Back to selection

Back to selection

“I Become a Better Designer Every Time I Work with David”: Production Designer Jade Healy and David Lowery

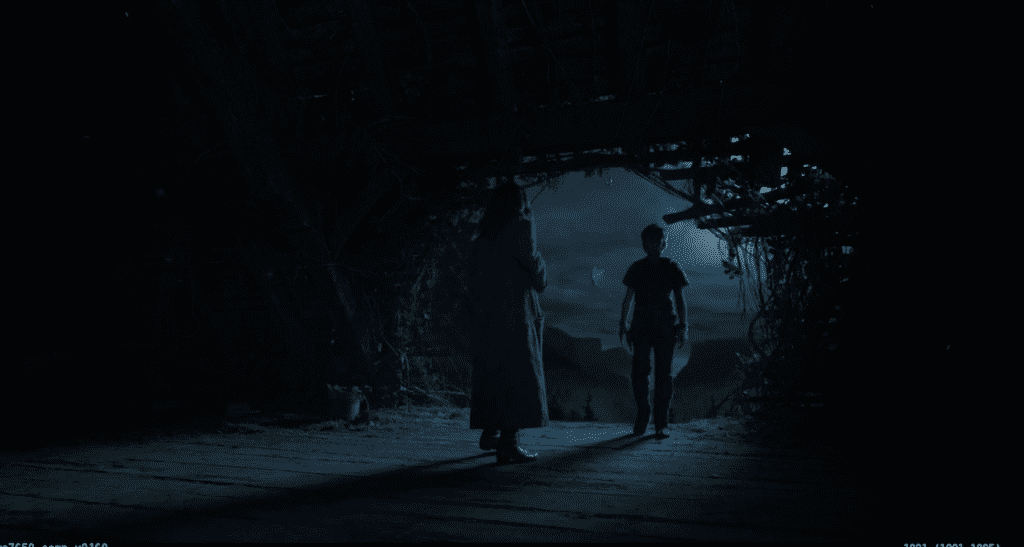

David Lowery and Jade Healy on the set of The Green Knight

David Lowery and Jade Healy on the set of The Green Knight Ahead of the first-ever International Production Design Week, the Production Designers Collective has coordinated a series of interviews with directors and production designers, in which they discuss their working dynamics and mutual passion for the craft of storytelling. Below, is the first of these conversations published at Filmmaker, a conversation between production designer Jade Healy and director David Lowery.

Their first collaboration had them wearing different hats. Shot in Costa Rica, It Was Great, But I Was Ready to Come Home was written by four friends, among them Jade Healy, an actress, and David Lowery, sound designer and editor. Years later, as David was preparing for his second feature as a director, Ain’t Them Bodies Saints, he realized that Jade’s evolving production design work fit his vision and reached out to collaborate.

Filmmaker: Tell us about your starting point for collaboration.

Lowery: On Ain’t Them Bodies Saints, I had random pieces of imagery as references. I always have a collection of images at the beginning of a project, plus the script, which is usually very visual. I tend to write scripts that feel more novelistic, where the prose communicates a texture and tone. It sets the template for the exchange of ideas and aesthetics that Jade and I then embark on together.

Healy: With David’s scripts in particular, when I read them I see the film in my head. We have a similar visual language, often steeped in nostalgia and timelessness. It’s about the translation of a feeling or emotion. I spend time meditating on what that feeling is, then try to extract those images from my head to show David. I also think David and I spent a lot of time talking about the script, and those conversations drive the film and the world that we’re creating.

Lowery: So many of my movies are reactions to things happening in my own life. Talking through those things, and hearing Jade’s personal connection to the same issues, is just as important as looking at references or wallpaper samples. Knowing the ways in which we internalize these stories and make them our own gives me the confidence that every design choice is coming from a very personal and passionate place. It’s a really beautiful safety net, to know that I have collaborators who are as invested in the story as I was when I was writing it.

Filmmaker: Is there one element of the design process that you connect through the most?

Healy: I create extensive lookbooks that I share with David, then we scout together and think about spaces. On our first films we were working with locations, but now we’re doing bigger films and have to invent whole worlds from scratch, so we’ve incorporated concept art. The process is constantly moving and is never set in stone.

Lowery: Prep is where you’re figuring it all out, but it never actually stops. Especially lately, as we’ve made movies that incorporate more visual effects, the production design doesn’t end with principal photography. That collaboration has extended beyond the old constraints of a production machine, where you put all of the effort into prep, shoot the movie and part ways. Now we keep designing and developing things after we finish shooting.

Healy: I always think about how on the first movie David and I did together, the entire budget was three million dollars. It felt like we had money. On our last movie together, my art department budget was larger than that. But the process is always the same.

