Back to selection

Back to selection

Clothes Tell the Story: Costume Designer Stacey Battat on Priscilla

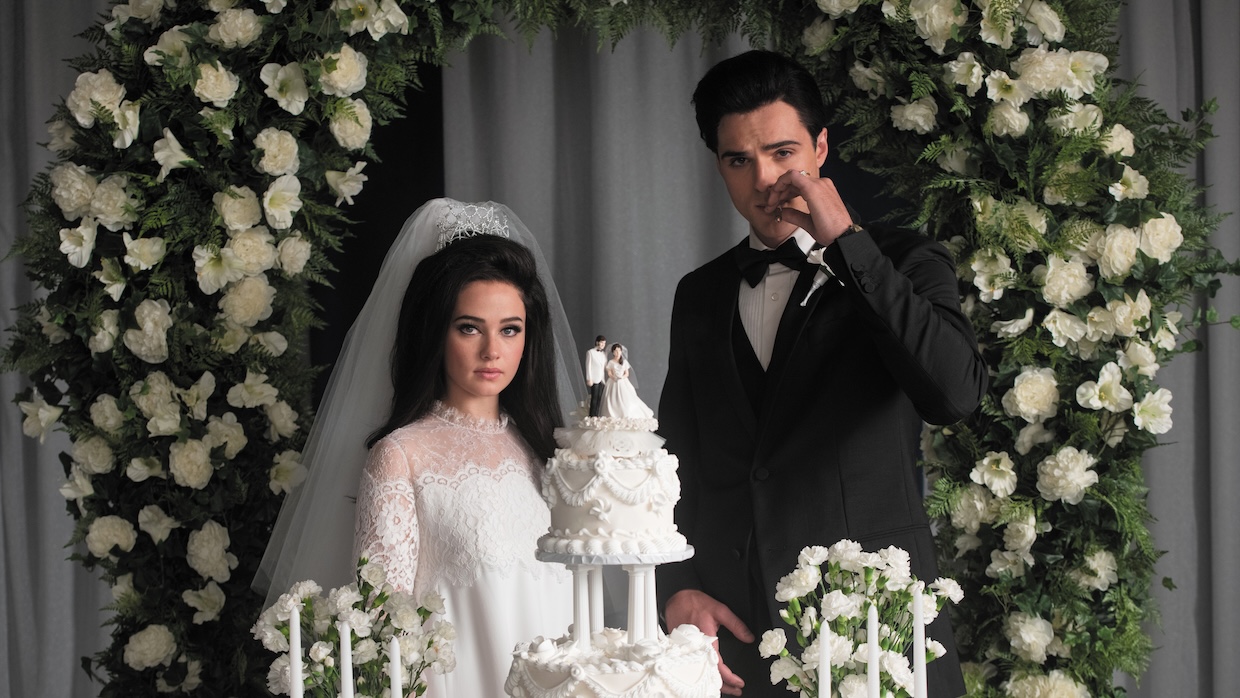

Cailee Spaeny and Jacob Elordi in Priscilla (courtesy of A24)

Cailee Spaeny and Jacob Elordi in Priscilla (courtesy of A24) From the wan pastel prairie dresses of The Virgin Suicides to the candy-colored 18th century finery of Marie Antoinette to the aughts logomania of The Bling Ring, the style in Sofia Coppola’s movies is always brilliantly cohesive, capturing a distinct, ultrafeminine vibe like no other. Coppola’s latest, the impressionist biopic Priscilla, follows Priscilla Presley (Cailee Spaeny) from timid ’50s teenager to wife of Elvis (Jacob Elordi) to, finally, a liberated woman, using gorgeous midcentury fashions to capture an often painful journey into the heady world of celebrity.

Spanning from 1959 to 1972—one of modern fashion’s richest transitional eras—Priscilla’s wardrobe alternately includes prim ’50s skirts, poppy ’60s minidresses and swishy ’70s bell bottoms. These evocative costumes are designed by Stacey Battat, Coppola’s longtime collaborator. Battat and Coppola first worked together on Somewhere and went on to do The Bling Ring, A Very Murray Christmas, The Beguiled and On the Rocks. When it comes to working with Coppola, “There’s definitely a fluidity to the conversation,” Battat says. “We share a visual lexicon.” The director/designer dialogue follows a similar template for every movie: “She sends the script and a mood board. Based on that, I send her more fine-tuned images of the clothes, and we go from there.”

Battat came to the movie without strong feelings about Elvis’s mythology. “I wasn’t that familiar with Elvis and Priscilla,” she says. “My parents were of the age that they could have liked Elvis, but they were more into The Beatles and Tom Jones.” The film is based on Priscilla’s 1985 memoir, Elvis and Me, which, surprisingly, Battat avoided reading. “I know which things came from the book, but I know them from our script,” she says, noting that she prefers reading the script to the original source material so as to preserve Coppola’s distinct vision. While Battat didn’t speak with the real-life Priscilla directly, she was able to communicate with her through Coppola and Spaeny and found her “very insightful.” Not only did she help Battat learn exactly when she shifted from conservative to daring (“I understood through her when she stopped wearing stockings”), Presley also gave crucial intel on Elvis: “She helped me understand that Elvis always came downstairs fully dressed. It was really important to see Priscilla’s perspective of Elvis—that he wasn’t just a rock star and that he was someone that she had an intimacy with. He was the guy in bed next to her with his reading glasses. You don’t ever see Elvis in reading glasses in photographs, but he did wear them.” It’s hard to believe there are aspects of Elvis we haven’t seen, but these little details make The King seem more human.

