Back to selection

Back to selection

“Punching Above My Weight”: Director Simon Hacker on Partnering with NBA Star Gordon Hayward and Self-Distributing His Indie Comedy, Notice to Quit

I first met Simon Hacker more than a decade ago when I was teaching at the School of Visual Arts in New York and Simon was a film student. He stuck out as someone who responded to what most people around him in the classroom weren’t much interested in: tradition. While the nascent auteurists were looking to reinvent the wheel, Simon grabbed hold of the ideas of a couple of people I introduced him to: Alexander Mackendrick and David Mamet. I was preaching the basics of classical narrative storytelling, and Simon took the time to listen. “What happens next?” became his mantra. He sent me short scripts, which we discussed, and after his graduation we talked regularly about a feature script he was writing. That script has now been filmed, produced through the new production company Whiskey Creek, which Simon and former NBA star Gordon Hayward founded, and will be released – self-distributed, no less – as Notice to Quit on hundreds of screens on September 27.

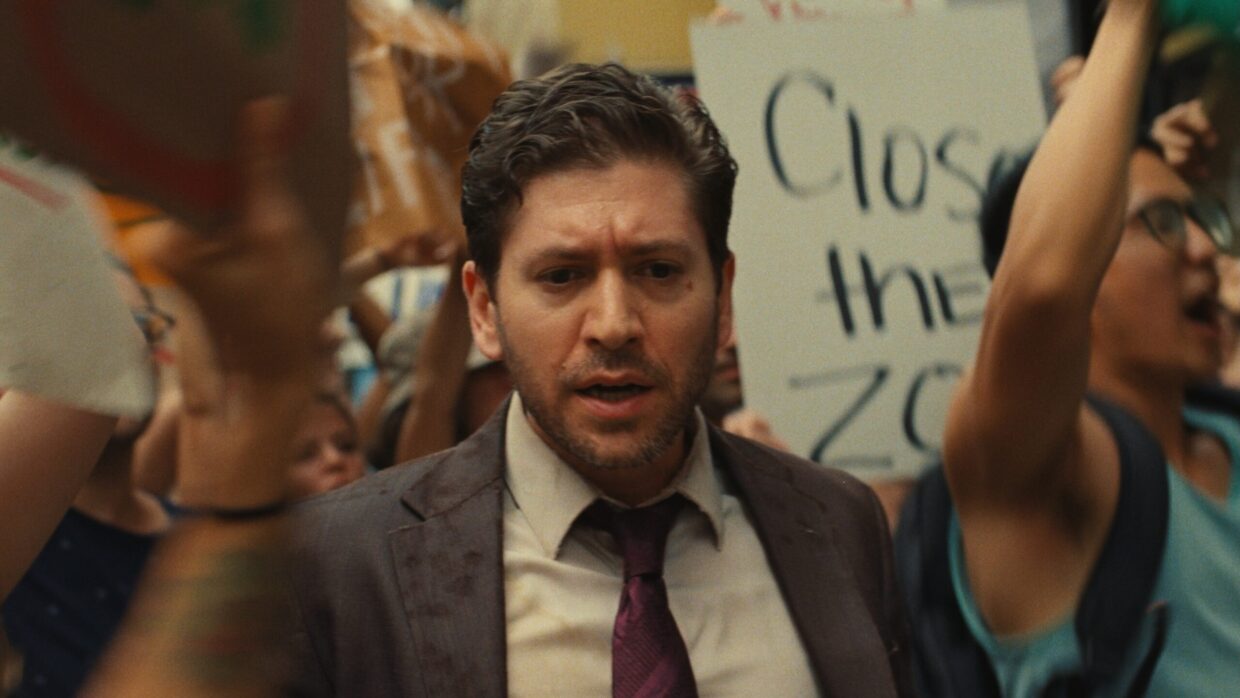

In Notice to Quit, Andy Singer (Michael Zegen), a scurrilous New York realtor and wannabe actor, trapped in the ceaseless hustle of urban life, does everything he can to rent fleapits to the unsuspecting while working a side trade in ripped off air conditioning units. Not surprisingly, it isn’t going well, which is why he is evicted from his own apartment the very day his daughter, Anna (Kasey Bella Suarez), shows up, upset that her mother/Andy’s ex has decided to move them to Florida. Set on a single miserably humid day, Notice to Quit is frenetic and funny, born out of a long pedigree of father/daughter stories. Hacker’s most potent dramatic reference is a film he reminds me I showed him in class: Peter Bodganovich’s Paper Moon (on more than one occasion Anna steps in to save the day when her father is clearly out of his depth). Hacker’s story also recalls Wim Wenders’ Alice in the Cities and Luc Besson’s Léon: The Professional, while Mamet’s Glengarry Glen Ross also clearly hangs over the proceedings. Hacker cites Llewyn Davis, trapped in his endless pursuit of recognition, and Punch-Drunk Love’s emotionally frustrated Barry Egan, as influential representations of the perpetually harried hero.

