Back to selection

Back to selection

The 1998 Cannes Film Festival

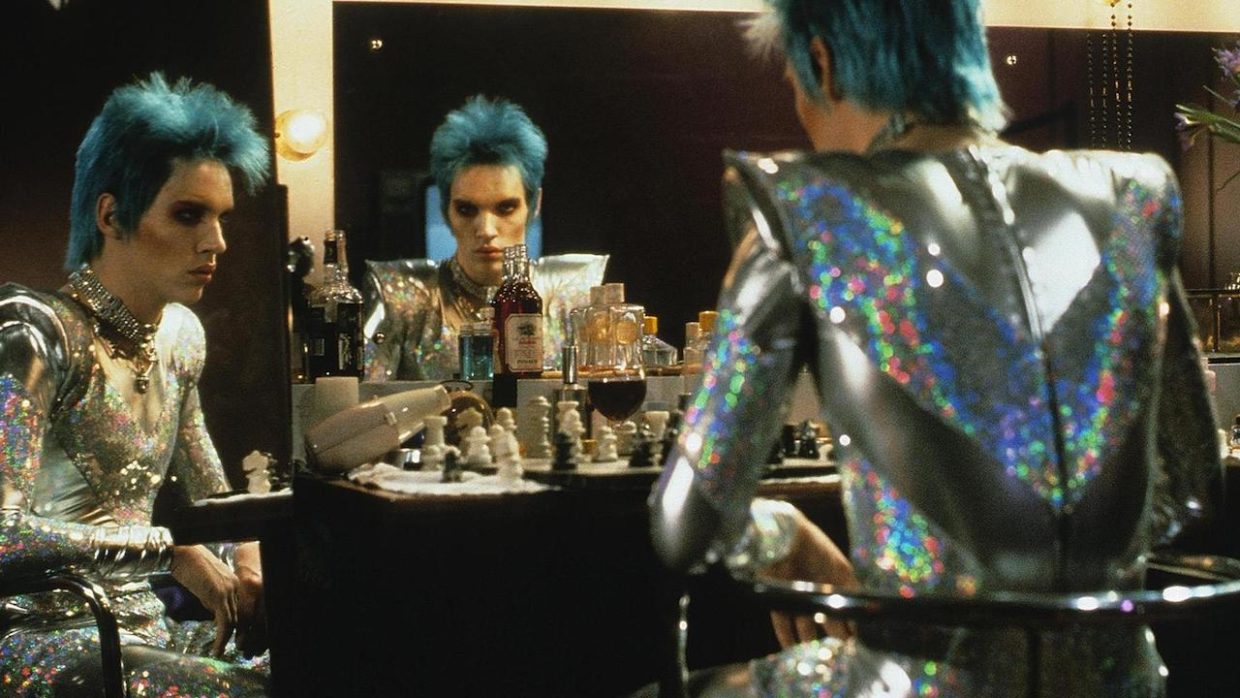

Velvet Goldmine

Velvet Goldmine While many important films premiered in front of attractively dressed people at this year’s Cannes Film Festival, the big story on the beach was the regal blessing accorded the American indie scene. Four films appeared in Competition plus a handful in the Director’s Fortnight, all produced in the United States outside of studio-based development and production systems. Further risking immodesty – after all, Filmmaker is a cheerleader for just this kind of work – the Festival was even more specifically laudatory: it celebrated the filmmakers who emerged from New York in the early ’90s and their powerful aesthetic influence on the film world

I primarily mean two people here, Hal Hartley and Todd Haynes, who appeared in Competition with Henry Fool and Velvet Goldmine respectively. But I also mean Clean, Shaven’s Lodge Kerrigan and the actor-turned-director John Turturro, in Competition with their new films, Clare Dolan and Illuminata; as well as Welcome To The Dollhouse’s Todd Solondz, with his newest Happiness; novelist Paul Auster’s first film as sole director, Lulu On The Bridge; Tamara Jenkins’s Slums Of Beverly Hills and Sundance winners Mark Levin (Slam) and Lisa Cholodenko (High Art). This is a particularly fine cross-section of filmmaking talent from New York and represents in many ways the breadth of accomplishment that has happened in that city over the last decade. For the Queen of Festivals to take on a bargeload of films from the same gene pool is, especially in France, very much a political act – especially for those of us who remember waiting for the annual lone American independent selection to be announced. Obviously there are huge disparities in accomplishment between these films. Nevertheless, the best of them represent the most thoughtful and radical positions available in narrative filmmaking today. Festival director Gilles Jacob and Fortnight director Pierre-Henri Deleau seem eminently justified in choosing this year for their coronation ceremony a l’Americain. And this consensus is more surprising than it might at first look.

