Back to selection

Back to selection

“The Contingency of the Image Is Its Truth”: McKenzie Wark and Jessica Dunn Rovinelli on Life Story

>Life Story

>Life Story McKenzie Wark is out in Brooklyn, New York. We’re speaking via video chat in the days leading up to the FIDMarseille premiere of Life Story, her new collaboration with Jessica Dunn Rovinelli. Between questions, and while we wait for Jessica to join us, McKenzie moves around the world just out of frame. She speaks to her daughter, walks into and out of L-Train Vintage, crosses streets, occasionally exchanging greetings with passersby. It is a joy to edit the transcript of this interview later on—sentences are punctuated with “oh hi!”s, “how’ve you been?”s, little subtexts of intimacy smuggled into thoughts about art and life-making.

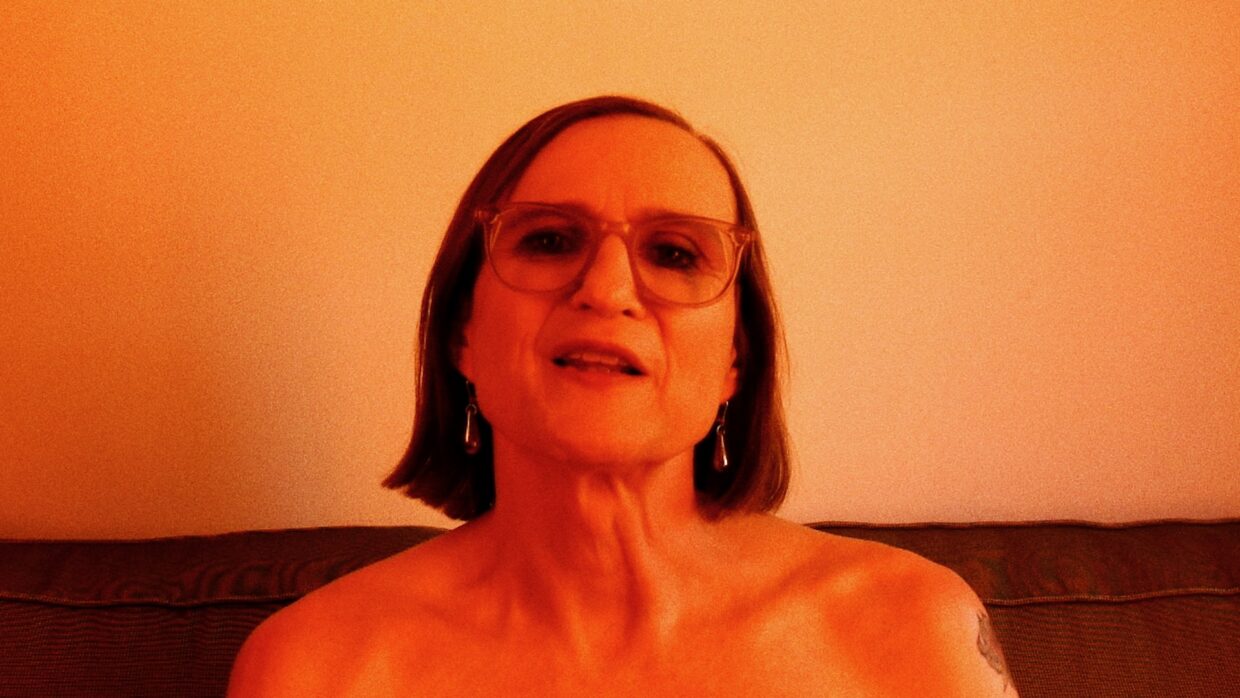

Rovinelli’s Life Story is a monologue to camera, sort of. Over the course of the film’s ten minutes, Rovinelli focuses it on Wark’s body. The audio begins and ends with Ne/Re/A’s “In the Dark”, a club track that matches the moves of Rovinelli’s photography: immediately inquisitive, tenderly exposing. Life Story contains a gradual color gradation, a kind of slow siren between a “realistic” image and a super-orange hue. The film has a heartbeat, a heat. It’s a little voyeuristic, but any eroticism is closer to the body as observed-observer, a beat away from Wark’s 2023 book about the NYC techno scene, Raving. There’s pleasure being taken, in photographing a friend, in showing a trans body as a thing with a past and future, in asserting the older female body as a glorious image.

