Back to selection

Back to selection

Emergence

New work in new media by Deniz Tortum

In an Instance

Tulpamancer

Tulpamancer During the pandemic, while I was stuck at home in Maryland, a friend from California suggested that we catch up in virtual reality. This had been their favorite pandemic activity. We set a time and decided to meet at a specific room in VRChat. When the time came, we were both in our headsets, logged into the same space. The virtual room was crowded, and we couldn’t find each other. I called my friend, and we tried to coordinate our locations over the phone. We went to the same corner of the same room but still couldn’t see each other. It turned out that we were stuck in different instances of the game server. In many multiplayer experiences, worlds are separated into instances: Each server hosts a limited number of users, and when there are too many, a new server instance is spun up. There were probably thousands of people in the same room, but each instance was only able to host around 40 to 80 people. We tried several more times to restart and get on the same instance, but ultimately we couldn’t meet. After an hour of trying, we decided to just talk on the phone.

I’ve since been thinking about this event, about being stuck in our own worlds and not being able to meet. Can an “instance” be an appropriate metaphor for aspects of our current technological existence, almost a more physical or embodied manifestation of our social media timelines, of our “filter bubbles”?

Our mental worlds have different physical manifestations. In the past, it may have been a room decorated with posters, a bookshelf, etc. Now, this externalization mostly happens through technological means—Twitter timelines, Instagram feeds and other algorithmic structures—and we no longer have the means to share our mental worlds. We could invite people to our rooms, but today we can’t share timelines with each other. We live in different instances, and we don’t always have the means to meet in the same one.

In September, I was presenting Shadowtime, a VR work I co-created with Sister Sylvester, at the Venice Film Festival’s Venice Immersive. Now in its seventh year, the XR-focused Venice Immersive takes place on the Lazzaretto Vecchio island, which, historically, was a quarantine island and then a military armory. Now, it’s a place bringing viewers from all over into virtual worlds.

When you walk through the corridors of the island, the environment becomes a zone of “instances”: Although everyone is sharing the same physical location, they are all in different virtual worlds. These virtual worlds are created via the affordances of the VR headset: two encompassing lenses that provide stereoscopic vision, the body-tracking sensors and the real-time imagery that presents an image in sync with the user’s body movement. The VR headset is a device designed to fully immerse us in another world. That means it is also a device to separate ourselves from the physical world by intercepting our perceptual systems at their interface. What if the VR headset could be considered a device that physically manifests instances in real life? This tension became a creative tool in several works at the Venice Immersive, particularly in Songs for a Passerby and Tulpamancer.

The winner of the grand prize, Songs for a Passerby is a VR opera created by Celine Daemen. Employing techniques learned from a decade of collective VR experimentation, Songs might be one of the first mature and complete VR art works I’ve experienced. You start the experience by following a dog through the darkened corridors of a decaying cityscape. You walk laps around the rectangular real-world physical space. Every time you complete a lap, you arrive at a different scene in the virtual world—an injured horse on the street, a subway car full of murmuring people, the top of a building where you see all the previous scenes. An impossible architecture keeps building on top of itself. A libretto accompanies your walk through the city. You feel like a ghost walking through this space (an audience member even described the piece as the fully-realized version of Wim Wenders’s Wings of Desire). At around the midpoint of the piece, through the Kinect cameras placed at the exhibition, you see yourself (your real-time volumetric image wearing a headset) within the virtual world and start following this doppelganger. This twinning leads to a finale in which you see all your previous selves, each at the different places you have passed through, at the same time. You exist right now, right here, as well as right now, right there, in the physical world, in the virtual world, in the present and in the past. Your existence in time, and in between virtual and physical worlds, is divided into many instances and presented back to you.

