Back to selection

Back to selection

“We Always Sought Out Photos with Movement”: Klára Tasovská on Her “Nan Goldin of Soviet Prague” Doc I’m Not Everything I Want to Be

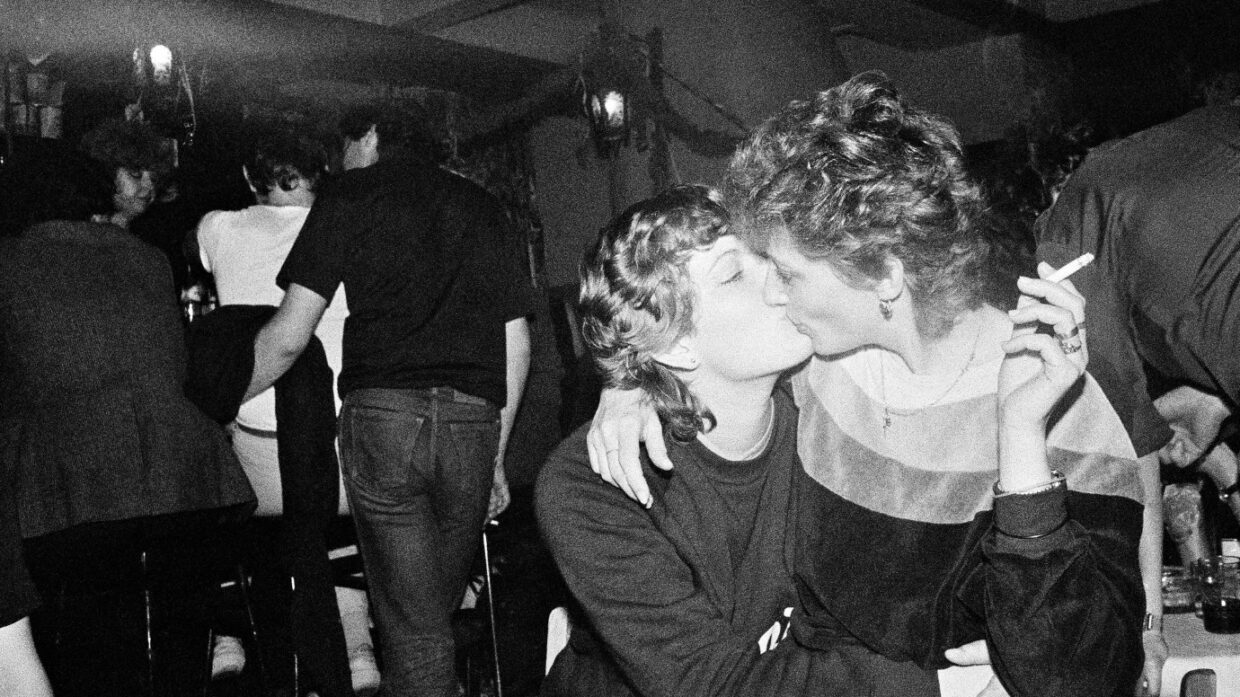

I'm Not Everything I Want to Be (Photo © Libuše Jarcovjáková)

I'm Not Everything I Want to Be (Photo © Libuše Jarcovjáková) ”The only way to survive is to take photos,” declares Libuše Jarcovjáková, the iconoclastic star/narrator/guide of Klára Tasovská’s visually arresting (and eye-catching titled) I’m Not Everything I Want to Be. Nominated for the Teddy Documentary Award at this year’s Berlinale, the all-archival film is a globetrotting, black and white trip back in time (primarily to the 80s and 90s) viewed entirely through the rebelliously inquisitive eyes of this “Nan Goldin of Soviet Prague” (in the words of curator Sam Stourdzé). And words. For not only did Jarcovjáková obsessively collect images of both her defiantly unglamorous self and her decidedly adventurous life, she kept copious diaries of that wild inner-outer journey as well.

Indeed, throwing caution to the wind, the outlaw shutterbug goes from hanging out at an underground gay club in Czechoslovakia (a country where she found herself “zigzagging through totalitarian reality”) to escaping, via fake marriage, to West Berlin. (Which “might be a step into the void but it’s a step forward,” she notes in her journal with hope. Alas, capitalism also left Jarcovjáková depressingly disoriented, unsure as to whether she was “outside or inside the cage.”) And on to Tokyo as an unlikely commercial photographer, an unsurprisingly awkward fit for a creative who’s always used her art to discover her “true self.” (In fact, Jarcovjáková much preferred returning to an unpretentious janitorial job in Berlin — camera in tow of course.)