After the film’s premiere, Life Story won the festival’s Alice Guy Prize. I spoke with McKenzie and Jessica about intimacy in art-making, creating friendship, and the connections and life-stories that feel uniquely possible inside of cinemas.

Filmmaker: Can you point to any single moment that Life Story originates from? Was it maybe when your friendship with Jessie synced up with the idea for artistic collaboration?

Wark: I’ve known Jessica since 2019. We met just after the So Pretty premiere, and we’ve been close since then. Jessie was my trans mom initially—I think we’re each others’ mom at this point. Jessie made a short film called Marriage Story, and the idea was to do a series of these roughly ten-minute pieces and then eventually put them together. I don’t know whose idea it was. I just seemed like a thing that was naturally going to happen at some point. We’d figure out how to work together, preferably in a sort of small, contained piece, working with people we were close to.

Filmmaker: Did the text come first? Or did it come as the film was coming together?

Wark: We talked about it as a monologue piece. There were certain formal properties that carried over from Marriage Story: that film had a sex scene, and a monologue, and making coffee because there’s always someone making coffee in Jessie’s films. For this one, I thought, “No I don’t wanna have sex with my girlfriend, I’m not even gonna ask her about that.” She is in it briefly—she passes across the screen. And it’s tea instead of coffee. And monologues. [I thought], “What specifically about a monologue to camera, in the context of film, do I want to do?” That was the thought process from that point on.

Filmmaker: It feels like an underutilized technique in film. Or maybe just one not used as intentionally as it used to be, or still is in theater.

Wark: The monologue? Yeah. Orson Welles has an amazing one. There’s an amazing Elliot Gould one, where the character knows he’s under FBI surveillance. The model, though, was Guy Debord. I was thinking about Debord’s In Girum Imus Nocte Es Consumimur Igni. He was such a singular person, you know? You really can’t imitate that style. So it was: “Oh, how can you make that your own?”

Filmmaker: Do you have much of a relationship to speaking your writing aloud?

Wark: There are two kinds of writers. There are writers who really like to talk and writers who don’t want to talk at all. And I’m the talky kind. I like performing my stuff, and I’ve thought a lot about how to write for the voice. For my voice, which is tricky because I’m between accents, and I haven’t done voice therapy since I came out. This is still the same fucking voice. So, I just sort of went into it. And there’s a cadence to this Mid-Pacific, Australian-American dialect nonsense that just sort of…it’s what I do. I think about that a lot. And it was sort of a pleasure to get to do that on film. I think we did maybe two takes, because I just broke down, after a point. I couldn’t…you know, I was just crying after a while.

Filmmaker: You hear that in the film, right? Especially when you’re talking about your kids.

Wark: I’ve kind of written about several people that I’ve loved. I don’t want my kids ever to think that they were less important. It’s like, “You’re not in my stuff because you’re more important.” And, also, I just don’t think it’s appropriate as parents to be telling their stories. They don’t belong to me.

[Jessica joins the chat]

Filmmaker: Jessie, we were talking a little about the origin of the film, and McKenzie mentioned how there was maybe a natural feeling to doing a film like this together. How has an intimacy among friends and collaborators informed your filmmaking to date? How do you think about intimacy in terms of filmmaking?

Rovinelli: With every film at this point, I’ve come to realize it’s very hard for me to get away from doing anything else, except for something that engages very directly with this intimate connection between myself and the subject, between the camera and the subject. I think it’s a process on set. It’s a process in talking about the film. One of the best ways to generate intimacy—which is probably true outside of film—is giving someone clear notes and guidelines while being very responsive to their feedback, [and] not pushing where they get cranky. It involves being very rigorous in certain elements so that you have a frame where certain things are secure enough that you can safely move forward. The aesthetics of the film are very locked in. And then, of course, in this case, McKenzie was so gracious as to let us get very close to her body. It probably helped that this was not the first time I’ve photographed her.

