Back to selection

Back to selection

Gender Biases, Ghoulish Visages and “Jazzy” Broaches: Director Lesley Manning on Ghostwatch 30 Years On

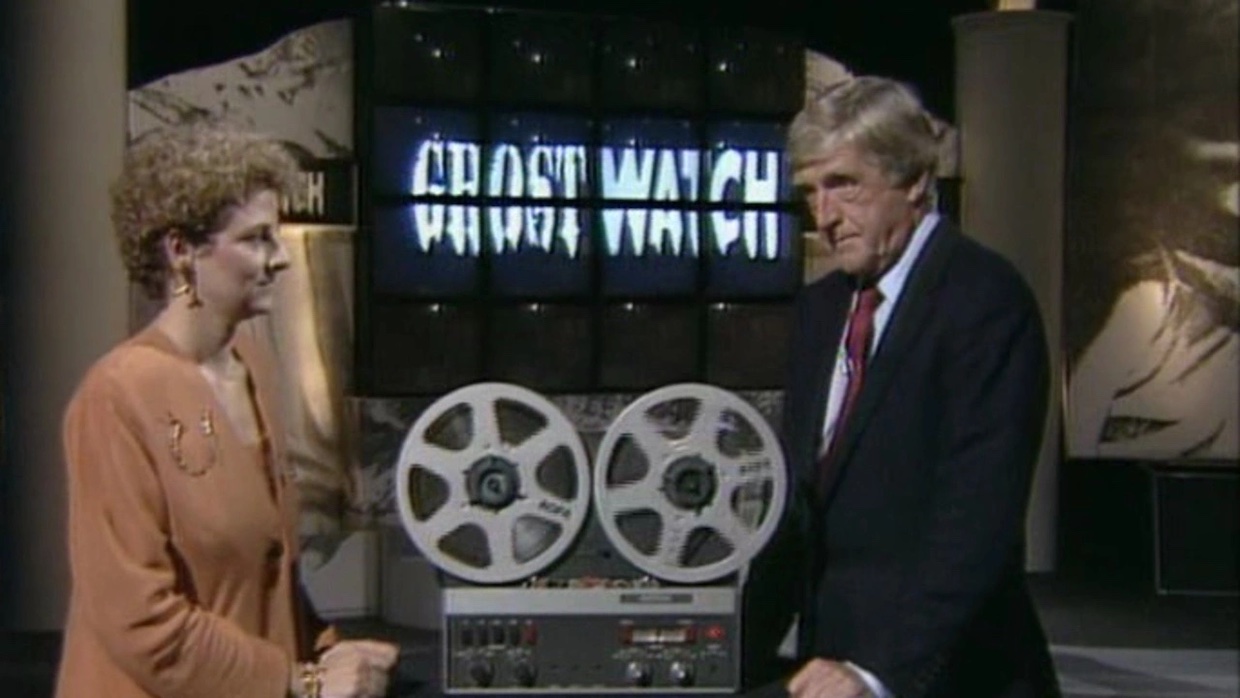

Gillian Bevan and Michael Parkinson in Ghostwatch

Gillian Bevan and Michael Parkinson in Ghostwatch On Halloween night 1992, the BBC switchboard became inundated with an estimated one million phone calls related to a now-infamous TV broadcast. Convincingly filmed as a live news report—even featuring recognizable BBC presenters Michael Parkinson, Sarah Greene and Mike “Smitty” Smith—Ghostwatch convinced a wide swath of the British populace (reportedly including Parkinson’s own mother) that a real-life possession was unfolding in front of their eyes, and that a demonic entity was being channeled through their own screens. Though programmed as part of the network’s narrative anthology series Screen One, many viewers tuned into the program after the identifiable drama banner was displayed ahead of the film’s 9:25 p.m. slot. As a result of this panic, the film was effectively banned in the U.K. for 10 years, with the first physical release of the film only emerging in 2002.