Priscilla’s memoir describes not just her romance with Elvis but also his troubling temper and many infidelities. Elvis’s dark side manifests in the changes he demands in Priscilla’s fashion, as he issues specific rules about how she should look—in one memorable scene, he demands she dye her hair black, apply more eye makeup and not wear patterned dresses. “She didn’t gain a lot of weight when she was pregnant,” Battat says. “She ate very little because she wanted to stay Elvis’s ideal, so that was like a costume choice.” Priscilla had a huge wardrobe (Battat says she gave Priscilla around 120 costumes, while Elvis had around 90), but it was a conscious decision to make sure she didn’t have new clothes when she was pregnant. For the most part, Battat chose not to reuse many of the costumes, as the film covers so many years and dramatic changes in Priscilla’s life in just under two hours, but in this instance, outfit recycling became a narrative necessity. “We had her wear dresses that she had worn earlier,” Battat says, “so, she wore the same dress in the scene where they take LSD and later when she’s pregnant.” The sumptuous green dress captures the paradox of the ’60s, signifying both the consciousness-expanding psychedelia of the era and the oppressive gender norms that were all too common.

Elvis and Priscilla were one of the most photographed celebrity couples of their era, so Battat had a wealth of visual references to pull from. “There are historical things in our story, like when she waves goodbye to Elvis, their wedding and when she gives birth,” Battat says. “There was an effort to keep those looks pretty consistent and close to what they were.” But with Coppola’s focus on the minutiae of womanhood, there were even more scenes that didn’t have corresponding available photos of the real Priscilla. “When I think about the rest of it, it’s more about the script and period appropriateness than it is about what she actually wore,” emphasizes Battat. There’s no way to know what she wore every single day, so for intimate scenes involving trips to the hair salon and hours of bedroom lounging (a Coppola signature), the designer took creative liberties, aiming to visually express Priscilla’s emotional state while staying faithful to the distinctive fashions of the era.

Battat found verisimilitude in an unexpected place: the lingerie drawer. “A big part of getting dressed and having something feel period appropriate is getting the foundations right,” she says. “It’s not something you really think about, but a bra in 1959 is very different from a bra in 1970,” she adds, pointing out that a ’50s bra would be far more structured and padded than a ’70s one. Battat used historically accurate undergarments to create a visual narrative: “When Priscilla was younger and more innocent she always had a petticoat, which is indicative of the time, but it was a choice to have her skirt be puffier and have that silhouette that’s a little more childish than a straight skirt.” As the ’60s progress, “the puff of the skirt gets diminished; then, she moves into short shift dresses and then into pants. It’s working with the style of the time but also telling that story of how she was a girl and now she’s independent. The choice to put her in pants, the choice to have her in petticoats in the early part, created that differentiation.”

Even those with little interest in the subject likely have a basic sense of what typical ’50s, ’60s and ’70s fashions look like based on the array of reference points from the time. Given this ubiquity, it can be challenging to create period looks that don’t feel like they came straight out of a sock hop, hippie or disco Halloween costume kit. Battat avoided cliché at every turn and learned about quirky new-to-her elements of ’60s style. “There’s a scene when she’s leaving Las Vegas with Elvis, and she’s wearing a two-piece polka dot outfit that bares her midriff,” Battat says. In her research looking at ’60s magazines, “I saw an outfit like that in Vogue that had two pieces with a full, more ’50s-style skirt and a tighter cropped top. I was surprised when I saw that. I thought it was fantastic for a girl trying things out, like she got it in Vegas, and it was risqué for 1962.”

While Battat found much inspiration in contemporaneous clothing, she chose to mostly use custom-made rather than vintage pieces. “When you’re trying to be specific, it’s more efficient to create the clothes as opposed to finding the clothes,” she says. “You can’t always find the thing that you’re looking for, and sometimes it’s easier financially to just make it.” Getting the color scheme just right was particularly significant. “Sofia always said she wanted the sun to come out in Memphis,” Battat explains. “In Germany at the beginning, you have her in colors like grayish pastel pinks, and when we get to Memphis those colors become more saturated and go from pink to coral to yellow. In the ’70s you get blues and greens and purples.” These color choices come from a mix of Battat’s research (“I always go to the Met to look at the fabric library if I’m doing a period piece”) and Coppola’s poetic description of a coming-of-age story. “We’re looking at Priscilla’s inner experience growing up and trying on different identities through clothes,” Battat adds, and the changing colors indicate both the specifics of an era and more ambiguous feelings.

Collaborating closely with cinematographer Philippe Le Sourd was also key. Given the limited budget, Battat had to do sartorial problem-solving to make sure the outfits would show up on the screen just as she envisioned them. “In the Vegas scenes, we had only a small part of the room that was Vegas. It wasn’t like Philippe could turn around 360 [degrees],” she says. “I knew he wasn’t going to do a full-length shot because of the nature of what we had to shoot, so I tried to bring visual interest to the top of her outfit to let you see that she was more of an adult at that point.”

With such thoughtfully designed outfits and precise cinematography, a budget-conscious shoot hardly feels like a limitation. Each of Battat’s contributions grounds the story with looks that function as both retro eye candy and poignant portraits of a young woman caught between worlds. Priscilla is small and soft-spoken (Elvis pointedly calls her “just a baby” when they first meet), and in some scenes she looks like a girl playing dress-up. Her outfits speak when she can’t, and while they’re sure to inspire many a social media post and fashion editorial, as is inevitably the case with Coppola and Battat’s creations (her ’50s choker necklace has already been replicated as high-end A24 merch), they will also make us think of an icon in a new way. By the end of the film, we may be rooting for Priscilla to choose clothes she knows Elvis won’t like, but the decision is ultimately her own.