Back to selection

Back to selection

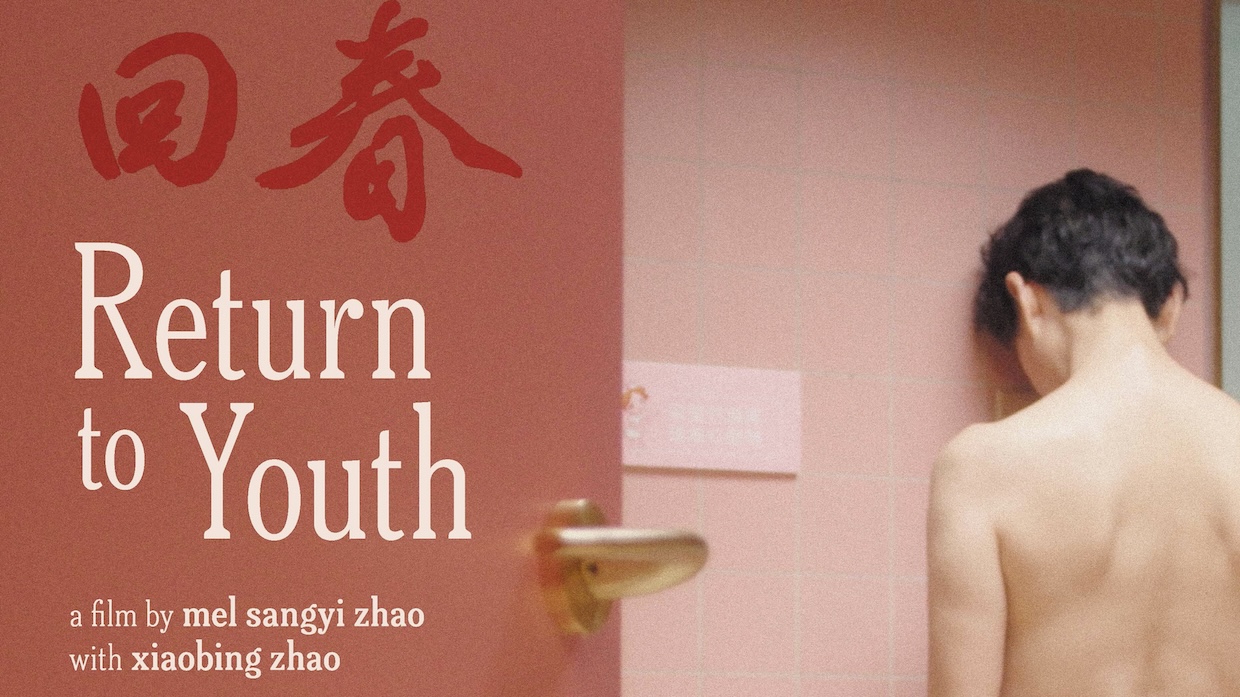

The Gotham Pages: Mel Sangyi Zhao is Creating Space for More Complex Women Characters

Cinema often shrinks from women’s middle age, a site it seems to find either innately unglamorous or melancholy. Middle-aged women are frequently relegated to supporting figures, particularly in tales of girlhood, but there exist so few accounts of their lives on screen. For this reason (and so many intersecting others), women are primed to dread middle age, for few truly know what to expect of it.

Return to Youth, the daring short from ascendant filmmaker and Gotham EDU alum Mel Sangyi Zhao, places itself squarely in this long untapped cinematic space. Perhaps unsurprisingly, women directors generally seem more inclined to cover what happens after the coming-of-age, after falling in love and then falling out of it. In fact, Zhao’s film was inspired by a conversation she had with her mother, Xiaobing Zhao, who stars in the film as Bing, a spirited former dancer in her fifties, forced to confront her anxieties about aging, beauty and loneliness, which sets the stage for her impulsive embrace of newfound sensual pleasures after her masseuse suggests vaginal rejuvenation surgery.