The film centers on the Early family living on fictitious Foxhill Drive in the suburb of Northolt, Greater London. Mother Pamela (Brid Brennan) and her young daughters Suzanne (Michelle Wesson) and Kim (Cherise Wesson) believe that their home is under siege by a violent entity. They enlist the help of the BBC to help prove their claims aren’t a mere hoax, with Sarah Greene reporting “live” on-the-ground from Foxhill Drive. They frequently exchange dialogue with Michael Parkinson and Smitty, who follow the story from the TV studio. By Parkinson’s side for the evening is parapsychologist Dr. Pascoe (Gillian Bevan), a firm believer in the paranormal who’s been investigating the Early’s claims for the past few months, attempting to get to the bottom of why the poltergeist “Pipes” (named so by Pamela, who initially insisted to her children that his presence was merely the work of rusty pipes groaning in the walls) has marked the Early girls for possession. What makes Ghostwatch so chilling, though, is the conceit that “viewers” keep calling the studio to report that they’re seeing the ghostly visage of Pipes in the fuzzy, blackened corners of their TV screens—when you begin to look closely, he truly does manifest in the background of otherwise ordinary shots. To this day, there’s no official confirmation as to how many times he really appears in the film.

Written by Stephen Volk and directed by Lesley Manning, Ghostwatch was meticulously scripted and filmed weeks ahead of its TV debut, which only aired on Halloween night by happenstance. Yet it also incorporates an uncanny reality that perfectly mimics an emerging broadcast language. In a 2011 post entitled “Ghosts in the Living Room” for his BBC blog The Medium and the Message, BBC documentarian/video essayist Adam Curtis wrote that Ghostwatch “demonstrated the truth about modern television—that we all know that increasingly the line between fiction and non-fiction is blurred on TV. But far from making us distrust television this actually makes it more powerful. It possesses our imagination more powerfully precisely because we don’t know what is real and what is not.”

With a long-awaited 30th anniversary Blu-ray release from 101 Pictures having been released this past week, Ghostwatch is finally accessible as a form of physical media for U.S. audiences. Shortly before the anticipated collector’s edition hit Amazon (which also means it’s now available to rent/buy via Prime Video), Filmmaker spoke to Manning, who offered insights on the film’s intricate shoot, the film world’s deeply-entrenched gender biases and Dr. Pascoe’s then-outrageous costume choice.

Filmmaker: What makes this film so effectively illusory is the fact that it pulls from, and in a way recreates, images and artifacts from real-life possession and poltergeist cases. Surely a huge inspiration for Ghostwatch is the Enfield Poltergeist case from the ’70s, similarly located in a London suburb. In fact, the photo that Dr. Pascoe shows the audience of Suzanne and Kim seemingly “floating” in their bedroom is itself a wonderful recreation of that iconic photo from Enfield. Were there any other visual or narrative supernatural references you mined from for Ghostwatch?

Manning: The Enfield case was a big influence, that’s for sure. Steven [Volk] might say something different, but I actually did all of my research on how to tell this story through—and make it look like—live TV. My horror research came from A Nightmare on Elm Street, because I was looking at horror language and what frightens me. You know, the camera angles and what you see versus what you don’t see.

We came from the film department [of the BBC], but I insisted that we shoot on tape, because we needed to get it very similar to the look of TV, which really upset the film department enormously. But it was great for me, because I could use all of the correct cameras. We shot it over a four week period. Some people think we shot it over one night, but we didn’t; we shot it on a film schedule. But Steven and I spent a long time looking at how TV was being presented, specifically those sorts of [news] programs, and how to use that language effectively for horror.

Filmmaker: Yeah, tell me more about the different cameras and technologies utilized in the film. There are static cameras placed within the Early’s home, cameramen running around with cumbersome rigs, thermal imaging, studio cameras. It is, in a way, also a fascinating document of ’90s-era image capturing technology. So here’s a double-pronged question: how did you navigate using all of these different cameras, and how do they capture this particular era of TV imagery?