The story and characters of Notice to Quit find their roots in the brokers Hacker encountered moving from one New York apartment to another nearly a dozen times in as many years. He describes them as “charlatans” with such pride and belief in what they were doing, a contradiction of character that became the creative wellspring for Andy. But beyond that tangible reality lies a deeper resonance: the universal struggle of a man grappling with the weight of expectations placed upon him by family and peers, all while confronting the cold indifference of the universe. Zegen gives a wonderfully lively performance as Andy, trying to keep his dignity intact. Not a terribly likeable guy, at times abrasive and not particularly nice to his daughter, over the course of a day we do at least see the possibility of redemption.

As far as his large-scale distribution plan is concerned, Hacker insists that it’s the result of little more than being disciplined and organized, and what he calls “Herzogian perseverance” – endless phone calls, emails and spreadsheets, and an ability to ignore rejection. Plus a conscious decision at a certain point to remove his writer/director hat and replace it with one marked producer/distributor. Will his tireless efforts pay off?

Filmmaker: What I find interesting is that most of the film students I spoke to when teaching tried to get summer work on film sets as a production assistant. But not you.

Hacker: I was coming from such a faraway place – South Florida, Boca Raton. I had zero contracts in the film industry. When I came to SVA as a transfer from the University of Florida, I was burning with anxiety and an innate desire to get on with telling stories and become a filmmaker. I envisioned some kind of roadmap that I needed to create for myself, which from the start included learning how to make films but also, in parallel, how to make sure people would see them. I figured that any approach that took in one without the other wasn’t going to be very useful for me.

I knew enough after my first year at SVA about how things more or less worked in the independent space. I understood this to mean: you raise money, you make a movie, you bring it to a festival, you get acquired, you get distributed. But I wanted to know much more. I needed the details. That’s when I noticed that a major distribution company was advertising for a summer acquisitions intern. I was pretty persistent and bulldozered my way in there, and for a few months my job was to watch unsolicited submissions. It was a real learning experience.

Filmmaker: And you learned what?

Hacker: What it takes to get picked up by a distribution company, what components are needed to have a successful release of a film but also what the constraints are: the lack of a celebrity cast, a budget that’s too small, no immediately obvious marketing or positioning angles – that kind of thing. I learned what the films on the slush pile lacked, what was preventing them from being picked up. One day we all went into a screening room and watched a film that the company chose not to distribute but that ended up winning the Oscar. With no recognizable names in the cast and in a foreign language, they were sure they couldn’t package it and sell it to the public. It was a beautiful, poetic film, but from a business perspective it wasn’t checking enough boxes. That was a real eye-opener.

I came to realize what kind of films I wanted to make. They weren’t going to be low-budget Blair Witch horror flicks or daring, auteurist pieces made for $50,000 in my mother’s basement, like Pi. As much as I love Fellini, it was populist David Lean epics that I really wanted to make – coherent stories with a beginning, middle and end, in that order. I also began to understand how the film industry operated and how predatory the business could be. I learned that the independent model of film was packed with middlemen. I learned about distributors who bundle their sales together and cross-collateralize releases. I also realized that I could tailor my own bespoke release strategy, work on it around the clock with my team, and invest myself in ways a large distributor might need additional resources to obtain.

I did the internship and got to know everyone there, after which I figured that when I graduated SVA a few years later and made my first movie, all I had to do was send the people I had worked with the film, and they would buy it. That was my immature, larger than life, 20-year-old mindset.

Filmmaker: How did you come to work with the Safdie Brothers?

