Back to selection

Back to selection

Karen Lamassonne on the Grupo de Cali, Luis Ospina and Pornomiseria

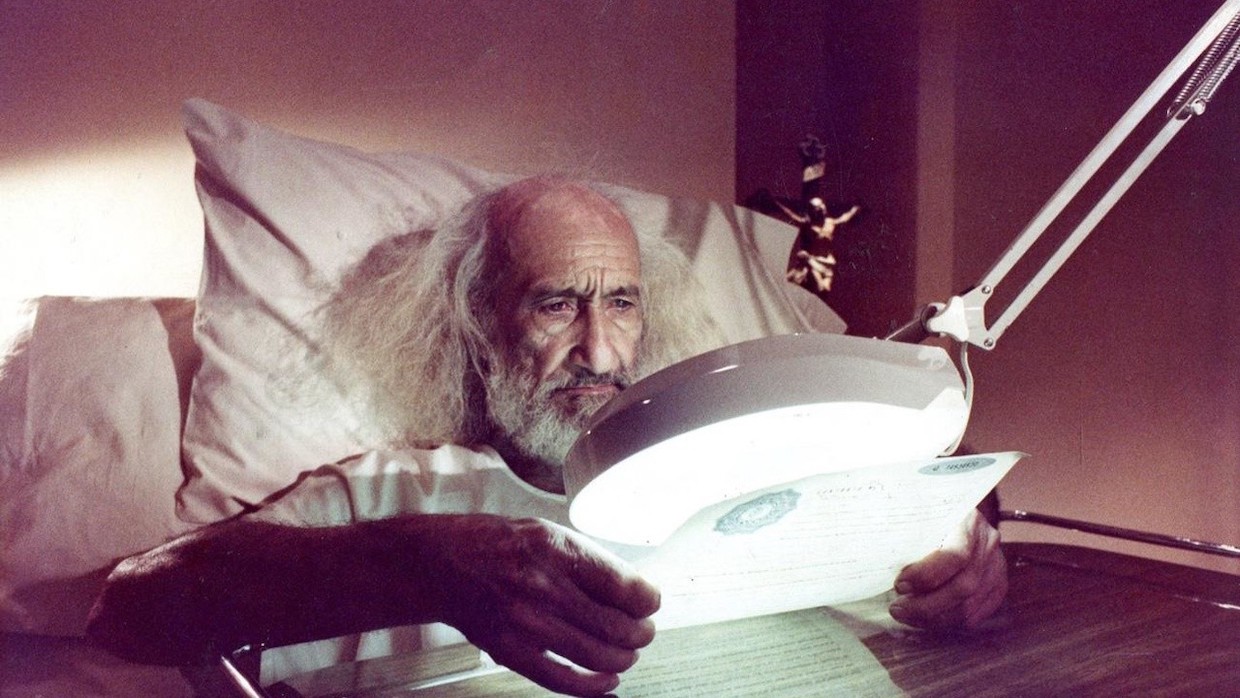

Pura Sangre

Pura Sangre Currently on view at the Swiss Institute, multidisciplinary artist Karen Lamassonne’s exhibition “Ruido / Noise” is one of the season’s essential gallery shows. In addition to a life-spanning survey of paintings, photography and sculpture by the Colombian-American artist, the show details Lamassonne’s work as an art director, perhaps most famously on Luis Ospina’s pitch-black 1982 vampire parable Pura Sangre (Pure Blood). Lamassonne was a key figure in the storied Grupo de Cali, a posse of artists, writers and filmmakers based in the city of same name, notorious both for their hard-partying lifestyle and their bottomless appetite for the macabre. Ospina and his best friend Carlos Mayolo are known internationally for carrying the magic-realist torch from literature into cinema via the hybrid genre known as Gótico tropical, but recognition has been slow coming in American repertory film culture.

