Back to selection

Back to selection

Shutter Angles

Conversations with DPs, directors and below-the-line crew by Matt Mulcahey

Holding the Chicken: DP Rob Hardy on Civil War

Civil War

Civil War In Civil War, the United States has splintered into four clashing factions, but if you’re expecting a treatise on the country’s ideological divide from British writer-director Alex Garland, this is not that movie.

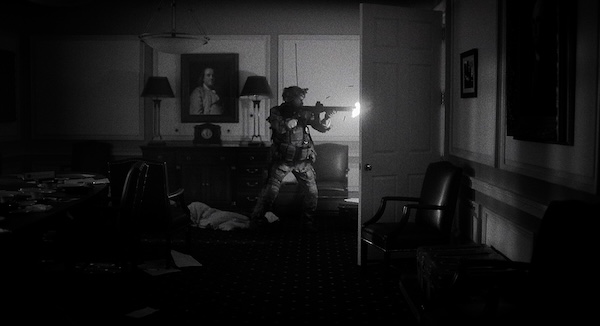

America’s dysfunction is secondary to examining the toll on the journalists covering the conflict. The story follows a quartet of correspondents (including jaded photographer Kirsten Dunst and green Cailee Spaeny) as they travel to the war’s front in Washington D.C. in hopes of landing an interview with the embattled president (Nick Offerman).

Cinematographer Rob Hardy, who’s lensed all of Garland’s projects since the novelist/screenwriter turned to the director’s chair, spoke to Filmmaker about shooting A24’s most expensive film to date.

Filmmaker: Tell me about the logistics of making Civil War. You filmed mainly around Atlanta, and you built some of the Washington D.C. sets in a parking lot in Stone Mountain, Georgia, which is about thirty minutes from Atlanta. What’s the furthest out that you traveled for this road movie that makes stops in New York, Pennsylvania and West Virginia?

Hardy: In terms of prepping the show, we went up to D.C. and there was a little bit of B-roll done there. There was a bit of B-roll in New York too. The shoot proper was, as you say, in Atlanta. I think the furthest out we went was probably Stone Mountain. When we shot Annihilation, we did a sort of trippy version of Florida within an hour’s drive of London. I figured if we could do that, we could manage the Eastern Seaboard version of the U.S. in Atlanta.

Filmmaker: You also shot very close to in sequence. That’s a bit easier on a road movie like this, where you are really only shooting each location once. Why was it important to you and Alex to capture the story chronologically?

Hardy: It’s a practice that Alex and I have always adhered to in the sense that we think that shooting chronologically—as far as possible, notwithstanding logistics—makes complete narrative sense on so many levels, especially in the road trip context. So, it wasn’t our first rodeo as far as the chronological aspect was concerned. We felt that it added to that sense of journey, building up to this big climax. And like any kind of road trip, you can go off on tangents and that allowed us to riff on a specific location if we needed to before moving on. Plus, by the time we got to the end—the big siege in D.C. on the White House—you could feel the exhaustion, specifically within the cast, and that only played to everybody’s advantage. You really felt like we were all in it together and taking that journey all the way up to the Oval Office together. I understand why things are not shot chronologically most of the time, but there are other times when if there’s a will to do it, it is possible, and the movie only benefits from it. Everybody benefits from it. It gave my team time to prepare for some of the bigger set pieces in the film that were towards the end. It also gave me time to develop the story visually. You learn by your mistakes because there’s always going to be things that you’re going to try and then discard as you progress. Civil War, particularly by the way it was constructed narratively, allowed us that space to grow and react. So much of the show was about allowing a degree of reactiveness in real time.

Filmmaker: I’m sure this is going to get brought up in every interview you do about the film, but let’s talk about your use of the DJI Ronin 4D on Civil War. You used the 6K version, right, because the 8K wasn’t out yet when you shot?

Hardy: Yeah. Even the [6K] was a relatively new piece of kit. I think it’d been developed for the prosumer market. Alex and I were having a lot of conversations about our approach to Civil War whilst in postproduction for Men. We knew that we wanted something that was going to allow us to have our moments of elegance, our moments of abrasiveness and also allow us to be immersive in a way that enabled the actors and everything else—the military machine of it all—to do its thing without the cameras infringing too much.

We really wanted this idea of capture. Our first port of call in terms of references was newsreel footage. I’m not talking necessarily about the aesthetic of newsreel footage; what I’m talking about is the sensation that watching newsreel footage gives you. It’s quite common these days in a war zone for someone to literally be using their mobile phone to film something and then outside of that frame an explosion happens, or some terrible event happens that is half-captured. You get this sensation as you’re watching it that there’s an unpredictability to it. There’s a sense of tension to that, this idea that anything could happen at any moment, and we wanted to really fuse that idea into the narrative.

