Back to selection

Back to selection

“At the Same Time that We’re Fighting for our Lives, We Are Also Agents of Exploitation, of Domination, of Violence”: Pedro Pinho on his Cannes-Premiering I Only Rest In The Storm

I Only Rest in the Storm

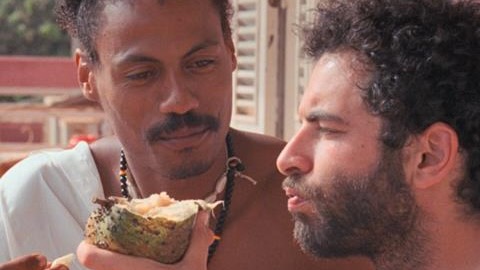

I Only Rest in the Storm Pedro Pinho’s Cannes-premiering I Only Rest In The Storm follows Sergio, a naive do-gooder who, as the film’s title implies, finds inner peace in places of chaos. In this case it’s the hurly-burly of Guinea-Bissau, where the Portuguese environmental engineer has been hired to produce an impact report that will pave the way for a road-building project to commence. There he meets two charismatic characters, party-loving besties Diara and Guillermhe, the former a native, the latter a Black Brazilian expat. And thus begins a bizarre triangle of love-hate attraction – fueled by a colonialist past, a capitalist present, and an uncertain future for them all.

Just prior to the film’s Un Certain Regard debut, Filmmaker reached out to the Portuguese director and cinematographer whose documentary projects (2008’s Bab Sebta, co-directed with Frederico Lobo, and 2014’s Cidades e as Trocas/ The Cities and the Exchanges, co-directed with Luísa Homem) likewise explored the heavy themes of capitalism and migration in today’s supposedly postcolonial world.

Filmmaker: So how did the idea for this film originate? Why set it in Guinea-Bissau?

Pinho: The idea for the film grew out of years of travel and lived experience in West Africa, especially in Mauritania and Guinea-Bissau. I first went for professional reasons, but what followed were deep relationships and a recurring need to return — driven by a desire to look at Europe from the outside, to gain distance from the structures that shape my own life.

On one of those trips I visited Bissau almost by chance. What I encountered there was profoundly striking — a reality deeply different from the idea widely spread in Europe. A diversity of cultures, languages, cosmogonies, all united in a country designed firstly by colonial rule, but a lot by the liberation struggle and the years that followed independence. The marks of resistance to invasions throughout the centuries is still very present and alive there. And that made me fall in love with this territory, and fall in love with the part I am still discovering of some of those cultures.

It was also the first time I directly witnessed the world of international cooperation — NGOs, “expats,” volunteers, foreign aid workers — a space that raised unsettling questions about power, complicity and historical continuity of colonial relationships. The film was born on that ground. Not from a wish to “represent” Guinea-Bissau, but from an experience — a collision, really — with a moment that revealed how old colonial dynamics persist in new forms. That encounter stayed with me. It kept growing, questioning, resurfacing — until it returned, years later, as fiction.

Guinea-Bissau wasn’t chosen as a setting. It imposed itself — as a place where liberation struggle, history, power, and European presence could no longer be thought of separately.

Filmmaker: How did you go about casting? I’m especially curious about your trio of lead protagonists, whose chemistry is surprisingly strong.

Pinho: The casting was carried out over a work period that was proposed to various actors, and one of the things being considered during that time was the subjectivity of those actors. What kind of subjectivity could they, in some way, lend to the characters? Lend, not in the sense of transferring a particular worldview or a particular morality, but rather in the sense of seeing how those people, those actors, react to reality. The degree of adhesion or repulsion, of empathy or antipathy they might feel toward the other characters, and toward the elements of reality and of the narrative.

And that’s also how I realized that between Sérgio, Cléo and Jonathan there was a very strong relationship; not necessarily always one of attraction, but a very complex one, difficult to read, full of hesitation. That was one of the reasons that led me to believe it was a good choice. Of course, when I brought the three characters together in the same casting session it was absolutely explosive. But rather than being put off by that explosiveness, it seemed to me it could be reversed and transformed into energy for the film. I believe that, in some way, did happen.

Filmmaker: How did your documentary background influence your approach to the film?

Pinho: What interests me is that reality always stays ahead of the camera – the camera chases it, it never anticipates it.

Because the moment you set up a tripod, a camera, and ask reality to happen — once the technical setup is ready — we’re already speaking about something else; about a different kind of distance, a certain readiness. That tension between life unfolding and the camera pursuing it is something that fascinates me — and which I also find very beautiful to film in fiction. How to produce that flow of life always unfolding, without interruption. With a rhythm of its own, independent of cinema’s needs.

And yet at the same time you’re managing certain technical logistics, a group of people who have to be synchronized in order to record a moment. You’re finding strategies so that this flow isn’t interrupted — the natural flow of life, in which we can’t foresee what will happen in the next second. Those strategies are, I believe, what gives me the greatest pleasure in making cinema.

Understanding how to constantly shuffle things around, so that we are all in a state of permanent improvisation, in constant reaction to stimuli. As if my job as a director were to create that confusion, that chaos, so that everyone is wide awake and listening, waiting for the right moment to capture a sound, an image, a look, a line, a dialogue from the other. That is the most exciting and most marvelous thing I find in cinema.

Filmmaker: So were all the film’s scenes staged – or were you allowed to shoot actual ceremonies and the daily work of the country’s inhabitants?

