Back to selection

Back to selection

Viennale 60: Curating Politically

Herbaria

Herbaria Probably as a consequence of reading Viennale 60. On Film Festivals during my long train ride back to Berlin, a few of the films I saw at this year’s Viennale became emblematic of my four days there and of the festival as a whole. Published on the occasion of the 60th anniversary, the book collects essays by and conversations between two dozen experts: current and former directors of Europe’s major fests (Cannes’ Thierry Frémaux is conspicuously absent), programmers, curators, critics and scholars, as well as one filmmaker, festival fixture Denis Côté. Spread over some 200 pages, these combine into a sprawling reflection on the politics, philosophy and current state of film festivals.

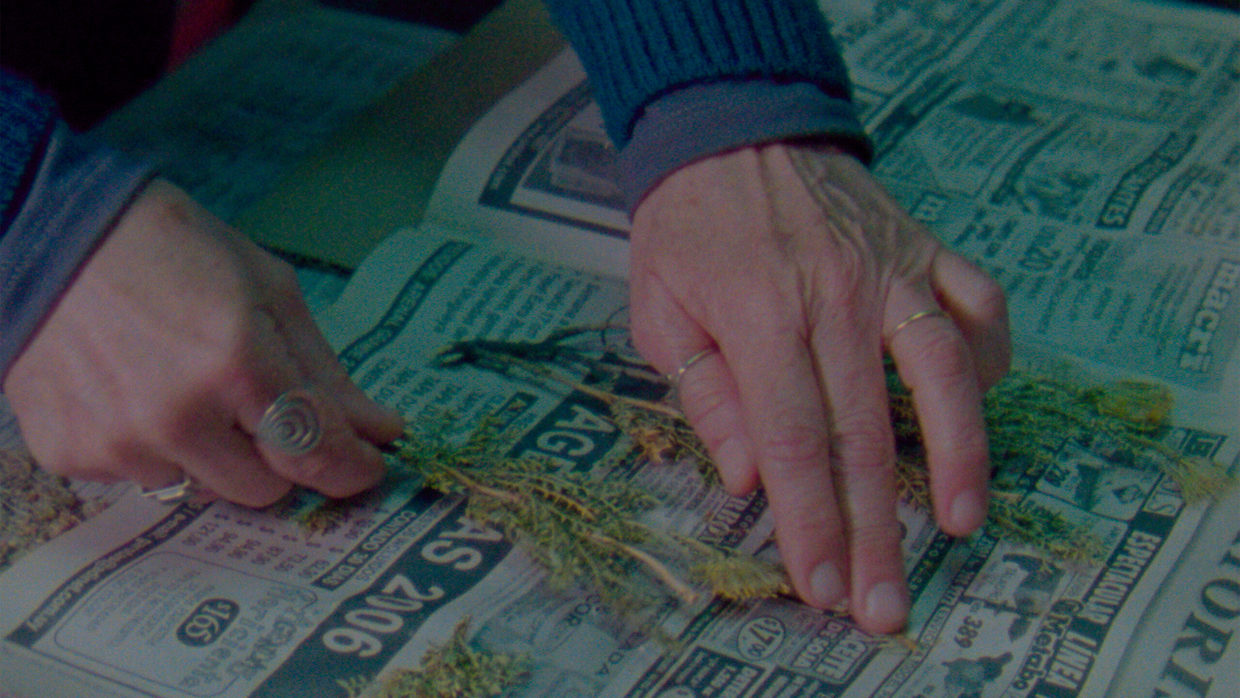

It’s the kind of inside baseball rumination salvaged from excessive navel-gazing (though there’s certainly some of that in there) by the infectious passion and stirring idealism it exudes. This quality, which Serge Daney ascribed to passeurs—those people capable of enticing others to cinema through their erudite enthusiasm—also pervades Leandro Listorti’s Herbaria. Elegantly composed from original 16mm and archival material, this poetic reimagining of a didactic documentary draws parallels between the preservation of plants and of analog film, underlining the vitality of both practices in not only maintaining a record of history but also understanding our place within it. Listorti, himself an archivist at the Cinema Museum in Buenos Aires, conveys the technical aspects of his work in affectionate detail, from the atmospheric conditions and type of boxes used to store film, to the organic composition of celluloid, to the process of digitally rescuing images on a century-old, mostly decomposed nitrate filmstrip. It’s a thoroughly romantic portrait that nonetheless situates film archiving within greater hegemonic realities pertaining to the selective preservation of memory and, by extension, the writing of history.

A related facet of these realities is confronted head-on in Arabs and Niggers, Your Neighbours, the second feature by Med Hondo, screened at the Viennale in a program dedicated to the director’s work. Hondo originally released the film in 1974, then kept reworking it until 1988, integrating feedback that he received from African migrant workers in France as an effort at participating in their struggle via cinematic means. In the formidable opening scene, a man wearing a boubou addresses the camera while standing in front of a wall covered in posters of European and American films such as Tarzan, For a Few Dollars More and Heller in Pink Tights. His caustic 20-minute monologue summarizes the history of cinema as an extension of colonialism and he brings it to a close by calling for the creation of an African cinema, at which point the film crew step into the frame and join him in ripping all the posters down.

