Back to selection

Back to selection

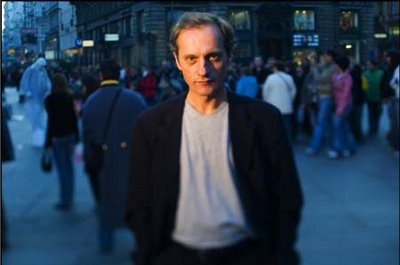

Götz Spielmann, Revanche

Contemporary Austrian cinema has been dominated by the works of its two best known names, Michael Haneke and Ulrich Seidl, but now the name of the prodigiously talented Götz Spielmann can be added to that list. Spielmann was born in 1961 in the town of Wels, but grew up in the country’s capital, Vienna. As a child he was drawn to film and he began writing and directing in his teens; when he was just 17, he had his first film shown on television. Between 1980 and 1987, he studied film at the Vienna Film Academy, part of the University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna, where his professors included the directors Harald Zusanek and Axel Corti. Having already made a number of award-winning student shorts, Spielmann made his feature debut in 1990 with Erwin und Julia, a tale of Vienna’s disaffected youth, which he followed up with 1993’s Der Nachbar. In 2000, he returned with The Stranger, a gritty depiction of the darker side of Vienna, which was chosen as Austria’s submission for the Best Foreign Language Film award at the Oscars. That same honor was also bestowed on his next film, Antares (2004), a triptych of interlinking stories set in a Viennese apartment building. In addition to periodically making films for TV, Spielmann has recently also begun writing and directing plays at the Linzer Kammerspiele in Linz, Austria.

Revanche, Spielmann’s latest film, is his third consecutive feature to be submitted by Austria to the Academy Awards and was one of the five nominees for Best Foreign Language Film this year. The set-up for the film is simple and familiar: Alex (Johannes Krisch), an ex-con minder at a Vienna sex club, is secretly having an affair with Tamara (Irina Potapenko), one of the Eastern European prostitutes under his care. To pay off both their debts so that they can escape to a new life together in Spain, he plans to rob a small town bank near his grandfather’s farm outside the city. Though its title and relatively conventional film noir beginning suggest a straight-up thriller, Revanche is in fact an incredibly nuanced and thought-provoking film which takes us to unexpected places in its profound examination of the themes of guilt, love and revenge. Spielmann weaves together elements of noir, Greek tragedy and pastoral in a perfectly paced and structured film which feels utterly real and organic. It is a beguiling piece of cinema, and it is unlikely that a better film than this will be released this year.

Filmmaker spoke to Spielmann about his writing process, the film’s organic nature, and his take on Hollywood cinema.

Filmmaker: What was the starting point for the film, and how did you first get interested in exploring these ideas?

Spielmann: I must admit that for me it’s always quite difficult to really analyze what the starting point was. Finding stories and ideas in which I really believe is such a complex and somehow chaotic process that I never can say where one story started and another ended. In this case, I found a sketch of the plot which I had written some years before but had put away because at that time it didn’t interest me anymore. It was one of those ideas that you’re interested in and you try out: you makes notes and make a sketch of it for a few days, but then it doesn’t feel interesting enough and you put it away and go somewhere else. When I read it, I was thrilled because I felt that there was something which has a lot to do with ancient tragedy in that plot, and that made it really rich and interesting and full, and then I started to work. Of course, there are other routes and sources for that: one is that about a year previously, I made a 10-day trek through the landscape where we then shot the movie, walking alone and thinking about stories and what I wanted to do. Another, for sure, is that I did a lot of research about prostitution some years before, which led me to the Ukraine. I researched that in Vienna and Eastern Europe, where a lot of the women come from. There are always a lot of sources that have to come together so that the river of the story can be filled up with energy and material.

Filmmaker: Once you’ve managed to tap in that river, do you write quite spontaneously?

