Back to selection

Back to selection

“All Documentary Filmmakers Should Receive or Seek Out Some Kind of Training in Vicarious Trauma”: Alix Blair on Her Hot Docs-Debuting Helen and the Bear

Helen and the Bear

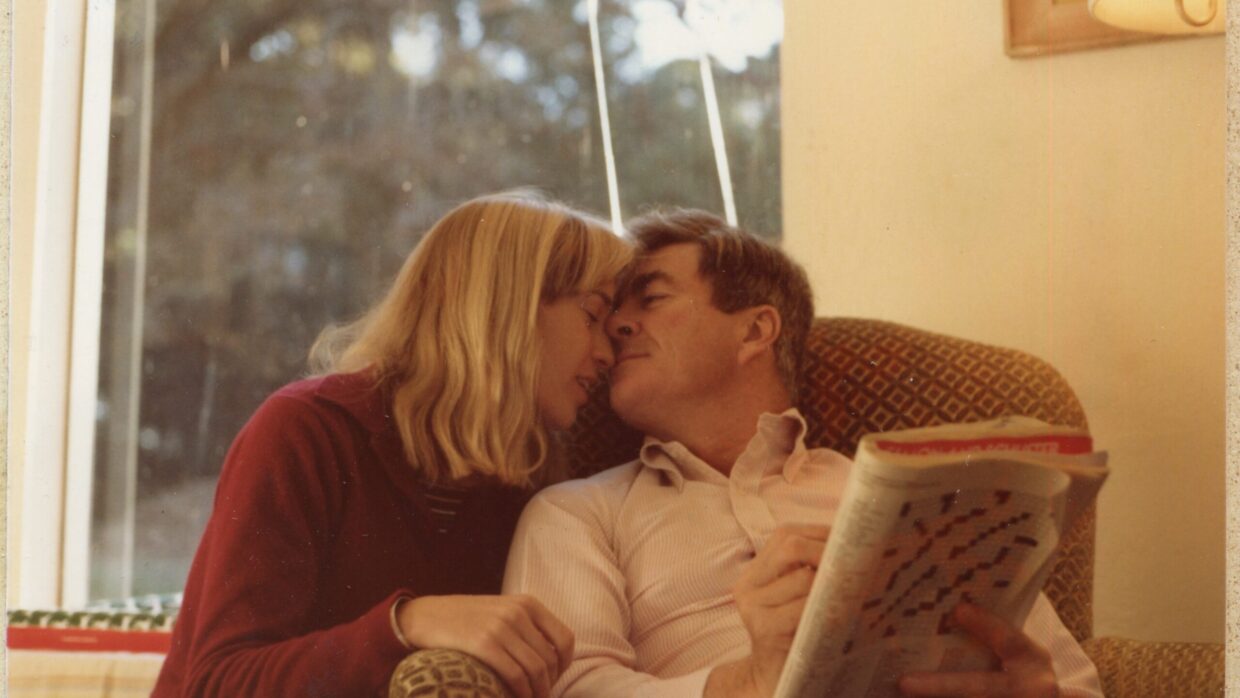

Helen and the Bear Fourth generation Californian Paul McCloskey — aka “Pete” and “Bear” — is a former US Congressman who represented San Mateo County from 1967 (when he trounced Shirley Temple in the Republican primary) to 1983; a decorated Korean War vet, who torpedoed Pat Robertson’s ’88 campaign by revealing his lies about having served in combat; and an ultimately unsuccessful challenger to President Nixon in ’72, when the maverick Stanford Law grad went on Firing Line to make the case for his anti-Vietnam War platform to an electorate likely more receptive than the program’s highly condescending, pro-Cambodia-bombing host. That particular clip from the McCloskey political archive is one of the very few that the award-winning director-cinematographer Alix Blair (Farmer/Veteran) uses in her riveting Helen and the Bear, a beautifully crafted portrait of the now-nonagenarian’s nearly 40-year marriage starring — and solely from the POV of — his even more fascinating, 26-years-younger wife (aka the director’s Aunt Helen).

EP’d by another cinematographer-director, Kirsten Johnson, this perfectly paced vérité endeavor takes us on a journey back in time (through a trove of Helen’s personal photos and journal entries) and to the present day, where the restless protagonist keeps a grueling schedule that would exhaust your average teen. Caring for both a declining Bear and their sprawling farm, which includes a virtual Noah’s Ark of critters, from cats and dogs to birds, horses, pigs and more, Helen seems perpetually in motion, even when simply “relaxing” at a bar having smokes and beers with her fellow queer friends. And yet this unapologetic iconoclast is also in a forever fluctuating state of emotion as she faces a future without her longtime love and best friend — and the very real chance that the elusive freedom that’s always been her heart’s desire might finally be her last act.

Just prior to the film’s April 28th debut in the World Showcase section at Hot Docs Filmmaker reached out to the award-winning nonfiction storyteller (and Gotham Doc Feature Lab recipient) to learn all about capturing Helen, the Bear, and the gorgeous complexities of a relationship based on a love of the land.

Filmmaker: I was quite taken with both the cinematography and sound design, which are equally compelling. So as a longtime DP (and co-founder of the Collective of Documentary Women Cinematographers) who also works in audio, how do you think about these two aspects in relation to one another? Does the image come first for you?

Blair: Thank you for this lovely question. I certainly think of sound and image as deeply interconnected. I am grateful to my many years of working in audio production as it trained me to be a storyteller who did not rely only on my eyes.