Just after the film’s Berlin premiere, and prior to its CPH:DOX debut, Filmmaker reached out to the veteran Czech director (2012’s Fortress and 2017’s Nothing Like Before, both co-directed with Lukáš Kokeš) to learn all about cinematically capturing a larger-than-life lenser.

Filmmaker: I know that this film came to you through two Czech television script editors, but did you have to get the go-ahead from Libuše as well? Was she familiar with your prior work? How exactly did those conversations go?

Tasovská: Libuše didn’t know me and had never seen any of my films; and before we met she’d already received numerous offers for shooting, all of which she’d turned down. I think Libuše consistently relied on her strong intuition when deciding to work with me, feeling secure in the knowledge that she would be in safe hands.

Fortunately, she was quite excited for someone else to go through her archives and discover something new about her work. After I’d organized her materials into context she really became very open. She began bringing me all these boxes with the diaries she’d kept her whole life — and also discs with photos, and ultimately tens of thousands of negatives.

Filmmaker: How hands on (or off) was Libuše in the project? Did she give feedback on cuts along the way?

Tasovská: We talked extensively about the process, and I asked her about everything, but we also had total freedom in making the film.

I was so happy with Libuše’s overall trust in the project. During development we created one chapter from Tokyo, so she could see how it could work, which she liked quite a bit. Then after one year in the editing room, adding in my voiceover, we showed her the entire rough cut. She provided some interesting notes. Once we received the feedback we started to improve the texts of the voiceovers, and then finally recorded them with Libuše’s voice (which we did three times).

Filmmaker: I read in the press notes that you approached the photos as a kind of “subjective visual diary,” and that you arranged the images within five main chapters alongside the narration. What were those chapters? What exactly were you looking for? What were you less inclined to include?

Tasovská: From the beginning I’d decided that I wanted to tell Libuše’s story chronologically, as it was important to me to follow her personal development and the changes in her personality.

So I began by looking into her diaries for the plot points of the story. Each chapter represented a decision by Libuše to change her life in some way: The decision to start a new life, to leave her previous life behind and start from scratch, as Libuše often said.

The first chapter serves as an exposition of her life, depicting Libuše’s struggles in tough circumstances and her feeling of being stuck, which led to her decision to move to Tokyo. When she returns she isn’t the same person she was before, and she has to find a way to survive in Czechoslovakia before looking for ways to move to Berlin. She wholeheartedly believes that a new life will begin in Berlin, but it isn’t as easy as she thought it would be. Eventually, she moves back to Tokyo. Thus, the locations dictate the chapters.

We then tried to fill in each chapter with photos that were compatible with the voiceover. However, the first rough cut ended up being two-and-a-half hours long, so we had to remove a lot of things we really loved but just couldn’t fit into the film. Ultimately, the centerpiece of the narrative is the search for a home/safe space, which is indeed found at the end of the film.

Filmmaker: I also read that in the editing timeline you created a “fragmented motion” so that the audience forgets that we’re looking at a “slideshow” of static images. What led to this aesthetic choice? Was there some sort of rhythm within Libuše’s oeuvre that you followed (and may have likewise influenced the soundtrack)?

Tasovská: I’m very pleased that I chose Alexander Kascheeve as the editor and sound designer to work with on this film as he greatly enhanced both the visuals and the sounds. For example, the rapid montage sequences from Japan or Czechoslovakia — they are so very creative and really evoke a sense of time and place.

We always sought out photos with movement, featuring Libuše’s presence, because we wanted her to be the guide through her story and not only in voiceover. I aimed to create a very personal film that allows us to see the world through Libuše’s eyes for awhile, to experience her story alongside her. I really wanted to preserve this unique female perspective in the film. I truly believe her approach to life is very contemporary, and that her story is relevant to everyone. So it was important to bring her journey more into the present day.

For this reason we decided to use contemporary music, which likewise helped us create some very intense moments — sometimes wild, sometimes contemplative. And thanks to our mutual trust I was also able to work with entire sequences of images on the film negatives. In Libuše’s book there would be one selected photo, but we could use all the phases of a single event captured on the negative stripe.

Filmmaker: What are your and Libuše’s hopes for I’m Not Everything I Want to Be now that it’s out in the world? Do you plan on screening the film in conjunction with future photo exhibitions?

Tasovská: Yes, we have the opportunity to collaborate with exhibitions; we’ll see how successful we are in organizing such cross-platform events. All I can say right now is that we have German distributor Salzgeber onboard as well as interest from other festivals.