Pinho: All the scenes were created, the situations all generated by us. But the aim was that within those situations proposed by the narrative people would act as if they were in life; without fiction imposing itself too much, and without the technique interrupting too often, breaking the flow.

Of course, the ceremonies and the work were often provoked — more the ceremonies than the work — but provoked in the sense that they repeat a series of gestures that have already happened or usually happen, and which function almost automatically, without the need for instruction. Without having to say: “Do it like this here,” “turn that way,” “go that way because the camera’s over here.” We tried to make that mise-en-scène time — the action-cut time — disappear as much as possible so that we could respect the events, the situations, the occurrences happening in front of the camera.

In one particular scene — when a delegation from an NGO comes to assess the implementation of a latrine program in a village — I’d actually observed that 15 years earlier when I was trying to make a documentary about NGOs. I’d only filmed for one day when I saw that and lost the will to make the doc. It was too strange and violent to witness. It struck me in very strong and bizarre ways; and made me incapable not just of holding a camera, but of even remaining there.

I felt such a profound shame — all the more so with a camera in hand. So I decided to return to that village where it had happened and ask the people if they could recreate the situation. To do so as a kind of exorcism — to purge that diffuse but strange and humiliating memory I had. And not only for me.

So after a long period of conversations and negotiations, the inhabitants of the village agreed and took part in the game. And I feel — I think that comes through in the film, maybe even more in the off-camera moments, in what’s not edited in, or in what’s said but not translated — that the people are playing with me, playing with us, with the proposal we made to them. They entered into a game. Maybe, in my naivety, I believed fiction could serve as a kind of revenge.

And that was quite interesting, though difficult, to propose and to perceive how that reenactment could happen in the form of a game; one that could compel a digestion and re-signification.

Filmmaker: The film struck me as a bit of a tightrope walk in that we see Guinea Bissau through Sergio’s often rose-colored – i.e., exoticizing – eyes. So how did you avoid the “poverty porn” trap with a main character who can’t help but romanticize?

Pinho: The way I see that idea of poverty has nothing to do with a condition, nothing to do with some immanent state of a given person, a given population, a given territory, or geography.

To me, the idea of poverty only exists in relation, in comparison, and in struggle. I see it as a relationship of imbalance of power. The way I understand that word — which is a word I even try to avoid — has to do with struggle, with relationship. That is how I understand the word “poverty.” Not as a condition, not as a fatality, not as something inherent, not as immanence. It has nothing to do with that.

And I think that’s part of the problem with the European gaze, or the Western gaze. This considering that outside our place of privilege there are a series of conditions that are just there, like that, by chance, because history played out as it did. That’s not how I see it. What happened in history — and continues to happen in the present — is that there’s a set of opposing forces, a set of people, of lives, of aims, of lines, of impulses, that are in struggle.

Some forces are fighting for life; others for exploitation, for profit, for the maintenance of privilege, for hegemony — cultural, technological, scientific, artistic, aesthetic, moral, political, and so on. Wealth or poverty, in their many degrees, are that struggle between two fields, between two impulses. And they only exist in comparison, in confrontation. That is, of course, a simplification — a simplism I allow myself. There are simplisms I don’t allow myself, but this one I do, in an attempt to understand what it is and to integrate it into my way of looking.

That struggle happens against people who are fighting for their lives, for the lives of their children, for their day-to-day, for growth, for food, for water, for school, for healthcare, for all of that. People fighting to have time to rest. To not be crushed by the obligation of work, of money. Those people exist everywhere. That’s all of us. Those people exist in Portugal, in the United States, in France, in Guinea-Bissau, in Mauritania — everywhere.

And then there are other forces coming from above. That go to the villages in the north of Guinea-Bissau where we filmed to extract rare sands, to expel entire communities from their land, to pollute the waters, to exploit labor, and to extract resources for centuries, disrupting and perverting the balance that had been built over millennia. This happens everywhere. Yes, it happens in Guinea-Bissau, in Mauritania, but it also happens in the United States, in Portugal — in Covas do Barroso, for example, and in all the fracking territories of the US. But these relationships don’t imply any degree of fatality, no ontological coherence between the people living that struggle and their condition.

So I think the answer to your question is that the film does not avoid that struggle. The film tries precisely to film it. But it tries not to look from a place of condescension, of assigning an inherent condition to the people being filmed. The film does not believe in that. It believes we are shooting a struggle – and that we are all fighting for life, everywhere.

And I think that might disarm the issue. (I think, I don’t know. Perhaps not.) But it tries to disarm that problem.

Of course, that struggle for life is not always clear, not always heroic or rosy, not always clean and not always as good and virtuous as we’d like it to be. Often it’s dirty, cowardly, complicit. It participates in several degrees in the same systems of domination, of exploitation. All of us, to some extent, participate in those systems.

At the same time that we’re fighting for our lives, we are also agents of exploitation, of domination, of violence.

So the moment you stop thinking of people as inherently this or that, and start looking at the relation — between opposing forces, but also within ourselves, between fighting for life and undermining the life of our neighbor — you realize that struggle is never won.

From that moment on, I think it all gains a different kind of complexity.Though there is a part of that expression — “pornography” — that perhaps the film embraces. Not in terms of poverty, but of explicitness. The film seeks a certain pornography of the word, in the sense that it plunges into a kind of polyphony of contradictory voices, of perspectives that speak about one theme but point in different directions.

So yes, there is an explicitness. Perhaps “pornography” isn’t the exact word, but there is that explicitness in the search for words. In search of the words that say explicitly what they want to say with every letter.