Manning: I’ll answer the second question first. We researched the [visual] language of the day, so that’s why I think it captures the ’90s. There was a different feel there, and it was emerging and changing already. I mean, I was shocked when the news first had music on it. During the Gulf War, it used to be that nobody ever did that sort of [real-time] coverage before. We also had a series [in Britain] called 999, which were true stories that were highly dramatized with blood and point of view cameras. So, they would sort of tell a news story, but they would really try and make it visceral. We didn’t do all of that, though, because there were too many layers.

Having a woman doing the ghost hunting was sort of unusual and quite fresh, but a bit of that was starting to happen. There was this show called Challenge Anneka, which was a weird piece of TV. [TV presenter Anneka Rice] would be challenged to, I don’t know, build a library in a day or something. She’d get her team and run around; there’d be polystyrene cups and talking to the camera. That was definitely a huge influence on us.

We had a five-camera [set up], which we perverted because normally you would shoot [TV] in packages, meaning you’d cut from camera to camera. I learned this backwards because I was from the film department. The [TV studio] guys had to teach me quickly, because we brought together two departments that really didn’t talk to each other—the BBC film and studio departments. They taught me how the cameras couldn’t cross with pennies and bits of string, because the wires would cut, diminish or interfere with the signal. We took the feeds of all those cameras back into the cutting room, whereas normally they’d be cut into packages by the vision mixer.

For the house itself, which was shot before [the studio segments], we had fixed cameras, which were themselves quite modern. They’re called cigarette cameras, because they were cigar-sized and fixed in the corner of rooms. Then, of course, we had the roving camera with the cameraman, who was a genuine cameraman with a genuine sound guy. If I had actors using the camera, the footage would be poor and not as well-crafted as it would be for TV. I didn’t want to have an actor pretending to take footage, which would mean we’d have to shoot the footage again. So, we just put word out to the BBC and said, “Does anybody want to be on camera and play themselves?” One cameraman and one soundman came back, so they got the job.

Then it got more complex, in the sense that the actress playing the mother, Brid Brennan, would come out of the house and go into the back of a little van to talk to the camera [and communicate with the hosts in the studio]. But because I wanted a freshness and a reality between the mother talking to the parapsychologists or Parky, I brought her into the studio three weeks later. So she’d come out of the house and go into the van, and that was the end of that footage. Three weeks later, I put her in a little curtained section on the corner of the studio so that they could genuinely respond to each other, so that they weren’t always acting to pre-taped dialogue. On the other hand, Parkinson had to react to pre-taped dialogue [for the footage projected on the studio wall], which he was very good at because he had come from live TV. We would choreograph these huge takes, then rehearse them, and he would really get it down.

Filmmaker: That definitely sounds like a lot of moving parts.

Manning: It was massive, actually. I mean, the [visual] language wasn’t as complex, but the choreography was. Also bringing it into the cutting room, I suppose.

Filmmaker: There’s even a faux-lagginess between the news correspondent on the ground and the people in the studio. It has an authenticity to it, and it is really quite perplexing how you were able to time out all of that to include those human imperfections in communication.

Manning: Yeah, I was slightly obsessed with mistakes, because those are the bits I really liked. That was just from my own childhood, when you were watching the news and someone would scurry [in the background]. You’d think, “Oh my God, what’s happening in the newsroom?” Those mistakes also add another layer of anxiety.

Filmmaker: I’d also love to talk about how you directed the blend of actors, non-actors and news personalities incorporated within the film. There are obviously the BBC news hosts, who are comfortable in front of a camera and even improvised some of their lines. Then there are actors, such as Dr. Pascoe, the Early family and neighbors who offer revelations about supernatural occurrences in the area. Finally, if I’m not mistaken, some of the vox pop woven into the broadcast were sourced from civilians recounting their real-life ghost encounters. How did you balance these myriad interactions and dialogues that spanned such varied backgrounds?

