldhaber: We shot that like a doc. Every setup, we had Forrest do the entire thing, then Dan cut it like he would cut a doc. We had a technical advisory who is a bomb expert and who predominantly was motivated to do this because he hates that bombmaking is always very unrealistic in movies and walked us through exactly how to make the bombs. That particular blasting cap thing, the way that he packs it—so that if it goes off, it doesn’t blow up in his face—is a very inside baseball thing. If it blows up, it just blows the back out of the giant steel box, so Michael just gets a concussion. Jordan was very much in charge of all the process stuff—everything from the chemistry to the blasting cap to how they rigged the straps to get the bombs into the holes. All of that was his domain, so I would have Jordan walk Forrest through it. Forrest also met the bomb expert and had an hour with him directly. Jordan was also reading the Mujahideen’s bombmaking handbook, pulling specific little things from that to pepper into the movie.

Filmmaker: How heavy are those barrels when you’re shooting for real?

Goldhaber Not heavy enough. I wanted them to be really heavy and my producers were like, “They have to be 15 pounds.” So, that’s a lot of fake straining. Truly, my biggest prima donna stuff on the movie was the barrels. I was like, “The barrels don’t look heavy enough.” I would put weight in the barrel, then the barrel was too heavy. It was a constant thing.

Filmmaker: I haven’t seen a real pyrotechnic explosion in a while. I don’t know if it’s as expensive as I think it is.

Goldhaber: Doing things practically in a movie it’s like, everything costs money, but what are you getting on the other side of it? And they are all CGI augmented.

Filmmaker: What does the augmentation consist of?

Goldhaber: Mostly the fire in the first two. We had to put the house one together. That was a miniature that was comped into the environment. We built a third-scale house that we lit up. The thing that was actually the hardest thing about the explosion was building the pipeline. We had to build 150 feet of pipeline. That was very, very difficult. That was the harder and more expensive thing.

Filmmaker: What’s it constructed out of?

Goldhaber: Predominantly industrial cardboard and wood. If you look at the explosion carefully enough, it doesn’t make any sense, because it should be metal. But there actually couldn’t be any metal, because metal means screws, shrapnel. So, one of the things that made constructing it more difficult was that we were actually very constrained in our building materials, because we had to blow it up. The section of the pipe they’re working on when they’re setting the bomb up was made out of PVC. Then, before we blew the pipe, they had to uninstall the PVC and install cardboard in that section so that it could be exploded.

Filmmaker: It’s only 150 feet? It seems like so much.

Goldhaber: I wanted 450 and they told me we couldn’t afford it.

Filmmaker: Is it also CGI augmented to make it longer?

Goldhaber: The only CGI in the pipe is one shot where the light hit it in such a way that you could see the cardboard and we CGI’d the cardboard out.

Filmmaker: I’m always told that this kind of invisible VFX correction is far more predominant than I generally realize.

Goldhaber: There’s about 150, 200 VFX shots in this movie, the lion’s share for this shoot in Parshall. All of our film got X-rayed coming back by the airline and was damaged. So, that was actually a lot of the VFX. But stuff like the pipeline, lots of hairs in the gates, lots of invisible split screens to merge performances together. There’s one shot where we CGI’d Sasha to not blink so we could hold the shot longer, which was a Dan pet project. They just paint it.

Filmmaker: The true promise of invisible special effects is here. I remember when I was a kid, people would be like, “We have all these tiny things, they’re not noticeable,” and they always were. This is truly not noticeable.

Goldhaber: It’s actually been not noticeable for a very, very long time, it just was more painstaking. In Alien, Sigourney Weaver refused to shave her pubic hair, and they had to hand paint her pubic hair out in all of the underwear scenes. So, this is not new, it’s just more accessible to independent filmmakers. Most of those shots are pretty cheap. The explosions were pricy, but the guy that did our explosions was passionate about the movie and gave us a steep discount.

Filmmaker: In terms of balancing ideology and the arguments that they have on screen, is there an element of you preemptively thinking about responses that you could get from people if you didn’t have those discussions in there?

Goldhaber: The discussions that we had as writers were in many ways mirrored by the characters. The breakdown of the writing team was, Jordan was in charge of a lot of the research and theory. I was chasing the genre stuff, trying to put it together in a way that was fun. Ariela basically came up with all of the characters, all the back stories, would write the flashbacks and was very much the conscience of the movie. More than anybody, Ariela was very aware of every bad faith argument that somebody might throw against the movie. She wanted the movie to engage with it rather than be vulnerable to it and was very perceptive in finding ways to bake that into character. And, at the end of the day, we saw this as a dramatization of ideas. Andreas himself acknowledges the drawbacks of certain things in the book, and we wanted to dramatize those conversations, those disagreements. When I started making this, there was a part of me that was like, “I’m going to make a piece of propaganda and start a movement,” and was very quickly dissuaded from that by my collaborators.