We’ve used Steadicam a lot in the past. We’ve used all of the tools that filmmakers use [to move the camera], like the Stabileye, and liked all of those things, but didn’t want those for Civil War. With the Ronin 4D, the cameras became quite invisible, which allowed the actors to feel the environments that we created that much more. Every time Alex and I prep a film together, it’s always about the environment. That’s our starting point. What is the world? What does it feel like? We try to authenticate that as much as possible when it comes to the lighting and everything else. I’m trying to create 360-degree environments that the cameras can enter, a bit like in a recording studio. If you mic a band in the correct way, the way the room sounds creates the sound of the band playing live. The cameras are essentially just microphones, and if you position them correctly, you’re going to get the best sound possible. What’s also great about the Ronin 4D is that, whilst you have this idea of an operator holding the camera, I could control the frame remotely. So, I’m on the wheels and controlling exactly what the camera is seeing.

Filmmaker: With the 4D, is it correct that you can dial in the level of smoothness? Was that one of the reasons you wanted that tool as opposed to another gimbal?

Hardy: Correct. It has this ability to give us more than one aesthetic in one piece of hardware. It could operate like a Steadicam or you can lock the head so it becomes more like handheld. You can dial that in to a degree and it gave us a huge amount of flexibility. I’ve always described it as like holding a chicken. I don’t know if you’ve ever held a chicken…

Filmmaker: [laughs] I have not.

Hardy: If you’re holding a chicken by its body and you’ve got your hands on either side of it, holding its wings in place, and you’re walking along with the chicken, the chicken’s body might be going up and down with the movement of your walking, but its head stays in the same place. That’s basically the principle.

Filmmaker: And you had six of those cameras?

Hardy: Yes, six units in addition to our main package, which was the Sony Venice. I had a bunch of these H Series lenses from Panavision for the Venice. They have a beautiful look about them. There’s something otherworldly about them without being over the top. They are very elegant. For the 4D element of it, each unit had a different focal length attached to it, because you would have to recalibrate the camera [every time you changed the lens]. So, camera number one would be the 21mm camera, number two would be the 28mm camera, number three the 35mm and so on. When the 4D was first released there was a very short list of lenses that you could use on the camera that would balance properly, but most of those lenses—in fact, all of them—felt sort of off-the-shelf in style when we went through them during prep. I needed something that was going to stand out visually. What we came up with through testing was the Leica M 0.8 lenses, which originally were stills lenses. We had Panavision put gears on them, then I had Dan Sasaki at Panavision detune each individual focal length to match as close as possible to the H Series lenses, so that I had a consistent look across the board. We basically had an arsenal of lenses and cameras that we could use at any given moment. I operated A camera, as I always do on any production that I work on with Alex. Then I had a B camera and C camera that were full time. We also had a D damera that would fold in for the bigger set pieces.

It doesn’t end there, though. We also had a bunch of Sony a7S cameras that we used for what we called our “coverage car.” We had three vehicles total [for shooting the hero SUV]. We had a pursuit vehicle with a U-Crane Arm. Our second vehicle had a pod on top for the stunt driver so we could be inside that vehicle and shoot in any direction for a lot of the action stuff and the actors wouldn’t need to worry about driving. Then our third vehicle was what we called, for want of a better word, our “coverage car.” At any time, that car had 12 to 15 of these Sony a7S cameras attached to it, the idea being that the actors could jump in and drive, because there’s a lot of dialogue inside that vehicle. From inside the car, you had all angles covered. From outside the car, specifically for Cailee and Kirsten, we could get those lovely reflective shots where we see their face but also see the landscape passing by. We used that vehicle to cover us for any of those long driving sequences, after which we would then go in and cover more details in the free driving or the pod car.

Filmmaker: Throughout the film we see the photos taken by Cailee and Kirsten’s characters. Who actually took those photos? You used a Red V-Raptor shooting at a high frame rate for some of them and then just pulled frames out of that footage.

Hardy: Cailee would take her stills on [her character’s] Nikon using black and white film. So, we would pull stills that she was taking literally from her camera. I would take some stills, Alex would take some, our stills photographer would take some. Kirsten’s camera was a digital Leica with a 35mm lens on it and we would take images from that.