Manning: Yeah, the vox pop were genuine people. It was quite humbling, actually. We had access to people who had [supernatural] experiences, and we asked them to come in and tell us their stories. Sometimes they found it quite difficult, but once they realized I was genuinely interested, they would open up and tell these amazing stories. I was quite shocked how they didn’t want to tell you anything until they trusted you, which only made [the film] more effective.

The Gillian/Dr. Pascoe and experienced TV interviewer [dynamic] was a whole other ball game. When we got into rehearsal, Parkinson was totally game for all of this. But as you know—well, maybe you don’t—there are two very distinctive styles that he had. He would have autocue, reading the script as it goes up, which has its own rhythm; it’s semi-poetic. There’s something really obvious about it, and it’s usually quite informative as well. Then he also had this wonderful style that was unique to him, which was very relaxed, like when he would interview celebrities. That was the style that I wanted; I didn’t want autocue, except for when he introduces the show at the beginning. But when he was learning the script in rehearsal, he sounded like he was on autocue. So what I did was I asked him to focus on the points that he needed to make for Gillian, who was a trained actress and waiting for her cue lines—which never came [laughs]. We had this way of working where he knew he had to make this point, then another point and finish, then Gillian could pick it up. So, we were sort of pure to the script, but we had that comfortable realism that [Parkinson] has.

Filmmaker: There’s definitely a calmness to him, but he also conveys a cattiness in his responses that’s really quite delightful.

Manning: I know! He helps [the film] massively by undermining it.

Filmmaker: I’m curious about how you directed the young girls in the film, because their performances are just chilling, really. What direction were they given and what was the environment like for them on the shoot?

Manning: It was a very warm environment and a very safe set. Sarah Greene worked brilliantly with them and kept them very close to her. She was sort of their surrogate mother, both on set and in the fiction of the film.

Filmmaker: You can 100% see that in the film, yeah. She tucks them into bed, kisses them on the forehead. It’s really sweet. But I can also imagine that warmness being necessary because of the intensity of the material. They convey that intensity amazingly, though.

Manning: I mean, they loved every minute of it. They just loved being the center of attention and being on set. They were actually sisters, which I really liked because they had that comfortableness with each other that I think would’ve taken more time if they hadn’t been real-life sisters.

Filmmaker: You’ve previously stated that your intention was to have Pipes appear 13 times in the film. However, there’s still an ongoing debate among Ghostwatch fans as to how many times he actually shows up. I think I counted eight, but it’s hard to say definitively since he’s often shrouded in the blackened background of otherwise ordinary shots. Were these appearances written into the script, or did you negotiate where to place him during filming?

Manning: So, this is interesting. Yes, he was totally scripted. But if we paid [Pipes actor Keith Ferrari] for the day, then it wasn’t beyond me to sneak him in everywhere I could. So he just might appear in scenes that he wasn’t scripted in, only because he was booked for that day. Looking at a marked-up script, I can see I requested him for a day that wasn’t in the script, but I think nine is actually the official fan number.

Filmmaker: You’re going to drive me crazy looking for an additional Pipes I can’t see!

Manning: As far as an official number goes, though, I’m going to leave it a mystery.

Filmmaker: You should. It’s interesting, because horror as a genre has long centered women’s stories. Despite all of these demographic quotas in the film industry that people are continuing to fix, horror is a genre where you’re very likely to encounter a female protagonist. There’s a fascination with the female form, with womanhood, with puberty. Yet Ghostwatch, as a woman-directed horror film, doesn’t even entertain the idea that everything is happening because it’s a single mother-run household. It doesn’t insinuate that without a strong male presence, you’re going to open yourself up to evil, which I think is a common critique of The Exorcist. And to have Sarah as the on-the-ground newscaster, again, reverses that gendered expectation of a man coming in and fixing this problem. I think Ghostwatch subverted a lot of expectations about a woman’s place in the horror genre.