Hopefully “Ruido/Noise” changes that; in conjunction with Lamassonne’s career survey, Anthology Film Archives has hosted two adjacent retrospectives. The first ran last September, and included Lamassonne’s work on a variety of rare Colombian films, while the second series honored the films of Ospina specifically. It was a tremendous pleasure to meet Lamassonne in the East Village for a wide-ranging discussion of her work—which, inevitably, meant digging into the history of the underground Grupo as well.

Filmmaker: Can you give me a quick sketch of your background—where you were, at what age, and how did it affect your development as an artist?

Lamassonne: My mother was Colombian and my father was Argentine. I was born in 1954 in Long Island. When I was three, we moved back to Colombia. We moved back to New York when I was seven, which is when I learned English, really. I really remember those very early years of my life, in Colombia‚those are really intense memories, a fantasy. I loved it. Very close contact with nature, and all this light—the tropics. Then we arrive in New York, it’s winter, it’s dark and it’s another language. I lived here all the ’60s. Summer of ’69 I moved to Los Altos Hills, in California, lived there until ‘71, I graduated high school and moved back to Colombia in ‘72. My sister had already been living in Colombia, she started introducing me to all these interesting people, and I began to draw and paint.I had been a very poor student in school. I was never going to get into college—but I was already making art. I had really prepared myself to be that artist.

Filmmaker: How long has it been since your last fine art show in the US?

Lamassonne: I’ve never really shown in the US, not like this. It’s my first show in New York. I participated in a group show back in the 90s but it was a very short thing. For me this is major. I was also in the “Radical Women” show at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, later at the Brooklyn Museum and the Pinacoteca in Sao Paolo. We were 150 women, in total. Since 2016 I’ve been doing a lot more shows. This show, “Ruido/Noise,” is fabulous because it allows me to show what I’ve been continuing to do, all the way up to the present.

Filmmaker: Tell me how you entered the orbit of the Grupo de Cali?

Lamassonne: My first show was in Bogotá, in 1974. I started early in my career as an artist: just meeting friends and people who were in different mediums—etching, people that were doing a lot of publicity, filming commercials, etc. The Cali Group, Luis and Mayolo, would come to Bogotá and get these friends working in publicity shooting commercials to give them pieces of left-over virgin film stock, lending them cameras, because everything was very expensive.

Filmmaker: Internationally, Luis’ most famous work might still be the short film Agarrando Pueblo, which is known in English as The Vampires of Poverty. The direct translation is closer to The Tricking of the People. I interpreted this as an assault on the social-realist “surcharge films” made with government financing.

Lamassonne: I don’t know. There were a lot of filmmakers from South America and Europe who would come into a slum, film some poor people, edit that, put a voice-over on it, give the images a completely different context or whatever context they wanted to give it—that is what Ospina and Mayolo termed pornomiseria, or poverty porn. Agarrando Pueblo denounces that whole realm. I was living with Luis in Paris when he was editing that film. We took it to a couple festivals, including the documentary shorts program in Oberhausen. It wasn’t officially included but Luis knew the guy who organized it, and he thought Agarrando Pueblo was interesting, so we had like a closed session of the film. I recall a lof of the filmmakers there were the makers of those kinds of movies. They felt insulted, attacked—because it was attacking them! There was one filmmaker, I think his name was Jorge Cedrón, from Argentina—he stayed, and we all became friends. He really got into the movie and then after that the movie really took off. But it wasn’t that people were creating films for a specific government office or agency—people were just making those kinds of films, that genre was taking off.

Filmmaker: I was floored to learn the phrase pornomiseria was coined in the 1970s, because I tend to associate “poverty porn” with mediocre documentaries and large-format photography of abandoned Rust Belt factories in the Great Recession, that kind of thing.

Lamassonne: It is amazing Luis made this film in 1977. It’s always of the time, it doesn’t age. I’ll just never forget when I saw that movie: when Luis Alfonso Antonio is braying at the camera, when he takes the film into his hands and begins to rip it up, I felt something going through my body.

Filmmaker: But you did not work on Agarrando Pueblo.

