Back to selection

Back to selection

“What is Remembered… Is a Political Act that Can Be Weaponized”: Vicky Du on Light of the Setting Sun

Light of the Setting Son

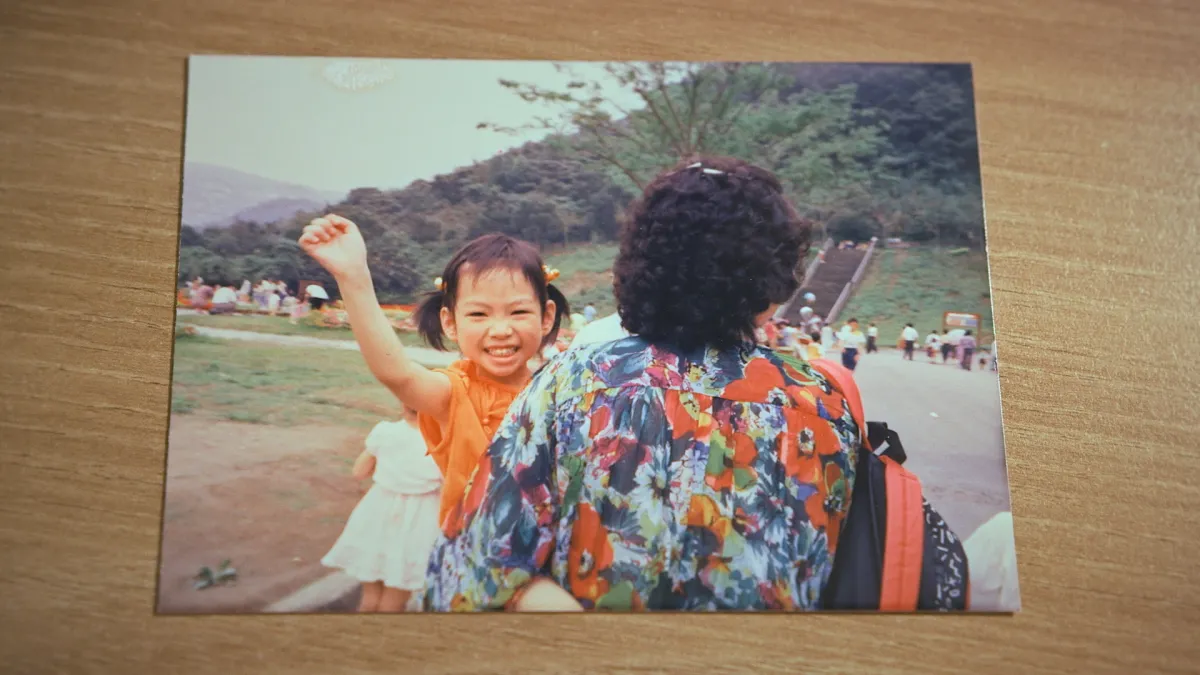

Light of the Setting Son Vicky Du’s Light of the Setting Sun is both intimate and expansive, tragic and hopeful. It’s a globetrotting look at the filmmaker’s own family across three generations and a trio of countries: the U.S., where Du grew up; Taiwan, where her parents hail from and where many of her relatives still reside; and China, where 95 percent of the clan was massacred during the Cultural Revolution. It’s also a delicate unearthing, and a piecing together of personal history through archival footage and interviews with family members – some more reluctant than others to address the inherited trauma forever looming like an unacknowledged shadow. That is until Du uses her camera to coax it into the light.

A week prior to the April 18th DCTV premiere of Light of the Setting Sun, Filmmaker reached out to the queer, Taiwanese-American director, whose eclectic CV includes several years as a worker-owner of Meerkat Media and a BA in Biological Anthropology from Columbia.

Filmmaker: I know this doc originated after the revelation of your brother’s mental breakdown, which led to family therapy sessions and the subsequent revelation of an inherited trauma your parents never spoke about. So was your everyone always onboard with participating, and did you plan to include your immediate family from the start? Did the film change from its initial conception?

Du: Initially I had planned to do an observational film that followed 10 characters from the Chinese diaspora, including my grandfather – a retired pilot who fought for the Kuomintang and against the Chinese Communist Party. I wanted to understand how the unprocessed trauma of the Chinese Communist Revolution of 1949 and the subsequent Cultural Revolution continued to affect all of us.