Spielmann: I would say it’s a hard struggle to get to a point where I write spontaneously, and at that point it’s easy. But every day, it’s a struggle to get to that point because, in my opinion, real or honest creativity has to do with an empty mind, and the work and the struggle is to get there every day. Sometimes it takes half an hour, sometimes it takes three hours when writing a script, but when I’ve found that point it’s very easy and very refreshing to write. So it’s half a struggle and half a holiday. [laughs]

Filmmaker: So when you’re in that mode of having an empty mind, is what you write is coming from somewhere subliminal?

Spielmann: I think that “subliminal” is a good word, yeah. Let me say it this way: I think we have two energies or two intelligences. We have a small one that’s consciousness, and a big one – an enormous one, very precise, knowing many things much more than our consciousness could dream of – which is maybe below our consciousness or above our consciousness. Maybe it’s around it – I don’t know. And I think that the really important things in life happen in the big intelligence and not in the small intelligence of intellectuality.

Filmmaker: Revanche is so beautifully paced and structured, so can you tell me about the process of achieving that?

Spielmann: It was not easy. It was quite complicated because there was the danger that the movie would fall into two pieces, so it was a lot of work. In this case, the process of writing means to analyze the problem, to know what has to be solved, and then wait until the solution comes. So part of the work is conscious and analysis and intellectual; I have nothing against that because it’s a perfect tool, but it’s not more than a tool. It has nothing to do with the truth or real things, so it was quite hard work to find the structure. It was tricky, but I’m happy that the audience don’t realize that it had to be tricky, because I think that the real, beautiful things seem to be very easy – and it’s a hard struggle to get to that simplicity.

Filmmaker: The opening image of the film is of ripples breaking on a placid lake, and the film itself seems to be about the ripples caused by a single event. Is that the reason you used it?

Spielmann: Yes, and no. Yes, because that sounds a very useful and truthful thought to me, and no, because it’s a picture not an idea, and a thought or an idea followed. The picture came first and I somehow felt that this was the beginning. It was an instinct. I would lie if I say that I write calculatedly; I don’t.

Filmmaker: It seems like Revanche plays with the conventions of film noir, so I’m interested to know your feelings on the genre.

Spielmann: I like it, I would say. By the way, it was quite influenced by Austrian and German directors, and the basic root of film noir is the so-called German Expressionism which was very strongly influenced by Austrian artists, so film noir seems to be something that has its roots in Austria and Austrian culture. But, on the other hand, I never think in genres when I work because I just try to make personal movies as good as I can. Certainly I’m influenced by everything I’ve seen and everything I’ve read, but I don’t care about that. I have no problem in being influenced. I don’t feel any need to be something outside the world; I’m part of it, so I’m influenced, but my working process and my goals never have to do with genre. So that influence just happens.

Filmmaker: My reaction to the film was that it begins with a classic film noir setup, but then takes us in an unexpected direction. Even the title seems to give us expectations of a more conventional revenge film.

Spielmann: I didn’t think about that, not really, but then maybe I just started simple. My mind is simple at the beginning and during the process of working it’s getting more complex. Maybe it’s so easy that maybe clichés are in my head, but when you look with care and with concentration at a cliché it shows its hidden truth. So maybe that happened, but I never thought to to manipulate the spectator.

Filmmaker: “Manipulate” is a much stronger word than I would use.

Spielmann: You know, of course, there is a lot of conscious and unconscious trickiness in telling stories. There’s structure and you work with tension and you work with expectations when you tell a story. Everybody does that, and I am not an un-tricky writer. So, on the surface, that’s part of the work, but what I’m trying to say is that the profound importance is to get over that, to go deeper than that and be more exact than the manipulating methods cinema allows. By the way, one of the basic longings for the style in which the movie was made was not to manipulate. That’s the reason there are so few cuts, why there is no film music at all to give the spectator his or her own freedom in being touched or not and not to manipulate the emotions. That can be very easy if you know how to make movies but which, in my opinion and from my personal experience as a spectator myself, doesn’t create emotions that last. Those emotions that are evoked from manipulation don’t lead to a need, they don’t make a big experience, and my longing and my goal is to create experiences for the audience, not manipulations.