Hacker: Towards the end of my time at SVA, I printed out a resume, went over to the Safdie office, waited outside until the FedEx guy went in, and slipped in behind him. I went upstairs but the brothers weren’t there, so I handed my resume to someone. The next day I started following up by email until Josh eventually responded. The minute I had his attention, I didn’t stop barraging him. My emails had “I WILL WORK FOR FREE” as a subject line. Josh and Benny had just made Heaven Knows What, which was doing the festivals. I saw a trailer for the film and was overwhelmed. Absolutely overwhelmed. I knew I wanted to work with these guys. I think I knew their names because you had mentioned The Pleasure of Being Robbed and Daddy Longlegs in class. They were doing what I wanted to do, and they clearly had a voice. They were getting it done. As I got to know them and how they made their films, they became even more inspiring. The way Josh made The Pleasure of Being Robbed, for example. He convinced Andy Spade to hire him to make a commercial for Kate’s handbags, and with Benny they turned it into a feature film. The Safdies clearly knew how to get things done. If nothing else, they had figured out how to get people’s attention. Very quickly they built their brand and audiences bought in.

Filmmaker: And you went to work for them.

Hacker: Heaven Knows What was in post, and it was clear that they were moving up in the film world very rapidly. I grabbed hold, and they pulled me into that pressure cooker. I was fresh out of film school – 22, 23 years old – learning how tough I would need to be if I wanted to make films. I saw the endless hours of hard work that Josh and Benny put in. Theybabsolutely would not quit. It was inspiring and it changed the way I viewed everything.

Josh gave me the opportunity to make a making-of doc to go onto the Blu-ray and DVD release of Heaven Knows What. He and Benny helped me a lot with the editing of that film, which was the first time I had worked on something with real deadlines. I’m out of school for a month at this point, but I still had a very student mindset. I had much too much footage and was trying to impose meaning on things that didn’t have much meaning. I remember Benny telling me over and over again, “You can’t bore the audience.” I spent a frantic two weeks re-editing it based on their notes. They opened my eyes to how and why what in my edit was good, and what wasn’t.

Filmmaker: How long were you working for the Safdies?

Hacker: About two years. I left when Good Time was in post. They were great years, but I was ready to move on to the next thing. They were busy with development on Uncut Gems and figuring out how to acclimate themselves to a new tier of filmmaking and building relationships with a different set of collaborators. The whole thing was an amazing experience for me. It was unfettered access to these guys at an incredible point in their careers – in the room when they were having endless creative conversations. But I hit a ceiling. I had to stick to the roadmap in my mind. From Josh and Benny, I had learned so much about how to make a movie scrappily in New York City for no money, and perhaps most importantly, I met so many incredible people when I was working with them. The producer of Notice to Quit, Wyatt McBride, was a PA on Good Time. My production designer Stephen Phelps on Notice to Quit was the prop master on Good Time. Brendan McHugh, who became my mentor, was the co-producer. It was through the Safdies that I began building my own network.

Filmmaker: How did you secure financing for Notice to Quit?

Hacker: Through Whiskey Creek, the production company I founded with Gordon Hayward, an NBA All-Star.

Filmmaker: How did that happen?

Hacker: I was hustling around town trying to get any kind of corporate industrial job to pay the bills. At this point my only professional credit was the Heaven Knows What making-of. I had a friend who worked in marketing, and through him I picked up some small commercial jobs. He gave me a call when he began working at a sports media company called The Players’ Tribune, and said they were looking for someone to make documentaries.

I got my foot in that door, but immediately knew it wasn’t the right place for me. There were very talented people there, but I couldn’t really stretch my wings, so I pulled one of the VPs aside and said, “Thanks for this opportunity, but I just don’t think I’m the right fit here.” I realized that I would rather hustle around town and be my own boss, and instead of shaking my hand and sending me on my way, this guy says, “OK, well… what do you want to do?” I told him I wanted to make movies – features, or even documentaries. I want to be a storyteller. He says, “Funnily, enough, this NBA player just broke his foot in half. His agent contacted us. They want to make a long-form feature documentary that charts his rehab process. It could be a year-long process. You want to lead that up for us?” That was immediately interesting to me. It wasn’t going to be a two or three-minute commercial spot that would run on social media platforms. It could be an opportunity for my work to be seen by a large audience.

I filmed for months with him, in meetings with doctors and trainers. I really got to know him. He and I shared many hours together. He struck me as highly intelligent, challenging and curious, as well as a bit of cinephile. He was spending hours on the road watching films. In the end, the documentary series – the story of a guy trying to heal and get back to playing the game he loves – was successful and sold to The Athletic.

Then I got a job as a field producer on the first season of the HBO show How To with John Wilson,and used some of the money I made to rent a tiny office in Chinatown. I signed the lease in early March 2020, days before the Covid shutdown. Like everyone else, I was struggling to find work, until Gordon got in touch and asked if I would edit some material for him. He’s a pretty serious esports player, and needed help with a video stream that he wanted to put onto YouTube. We had spoken so much about films during our time together, so I asked Gordon if he would want to start a production company. He liked the idea, and suggested we focus on esports. I wrote up a bunch of concepts that we could pitch to networks and YouTube. Basically: there are lots of professional esports players, some of whom have really interesting stories to tell, who need exposure.