Manning: It’s also interesting to have Gillian as the parapsychologist. The norm for an expert source would have been a male, right?

Filmmaker: Yeah, and the counter-voice to Dr. Pascoe is the scientist from New York, who totally speaks down to her. Parkinson even teases her and says something like, “Oh he got under your skin, didn’t he?” As a woman watching that exchange, you’re infuriated that the scientist is able to make all of these rude comments without any repercussion; he makes their ideological difference so personal for no reason. Again, having these women in roles of authority wouldn’t have been reserved for them in the past, especially for what’s ostensibly a news broadcast, which is the “official record.” That exchange adds some gendered insight into that struggle.

Manning: I mean, I thought we were way out there when we gave [Dr. Pascoe] a really lovely suit with a mini skirt. If you were brave enough to have a female expert [on your show], they would’ve been dressed like a man. You know, buttoned-up with a dull on-the-knee skirt, a boring haircut. And we had this jazzy broach! We wanted her to be a real thinker, who could be attractive and modern. The norm in ‘92 was that if you were a female expert, you were dull.

Filmmaker: Or you at least had to present yourself as such, because being overly feminine would discredit you almost entirely.

Manning: Exactly, It’s mad, but true. There was a feeling that you couldn’t be intelligent and attractive.

Filmmaker: The Blu-ray release of Ghostwatch will finally make the film accessible to Americans as a piece of physical media. I’d really like to glean a bit into your involvement in this 30th anniversary release, and what you’re particularly excited to share through this new document?

Manning: I’m just really thrilled that it’s 30 years on and it still seems to gather interest. I’m surprised and pleased. This year was really good for us [in England]. We had two or three really interesting screenings with Augmented Reality, trying to make it quite scary. We introduced the film, it was shown to full houses, then we had a Q&A that “went wrong” and was supposed to scare the audience. We did that in Sheffield and London, so we had a little bit of a tour. I suppose people feel that [Ghostwatch] has influenced a few things, and I think that’s part of the interest as well. It’s great as a female director, too, because it’s very easy to be invisible. There are plenty of things that I still want to make.

Filmmaker: Speaking of that, I’m curious about what’s next for you. Are you still working with Stephen Volk on Extrasensory Perception?

Manning: Yes, definitely. We are really excited about it. I don’t want to say too much, but yes, that’s true. There are other projects as well, which I really hope come together.

Filmmaker: This Ghostwatch reevaluation is great for many of us because it’s a wonderful discovery, but it also offers so much insight into how difficult it is as a woman director to navigate this landscape, particularly when a film does garner controversy. It can really halt or stagnate one’s career, even though it’s reportedly an influence on other horror phenomenons like The Blair Witch Project. I mean, it also took forever for audiences to revisit it because of the ban and issues with distribution. But this should be a lesson in fighting for women directors who deserve to flourish creatively.

Manning: I completely agree. I think it’s changing now, there’s definitely a tide turning. I just feel that the unconscious [gender] bias has been quite well entrenched. It’s no wonder, really: if you’re a second-class citizen for hundreds and hundreds of years, it’s very difficult to unpack that mindset. I think that people and the industry are really trying, though. Interestingly, I’m working on a play where we’ve decided to make the protagonist a woman instead of a man, just as an exercise, really, to make it a bit fresher. But it shocked me completely how it unpacked a lot of preconceived notions about women and their position in society. The play is basically about a woman alcoholic. You know, guys are allowed to go down to the pub and get drunk, but it really unnerves society when women are out of control and can’t look after their family. It really opened my eyes about my own preconceptions, as well.

Filmmaker: Sometimes it’s hard to confront that. Like, “What the hell? When did I get indoctrinated into this thinking?”

Manning: Absolutely. Sometimes I have to stop myself and go, “OK, let’s put a man here. What do I think about that? Now let’s put a woman in that role.” You find these shifts in your thoughts. And we at least are aware of these thoughts! So many people aren’t. It’s scary.