Lamassonne: No. Luis gives me thanks at the end because I donated some artwork—they had friends contributing money so they could finance the film. This is when Luis and I, as we say, started to “bother” each other. There was already a very deep friendship.

Filmmaker: Anthology has done two series—one focusing on your work as art director for Ospina and others, and another monographic retrospective, in memoriam for Ospina. My first exposure to Luis Ospina was his three-hour documentary It All Started at the End, about the history of the Grupo de Cali. Which is to say, I saw clips from his films before I saw the films themselves.

Lamassonne: I chose to present It All Started at the End on the 27th, three years to the day that Luis died. For me it was pretty cosmic, because I didn’t program the series or plan it that way. What we’re showing in the Ospina series are films that I worked on, but there’s many more, so we agreed to select five. I picked three of Ospina´s (Pura Sangre, It All Started at the End and Searching for Maria) plus one of Carlos Mayolo’s films (Carne de tu Carne), because I’m an actor in that one and edited it as well. We also tried to find a copy of Valeria, by Oscar Ocampo, another filmmaker from Cali; I acted, edited and did the art direction for that one. It’s one of my favorite films but it just hasn’t gotten a lot of attention, so there’s just a few messed up 16mm prints in Colombia. It was financed by the government but they only put money into certain priority projects.

Filmmaker: Ocampo was part of your scene?

Lamassonne: Yes. He’s younger than the rest of us, and he’s continued his career. Luis considered him part of the group. And I also worked on films in Bogotá, with people who had nothing to do with the Group—because we had a kind of stigma, you know, we were the partiers, for all the Bogotáno people we were kind of…

Filmmaker: Rivals?

Lamassonne: Well, there’s always rivalries, in all genres of anything that you have artistic creations. It’s kind of like East Coast/West Coast here. In Bogotá it’s cold, you’re up in the mountains, but Cali is really warm, there’s a river going thru the city, so it’s a completely different outlook. I also asked [Anthology Film Archives curator] Jed [Rapfogel] to get a film which I saw last night—a remastered print of María Cano, by a female filmmaker, Camila Loboguerrero, another film where I did the art direction. It was really awesome to see it, because I had not seen it since we made it in the ’80s, and I did a lot of work, because it takes place in both the 1920s and the 1960s. It’s about a very specific time and place, Medellín in the 20s, and it’s about a woman who creates all of the unions, and she fights for the workers. I really got into the colors and the wallpaper. I designed wallpaper for it, had to get into the aging of all of these spaces too.

Filmmaker: I love the short film Cali, de Pelicula. It has a lot of footage which looks commercial, maybe like it came from a travel agency?

Lamassonne: No, this was all original footage of Mayolo and Ospina. Film stock was very expensive, so sometimes friends that worked filming commercials would save them short pieces of virgin film that they had left in their canisters, material they were just gonna throw away. In any case, I did have some friends in Bogotá who were friends with the caleños, because they had this fame—tough, edgy, party people.

So, I met Luis through one of those friends in Bogotá, and we had an incredible chemistry and a lot of things in common. He had spent part of his high school years on the East Coast, he studied film at UCLA, so we had lived in the United States many of the same years, watching the same television programs and movies, influenced by a lot of the humor and things that were happening in this culture. We were also very Colombian—my father is from Argentina but he lived many years in Colombia—so all of that really brought us together. I would go to Cali while keeping my little house in Bogotá, and I actually did a show in 1975 before I met Luis. I went to Cali with these paintings, to a gallery—I didn’t know any of them but met an art curator named Miguel González, who was part of Ciudad Solar. I loved Cali—visiting from Bogotá I was like, “Whoa, this city is amazing!”