However, the path of the film changed after my mom, dad, brother and I did a genealogical tree exercise during family therapy. I saw that trauma had affected nearly all of us – my grandparents, aunts, uncles, cousins, and my immediate family – in China, Taiwan, the US and Canada. I was so compelled by this because the effects of the war felt inescapable, despite time and place. At that moment, I realized my family should be the characters in the film, that they represented what I was trying to capture.

I started filming with my extended family first, because it was emotionally easier. Some family members really enjoyed speaking with me; for others it was much harder, or they chose not to participate. Eventually I knew I had to film with my mom, dad, and brother as well. They were onboard from the moment I asked them.

Filmmaker: I’m also quite curious to hear how your background in biological anthropology might have influenced your approach to the film, and to filmmaking in general.

Du: In particular, I studied primate behavioral ecology, where I would spend many days watching wild monkeys and noting certain behaviors.

The work was very observational, patient and curious, and I probably approach filmmaking the same way. My tendency is to set up the camera, pose the question or conversation and roll. I like to give room and space for things to happen naturally, and I just watch. Sometimes nothing happens, and sometimes the conversation moves to a place beyond what I know to ask. I don’t know what’s the signal from the noise yet at that point, so I like to collect and watch it all.

Filmmaker: I likewise found it quite interesting that you’re partly based in Berlin, in a country where intergenerational trauma passed down from Nazi perpetrators (as well as the Stasi – and its victims) is openly acknowledged, perhaps even capitalized on with the dark tourism industry. So how did living there influence the film, or your thoughts on how different cultures deal with this delicate topic?

Du: I’m fascinated by the similarities – everyone here is just one or two generations removed from war (if not directly impacted by it). There are bullet holes in buildings, remnants of the Wall, and war memorials everywhere. My partner’s parents said the city used to be all rubble. That was the first thing I noticed — people in Berlin intuitively knew what the film was about. It wasn’t just about China or Taiwan. They could relate the dynamics to their own family histories.

One difference, though, is that the German government openly addresses its past and aims to foster a culture of remembrance by recognizing and memorializing the violence of the War, the Holocaust, and the GDR. I used to think this was in direct opposition to China, where it is illegal to even mention the Tiananmen Square massacre, let alone the millions who starved during the Great Leap Forward.

However, now we have seen that reckoning with unprocessed grief and trauma is so much more complex than any public acknowledgement or apology; and that what is remembered, and how it’s remembered, is in fact a political act that can be weaponized as well.

Filmmaker: The film world-premiered at Full Frame last year, had its international debut at EBS International Documentary Festival, and went on to Euro-premiere at IDFA. I’m curious how these various American, Asian and European audiences responded. Were there more similarities than differences?

Du: It was a goal of mine to screen the film on three continents, which would suggest that even though the film is a very specific story about a Taiwanese-American family in New Jersey, the themes and experiences of being a part of the post-war diaspora are universal. That the tone and dynamic of my family is actually quite common, even if it’s not often depicted.

Post-WWII European and Jewish diaspora audiences felt a kinship with my family, as did Korean audiences with family abroad who also experienced trauma from the Korean War. Young and queer Asian diaspora audiences had very visceral and emotional responses as well, which really touched me.

Filmmaker: Finally, how do all your family members feel about the film? Have the reactions been mixed?

Du: My family was always supportive of the film and believed in its importance; but at the same time, I do think it’s hard enough to share these vulnerable moments on camera, let alone with an audience. It was hard for my brother to see that one of the most difficult periods of his life was the crux of this film. My mom similarly had a complicated reaction, and of course she was worried about how my brother would feel. Ultimately, I gave my family veto power over anything they felt was too personal or impactful in their lives.

My entire family was incredibly proud when the film won the Grand Jury Award at the San Diego Asian Film Festival – especially since the news was published in World Journal, the largest Chinese-language newspaper in the United States. And they’re very excited that the film will screen in a cinema in New York. Coming from a small island, this gives them a lot of pride as Taiwanese people – recognition that their stories are artful and important, that they matter to other people.