“Cannes” is actually three or four different festivals, administratively separate and jealous of each other’s position, which take place in the same legendary town. While one would be hard pressed to call the place “magical” or “breathtaking” (per the Huck Finns of American journalism), it does have a certain faded allure in its glamorous (if aging) beach side palace hotels – the Carlton, the Martinez, the Majestic – and the Monegasque yachts moored off the azure Cap d’Antibes. The stone monstrosity that houses the Festival itself, the Palais des Festivals, looks more like a Vegas convention centre a la ’70s Elvis than the film mecca it represents. Even so, its facilities are irreproachable: films just look better on those big screens. Of course only the films of the Competition and Un Certain Regard (the farm team) play there. The Director’s Fortnight is in a fairly grim basement, albeit with terrific projection, in the Noga Hilton hotel; the Critic’s Week plays out in two unspeakable town cinemas and the films of the Market play in cinemas used so occasionally that fantasies of Legionnaire’s Disease regularly play across one’s mind.

The Competition was, according to the New York Times and a few others, relatively disappointing this year. This is fair; few films made for a good brawl and that’s the great joy of festivals. The only official outrage really came from the Danes, with their two films in Competition produced under the “Dogma 95,” a manifesto (more or less) demanding the application of the principles of Lars von Trier’s Breaking The Waves to the films by the undersigned. That means lots of hand-held camera, naturalistic performance, on-sight sound, few opticals, little cross-cutting and, I suppose, a desire to expose the hypocrisy of Danish (or European?) society. The film that people liked, Celebration by Thomas Vinterberg, sees a large rich family gathered at a country hotel to celebrate the patriarch’s birthday. Hatreds are on the surface and none of the relatives – even the hero, a self-contained blond cutie-pie – are particularly nice. Things are kept in check until the cutie includes in his toast a reference to his and his sister’s molestation at their father’s hands. This dramatic moment is then impressively sustained for another 20 minutes of knife-twisting pain until the proceedings recede to the ordinary staples of the “evil parent” movie. The film’s relatively conventional narrative arcs and movie-of-the-week themes provided enough comfort for most critics so that the film’s often impressive cruelty and austerity became more digestible.

Not so with Lars von Trier’s newest, Idiots, loathed by critics and public alike. This is an art film as confrontational and mean-spirited as anything Fassbinder ever made, in an era not accustomed to such aggression. A dazed-looking middle-aged woman gets caught up with a bunch of rich kids living communally in a beautiful suburban house owned by the group leader’s uncle. For no reason they feel the need to explain, their sole passion in life is to go into public settings – a community swimming pool, a roadside restaurant, a factory “open house” – and “act like spazzes”. They imitate people suffering from mental illness in order to wreak havoc, eliciting only pity and stern looks. While the inevitable happens – the leader tries unsuccessfully to get everybody to integrate “spazzing” into their work life; the house gets taken away from them; the group breaks up – the build-up to its denouement is a fascinating exercise in audience humiliation. Do you laugh? The situational humour is flabergastingly funny, especially within the documentary realism of the “Dogma,” but virtually every scene contains a moment of very “bad taste.” Just when you think you have it solved – Ahh! They are showing their contempt for society by showing how easily disrupted it can be! – von Trier raises the ante of offensiveness one more notch, challenging you to call him a dumb Neanderthal. I found it brilliant. The film also has one of the great final payoff scenes ever filmed; and even this does not resolve the central enigma of the work.