I did a few shows in Hamburg and Berlin, while Luis was in Paris editing Agarrando Pueblo. We lived there for over a year, moved back in 1979 or 1980, and he started working on the script for Pura Sangre. I came back and did an exhibit about bathrooms—some of the paintings are here. That show was taken down three days after it opened, because it was hanging in a multi-purpose room, and there were an executive giving a conference. I guess people were paying more attention to the paintings than to him—“I cannot continue with these obscenities hanging on the walls!”—he said and had the whole show taken down. So,I took the show to Bogotá, to Medellín. I also worked on a film, my first doing art direction, right around when I was meeting Luis.

Filmmaker: What film was that?

Lamassonne: El Ultimo Cliente, directed by Miguel Torres, who did theater. It’s two actors on one set, which was a secondhand shop with all these clothes and things. Luis knew of that project, so when he came back, and started doing Pura Sangre, he asked me to do the art direction, the storyboard, and we worked on the technical script. I became really empapada with the project, which is something we say in Spanish that means “soaked”—I was really drenched, or I had all that information in myself.

Filmmaker: Do you know Jairo Pinilla? I showed two of his films, Triangulo de Oro and Extraña Regresion. Of course I’d like to show more, but the only copies out there on the dark-cinephile-web are VHS transfers that look like they were run over by a truck.

Lamassonne: I’ve always loved his films. I would joke to Luis and to Mayolo that Pinilla was my favorite Colombian filmmaker, and they would get pissed off (laughs). His movies were just really crazy, with amazing themes—horror, science fiction, super-wild. I had a very dear friend at the Cinemateca Bogotá, Enrique Ortiga, he also worked at the MoMA. We would get really stoned for a Pinilla film and just laugh through the entire movie. They were so entertaining—nothing deep. They always deal with myths or legends that exist only in Colombia. They enter the gotico tropical realm, or magic realism if you like.

Filmmaker: Was the plan to continue working as a fine artist but to do films to make money? Or to become a professional art director?

Lamassonne: The former. I loved my solitary work. For me it was wonderful doing the storyboards or whatever, because it was also solitary work, just two people. It’s not that shooting was incredibly difficult for me, but it required working with a lot of people and a lot of ingredients. But I started doing a lot of work in photography and film, of course, influenced all of that. Then somebody else would make another film and I wouldn’t do art direction but I would edit, or act, like in Carne De Tu Carne, the next feature film that we did. With Luis there were always smaller projects, especially when he started working in video—he always wanted to collaborate and for me it was a pleasure, so I would always do art direction or specific drawings or art things that he needed. At the same time I was doing shows, other people would hire us—I was making money, working all these different jobs, because it would pay better than just painting and not selling my work. So I could do a film for six months, then live for six months and produce some of my work without having to work.

Filmmaker: Did you draw a hard separation between—for lack of better phrases—“paid” and “creative” work? This is a different time/place, of course, but it’s super common for artists to take, uh, less-prestigious assignments to stay alive.

Lamassonne: Well, the government film office was financing films. So, people did have budgets, and I was becoming known for my art direction work. Camila Loboguerrero hired me for María Cano because she believed I could do a good job. We did a ton of research and investigation and I loved doing that. I’m very social, so filmmaking was a job I loved. I enjoyed working with other female filmmakers in Bogotá. We would go to the Cartagena Film Festival every year. Victor Nieto was the founder, and his son. Victor Nieto Jr., took the reins at one point. He was our age—he would go to Europe and find films that were of more interest to us: Warhol, Fassbinder, etc. When he brought Querelle, the producer was Dieter Schidor, so Fassbinder and Dieter and his entourage came to Colombia. Dieter and I became very good friends, we actually had an incredible night—Sam Green was an American, a very wealthy man with a big house in Cartagena. I believe he sold antiques. Greta Garbo, Yoko Ono—they had been in this house. All this is cited in Kalt in Kolumbien; his house was used as the mansion in the film. Dieter and I had dinner there one night; Sam invited us, with Luis, a sit-down dinner for eight with Garcia Marquez also. That’s when we decided to make a film in Cartagena which ended up being Kalt in Kolumbien. Projects like that would surface. Werner Herzog made Cobra Verde in Colombia. We worked very hard on that one, as detailed in It All Started at the End. But we were not included in the credits.