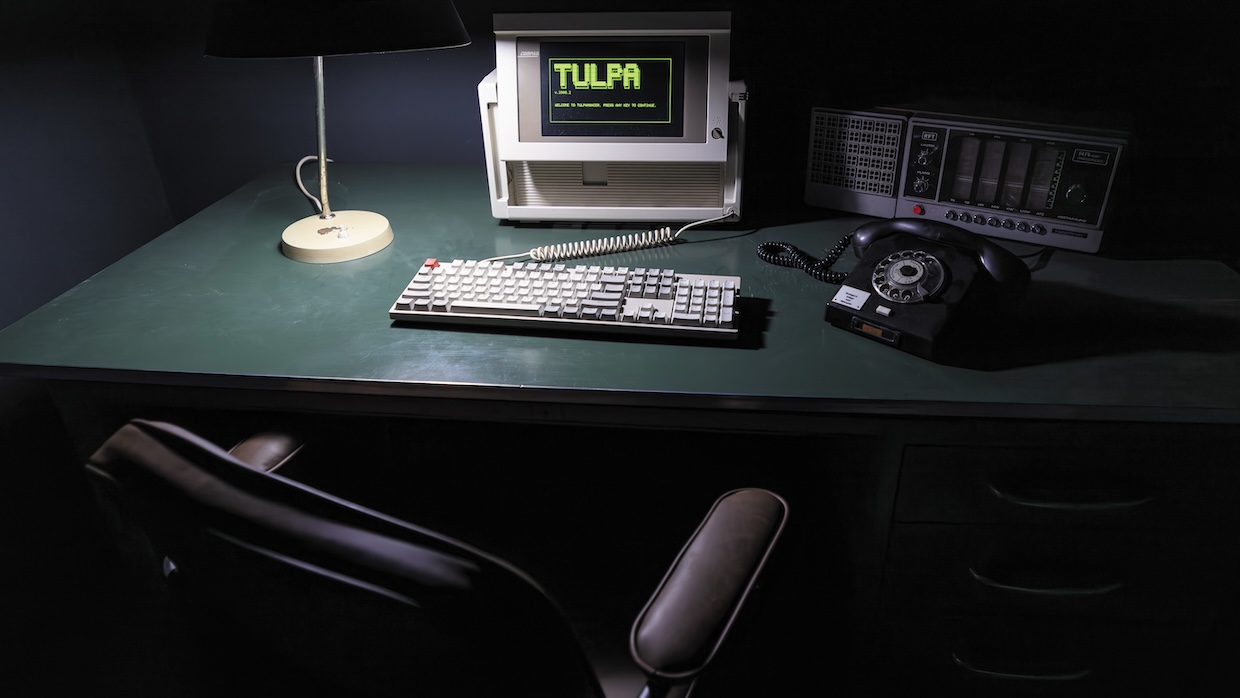

Tulpamancer, by Marc Da Costa and Matthew Niederhauser, creates AI-generated, personalized experiences. You first enter a 1980s-style room, which is part of the physical installation. There’s an old computer on a desk. The parafiction is that this computer has been found and retrieved and that it has a very complex AI system within it. The computer starts asking you questions, such as “What was your childhood room like? Tell me about a stranger you met today? Tell me something that makes you very happy?”

Then, you’re invited to a second room, where you wear a headset. The system takes the prompts you just wrote and turns it into a custom VR experience. An AI voice repeats your answers back to you in a detailed, ornamental fashion while you find yourself in AI-created spaces reflecting what you shared with the computer in the previous room.

On one level, this piece is a meditative tool for an individual experience. But also, the piece can be considered as a relational artwork. There is another dimension of experience that occurs only after the piece ends. Because each viewer has a different experience, it becomes hard to talk about this piece meaningfully without going into personal details. “Who was the stranger for you?” I ask a friend, and they are unwilling to share. Another friend says, “The AI system revealed a very interesting truth about myself, but I can’t tell you.” Someone else is very angry at the piece for flattening their experience and what they perceive as a self-imposing tone. When it’s designed as a personalization device, AI separates our own subjectivity further from other subjectivities.

Can we see Tulpamancer as a piece that creates easy-to-discern “instances” in the real world? Most of the time, it’s difficult to recognize our own filter bubbles. However, the discussions between viewers that emerge after experiencing Tulpamancer are explicitly about experiencing different instances. We can’t talk about the specifics of our experience, so we start to talk about the structural elements of the piece: What AI system does it use? Why is the AI voice in a British accent? What details are visualized in the generated environments? This piece provides a way to talk more explicitly about the structure that creates these instances and what they have in common.

Instances in virtual worlds have a material origin and have emerged as one solution to a computing power constraint. Being in different server instances is referred to as the “concurrency problem” of the metaverse. Even though the goal of the metaverse is to be a virtual social world, it is technically challenging to bring together more than 100 people in the same room. The current imperfect workaround is creating simultaneous server instances, which can be unlimited.

The concurrency problem exists in the XR industry as well. Many producers and exhibitors are asking how they may be able to break the single-user VR experience and have collective immersive experiences. Over the few days I was on Immersive Island, the topic of collective immersive entertainment came up repeatedly. Attendees were especially curious about new high-profile dome venues opening up, from The Sphere to the upcoming domes of Cosm.

The concurrency problem already exists in our everyday life. Factors such as class, geography, language and race divide our daily experience, affecting where we can go, what we do and who we interact with. The digital domain not only pushes this further, it also metamorphosizes and obfuscates that it is happening at all, creating new “concurrency problems.” A simple and rather innocent example: Google Maps directs drivers through different routes as a way to ease traffic, and sometimes this causes a residential street to feel like a small highway. Social feeds, algorithmic and AI recommendations and computational bureaucracy present us with different realities. The non-indexed cozy web (more sinisterly referred to as the “dark web”), country-level IP blocking and money-infused search rankings reinforce already existing hierarchies. These factors can lead to sharp polarization everywhere in the world: It is as though we don’t live in the same world with many other people, even if we are side by side physically or capable of communicating in real time across vast distances. There exist many instances of our world, but we don’t have the means to realize that we are not in the same instance. When used in a self-reflexive way, VR, AI and other immersive experiences can be a tool to discuss critically our technological way of being and knowing. In many cases, this capacity is what often drives people to dismiss VR as a medium—it is isolating, subjective, intervenes clumsily with our senses—but it is also a medium that physically manifests the “instances,” the experience of living in divided and layered digital and physical realities.