Filmmaker: Has that been mostly still photography?

Rovinelli: I’ve taken a few shorts for magazines of her. And then, you know, I’m just constantly photographing, and McKenzie is always around. She likes being photographed.

Wark: I do like being photographed.

Filmmaker: I thought some about Double Strength, the Barbara Hammer film, in the way the camera moves across the body, seizes on the pleasure of seeing the body from an intimate angle. There’s such a warmth in this film.

Rovinelli: That’s why the films are supposed to be screened in cinemas. I don’t want them on streaming because I like the idea that you have to be with other people to have that connection. The film is trying to facilitate a chance for someone to encounter McKenzie in a way that is not the same but related to the way that I get to encounter McKenzie.

Filmmaker: McKenzie, for your part in tending that intimacy, is it easy to give up some authorial control? Does being a photographed subject feel different from being the author of a text, of a life story, some of which you’ve written and told in past writing?

Wark: I’m kind of always open-minded about feedback about my own work. I’m also pretty controlling about the final product. So it’s nice to sort of give that over a little bit and to just trust Jessie in the creation of certain ventures. That was actually really kind of refreshing and liberating as well.

Rovinelli: At the same time, I gave McKenzie sort of a prompt. I gave her the themes that I was interested in for the text, and then I edited the text, made some notes. But I kind of knew that whatever she gave me, I would include, more or less.

Filmmaker: Was there a plan for which sequences of her body would accompany which portions of the text?

Rovinelli: There was a trajectory that we stuck very close to, and she knew that. They should diverge. I’m really about processes that exist alongside each other that will then interact in this aleatory fashion. They just do. And then you tie them, you make sure that it works. I don’t like to do things totally at random, but I let things fall where they are and then tie up the pieces.

Filmmaker: At one point in the film, McKenzie uses the words “the sleight-of-hand of cinema.” Is there something to that effect that makes cinema unique in how we tell life stories?

Rovinelli: I mean, all of my films have been about the way in which an image is not truth. Or at least that an image is constructed. I hate talking too much about transness, you know, [but] we are looking very closely at the trans body. And so it’s like, the body creates an image, right? And then that image is received and the image is, in some ways, the reality. But the image is a marker of a shift. So, there are always these multiple inflection points that happen between McKenzie’s body making it to us. This has happened and changed over the course of her life and in the time I’ve known her. And then in the course of putting orange light on her, in the course of framing her in these ways, the image is extremely contingent. So, I think saying “the image is not truth” is perhaps untrue. I think what’s more interesting is that the contingency of the image is its truth.

Wark: Because the color oscillates. And, so, it’s like, oh, which of these is the real and which one’s not? You get a film that’s already altering your perception of what these things are. There’s some aphoristic activision. I’m interested in the mediating players in lighting, iconography. Not to spend too long on, you know, critique-of-the-medium thing, but to just sort of play around the edges.

Rovinelli: You are, indeed, iconic.

Wark: I wanted to be documented, too.

Rovinelli: That was the genesis of the film, was Mackenzie saying, “I will never be more beautiful than I am now,” which is I think perhaps the most poignant and touching phrase a woman can say.

Wark: Aging in general is just not a thing that gets talked about — certainly aging for trans people is not even a topic. But all of the trans people we know and love in our community, I hope, are going to live long lives, you know? So, what are those long lives going be like now that we, hopefully, get to have them?

Rovinelli: One thing that is so exciting about McKenzie: she carries this enormous image of work and life. And as she noted, we don’t often get to experience that. It can be quite rare for women like us. But it feels great that I get to make a film that continues to share that history and experience. But it’s also reciprocal, right? I don’t look to McKenzie as a woman with all the answers. I look to McKenzie as a woman that I’m very grateful to be around. Who does have quite a bit to teach me.