The only other film that prompted this much reflection in Competition was Haynes’ Velvet Goldmine, even if it is Idiots’s emotional opposite. A heartfelt gay love poem to rock’n’roll, Haynes portrays glam rock through a series of characters whose worlds are (almost) purely historical. Told mostly through voice-over flashback, press “happenings,” public (or publicly-staged) events and tons of performance, the film provides maybe three conventional narrative scenes – you know, where people reveal things about themselves through dialogue – to hang the story from. Because of this, Haynes was accused of making a “cold” film; nothing could be farther from the truth. The giddy expectations of fame, the transience of love, the ego-driven glory of being loved; it’s all there. And told with a stunning camera and jaw-droppingly sexy songs.

The balance was made up of the charming (Erik Zonca’s enticing Paris saga The Dream Life Of Angels; Nanni Moretti’s conflation of his son’s birth and the rise of the Italian Left, Aprile); the sternly formal (Theo Angelopoulos’ Eternity And A Day; Hou Hsiao-Hsien’s Flowers of Shanghai) and the failed crowd-pleasers (Turturro’s Pirandello-esque Illuminata and, although the rest of the planet seems to be charmed, Roberto Benigni’s ridiculous Nazi comedy Life Is Beautiful). Hartley’s film has been addressed in this magazine already, but it is worth saying again that it represents a major advance for his “Dogma” and a welcome broadening of his artistic scope. Out-Of-Competition is reserved for Hollywood garbage and films by very old men. In the latter category was Carlos Saura’s newest dance opus Tango, Manoel de Oliveira’s newest meditation on whatever all the others are meditations on, Inquietude, and a small delight from Shohei Imamura. His Kanzo Sensei tells the story of a country doctor celebrated for identifying chronic hepatitis in wartime Japanese civilians; but he humorously subverts the cliches of the historical biopic by adding incongruous sex talk, morphine junkies and the other exquisite twists we have come to expect from this ever-surprising septugenarian.

“Un Certain Regard,” the parallel section programmed (basically) by the Competition folks, always suffers by comparison with the Competition on one hand; and with the Director’s Fortnight, with which it shares the same “vision” – new or challenging work, (somehow) inappropriate for the Big Room – on the other. Last year, a particularly strong collection of films in this section (of about 30 features) was thought to signal a new seriousness in the section’s programming; less a football for political selections and more a truly “informational” section about the goings-on in world cinema. A few baffling choices – all American, interestingly enough – put this new thinking into question, but the general tone was still very positive and several important new films premiered here.

Clearing the American turkeys out of the way first: the opening film of the program, Paul Auster’s Lulu On The Bridge, was a disaster – an overly-determined love story, premised on a flaky New Age concept, with a retro-silly jazz vibe and somnolent acting — it was a monumental disappointment in the wake of the light-hearted and charming Blue In The Face, for which Auster received a co-directing credit. Jake Kasdan’s Zero Effect, an unnotable winter release in America, was given star status in the program, rather clouding Kasdan fils’ denials of nepotism. Stanley Tucci’s new film The Imposters adores the uproar and showmanship of the Silent Era and designs a story of two actors who become stowaways around the period’s most famous stylistic moments; yet its effect was less than inspirational. A complicated failure – is period slapstick too erudite? How do you make accessible films about performers (after Ishtar)? And those costumes, post-Sting? Finally, I suppose, Tucci chose not to believe that much of silent cinema’s charm came from people not talking.

As for the triumphs, consider these radically different three. Divineis a zeugma of the Old Testament and Seven Stations of the Cross according to Mexican cinema god Arturo Ripstein (Deep Crimson). Enigmatically mixing chapters, restaging it all in a low-rent Christian cult in the scrub and featuring a nymphomaniac Virgin Mary/Moses obsessed with a sub-Mario video game, the film is arrestingly intelligent and deliciously fun. The Killer is the latest in Darejan Omirbaev’s films (also Kairat and Cardiogram) about the Kazakhs in post-Soviet Russia; for my money, his descriptions of the inevitability of a life of crime and the nihilistic collapse of any societal values in post-Soviet Russia outgun the much-celebrated, similarly-themed and recently released The Friend Of The Deceased. John Maybury’s film about Francis Bacon, Love Is The Devil, was described recently by a (decidedly unhomophobic) friend as “too ‘gay,’ overdetermined, reductive and overly stylized.” These criticisms have a certain justice: the film is unflinching in matching Bacon’s unconventional use of light and figure with the film’s cinematic look; the connection between the sense of inevitable decomposition in Bacon’s paintings and the eerie way the painter’s relationship collapses with his East End stud boyfriend also signals both a singularly gay nihilistic approach to human relationships and draws on an obvious “tortured artist” genre. Were this simply just another po-mo graveyard run at a gay anti-hero, little more would need to be said. And it is true that Love Is The Devil may have at its center a tragic, mean-spirited fag and a loutish exploitative drama queen of a boyfriend. For many of us, that makes the film’s ability to convey a core of (tortured, spiteful, repellent, utterly moving) romantic love so extraordinary. Maybury’s genius is to rest a fragile melodrama on an ultimately awesome if dense edifice of theory, history and cinematic representation of artistic accomplishment. I also defy any critic to show me a narrative film with this many images that appear entirely new.