Filmmaker: Why not?

Lamassonne: There was an unfortunate incident that happened, in Cali, which is fine. But we worked on the film—Sandro Romero, Miguel Gonzalez, Mayolo also. They got their credits, but us in Cali did not. It was an amazing experience, working with Klaus Kinski— he was just huger than life, an incredible character, a genius, but everything was about him. He was very paranoid. So, if he wasn’t the center of attention, if somebody was taking attention away from him, he would make a big scene screaming.

Filmmaker: I’m sorry – what was the “unfortunate incident”? (Are you allowed to tell me?)

Lamassonne: I think I can say it. We had to get a room for Kinski to live in, and there’s a very tall building—La Torre de Cali, the hugest tower in the city. He got the penthouse and an incredible car. When he got there in Cali, on the mountain, he saw there were three crosses on the mountain, and he wanted us to remove them. He was that crazy. We worked sometimes with mafiosos —they had access to things other people didn’t. We would rent from them, they helped with accommodations. We did the production, basically, for the whole entourage—coming, filming, leaving. We had to find 300 sugar cane cutters in a field for Herzog—we did a lot of different things during a short span of production. Then everybody starts leaving. Sandro and Miguel and I are in my apartment and Miguel says, “They’re leaving. I’ve heard stories of Germans coming into town and ripping everybody off, not paying anybody.” Well, we were owed a lot of money, and we also owed money—some of it—to the mafiosos. They had rented us cars, apartments, helped with the hotels. We were like the location managers for the whole production, the art direction, in both Cali and in the [Valle de Cauca]. There was a producer from Cartagena, but he was always avoiding us, so… Miguel sent the police to the airport and they stopped Herzog’s [half-]brother, [producer] Lucki Stipetić. He was leaving with our money! He had a briefcase full of American dollars. He was taken to jail (laughs). A very good friend of ours, Pedro Alcántara Herrán, a senator and a very well-known artist too. We called him in the middle of the night: “We didn’t want him to go to jail—we just want to get paid!” They paid us and then they left. Lucki was so pissed off, because he was on his way to Brazil to shoot other scenes—I guess he was the last one left in Colombia. Sandro wrote a very funny article about this whole experience, but they did not credit us in the finished film.

Filmmaker: As revenge.

Lamassonne: Yeah. Mayolo received credit, as did other people who worked in Colombia. Sandro and I had been unsure if we should do this to them or not—and I’m kind of glad that we did, because we never would have gotten the money if we hadn’t done that. And those mafiosos were knocking on our door. You don’t want those people knocking at your door.

Filmmaker: Anthology showed an incredibly rare 16mm print of Dieter Schidor’s Kalt in Kolumbien (Cold in Colombia), featuring yourself and Gary Indiana. This film is about Germans in Colombia. There are references to concentration camps, as well as the drug trade. One of the main characters is a German journalist doing a story on cocaine trafficking. (I laughed when he told Schidor’s character and he replied, “How original!”)

Lamassonne: Dieter is just so funny. He’s cracking jokes the whole time, making these really dark commentaries. I wasn’t really sure about the whole story of Kalt in Kolumbien—I might even have that script that they sent me—but the movie is a combination of different things. He was writing a story about concentration camps, but a lot of this is just fantasies Dieter had from visiting Columbia. This was during the really bad mafia times. The film is very German.