Wark: Teaching is not about knowing things, it’s just about knowing how to teach things. That’s it. So it’s a little bit of pedagogy going on, in terms of you account for how to think retrospectively about one’s life. It’s not a bad thing to figure out. Trans people tend to think forward a lot, and we have a problem with our past. How do you put it together as a story? And have agency about that?

Rovinelli: It’s not a bad thing, to have a past. It’s inevitable. It’s ceaseless.

Wark: Yeah.

[McKenzie says goodbye and turns her camera off but leaves her audio playing. After a few seconds of this, we manually remove her from the meeting.]

Rovinelli: We could have spied on her.

Filmmaker: Spying seems a little out of mood with the movie?

Rovinelli: I don’t know, there’s a little voyeurism there.

Filmmaker: Actually, while we’re talking about spying: how do you think life-telling—by others or by the life’s author—interacts with issues of privacy and disclosure?

Rovinelli: I used to think of my films as voyeuristic. Maybe that was sort of me pushing back against the idea that if you saw a naked body, it was intimate, you know, that it couldn’t also be voyeuristic. But I think maybe that’s just a combative tendency in me. I’ve really struggled with the idea of privacy. I always oscillate between being very open and then with the facade of joking, of style, of deflection. I think that’s a very important part of life as a woman and life as an artist. So it becomes this back and forth. Like, how does one encourage openness, vulnerability, and intimacy while understanding there is always a part that is kept back?

You see a lot of McKenzie’s body, and you hear a lot about her past in the film. But at the same time, she has a certain discretion. There are things that she won’t talk about. There are ways in which something is always out of frame. I don’t have an answer for this yet, but I have been thinking a lot about how one exists—and tries to exist—as a public body. I don’t believe in the idea that we should all be private. I think that that contains its own evasiveness. How does one exist fully in public, while maintaining a part, an element of privacy? And I don’t have an answer, but I think that there is this shuffling back and forth. Maybe you see that in the film, in this flickering, in this back and forth.

Filmmaker: There’s a moment where it feels like the film is ending, but then we get the tea sequence. And it’s a moment where things are obscured in ways they haven’t been, so far.

Rovinelli: Yeah, chopping off heads again. And yet, you see another person there, you know? That scene finally reveals her home life. We move beyond just her body into how her body exists in the world. But we don’t see outside. Like at the end, she moves outside, she goes fully in public, and we don’t follow.

Filmmaker: It’s tea in this scene, but it’s usually coffee. What is it about that ritual, for you?

Rovinelli: People are really noticing that, I’m going to have to stop. It’s been too much of a tic. I mean, I put it at the end here, usually it’s at the beginning. It’s a good way to get ready: the film takes place before the beginning, right? Like it might be a film about the past, but it takes place before the beginning. The film is an antecedent to whatever comes after she goes outside. There’s still a lot left. So maybe that’s why it comes at the end. Or maybe I’m just fucking around. But I like it. It’s a ritual of preparing. And characters are always preparing. They’re always fixing. Coffee gets you moving. It starts things.

Filmmaker: That scene rolls right into the credits, which really feel like they’re part of the film proper: McKenzie’s still speaking. How do the credits feel to you?

Rovinelli: It’s text, right? It’s a very text-heavy movie, and so the credits should be part of the text. It becomes impossibly dense I mean, something that I’ve used, again, in other films that I think I’m also fucking around with in a bit of a different way here is when there’s too much, when you can’t follow everything. There’s a lot in her text and it’s very dense and outside of the published printed form, I’m not sure you’ll be able to follow all of it. It’ll be really fun when there’s subtitles and there’s more words in the bottom and all that. But I think this density is really important because it allows for those moments of real vulnerability to kind of punctuate and really hit when they come out of this miasma of words. I think that there’s also something really beautiful in trying to follow something and being invested in the act of following and realizing that you can’t. It exceeds us. And then of course, there’s moments of the film that are much, much less dense, where you can actually just be present.