Back to selection

Back to selection

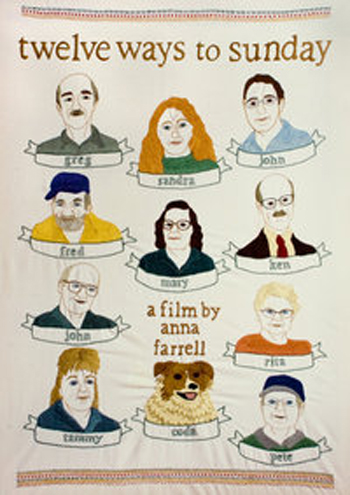

“TWELVE WAYS TO SUNDAY” COMES TO ROOFTOP FILMS

In this time of economic peril, many Americans have begun to shed frivolous spending for small but rich pleasures. With less nights of take-out or cineplex movies, they’ve learned that it’s the homemade things that count in this world. Filmmaker Anna Farrell portrays a tight-knit community in her documentary Twelve Ways to Sunday, one that always knew about the basic and organic things in life. Fixing up motorcycles, dishing up meals at the local diner, and canning fruit preserves, the people of Allegany County, New York, have always sustained through the good and bad times. Playing this Wednesday at Rooftop Films as part of their extended 2010 Summer Series in NYC (in part with IFP‘s Independent Film Week), Twelve Ways to Sunday shows that in the leanest years, people in rural America have always known how to persevere with strength and know-how, and that a different kind of wealth can be appreciated: self-sustainability, good conversation, rich stories, and getting to know your neighbors.

The beauty in Twelve Ways to Sunday is the unique and interesting cast that Farrell and co. have assembled for this film. A pastor who enjoys making peanut brittle that is hard and mixed with chocolate; Fred, a grizzled rough-talking old man who hangs out at the local diner and is friends with the co-owner, a hearty and witty young woman; an elderly couple who ride motorcycles and have tattoos, and a young woman who is an avid hunter, yet appreciates the beauty of the woods and its inhabitants.

Farrell had previously been a 2009 IFP Documentary Lab Fellow with Twelve Ways to Sunday, showcasing her film at last year’s Rooftop Films / IFP Lab Selections screening last year. She was co-director of the accompanying documentary with Opus Jazz: N.Y. Export, and has recently worked on both Tiny Furniture and Twilight.

I spoke with Farrell via email this month, in preparation for the screening.

Twelve Ways to Sunday features many memorable characters who instantly become endearing and interesting to an audience, and with a wide diversity. How did you develop the film project?

TWTS developed out of a desire to create a multi-character portrait piece about life in rural New York. My brother [Samuel Farrell, assistant producer] and I grew up in a relatively small town upstate, but I wanted to go further out in the state to find “our town” for the film. Allegany County stood out because of its poverty levels (one of the poorest in the state) and its deer harvesting statistics (one of the highest in the state). Self-reliance is one of the defining characteristics of all of my subjects. We basically started driving west and when we found this small town, Bolivar, NY, it really felt right, and people seemed willing to give us a chance. We ended up filming in a few adjacent small towns: Bolivar, Richburg, Friendship, Cuba, Scio. The “story” then became about the people we found there.

The townspeople are very emotionally open and blunt in front of the camera, telling their stories. How did you find your subjects, and how did they come to trusting the film crew and telling their stories?

We worked hard early on to make ourselves very visible in the community—we ate at the diners, went to the harvest festivals, went to church on Sunday, went to the football games. We followed up with everyone. Most of the time we were with our subjects we were not filming—instead we were helping cook dinner, cut firewood, hiking in the woods, sharing our stories too. I think being brother and sister made us immediately accessible, people trust and understand family dynamics and we were allowed to be ourselves. In the end, the tone of the film is very intimate and very honest because the subjects were talking to someone they knew on the other side of the camera. I am really proud that we were able to maintain that trust throughout the entire process and that it reads to the audience as well.

What was the financing like for the project?

Financing this project was rather tricky. When we began fundraising, I was a 20-year-old first-time director writing and budgeting a documentary that wasn’t a social issue film, so it was difficult to attract grant money. Most of the financing came either in the form of out-of-pocket expenditures or individual and in-kind donations. IFP supported the project early on through fiscal sponsorship, which encouraged giving on many levels. NW Documentary, a non-profit in Portland, Oregon offered me an artist-in-residence position during post-production, and having an edit station, office space, and other creative minds with whom to share the process was invaluable; however, without formal funding, we had to constantly find creative ways to keep our costs low and remain patient. It was a healthy challenge.

In some filmmakers’ hands, they would present the people of Allegany County as either folky simpletons, or backwards country folk, or even look on them pitying for being working-class. Twelve Ways to Sunday does not take that pretense at all, celebrating the characters and uniqueness that the people are, and how gorgeous their home is (which is shot in wide panoramic shots). What do you think it is about the county that brings out the strength and humility in its people?

When we began filming, I was expecting to tell a story about a disappearing community. The Americana story that examines poverty and hardship and perhaps is full of romantic idealism for rural life. However, good documentary filmmaking is less about hunting down the story you have from the start and more about gathering the story as it unfolds before you. It requires patience and the ability to be surprised. What I found in Allegany County was an overwhelming sense of life, humility and self-reliance. Despite the economic depression in the area, I was met with a generosity that I had never before encountered. In the end, TWTS is more of a celebration film than anything else. I think that if you spent time in any small town you would find people that amazed you, inspired you, people that saw life if a poetic way, it’s just a matter of taking the time to get to know those folks.

Rooftop Films in NYC has been such a great showcase for independent films for the last 14 years. How did you become involved with them? Was it through IFP’s 2009 Documentary Filmmaker Lab, or did they contact you separately?

I met Mark Rosenberg, Artistic Director of Rooftop Films, last year during Independent Film Week. Rooftop hosts a preview screening of clips from that year’s Filmmaker Labs, and my trailer screened underneath the Brooklyn Bridge during that showcase. I actually gave Mark Rosenberg a jar of homemade jam (my budget marketing campaign!) that evening. I was already a big fan of what Rooftop is able to accomplish and I thought my film would find a welcome home with their programming. He checked out our rough cut through the DVD library at Independent Film Week and jumped on as an early supporter of the doc. We couldn’t be more ecstatic to be premiering with them.

On your blog, you mentioned that you became inspired by Mary to be more self-sufficient, and canned your first jar of preserves. What else did you take away from the filming, and what do you hope audiences will learn as well?

I drew much inspiration from the Foxfire book series, an anthology of oral histories that “promotes a sense of place and appreciation of local people, community, and culture as essential educational tools.” (The Foxfire Fund, Inc. Mission Statement, http://www.foxfire.org) I am hoping that the finished film will encourage and inspire discussions about rural America as well as celebrate living people as sources of disappearing knowledge.

What projects are you currently working on now?

I am currently developing a feature documentary examining the physical and physiological effects of shift work on body and mind. It is a character-driven film that follows the life of a nurse who frequently rotates between night and day shifts. I’m also working on a script for a narrative feature. It is about a young Chinese woman who has the opportunity to immigrate to the U.S. after her sister passes away during childbirth. She moves in with her sister’s widower to help raise her newborn niece. They live in a fairly small town in (surprise) upstate New York. The film is about being a novice, new life to the world, new immigrant to a country, and new outsider in a small town. I’m really excited by both non-fiction and fiction formats, and it seems organic to want to direct in both genres.