Filmmaker: Well, what is it now if it’s not that?

Goldhaber: A heist film. Nobody watches a bank robbery movie from the ’40s and says, “These people are trying to get people to go rob banks.” They see that movie and say, “This is a movie that’s talking about structural inequality and getting me to empathize with characters who feel like they have no other option than to rob a bank.” This movie follows eight young people who feel like they have no option but to blow up a pipeline. I don’t think of the movie as propagandistic, because there’s no cause and effect. They don’t blow up a pipeline and solve climate change. The doing of it is the narrative catharsis in the same way that it is in a heist movie. I want this movie to be given the same dramatic permission that genre is given.

If there is a moral to the story, it’s that eight people can get together—act on their idealism, cooperate in doing so have a good, well thought out plan and not get caught up in petty squabbles—and that organization is possible. Those are aspirational things that I think are communicated by the movie. I don’t think that the movie is calling for this action, despite the fact that Andreas is calling for this action. The movie is dramatizing the action, and that’s very different. The political core of the movie is asking you to empathize with this act, to understand and experience blowing up a pipeline. It’s not saying, “Hey you, audience member, go out and do this.” Part of the way that we do that is focusing on a collective. By removing your ability to heroize a protagonist, you remove the ability to call on action from the individual.

Filmmaker: How do you avoid the United Colors of Benetton effect, where it seems like you’ve cynically created a bunch of demographics that get together?

Goldhaber: The representational qualities of the movie came from us wanting to talk about the people most affected by this. By and large, the people that are in the firing line of climate change right now are people of color, poor people—you know, not privileged white people from cities. And, generally speaking, I think a lot of privileged white people from cities who are involved in this movement look kind of like Logan and Rowan. We were never thinking, “How can we architect a diverse movie?” We were reading primary source materials and borrowing characters from that, and talking to the people in our lives we know who are involved in this movement and borrowing from that. The only diversity casting that we had in the movie was, “We’ve got to have a Texan who would’ve supported Trump, that salt of the earth conservative guy.” We have to represent that cultural background. That was really important to us. But everything else is just, “Let’s look at who this is affecting and represent that in the movie.” So, the annoying white dude anarchist was part of that, but so was the young Latinx girl from a refinery town who gets engaged in political activism.

Filmmaker: I was talking to a friend last night and mentioned that one of the things I liked about the movie was the fact that there’s non-on task dialogue. People are allowed to say things that are funny in passing and they’re not plants, they’re not motifs. My friend was like, “I get a note every time that says, ‘Why is this line of dialogue in here? Does it contribute to the greater picture?’”

Goldhaber: Half of that was improv. We had a very open set, so the people that wanted to improvise, improvised. Half of Lukas’s dialogue is improvised, a lot of Forrest’s dialogue is improvised. When he goes, “I’m proud of all of you” right before they set off—that’s a very complicated shot. There was a whole first part where they load the barrels into the car, but there was too much barrel lifting, so I had to cut it. This is our last take of this really complicated two minute shot, we haven’t nailed the shot yet and Forrest throws out that “I’m proud of all of you” line. In the moment, I didn’t see how funny it was. I was just like, “Why did he ruin the shot?” But it’s amazing.

Filmmaker: You like collaborative “A Film By” credits for your films, so there’s a mirror between what your working practices are and what happens in the movie.

Goldhaber: [To] make it in 18 months, there were a lot of people, a lot of delegation. There’s a reason it’s “A Film By” credit for four.

Filmmaker: Do you feel like you’ve gotten better at delegation? You seem really hands on.

Goldhaber: Better. I have work to do. It’s difficult because I was wearing too many hats on this movie, but hats I had to wear. Because the relationships with the financiers grew out of relationships that me and Ariela and Isa built, those relationships were on us to caretake while we were busy making the movie and doing all this stuff, and that’s complicated. But, in other ways, there are ways I’ve gotten a lot better at delegation. There’s other places where I need to be less precious about controlling stuff. The shape of the movie is Dan’s.

Filmmaker: In terms of the rhythms of the flashbacks and going into those?