Zhao’s incisive and assured 17-minute portrait, the young director’s MFA thesis film, earned her a place alongside four other winners of the fifth annual Focus Features | Jet Blue Student Short Film Showcase, a Gotham EDU initiative through which films are selected by a special jury of curators, critics and filmmakers. The Gotham has long supported independent cinema, and this program specifically champions a diverse group of emerging filmmakers: Winners each receive a $10,000 grant and the chance to have their film screened on Focus Features’ streaming platforms and JetBlue flights. Further, The Gotham supports the Showcase’s awardees with ongoing industry mentorship and film workshopping opportunities.

Zhao, who is originally from Chengdu, the capital of China’s Sichuan Province—where she shot Return to Youth—has lived in Paris and Los Angeles, and is now based in the Midwest, where she teaches filmmaking at the University of Missouri in Kansas City. I had the opportunity to sit down with the filmmaker and talk about working with her mother, translating feminism in person and on screen, and situating herself outside the Western film canon.

Kelli Weston: Can you describe being part of the Gotham Showcase and how it felt to be recognized in that way?

Mel Sangyi Zhao: I missed the Gotham event due to visa reasons, but I was really surprised I got selected. Normally, short films need to be striking to make a wave; I consider mine to be a bit more of a slice of life, almost underwhelming. It does feel like a huge encouragement to me that something that is this culturally specific, raw yet gentle, could be selected for such a prestigious event. It gives me some hope that the industry does and could have a place for films that are more “underwhelming” and small. And I think for my mom, it is also a big validation, which she never thought she would have in her sixties.

KW: How did you convince your mom to star in this film? And what was it like to direct her?

MSZ: There was barely any convincing because she was a dancer throughout her life. She is a performer herself. Before I was born, she was actually trying to become a film actress. She did local TV shows and movies and stuff. But you know, she’s not shy in front of the camera. She isn’t really in the industry, but it’s not like I’m asking somebody who has never performed before. You know, this is such a big part of my life, and I talk to her constantly about the stuff I’m making. So it just felt kind of natural when this came up. I think the fact that she was acting for her daughter’s thesis film maybe took the pressure off of her. And since I wrote it for her, there were a lot of times where direction wasn’t even needed. Obviously, I will fine tune certain rhythms, but the general direction was made before we even got on set.

KW: She also has to be really vulnerable in certain scenes—for example, when she’s naked and when she’s lying in bed with her young lover—but she seems so confident and natural.

MSZ: I’m glad it comes across that way. But during filming, those were the moments where there was a bit of tension between us. We first saw it in Norway together with a very white audience. And then we had a long conversation about what feminism means for me, which was hard because I don’t even have the language in Chinese to talk about certain things. So I had to find the language. Sometimes I actually had to Google stuff. Like, How do you say “cultural appropriation” in Chinese? And those were actually the really valuable results for me of this film. She was able to see me more as an artist, not just her daughter making films for film schools.

KW: You’ve made a couple of shorts before this one. What do you generally start with in the filmmaking process? Is it an image or a conversation that usually inspires you?

MSZ: So recently, I actually had a conversation with somebody. When I make a film, it feels like cooking, especially the type when you are in the middle of the week, you didn’t go grocery shopping, you have some random ingredients left; what do you do with it? You have to eat. So for me, filmmaking has always been like that. I don’t have money and I have a story that’s right here: How can I make this work for this? It’s always kind of starting from the ingredient. I don’t think I’m a visual person in the sense that the image speaks to me, but it’s really the emotions that speak to me. There are moments in my friend’s life or in my own life, [when] I will experience emotion and I remember that moment and it will end up in a film. And then everything else—the sound, the visual, the color—they have to work for that, not the other way around.

KW: How has your relationship to the medium developed over time, from when you wanted to be a filmmaker as a kid to now as a director?

MSZ: I started out with a very canonic, Western film history education. Most of the films I watched were European masters. The little bit of Asian cinema I would get in touch with was very old Japanese cinema that I do not relate to at all culturally. And at that point, I was like 18, 19. I was running away from home; I was running away from where I grew up. I just hated the whole culture in my high school—that you have to go to a university, find a job, get married, have children. No, no, no, no, no, no—I wanted to run away from all that.