Filmmaker: When did you pitch him the idea of making Notice to Quit?

Hacker: For months I tried very hard to get something going in esports as I knew it was important to Gordon, but I couldn’t get anybody to bite. At one point Gordon called me and asked what other ideas I had. He knew that my ultimate ambition was to make movies, and when I told him I had a script for a feature film I wanted to make, he said he wanted to get behind it. He was immediately excited by the idea of producing feature films, and wanted to be involved throughout the process as much as he could. It was challenging for him as he was still in the middle of the NBA season, but he was an incredible partner, helping to open doors and make calls whenever he could.

In the middle of the pandemic, I cold-called and then sent my script and the 40-page look-book I had made to the casting director Avy Kaufman. She liked the script and turned it over to her son, Harrison Nesbit and his colleague Scott Anderson, who she worked with. Avy wouldn’t be working directly on the film, but it could be cast using her name which would open doors for us at the agencies. So they put together a wishlist of big-name actors, which included Michael Zegen. I took that list, along with the script and a budget, plus the look-book, and flew down to North Carolina to meet Gordon at his home. He was excited by my pitch, but it still took me three hours to work up the courage to ask him if he would consider coming on board to help make the film. As I’m walking out the door, he said yes to me.

Filmmaker: You had a full budget at that point?

Hacker: No. I hadn’t line produced a movie and didn’t know left from right. I basically figured how much I thought I could get from Gordon to make the movie and fit the budget into that number. Not a good idea, because in the end we needed much more.

When the script was done, I did everything I could to get an established producer on board, some industry professional who had experience of movies of this size and scope. I sent the film to a hundred producers but I just couldn’t find the right partner. Most of them really liked the film. Maybe they saw the small budget as limiting in terms of what kind of return it could yield, because you can only do so much with a film this small – even though I think Notice to Quit plays like a $10 million movie. I realized that I was going to have to produce the film myself, which was a pretty insane task, especially for someone who had never produced a movie before. And a week later, Gordon and I are overseeing the formation of our company, Whiskey Creek.

Filmmaker: How long after Gordon came on board did you start shooting?

Hacker: I flew to North Carolina on March 2021. We were filming by late September. But don’t let that fool you. It was a very difficult process, starting with the realization of just how difficult it is to get an actor of note attached to a first-time director’s feature film. Why should they take a chance on you as an unknown entity? At one point I was going to play the part of Andy myself. I learned that the only way to make a movie is to put a date on the board and say, “That’s when we’re starting.” You can’t wait for every piece to fall into place. You have to learn how to build the boat while you’re already at sea. The most discouraging part of the process is the general rule that you can only offer one actor the role at a time, which means you have to wait for them to read your script, talk about it internally with their team, and decide about it. While that’s going on you can be making back-up plans, but you basically just have to sit and wait. And once it begins, it gets even more difficult, as you’re begging for favors from your underpaid crew and every vendor going. Like me, all my department heads were leveling up. This was their first feature. With Wyatt, who until this point was the only producer who believed in me, I slowly built out a team. Jordan Drake and Stephanie Roush came aboard, and together we plowed forward.

More money would have bought us more time and control. But we just didn’t have it. This is a story that takes place over a single day, and a lot of it takes place outdoors, so if it rained there wasn’t much we could shoot that day because we had no cover sets. And we were working with a 10-year-old whose hours were capped by labor laws. And COVID was still very much a presence. And we lost days because we thought we had locations locked but that fell through. And we didn’t have enough money to rent props, so we rented a truck and a storage unit and Stephen Phelps drove all over New York using Craigslist and other online marketplaces to grab as much free furniture as he could. The first and final days of each month were best, when people were moving out of their apartments.

And, of course, we’re shooting on film, which is slower than video, and we didn’t have the budget for real lights. And Mika Altskan, my DP, was brought onto the project only ten days before shooting began because the original DP had to drop out due to family issues. Given the circumstances, he did an extraordinary job and kept a coherent look across a year of shooting. There are almost no handheld shots, and dollies take time to set up. People who read the script noted how frantic the action was and asked if we were going to shoot handheld, but that was never my plan. So generally I thought we could move faster than we did. Of course, in some way, Andy, who is some kind of Sisyphean character, carrying the weight of the world on his shoulders, is a stand-in for the film director – for me.