Filmmaker: On that note, you’ve worked on both indie and large budget films, but always manage to deliver a perfect vision. What were some challenges you’ve had to face in your years of collaboration?

Lowery: Each project is hard in its own way, but the hardest from my point of view was The Green Knight, because we were trying to do something quite epic and we didn’t have enough money for it.

Healy: We managed to make something really special with the amount of money we had. That is the trick when you’re designing—you have to think in the box and outside the box at the same time. The Crooked Tower in The Green Knight is an example of how our vision was shaped by limitations. That set should have been a stage build, but we didn’t have the money, nor the stage space. So we found this empty boring barn on the lot, that had one wall of actual ancient stone and a pretty cool ceiling, and we transformed it. Sometimes when you have these parameters, exciting things happen.

Lowery: That barn ended up being so inspirational.

Healy: In some ways when you’re doing a tiny movie you’re more free. On our first big movie, Pete’s Dragon, the funny thing was that we had so much money, but at the same time a lot of limitations. Suddenly your crew is so big that mobilizing and moving people becomes a task. There’s something amazing about doing giant movies, but I also cherish films like A Ghost Story, which are so small and intimate.

Filmmaker: You’ve both worked with other filmmakers aside from your collaborations. What defines your work relationship?

Lowery: When I’m working with Jade I get to fall back on the comfort of us understanding each others’ tastes and sharing them on such a deep level, that there’s less explaining, and more inventing. We invent together. The few times we haven’t worked together, I’ve had to really think about what it is that I want. I have to define my taste in much more concrete, tactile and practical terms. It’s actually incredible to have that opportunity to define for myself what I want, and to put my vision into words.

Healy: David and I haven’t always agreed on every single thing. Sometimes he’ll make a script change, and I’ll send him one of my giant emails, which I’ll spend an hour writing, about why that script change shouldn’t happen. We have that relationship because we’ve been working together for so long, but also because I’m not afraid to go there, and I know he’ll appreciate that.

Lowery: On film sets you often hear people say “stay in your lane,” but I love it when people don’t stay in their lane. Film is such a collaborative art form, so I want those huge emails about why a script change may not be the best idea. On my sets, if my crew thinks I’m missing something, I’d rather be told. It is really meaningful to me as a filmmaker to know that people are paying attention and care that much. It means I’m surrounded by people who are invested in this project on more than just a technical level.

Healy: David doesn’t know this because he doesn’t work on other sets, but that’s very rare. He creates such an open and inviting environment, where collaboration is key, so people feel safe expressing themselves. That is such a magical thing, which is a constant in working with David. Everybody feels that they can add something. I learned a lot about collaborating with my own art department from seeing the way David works. I want everybody, from my interns to my set designers, to feel like they’re part of the creative vision.

Filmmaker: It’s interesting to hear you speak about your process, which seems both specific and fluid at the same time.

Lowery: There’s a specificity that comes into play, but there’s always this energy, or spirit, that we’re trying to reach for. What I’m after is a specific vision towards something that is shimmering in the distance, that we can’t quite wrap our fingers around. Having that vague north star leaves so much room for discovery. We will never quite get there, but we’ll get somewhere beautiful that we weren’t anticipating.

Healy: You’re building the monster and then you follow it to see where it goes. I love that kind of collaboration, because it allows for growth and evolution.

Filmmaker: When you sit down to watch a film in a movie theater, what is it that defines for you compelling or convincing production design?

Lowery: I’m always looking for a cohesive vision. I like the movies to feel of one piece, regardless of how many people contributed to them. I like that sense that everyone was working on the same tapestry together.

Healy: The feeling of being transported. Being immersed in that world and forgetting the artifice of filmmaking.

Lowery: I respond so much to tangibility and texture in films. Whenever I feel the artisanal touch in a film, I sit up a bit more in my chair. That sense of craft, love and attention to detail is something that I seek in my own work. What we’ve always tried to do in our movies is shoot on practical locations, or build full sets, and limit the number of days we spend on green screens. One of the great joys of Peter Pan and Wendy was getting to build all of those gigantic sets.

Healy: What I appreciate about working with David is that we always try to create 360-degree sets, even though these days the tendency is to extend sets digitally through VFX. In The Green Knight, there was no extending. In the Great Hall, we built a vaulted ceiling. It was a massive undertaking, but it was amazing to step into. I really believe in creating a world for the characters and for the actors who portray them.

Lowery: When a production designer can give all of us on set an environment we don’t have to imagine and are able to react to, it’s a great gift.

To check out the complete program of International Production Design Week, go to productiondesignweek.org