Filmmaker: Help me to better understand these relationships. There are drugs flying around, there’s political violence, you’re in league to some degree with the cartels…

Lamassonne: Well, the mafia was buying artwork. And they messed up the way art was sold, because then they inflated all the prices. The artists would want those prices, but they weren’t real. The mafiosos had the money, they would just spend whatever. So, the art dealers were selling it for more money than was due. This meant artists were (briefly) able to live off of their work, which was unheard of. So the mafia offered that. At the same time, they were pumping drugs into the market. There was a lot of violence, a lot of people were getting killed because they had all kinds of small gangs, big gangs, hired assassins to kill specific people, to steal money from them, kidnap them. And there were paramilitaries beginning to form. In the middle of the 80s, guerillas [began] getting mixed up with the mafia because they were growing coca, but the guerillas were in the jungle where coca was grown, some of them were under the protection of the mafiosos. It got very complex. Cali was different from Medellín: Pablo Escobar came from a very poor part of Medellín, whereas in Cali the drug trade involved, for example, bankers. We were living in a fantasy world: we continued to work, the government provided us money to make our films. We lived off of that, and made our real money from the mafia. I’m sure they were involved in ways I wasn’t aware of at the time. But there was a lot of violence. The Palace of Justice was bombed, there were huge campaigns of attacks on the guerrilla groups.

Filmmaker: Did you, or Luis, or any of the Grupo, ever have this dream of “going Hollywood”?

Lamassonne: I wasn’t a movie director like Luis, or Mayolo, but I was very involved in all of this movement. There was a desire to work with other directors for sure. Luis did leave Colombia; his film The Supreme Uneasiness: Incessant Portrait of Fernando Vallejo was produced in Mexico. We were very friendly with Barbet Schroeder, who opened a lot of doors for us. Luis also had friends in South America. But the dream, the ambition, was to take these films outside of Colombia, outside of Latin America. It was very difficult to make back the money for the government, so we would have these debts to these government agencies. We were a very tight-knit group, you know, with a specific way of doing things. I remember a friend who came down and had been working on films in the States. Hhe came down and had the American mentality of how to do things. He couldn’t adapt to the way we did things. “Let’s just get the gelatin filter for this light”—there was no gelatin filter.You had to invent things. And it was easier for Luis to make films in Colombia because there were all kinds of grants he could apply for.

Filmmaker: If I’m not mistaken, the organization that financed Pura Sangre was FOCINE.

Lamassonne: That’s just one. There were all kinds of organizations having screenwriting contests, and if your script won then you got help producing it, things like that. Luis was always applying to them; he got a lot of money from that! He would partially finance himself, and for the rest, do a coproduction with friends or other countries. His 2000 film noir Soplo de Vida (Breath of Life) is one example.

Filmmaker: It All Started at the End includes footage from the press conference after he premiered Pura Sangre. It seems like a pretty controversial moment, and I believe someone also mentions he had been up all night beforehand.

Lamassonne: So, I can’t be objective about Pura Sangre. I did the storyboards, I have this very tight bond with it. I don’t see its characters as horrible people, necessarily, but the story is indeed horrible. Especially the nurse: she’s just such an awful person, the things that they do, kidnapping and killing children… The movie is not bloody, because the blood is all contained in hypodermic needles, in bags. It was also a film financed by the government, so in a way it’s a reflection of them, an image they are exporting of Colombia, and it’s not great. But a lot of the film is based on incidents that really happened, even though it’s fiction. There was a lot of espectativas: “What is this movie gonna be?” “What have people heard?”

Filmmaker: Even showing it in 2016, I found people had objections. Because they presume a “vampire movie” has to be fun, campy, postmodern…

Lamassonne: It is so much more real than a vampire film—but it’s also the traditional story of the vampire, who sucks the blood of the poor people. It’s also very Colombian. If an Argentine sees it, they’ll know it’s Colombian. And for a lot of people that was terrible. The story is especially awful for people who have children. I didn’t have children then; I have a son now. I didn’t show him Pura Sangre until he had graduated high school, and he tells me he thought that was good.

We shot the film, edited it, did final mix and color timing here in New York—the labs in Colombia were not very good. One thing Luis wanted: he wanted it to look and sound really good. Because it had always been very challenging for them to do good, direct sound on a competitive, professional level. Which is why he hired Ramon Suarez, who is Cuban, to do photography, and Phil Perle, a New Yorker, did the sound. So, technically it’s very good. You can hear everything and it looked beautiful. People had a lot of expectations to see this film. Literally, we made the print and took it straight to Cartagena, to the festival; we didn’t even go home. The print was still warm from the oven—nobody had seen this movie. The film was a mystery, and it was the first film FOCINE produced. It was like the bad, evil baby – the devil. And it was the opening film of the festival, really a big deal. And we hadn’t slept. We had partied all night.