The rest of the film comprises vignettes that function as Marxist lectures—some are literally scenes of a professor in front of a white board, others are sketches whose dialogues double as theoretical debates. These are broken up by interludes such as a moving montage of migrant living quarters scored to Catherine Le Forestier’s “Allez voir mes voisins” and a satirical Terry Gilliam-esque animation that depicts African heads of state as lackeys of Nixon and Pompidou. (The ridiculed parties in the latter segment reportedly tried to get the film banned when it was first screened in Algeria.) Although it’s all very much in the vein of French left-wing intellectualism of the time, Hondo’s articulation of such discourse is remarkable for its populism and acquires an intense emotional charge as his tone shifts over the course of the film from scathing sarcasm to sincere urgency.

Kazakh director Darezhan Omirbayev is the focus of the fourth issue of Textur, a journal published annually during the festival. Each issue sketches an overview of a notable filmmaker’s oeuvre via a multiplicity of materials, such as essays, interviews, photographs, short stories and poems. (Here, the texts are accompanied by English translations of Omirbayev’s haikus, each a potential short film: “The first line is the first shot,” Kent Jones quotes him as saying, “the second line is the second shot, and the third line is what is born from editing the first two shots: thesis, antithesis and synthesis.” One example: “Two sailors survived/A shipwreck/Already they dream of a new boat.”) Alongside the journal’s release, the Viennale screened his two latest films, the feature Poet and the 30-minute The Last Screening. Companion pieces, they thematize the disappearance of artistic expression and of a national culture in contemporary Kazakhstan; as suggested by their respective titles, one presents poetry as a synecdoche for this loss, the other cinema.

In their deadpan humor and melancholy, the films recall Aki Kaurismäki. Their style, on the other hand, is understated to the point of self-effacement, so that they regularly catch one off guard when the deceptive mundanity of the mise en scène gives way to elaborate sequences. The most extraordinary of these in both films address modern subjugation to technology, though Omirbayev favors lyricism and irony over pessimism. The Last Screening’s central set piece takes place on a bus, where every passenger is staring into their phone. As the camera approaches each in turn, looking at their screens and letting us hear through their earphones, this overly familiar image of atomization is transformed: rather than vacuously scrolling through his social media feed, a young man is rapt by a filmed conversation between Jean-Luc Godard and Fritz Lang, while a teenage girl with a violin case listens to a classical piano performance. Guided by the music, the camera follows the girl’s gaze out the window and even the ugly symbols of modernity lining the highway—enormous construction sites and shopping malls—are recast as potential sources of wonder and inspiration.

In Poet, after going on a radio show to discuss his poetry and being goaded about literature’s increasing irrelevance, the frustrated protagonist is seen wandering the electronics floor of a department store. We can still hear his conversation with the show host on the soundtrack, as if he were remembering it, but apart from the place being deserted, there is no indication of anything out of the ordinary. He then inserts a USB stick into one of the computers and suddenly the TV screens all around start broadcasting his radio interview in the same two-shot as in the previous scene. Just as we understand that this must be a dream, a wishful take-over of modern technology on behalf of art, the protagonist wakes up in a train, where we’d last seen him before the interview, which we now realize had also been part of the dream—a more vain kind of wishful thinking.

The seamless transitions between planes of reality and dream, and the resultant inability to confidently distinguish them, is a narrative approach that Omirbayev shares with Alain Guiraudie, who happens to be the focus of Textur #5 (and whose underrated Nobody’s Hero played at the Viennale). In addition to the two Textur issues, the festival accompanied each of its director retrospectives—besides Hondo, there were series dedicated to Elaine May and Ebrahim Golestan—with lengthy catalogue essays by the respective curators, who also introduced each screening. These examples make up but a portion of the exceptionally rich and varied program. Such considered curation corresponds to Alexander Horwath’s contention, in the closing text of Viennale 60, that only by integrating the strengths of a cinematheque can a festival fulfill its potential “of ‘curating politically,’ instead of just following current fashions of ‘political curation.’” Because “just as the selection and projection of any ‘old film’ can be conducted as an act for and of the present, the selection and projection of any ‘new film’ can be viewed as an act of historical consciousness.” Even acknowledging Horwath’s evident bias—he is the former director of both the Viennale and the Austrian Film Museum—his position is incontestable.

The films mentioned above bespeak this political engagement and emphasis on historical dialogue, and while they also all speak of encroachment, decline and loss, their perspective is defiant. At the end of Poet, despite needing money and enduring a humiliating confrontation with the futility of his artistic pursuits, the beat-down poet nevertheless rejects an offer to sell out. The final scene of Arabs and Niggers returns to the room from the opening, except now the walls are decorated with new posters— Rida Bhedi’s The Hyena’s Sun, Ousmane Sembène’s Ceddo, Oumarou Ganda’s The Exile, Hondo’s own West Indies—as triumphant proof of the emergence of an African cinema. In a year that brought home with particular force the vulnerability of film festivals—after Rotterdam unceremoniously fired much of its programming staff in April, Edinburgh’s 75-year-old festival was shut down in October—the Viennale embodied an analogous resistance.