Goldhaber: No, that did not deviate from the script at all. Most of our oners were 50, 100 percent longer than they are in the movie. Dan’s first assembly carved meaning out of a lot of footage that I did not think was there when I was shooting. He really found the movie. And it was funny, because Dan does this thing whenever he’s starting a movie. We’re two weeks into editing, he calls me and he’s like, “I don’t know how to edit a movie. What am I doing? Nothing’s going well. I don’t know how to make any decisions.” This has happened enough times now that I can be like, “Dan, this has happened. Remember? Just start cutting.” He’s like, “I don’t want to step on your toes. I don’t know the intentionality of how half of this stuff was shot. These tracking shots are way too long and I don’t know what to do with it. I’m assembling stuff, but it’s not making any sense.” And I was like, “Treat it like a doc. Pretend that you got all of this footage and there’s no screenplay.”

Filmmaker: Were the tracking shots big Gus Van Sant shots or something?

Goldhaber: I mean, they’re in the movie still. There’s really long tracking shots.

Filmmaker: Trace elements, but they’re not three minutes or something.

Goldhaber: But they are. Because I had very little time, I would shoot multiple moving masters of every scene, then be like, “We’re going to figure it out.” I’m tracking eight people for a lot of these action setpieces. How am I going to shoot that any other way with the time that I have? The problem is, if I started shooting very decisive coverage, which is partially what I had planned, I would run out of time in the day, because there wasn’t time to do it. We were also shooting in the middle of the desert. Everything was taking three times longer than we thought it would, we had no daylight to play with, I had seven-hour shooting days. At a certain point you start being like, “Here’s the action. We’re going to cover it from two, three angles, then we’re going to move on.” Dan gets that and he’s like, “What do I do with this?” So, I think it was very helpful for him to treat it like a doc. Don’t worry about the script, the beats; don’t worry about getting the whole thing in there. Find what speaks to you and we’ll go from there. Even then, his first assembly was two hours and 18 minutes, and that was without the pickups, which are two minutes of the movie.

Filmmaker: When you’re doing the multiple masters, how does that work?