The whole inspiration when we first discussed what those images would be was the idea of what happens when a photographer lifts the camera to their face to take a picture and that millisecond of a moment is frozen. If you look at that millisecond of a moment, it’s almost like you reverse engineer it from there. What was happening outside of that frame? What happened in the moments leading up to that still image? What happened in the moments after it? How do we approach that aesthetic? How do we build the world around that? That informed the whole aesthetic of the movie, but it also informed this idea of, how do we capture those moments [in still frames]? We decided that one of the best ways to do that was to shoot at an extremely high frame rate [on the V-Raptor], then we could capture those moments as the camera is coming up [to the photographer’s] eye to take the image. Then we could analyze every single frame—well, not every single frame, because that’s a lot, but we could find the exact moment that we needed rather than taking a bunch of stills or shooting at a regular frame rate. We were basically hedging our bets a little bit. You know, why take 25 frames when you can have 200 or 300 frames?

Filmmaker: What did you set your shutter to on the Raptor in order to pull crisp images from the footage?

Hardy: If my memory serves me correctly, I’m pretty sure what we did was shoot with a 45-degree angle shutter. It made every frame that much sharper, which then brought it into a sort of stills photography aesthetic.

Filmmaker: So, you did the Saving Private Ryan shutter angle to make everything crisp.

Hardy: Yes, it is known as the Private Ryan shutter angle since that movie came out, because it was never used before. [laughs]

Filmmaker: Point taken. [laughs] I was watching a western from the 1950s the other day and they used that shutter angle on a horse chase scene to liven things up. But, yes, I still call it the Private Ryan shutter.

Hardy: Well, it is a masterpiece of cinema.

Filmmaker: There’s a moment just before the journalists reach the front lines where they drive through a forest fire and the embers of that blaze fall all around the car. I saw a behind the scenes video of that scene and there was basically a truck in front of the picture car wafting embers onto the road. That reminded me of the bit at the end of The Natural, shot by Caleb Deschanel, where all the sparks are falling on the field.

Hardy: That idea was developed originally when we were doing Devs. There was a sequence inside a cave where we saw a cave painting being done in real time. Within that sequence there was a fire inside the cave and Alex and I ended up spending a lot of time on a stage in Manchester shooting embers. We really got into it, to the point that I think we were pulled away and reminded that we still had a bunch of really important scenes to shoot. (laughs) We become quite elated by this slightly surrealistic moment and that’s a thread through all of the work we’ve done together, I guess.

Civil War was no exception. Even though, for the most part, it inhabits I would say a quite realistic aesthetic, we still wanted these moments of beauty. So, yeah, we’d had some practice with the embers and, with anything, if we’re dealing with VFX we always like to embed a lot of real elements on camera and then build on those [in post]. That comes from the very beginning [of our working relationship] when we shot Ex Machina, where we didn’t use any greenscreen. We had Alicia Vikander in a real suit and then everything was enhanced or augmented later. So, when it came time shoot the embers on Civil War, we’re like, “What’s the best way we can do this?” Well, we’re going to get a truck that we can just throw embers off, because it looks great. Look at the way those embers hit the tarmac and look at the way that the embers fly through the air. We needed to shoot that. There’s nothing that’s going to look better than that.

Filmmaker: Let’s finish up with the Jesse Plemons scene, where the journalists come upon a group of men dumping bodies into a mass grave off of an isolated country road. It’s been pretty well documented that Jesse stepped in for another actor at the last minute since he was already in Atlanta with his wife, Kirsten, for the shoot. Did you already have that scene shot listed? Did you change your approach once Plemons got on set and you saw what he was going to do? The coverage for that scene is longer lenses with the camera further away.

Hardy: For the most part, it’s very true to say that we don’t shot list until the day, because we’ve prepped everything so well that we’ve enabled ourselves the freedom to allow the actors to decide how they want to do it, then we react to that. We’ve given ourselves enough space around the environment in order to free us up to basically put the cameras wherever we want. So, we’re walking into that day with that in mind and Jesse brought to it the brilliance that he brings to everything he does. Before we started shooting, Jesse was speaking to Alex and I about the scene and he had this little bag with him. He opened it up and said, “I’ve got some sunglasses I want to show you guys.” He had maybe six or seven pairs and one by one he was putting them on and waiting for us to react. And we were like, “Okay, next. Next. Next.” The he gets to the second to last pair and they’re these very cool mirrored sunglasses. And we were like, “Yeah, that really works.” Then he just slightly turned to walk away, but then he said, “Oh, wait, there’s also these.” And he pulls out those red sunglasses. It was the perfect way to enter the scene for all three of us—for everyone involved, really—because it’s like, we know where this is going now. We know exactly what kind of person he’s going to be and we need to approach this scene the same way that [the reporter played by] Wagner Moura approaches it—very, very carefully, from a distance. We were going to shoot long lenses and be very compositionally calm with the cameras. It was almost going to be the quietest moment in this crazy road trip. Everything else up until that point and everything else that follows, aesthetically, is pretty immersive and the audience is thrown into these sequences with nowhere to hide, whereas for that scene you just needed to observe and watch Plemons in those rose-tinted glasses.