And I think through getting in touch very intensely with European culture, there was a lot of effort on my part to assimilate into that. And then slowly, after a few years, especially after coming to the [United States], [that experience made] me relook at French culture. I arrived in the U.S. at a very politicized time, in 2019. The next year, we had COVID and we had the Black Lives Matter movement, [which] was kind of like the starting point of my modern racial, political education—of understanding, oh, you cannot get around race, even if you’re here assimilating. In Western culture, they do not treat you the same, they do not look at you the same.

And from there, my relationship to film started to change. It was not just about looking at pretty images. Because a lot of the European films I used to like are very self-absorbed. Like Éric Rohmer’s characters are very middle-class, bougie, Parisian, self-absorbed young people, although I am able to identify with a lot of those emotions there. But I’m starting to see how, oh, they come from a cultural context where they’re really about themselves, whereas I am a person of color.

And then, with those white people who control the industry, you will hear these discourses all the time, right? “Oh, this person is representing Asian cinema” or “This person is representing African cinema.” I have to carry the burden of representation. If I’m not representing my country or race, then I have less value. Why is it that, in my work, you’re trying to always detach me from my individuality?

What I want to do is tell a story that I care about. I want to showcase the human beings that I see, the beauty in their emotions. I want to show that to you as authentically, as honestly as possible, without trying to cater that to some sort of political discourse. And I think by doing that, I’m actually being more political. I’m actually being more transgressive.

KW: Can you talk about your next project?

MSZ: The next film is directly coming from those conversations I had with my mom after Norway. So I’m going to do [another film] with her, and this time I’m going to act with her. The story is a fictionalized version of the making of Return to Youth. But I set it in a Western world among a majority white crew to be able to talk about my reflection on how we can all be feminists, but in very different ways. The director who’s my character has a white boyfriend, a producer. How does that clash with the expectation of you being an Asian woman, making a film in the Western context?

The feature is going to be a little bit more ambitious and [will] talk about the power dynamic between the person in front of the camera and behind the camera. Is there any way to achieve true equality? And through that, it’s going to be more about my relationship to the medium because I think I connect with people a lot through film. And for me, there is a lot of frustration and loneliness in there when you realize, oh, you’re the only person upholding that vision. So I think the feature version will be a bit more ambitious in terms of talking about what it means to make a film. What does it mean to collaborate while you are actually the leader? How does the power dynamic actually work when people are doing such an intense piece of work together?

Mel Sangyi Zhao’s Return to Youth is now streaming on Focus Features’ YouTube channel. Follow her on Instagram @angrybird_mel to stay tuned about her next film.

Community News

Updates, premieres and other highlights from The Gotham’s vibrant community of film and media makers.

Barento Taha—a Gotham EDU summer ’21 alum—celebrated the world premiere of his short, Nagaatti, at the 2024 Miami Film Festival.

Nagaatti sits with a young man’s struggle to replicate his mother’s recipe after her funeral. Sounds and smells fill the empty home, eliciting old memories of her—some warm and comforting, others perhaps best left forgotten.

Barento Taha is a filmmaker from Columbus, Ohio. He’s currently based in Los Angeles and attends USC’s Film & TV Production MFA program, through which he was awarded the prestigious Jack Nicholson Award in Directing.

Chris Molina, a shorts programmer for the Miami Film Festival, also celebrated the world premiere of his first feature, Fallen Fruit, at the festival. Chris participated in The Gotham’s 2022 Career Development EDU program and is a former MTV Joel Schumacher & Sophia Cranshaw Scholar.

Fallen Fruit follows Alex (Ramiro Batista), who begrudgingly moves back to his childhood home in Miami from New York. Blinded by his optimism, Alex underestimates the hurricane that is adulthood and begins documenting his rock bottom with an old camcorder found in his childhood bedroom. He soon finds comfort in Chris (Austin Cassel), who shows him what a life in Miami might have to offer.

Chris Molina is a Miami-based filmmaker whose work focuses on queer stories, often blending fiction and autobiography. In 2022, Molina was named Best Film Director and “a marquee name in South Florida’s film scene” by the Miami New Times. His debut feature, Fallen Fruit, premiered at the Miami Film Festival in 2024 and received the Audience Award for Best Feature at the OUTShine LGBTQ+ Film Festival. Catch its next screening at Frameline Film Festival in San Francisco.