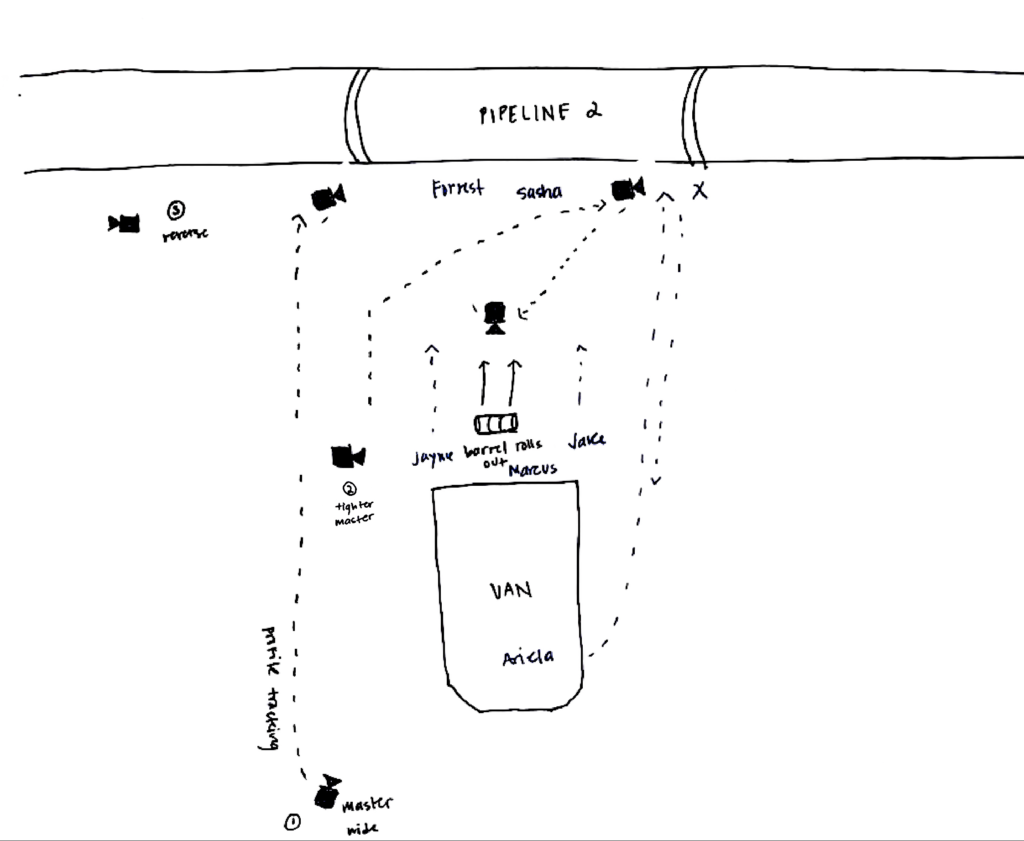

Goldhaber: I can give you an example. When they arrive at pipeline two, the aboveground pipeline, you can see the starting points for the two multiple masters. There’s the one where we push into the car. The way that goes, she drives up and the car backs up into frame. We cut to a push-in shot as people are getting out of the car and come back to Xochi walking up to the pipeline, then have a reverse shot down the pipeline. She walks back to the car, then we cut to Forrest and Sasha starting to get the straps ready for the pipeline, then follow Xochi up to the pipeline. She touches the pipeline and comes back to the car, then we’re there while they get the barrel out of the car and start rolling it towards the pipeline. The other camera starts here: the van barely backs into frame, Xochi still goes up to the pipeline, but I think that there’s some part of the shot that turned and was looking at the people in the car. Xochi comes back from the pipeline while this camera is following as they get the barrel out of the back of the car.

Filmmaker: I can almost see it. I’m going to try so hard to write that out.

Goldhaber: I could diagram it for you.

Actually, you’ll love this. The coverage was so complicated, because there were eight moving people in this really complicated action. Tehillah and I, we’re both pretty good on our feet, but it was getting onerous for everybody else because we were literally just improvising. I stopped even bringing the shot list at a certain point because it was useless because we’d get to set and something would be wrong, like somebody would’ve parked a truck where they shouldn’t have and I would just have to throw it out. Or, the cast would have ideas about how they wanted to move the barrel. There’s eight cast members in a lot of these group scenes. Immediately, things are going to change. Or I’m like, “String up the barrel this way” and they’re like, “That feels dumb,” or our stunt guy is like, “That’s not actually how you would do that.” Then we’d have to change it again. And at a certain point we were like, “We know what we want, we’ll figure it out when we get there.” So, Tehillah had the genius idea—I’m going to do this every time from now on—of buying a little mini whiteboard and strapping it around her neck. She would diagram out the scene on the whiteboard like a football diagram while I was blocking it based on whatever was going on, whatever the actors wanted to do. She would draw her camera placements onto the white board, then walk up to me and be like, “We’re going to do two cameras here, two here. Setup one, setup two, setup three, setup four.” And I’d be like, “Uh, sure. Sounds good!”

Actually, you’ll love this. The coverage was so complicated, because there were eight moving people in this really complicated action. Tehillah and I, we’re both pretty good on our feet, but it was getting onerous for everybody else because we were literally just improvising. I stopped even bringing the shot list at a certain point because it was useless because we’d get to set and something would be wrong, like somebody would’ve parked a truck where they shouldn’t have and I would just have to throw it out. Or, the cast would have ideas about how they wanted to move the barrel. There’s eight cast members in a lot of these group scenes. Immediately, things are going to change. Or I’m like, “String up the barrel this way” and they’re like, “That feels dumb,” or our stunt guy is like, “That’s not actually how you would do that.” Then we’d have to change it again. And at a certain point we were like, “We know what we want, we’ll figure it out when we get there.” So, Tehillah had the genius idea—I’m going to do this every time from now on—of buying a little mini whiteboard and strapping it around her neck. She would diagram out the scene on the whiteboard like a football diagram while I was blocking it based on whatever was going on, whatever the actors wanted to do. She would draw her camera placements onto the white board, then walk up to me and be like, “We’re going to do two cameras here, two here. Setup one, setup two, setup three, setup four.” And I’d be like, “Uh, sure. Sounds good!”

Filmmaker: This goes back to the delegation and collaboration we were talking about earlier.

Goldhaber: Jordan’s getting his PhD at Duke in literary theory and has been a part of my creative practice since I started making work professionally, literally every project I’ve worked on. He was a story editor on Cam, and we were actually writing a different movie when he recommended this book to me for that movie. This is a smaller version of that other film—that’s, like, a $30 million movie.

One thing that I think is really, really crazy about what Ariela did contribute to the movie, and something that I’m very grateful for, is I think that there is a generational component to what the movie is talking about. is a slight difference: she’s 24, 25, I’m 30. There’s a little bit of a difference even just in that gap. The younger people are, the more despair there is that there is any future at all. Ariela really brought to the film not just a political conscience and a way to breathe life into these ideas through characters, but also a real understanding and command over a way to generationally represent Gen Z in a way that is authentic. Something else that I’m really proud of about this movie is, I think that it feels very young and of the moment, but I don’t think it ever falls into the trap where you feel like it’s winking at the audience about that. It doesn’t feel like we watched TikTok for a month, then decided that we knew how teens talked.

Filmmaker: Any closing thoughts? We have to stop.

Goldhaber: No. I’m just waiting for your Letterboxd rating.