Filmmaker: The film does feel incredibly organic…

Spielmann: A beautiful word.

Filmmaker: …And spontaneous and unforced. How did you achieve that effect?

Spielmann: [laughs] Yes, that’s a very big question, my dear, [laughs] because it has to do with a lot of things. It first of all has to do with writing the script, especially dialogue, it has to do with the work with actors, it has to do with the work with the camera, with the pictures. All that has to come together to find that organic (I like that word very much) form, finally. I would say in general I work with a very precise knowledge of what I want from each single scene and each sentence an actor says and of each single picture, and on the other hand I wait as long as possible to reach that goal. That means when I shoot a scene, I know what feeling and energy and emotions should be in that scene, but I decide at the very last moment how we’ll do it and how I’ll shoot it. That allows me to stay inspired by everything that happens, by the actors, by the people I work with, by the locations, by the weather, by the light, by the noises I hear – by everything.

Filmmaker: Does that mean that you encourage your actors to improvise?

Spielmann: I work with improvisation in the rehearsals. I rehearse a lot. I rehearse about two weeks with the actors before we shoot. In that process, I sometimes change some dialogue. When I see in rehearsal that an actor can not do it in the way I want it, then I change the dialogue, or if there is an improvisation that makes it more interesting then I put it into the script. But that’s not needed: if that doesn’t happen, there’s still an idea in the script and a scene that works. When I shoot, I very seldom work with improvisation, only in situations of a high emotional energy level, for example the bank robbery. When I shoot, it’s very precise.

Filmmaker: Has the rehearsal process, and other aspects of your filmmaking practice, been influenced by your theater work?

Spielmann: Not at all, not at all. Theater refreshes me very much, it makes me fresh and full of energy. It’s something I love to do. If you have a really good play, a masterpiece, it’s just refreshing to work with that, to understand it better and better during the process of rehearsing it. I like to work with actors and I like work that vanishes very quickly afterwards. When you make something for the theater, three months after the opening, it’s gone, it’s away most of the time. I like that. It’s something which is a good opposite to the writing process, which has a lot to do with being alone, and sometimes being lonely, and working on theater is the opposite, it’s working together. It’s really a kind of fun which I do with a lot of passion and seriousness. So fun not in an un-profound way.

Filmmaker: If you like how theater disappears, does the permanence of films make you feel pressured? Do you not like that permanence so much?

Spielmann: I like it very much and wouldn’t say that it’s pressure, but another kind of responsibility. I like that responsibility as well. I like both. I like the lightness and I like the responsible things.

Filmmaker: Do you see Revanche as a typically Austrian film? How do you view it in the context of a national cinema?

Spielmann: For me, that’s hard for me to say because I’m Chinese and I more see the differences between us Chinese. [laughs] I don’t look at us from outside so I don’t think we’re all the same. [laughs] I don’t know, I really don’t know. I like some filmmakers here very much, in some aspects I’m influenced by Austrian culture and Austrian tradition. But, on the other hand, I don’t feel like an Austrian artist, I feel more like a citizen of the world, or maybe of Europe. Austria’s a very small country, so for an artist’s self consciousness or self definition, a country alone is too little to define yourself by.

Filmmaker: You said you’re a citizen of the world, so does that mean that you might consider doing a film outside of Austria? Have you considered doing a film in the U.S.?

Spielmann: That might happen, yes, but I cannot say. It depends. If the project, the script and the circumstances of working give me the impression I could make something beautiful, then I would do it, yes.

Filmmaker: If you could travel back in time and be able to make movies in a time and place of your choice, where and when would it be?

Spielmann: It would be between 1950 and 1965 in Europe, maybe Italy, with what emerged from the neorealists. For me, the mid 50s to the late 60s in European cinema is the most interesting part of film history.

Filmmaker: Is Hollywood going in the right direction?

Spielmann: I have the impression, yes. In my opinion, it opens itself more and more to a cinema which is not a kind of commercial easy listening.

Filmmaker: Finally, what’s the smartest decision you ever made?

Spielmann: To get born.