Filmmaker: Did people advise you to stay away from film?

Hacker: Everybody said I was out of my mind. Mika was especially apprehensive for us to shoot on 35mm. The script was very ambitious, lots of locations, and we were on a tight timeline with a child actor. He tried to pitch me on 16mm, but eventually relented and came up with the idea of shooting exclusively on 35mm tungsten. I got great deals from ARRI for the camera package and support from Kodak. We only used 500T and 200T, which gave us more latitude for daytime exteriors. For a film that takes place over a hot summer’s day, we would have much more separation when warming the image, as the tungsten would keep the shadows cool. Our colorist, Mikey Rossiter, did the most amazing job when he took a year’s worth of footage, shot across different seasons, and made it feel like one single day.

In the end, we didn’t wrap until September 2022. I knew after principal that we didn’t have what we needed, which meant I was going to have to raise more money and then bring everybody back who just worked for nothing to get it done a second time. The reshoots were extremely organized because as soon as principal was done, I immediately knew what I was missing, so I was very tactical about not wasting a second when we went back for reshoots. We were very focused and targeted, going in just for her closeup here, his point of view there. To some degree I was fortunate to have that extra time because the learning curve really was so steep, and by the time we did the reshoots, I was much more equipped to do my job. There are some benefits to shooting a movie over the course of a year, even though, as usual, there were plenty of things beyond my control, like the fact that we had to work mostly on weekends because Michael was shooting the final seasons of The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel and Bella was at school, although at one point she got cast in an Adam Sandler movie and had to go to Canada for six weeks, so we had to wait until she got back. What might have been two weeks of reshoots became eight months.

Filmmaker: Maybe there were more conceptual reasons why you stayed away from handheld imagery.

Hacker: We shot on the streets of New York, and the film is obviously set in that town, but at the same time I wanted it to be a heightened reality. It’s a reality we recognize, but in an uncanny way. And I wanted to get some comedy in there, which happened when I cast Michael Covino. I happened to be working in the same office building as him in downtown Manhattan and just bumped into him in the elevator. This was on the heels of him winning the jury prize at Cannes for The Climb. He was actually instrumental in helping me get Michael Zegen attached. He knew it was an uphill battle for me, trying to get an actor of note to believe in a first-time director. He went to bat for me.

Filmmaker: What does the title mean?

Hacker: A “Notice to Quit” is the term when a landlord hands a tenant an eviction notice. You have 14 days to leave the premises. And so Andy is literally being evicted from his apartment – which is the inciting incident of our story – but somehow, in a metaphorical way, he’s being evicted from his daughter’s life.

Filmmaker: How was post-production?

Hacker: My editor, Gilsub Choi, did an incredible job of helping me track beats and shots across the extended pickup/reshoot period. When we had a strong rough cut, I wrote a letter and pleaded with Christopher Scarabosio, who has mixed for Paul Thomas Anderson, Wes Anderson and Noah Baumbauch, to work on the film. We worked for a week together. He did amazing work, blending in all the reshoot material into the principal. He really made it sing. Everything he touched, he elevated. When it came to music, as usual, I was punching above my weight and asked Alexandre Desplat, who responded very positively to the film but didn’t have time for the job. The guy who ended up composing the score is a brilliant young Italian multi-instrumentalist called Giosuè Greco. I sat in the garage of his small East LA home as he single-handedly played more than a dozen instruments while we watched the film together. He basically composed the whole movie with me sitting behind him. We also got some music from Jack Antonoff. Oscar Boyson, who was one of the producers of Good Time, had directed a music video for Jack, so I edited together a shot from the film – Michael running down 72nd Street through the pigeons – with some of Jack’s music. Oscar put me in touch with Jack, and he loved it. He sent me his stems from a Bleachers album and we worked them into the mix.

Before we finished the edit, I had gotten a major talent agency on board as our sales rep. They were going to handle distribution and help us get into festivals. We got into six or seven regional festivals, but they wanted me to hold out for something better. They thought that a small festival premiere would somehow lower the value of the film and hurt sales. I listened to that advice for almost a year, waiting for something bigger to come along.

Filmmaker: At what point did you decide that another strategy was necessary?