Filmmaker: Outside the Grupo de Cali, did the film have much Colombian support?

Lamassonne: Not a lot of people. And the ticket to go see a movie was so cheap, you had to bring in the same number of spectators as E.T. to make money, to break even. And you can’t. And FOCINE was in diapers. They didn’t realize they needed to have a kind of distribution setup. Nothing was set up —we tried to do as much publicity as we could, posters on the street and the walls, handing fliers to people. I enjoyed it, but I know for Luis it was very stressful. He owed all this money. I think a lot of it was pardoned in the end, but FOCINE owned, and kept, the film. Because there was no way he would have been able to pay back all that money.

Filmmaker: I organized a retrospective of Luis’ films in 2016, but I also wanted to show Carlos Mayolo’s two features, Carne de tu Carne and Mansion de Araucaima. It was too expensive; we couldn’t reach a deal with the state agency controlling the restorations.

Lamassonne: There was recently a forum in Bogotá precisely about these prices, these obstacles that filmmakers have in Colombia. There was a representative of ProImagenes there, dodging all kinds of arrows, being accused of not supporting—of actually going against—Colombian filmmakers. Of course they need money to survive, too. But they also create problems where they shouldn’t.

Filmmaker: Generally speaking, within “underground” culture, where does the Grupo de Cali fit? At first I thought they were a bit like hippies; in Luis’ documentary about his late friend the writer Andrés Caicedo, someone uses the phrase nadaismo.

Lamassonne: I would compare them more to punks. The nadaistas were a real movement but more like poets, writers, and from a different moment. The Cali Group was also unique because they had this fascination with the gothic, with gore, with death, with violence. Andrés Caicedo was really into—all of them were really into—B-movies, Roger Corman, tThis sort of look, these sorts of films. They had edgy tendencies but they weren’t hippies: they also loved drugs and the Rolling Stones.

Filmmaker: Here at the Swiss Institute, you have a furry, monster’s hand you’ve fabricated. For a moment I thought it was from a Colombian werewolf film I had not seen!

Lamassonne: It’s called “la mano peluda,” the hairy hand. It should be a movie. My first love as a little girl was Bela Lugosi. Growing up as a Latin American, there’s all these legends and stories I grew up with; my grandmother was very religious and she told us all these wild stories, always at night.

Filmmaker: I believe the basis for Pura Sangre came from stories of a serial killer during Luis’ childhood, el monstruo de los mangones, so the film splits the difference between folk and urban legend.

Lamassonne: It happened. When Luis was growing up, the dead, naked bodies of young boys would turn up in these empty lots, raped, some of them with their blood withdrawn. The myths started there, but it was really happening. And when I was little, they would say: “If you don’t go to sleep, the hairy hand is going to come get you!” I always loved creepy things. I’ve done about 15 hairy hands—all different materials, hair from me, hair from different people, all kinds of different fabrics.

Filmmaker: Earlier, you described yourself as a very social person, and filmmaking requires that. But the paintings in this show seem more solitary. Do you have a dual personality as an artist?

Lamassonne: I guess you could say so. Early on I was working on my own, although I was known to be painting while we were having parties—the fact of people being around didn’t stop me. Making films got me more integrated with people – theater, friends, sets, costumes, all that. But as a visual artist there’s always that solitary moment. My video Ruido is very solitary, but I did another one, Secretos Delicados, which involved all of my friends, so there’s that as well. Nowadays I could go either way. It’s great to always have yourself to fall back on.

Filmmaker: You must have been very young, making some of these. I’m thinking of the hyper-intimate bathroom series.

Lamassonne: The ones from 1974. Yeah, I was twenty.