In audio of course you cannot depend on visual descriptions alone to tell your story, you have to have a way to see with sound. It feels obvious perhaps that the image might be more important in the hierarchy of sensory information in a film, but this is not true. While I have to of course put my heart and attention into the little rectangular screen of my camera because that’s what I owe my audience, I am always deeply aware of what my ears are hearing; and many times it is my ears that tell me where to point my camera.

You reference the sound design, and I was blessed to work with the incredible editor Katrina Taylor, who, as she meets a project for the first time, creates a playlist for each of the characters. It was one of the things that made me recognize that she was the right editor for this collaboration. She is insanely talented at finding the right song for the moment. And with that foundation we partnered with Troy Herion and J.R. Narrows, who collaboratively built our score and our sound design into the beautiful sonic world you get to experience in this film.

Filmmaker: When did your EP Kirsten Johnson become involved in the project? Did she provide specific creative guidance?

Blair: If you had told me at the beginning of this project that I would be working with Kirsten Johnson I would not have believed you. It’s such a cliche statement, but I still can’t believe that I get to work with her; she’s one of my absolute heroes of documentary film – as a director and as a cinematographer. I think I’ve watched every workshop she’s ever put online, read every interview, listened to every podcast. She is one of the most creative filmmakers out there and, as I have come to learn, one of the most generous human beings on the planet.

I approached Kirsten about being a creative advisor on the project after my co-producer Elise McCave connected us. Kirsten did provide specific creative guidance and troubled the story with me over many months. She challenged me in all the best – and hardest – ways. She asked the questions that I wasn’t ready to face and held my work with such genuine and joyful curiosity: “Try this! What if you told it this way? What if you moved this part to the beginning?” Working with Kirsten made me fall in love with my own work in a way I didn’t anticipate. She is that kind of a teacher. (Still I was so nervous to ask her to be an EP. I think I wrote and rewrote that email so many times. And she said yes!)

Filmmaker: In your director’s statement you write, “I have witnessed how memory lives within us as ghosts of all our former selves and to achieve this emotional truth I have worked with multiple temporalities of footage and with Helen’s diaries kept over decades.” At what point did you make this creative choice, and how did it affect the editing process?

Blair: When Helen offered to share her diaries with me I knew immediately that they would be part of the film. No matter what they would have a place. I just wasn’t sure in what form. Katrina and I went through many iterations of this, even before working with our animator Emily Ann Hoffman.

Helen’s diaries are so vital to the story because they capture her living emotion at the time of writing. In interviewing Helen and Pete in the present about the past, the intensity of their relationship’s struggle isn’t apparent in the way that is so primal in the diaries. Through her words you feel her anguish, her confusion, her doubt. It’s just not possible to access that 20, 30, 40 years later in an interview; and so the diaries act as a time portal, as a ghost, to connect with Helen’s past self.

Filmmaker: Your first feature Farmer/Veteran follows an Iraq War vet who finds healing in farming, as does Helen. So what draws you to these twin subjects of trauma and agricultural life as filmmaking material? How do they connect?

Blair: There was a moment in making Helen and the Bear when I was like, “Oh my gosh, I’m making the same movie! What am I doing?!” Which of course isn’t true, as they are very different films for many reasons. But as you thoughtfully point out in your question, my curiosity about how we process trauma and how we find healing is present in both of them. There is a lot of research that points to how human beings find healing in nature, that connection to the natural world — in this case the agricultural world — which offers a sense of belonging and meaningful relationship.

In the years I worked on farms I felt it absolutely — the care-taking of growing things, the accountability to other creatures, the joyful feeling of having grown something that you are now cooking to eat and share with friends. But there is danger in romanticizing the relationship between nature and trauma, with farming specifically, and this comes through in both films. Both the veteran and Helen feel the tremendous burden of care-taking animals and land without the resources available to them to be successful. I want to challenge the assumption that rural life is automatically idyllic. That said, I profoundly believe that building kinship with the natural world is a path towards healing.

I would also add that a third theme that runs through both films is how we love and how love is messy and complicated.

Filmmaker: Your bio mentions that you’re also a “researcher and speaker on vicarious trauma in documentary filmmaking.” What exactly does that entail? What has your research uncovered?

Blair: I will preface this by saying I am not a therapist nor a social worker. But my own lived experience and research has informed my opinion that all documentary filmmakers should receive or seek out some kind of training in vicarious trauma so that they can anticipate it, and know the signs when it appears in their own bodies and lives.

Vicarious trauma, also called secondary trauma, is when you are emotionally and physically impacted by the traumatic experiences of the people or places you are exposed to — in this case by documenting their lives. The making of Farmer/Veteran is what led me to be curious about this phenomenon. I did not go to school for filmmaking and, like many independent documentary filmmakers, did not have clarity about the emotional toll that documentary filmmaking can take on the maker. You are bearing witness to other people’s lives. You are seeing them sometimes at their worst — in their sadness, in their rage — and you are asking them questions that trigger trauma and painful memory. I think the very skill that makes you a good documentary filmmaker, that sincere empathy, is also the very thing that makes you so vulnerable to vicarious trauma because you feel it. Every time I give a lecture on vicarious trauma to documentary filmmakers there are so many reactions of, “Oh my god, that’s my experience!” from the audience. I’ve learned to make my Q&A time longer and longer, to make space for people processing their vicarious trauma in real time. “I’ve stopped sleeping” and “I feel guilty that I can leave and my subjects cannot” and “I’m having nightmares based on stories from my interviews” — these sentiments are all parts of vicarious trauma, and there are practical ways to interrupt the damage it can do. I think the most important thing is to be able to recognize it when it’s happening,rather than assume it’s a normal part of documentary work or that something is wrong with you.