Hacker: The film was just sitting on the shelf. We had to do something with it – not just try to get it into festivals and hope it would get picked up. We had gotten into some regional festivals, but no “premiere” or “international” showcases. I was continually being told that I needed to wait for something bigger, as that would help get the film sold or bring a distributor onboard. But I didn’t want to wait, so just like I produced the film myself, I set about distributing it myself. Knowing what I knew about films that had been self-released, I began to study and find case studies of movies that had basically been self-distributed by the filmmakers, either in theaters or streaming. For me, streaming was never our first option. That was never what I wanted. We shot on 35mm, after all. I’m a fan of classic cinema. There’s no better way to watch a movie than in a cold, big, dark black room. We shot this for the big screen and we mixed it for the big screen at Skywalker.

I looked into contacting theater bookers, but at the same time I had a sense that getting the film onto screens might be something I could do largely myself. I began scouring the Internet, working hard to find the right person at the right organization, then sending them the film. It took me a couple months to break through that wall, especially because I went for the big names first – AMC, Regal. I had to get their attention and convince them to put my film in their multiplex next to Beetlejuice Beetlejuice. My strategy developed day by day as I learned more about releasing and distribution, including, for example, just how competitive the independent circuits are. Those theaters generally play only the best and the “biggest” indie movies – the big festival winners from A24 of Neon, films with a recognizable cast, that kind of thing. There were lots of lessons to learn.

I got an excellent trailer cut and after weeks of making calls and emailing, got it in front of the right people. They liked what they saw, so we sent them the whole film. And some of them said, “Sure, we’ll take a chance on playing this on some of our screens. But we want the lion’s share of the revenue.” I didn’t care about that. I just wanted to be in these places. So we cut these deals that basically favored the theater but gave us real estate of all these screens. And we didn’t have to put up any money upfront.

Filmmaker: But you have to pay for advertising, posters, DCPs – that kind of thing.

Hacker: Yes, there are costs for marketing and PR efforts, as well as delivery. We’ve been flooding Instagram and YouTube, those kinds of channels, with some very targeted digital marketing. It’s a multi-layered, completely digital strategy we’re rolling out across numerous platforms. We’re already scheduled to open on 250 screens, but it’s very likely that number will grow substantially between now and the release date. It sometimes isn’t until the Monday before the Friday release of a film, once the buyers at the different circuits see what kind of pre-sales and marketing and publicity you have going, and how films they are playing performed over the weekend, that the final decisions are made. If the film performs and they find the run space, we can expect to expand into even more screens, but we may play “split,” which means you get two showtimes a day instead of a “clean” run of five showtimes a day. If after a week the theaters want to pull the film, they can. I’m not guaranteed more than seven days. They have all the power. It’s important that we hit a certain number of ticket sales, and that number varies based on the location. For example, the Regal at Union Square in New York – we’ve got to sell a few thousand dollars of tickets from Friday to Sunday. But in Missouri, we might only have to sell a few hundred dollars of tickets. If we hit those numbers, we’ll hold it for another week.

Filmmaker: What’s so unique about what you’re doing?

Hacker: We’re a team of first-time filmmakers who, on an extremely condensed timeline and with very limited resources, cut deals with the big box exhibitors around the country and are going to show our 35mm film across hundreds of screens nationwide. We didn’t have to pay for the screens, we didn’t four-wall. I was the booker. I made hundreds of calls and sent thousands of emails to get in front of the right people. I didn’t hire someone to do the work for me. I think that effort earned me points with buyers across different circuits. And now we’re being treated as a proper distributor, meaning we’re going to take a percentage of the box office. Even more exciting, the backend is being shared. Every department head is a partner in the movie, meaning that if it does well, they do well. It’s not just the actors and producers. My production designer, my assistant director, my costumer, gaffer, my sound mixer, DP – they will all make money. A true team effort.

Filmmaker: What’s next for you?

Hacker: We’re injecting capital into the company to expand upon the blueprint and foundation that I’ve laid so we can scale up these kinds of distribution efforts and help bring overlooked independent films to the marketplace. Once word of our distribution company got out, the emails flooded in – a combination of look-books, scripts and screeners. And I’m working on a new script, which is nearly done. Coming from such a conventional place, friends and family always told me to find something to fall back on. They thought being a filmmaker was a pipe dream. At every step and stop along my roadmap, whether it was an editing gig, a commercial, whatever, the opportunity to take a turn presented itself. Should I move forward along the path of uncertainty or shore myself up by giving myself a backup. There have been many temptations – a steady paycheck, a more convenient lifestyle – along the path. But as David Mamet says, “Those with ‘something to fall back on’ invariably fall back on it.” I’m out there, trying to make the next film. It might be easier to make, it might be more difficult… I don’t know yet. But it will happen.