Filmmaker: I think of Luis’s films as scandalizing, Pura Sangre and Agarrando Pueblo specifically… I’m wondering if some of these paintings had, or were intended to have, a similar affect.

Lamassonne: I did not consciously do things to scandalize people. To me, ever since I was young and I saw art in museums, I always saw the nude body in art. I would draw my sisters naked when I was younger. The body was always the basis of everything—it’s a reflection of who I am, no? When I got my own place, that was such happiness for me—to be on my own, come and go on my own time, work on my paintings, use mirrors to do self-portraiture. I didn’t have the money to pay a model, so I would be naked or half-dressed or whatever—I always wanted to include myself in those compositions. It was very much a process of discovering myself, being independent, sexually active, different from the women in Colombian society around me. I felt like I had different motivations. To me, being scandalized is what’s scandalizing, no? When they took down my show, I had a friend from New York visiting me. She said, “You know, Karen, this is kind of risque.” It surprised me. I did things not to scandalize, but to be satisfied. It was borne of me—in Spanish we say, “me nacía”. It flowed. But I wasn’t doing it for anyone else to think “Oh!” Now, sometimes there were invitations to erotic shows or to contribute to a book of erotic art. That’s not how I considered myself —an “erotic artist”—especially given it was a nude figure, not a sexual act. It’s like a Greek statue.

As an artist, with time, you begin to really understand what you have done, what you have become —you get better at explaining it to yourself. Which is why it was so great Luis was able to make It All Started at the End. Barbet Schroeder, a good friend, was the one to tell Luis he should make a film about the group, about Cali.

Filmmaker: Were Luis and Carlos Mayolo happy, ultimately, with the number of films they were able to produce?

Lamassonne: Cali became a city that was difficult to survive. Television opened a big venue for a lot of people in our group—a lot of people went to Bogotá to work in television, especially Mayolo. His epic series Azucar (Sugar) went on for years. He was pretty wild! But Luis was a purist. He wanted to continue making his films. He did documentaries and things that made him vibrate; he couldn’t really adapt himself to make series, although he did one for TelePacifico, Cali, Today, Tomorrow and Yesterday. One episode is included in the Anthology series. He stayed in Cali and was a professor, a teacher, and helped to develop the regional television station there. Everything was centralized in Bogotá in that moment; the ’80s is when things really start going outside of Bogotá. Luis stayed in Cali and developed that for a few years, then he left to go live in Bogotá. The late ’80s are when we began to drift apart, come back together. But we continued to have a very incredible bond.

Filmmaker: I never met Luis but we corresponded via email. I could never tell if he was bitter or happy about his career. Here in New York, I’ve met many people who were part of the downtown scene, lived like there was no tomorrow, drugs, partying, the whole bit—time goes by, they survive, but things did not pan out well after those glory days. For you, Luis, Carlos et al., was there a vision or a concept of what the future was going to be? Does this question make sense?

Lamassonne: Yes, it makes sense. I think Luis was satisfied with what he accomplished in his life. When he started getting invited to all these film festivals, it got even bigger—people were ceding him the importance he deserved as a filmmaker. He programmed films as well, he created a film festival in Cali, and he was able to do it on his terms, the way he wanted. He traveled the world, went to festivals and brought to Cali films that never would have played otherwise. That’s what he did for that city. Ever since I met him, I saw all the things he did for Cali, and for film in Colombia. The people he influenced, it’s like a whole school that came after him. There’s a legacy. I think he was very satisfied as long as he could keep going, keep producing.

Filmmaker: Which is a sign of health, in a way – instead of fixating on the past.

Lamassonne: Yes.

Filmmaker: And you—satisfied?

Lamassonne: I’ve been very lucky, but I feel like I still have more to produce, even in 2022. All of this just motivates me to do more.

“Listen, Look: The Films of Luis Ospina” is at Anthology Film Archives until October 18; “Karen Lamassonne: Ruido / Noise” is at the Swiss Institute until January 8, 2023.