Reeling from a tragic 1997, the Director’s Fortnight returned with a triumphant 1998. A consistently strong, focused and intelligent selection challenged the Competition daily with its “finds.” The consensus triumph of the section was Todd Solondz’s formidably intelligent and extremely funny Happiness. While every hack this side of the Pacific will write about the film’s “troubling pedophilia,” the real story is his audacious appropriation of Robert Altman’s narrative style and ability to make it relevant again. After Nashville, Altman used the shaggy-dog style to avoid the full exploration of the often troubling questions he posed on the surface of American society. Solondz looks like he is doing the same until we are suddenly upbraided by the consequences of the action of his characters and our laughter. So, while the Jersey father’s admission to his son that he’s drugged and screwed the kid’s best friend is quite a scene, a flaky girl’s realization that her dreamy affair with a Russian taxi driver caused his wife to be beaten to a pulp somehow becomes far more horrifying because it is so genre unfriendly. This brave film is a monument to the brutal efficiency of sardonic wit.

Also in the Fortnight was Yvan Le Moine’s charming, very sexy Fellini tribute, Le Nain Rouge, about a dwarf who writes love poetry to a rich zaftig starlet (played, of course, by Anita Ekberg); Don McKellar’s perfectly scripted, stunningly shot (in radical brown and gray contrasting shadows) and poignant meditation on the world’s end, Last Night, was a triumph for Canadian cinema; Ziad Doueiri’s West Beirut intricately immerses two teenage boys just looking to get laid on the newly-drawn Green Line in early civil war Beirut; Mimmo Carlopresti’s La Parola Amore Esiste encapsulates a very contemporary fear of some Europeans that the capacity for love may have been eclipsed by a need for spurious personal insight, driven by both therapy and our individualistic society. Also notable was the great success accorded Sundance triumphs High Art and Slam in this section; the French went crazy!

The Critic’s Week felt smaller this year; smaller even than its official role as the smallest official Cannes section. This was mostly because it was tossed out of the Palais des Festivals, and forced into commercial cinemas too small to accommodate it. A couple of the films it presented were very good. Gaspar Noé’s Tous Contre Moi is a frighteningly powerful bile-spewing from inside the mind of a (in Noé’s mind) “typical” Frenchman: racist, sexually obsessive (especially about his daughter), murderous, mean-spirited, cheap, etc. An obviously caustic portrait of current France, it is always cinematically intense and enriching in a sort of filthy way. Francois Ozon’s Sitcom is the lighter side of Noé’s vision. All the evil and sexual perversity of Tous contre Moi is here but wrapped in, well, a sitcom. A mouse enters a well-adjusted household and transforms everyone into their true inner self. The nerdy son turns into a promiscuous fashion queen, the daughter becomes a sadistic suicidal horror, the mother a Mother Teresa sexually obsessed with her gay son and the father seemingly stays the same. A total hoot until it loses itself in the last ten minutes, Sitcom will surely enjoy a happy run at gay festivals and perhaps in a few theaters.

The Market usually yields some gems. Not this year. The great hot “find” was meant to be Waking Ned, an irritatingly twee tale of two Irish country geezers who stumble onto the winning ticket of the big lotto in a dead man’s hand. Perhaps retitled The Full Blarney,because it is surely born from the same school as that middlebrow rubbish, it will find its pot o’ gold underneath the Angelika rainbow promised by its selling price – a figure far in excess of any film I described above.