Back to selection

Back to selection

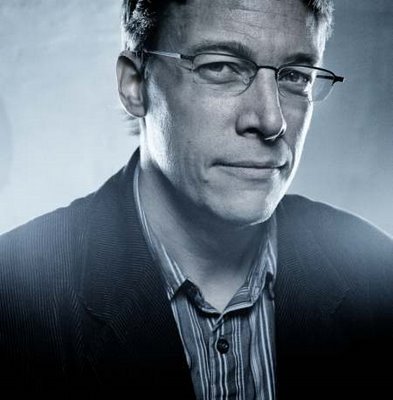

Anders Østergaard, Burma VJ

Danish cinema currently has numerous talented fiction directors – everybody from Lars von Trier, Christopher Boe, Ole Bornedal, and Susanne Bier to Thomas Vinterberg, Kristian Levring, Nicolas Winding Refn and Lone Scherfig – and now Anders Østergaard is bringing attention to the country’s documentary output. Born in Copenhagen in 1965, Østergaard studied at the Danish School of Journalism, graduating in 1991, before deciding to eschew a career as a journalist to become a documentarian. Throughout his career, he has been concerned with the boundaries of non-fiction and with the idea of documentary itself. Østergaard’s debut film, Gensyn med Johannesburg (1996), was about filmmaker Henning Carlsen’s return to the eponymous South African city, where 35 years earlier he had shot the docudrama Dilemma. Since then, Østergaard has become particularly interested in documentary reenactments: he recreated the death of Swedish jazz musician Jan Johansson in Troldkarlen (1999), and in Tintin et Moi (2003) he used 3D animation to explore the previously two-dimensional world of Hergé’s cartoons. In 2006, he scored a big hit in his home country with Gasolin’, a portrait of the Danish 70s rock band of the same name, and in 2008 followed it up with Så kort og mærkeligt livet er, about Danish poet Dan Turéll.

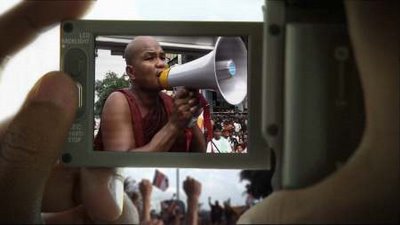

Østergaard’s latest film, Burma VJ, once again grapples with how and why we capture the world on film. It was initially meant to be a small-scale film about “Joshua,” a junior video reporter living in Rangoon, the largest city in Burma, who is part of the Democratic Voice of Burma (or DVB). Though any journalistic activity is banned under the current Burmese junta, the DVB risk their lives and freedom to secretly document government suppression in the country so that its own citizens, as well as the international community, can see. However the project changed radically in 2007, when, after 19 years of relative quiet, the Saffron Revolution – an uprising of the country’s Buddhist monks – took place, turning the film into a document of the Burmese people’s attempt to fight back. Narrated by “Joshua” and featuring reenactments that depict his role in these tumultuous events, Burma VJ brings out the powerful dramatic aspects of this true story in a way that rivals any fiction film. However, it is ultimately the purer documentary elements – the immediate, electric footage shot by the DVB video reporters – which make Burma VJ a compelling and important piece of cinema.

Filmmaker spoke to Østergaard about his penchant for reenactment, the blurring of the line between fiction and documentary cinema, and why he wishes he’d directed 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Filmmaker: You studied journalism rather than film, so did that background give you a different perspective on the way that you approach filmmaking?

Østergaard: That’s very likely. Of course I’m in documentary, which is related to journalism and there’s a lot of method that is shared with journalism. Also, I’m very keen on research – understanding an issue before I describing it – and I would less on intuitive or subjective understanding. But on the other hand I’ve deliberately chosen not to work in journalism; I take liberties in my films which you can not take in journalistic. There’s an element of reenactment in this film, for example, which defines it as something different.

Filmmaker: Reenactment has been a part of your work for some time now. What particularly attracts you to using it in your films?

Østergaard: It’s a great science to recreate the past, to make the past come alive, to be there as much as possible. This leads me to do a lot of reenactments, but I’m always happiest when there is some authentic or original element to the reenactment, like a sound bite which I can then build the texture around. Basically I want to tell stories which have the full cinematic flow, the feeling of being there as a cinemagoer, just like any feature film. And in order to achieve that narrative flow, you need reenactment.

Filmmaker: With this film, were the phone conversations one of the original elements that you built the reenactments around?

Østergaard: Some of them are original, others are reenacted but on the highest level of factuality. I would call them “self-constructions,” in the sense that it was the real protagonists who relived their conversations some months after they took place.

Filmmaker: How did those subjects feel about acting out those conversations again?

Østergaard: I think it was therapeutic for them to relive these dramatic, sometimes traumatic, experiences, as a way of letting the steam out, so to speak. They had build up stories and experiences individually, but they didn’t have much chance to discuss it between them because of security reasons, because of the chaos of the aftermath of this uprising. Most of them hadn’t been in a situation like this before: they had been growing up in a country where absolutely nothing was happening, and all of a sudden they were thrown into revolution. I think it was an opportunity for them to digest what they’d been through. I could feel that very often in the conversations, that the whole emotional energy was completely intact.

Filmmaker: Did they feel as if they were acting?

Østergaard: Yeah, acting, but of course we were often very successful in getting back to those feelings. I started off by getting them to talk about what they’d been through and looked for keywords or phrases in their accounts, things I recognized as emotional triggers in their conversations, and I then reminded them to use this or that keyword. I learned that this was something that would lead back to those original emotions. Like “I escaped death twice today”; it’s very important to keep to that expression, because that’s the emotional trigger for everything. It’s a very powerful statement.

Filmmaker: You said that what you were aiming for was something similar to narrative cinema. Do you feel as if the line between documentary and fiction filmmaking is blurring?

Østergaard: To some extent. When you have this narrative ambition, you will of course get closer to the language of fiction films. I’ve been working with this for quite some years now and a lot of my colleagues are doing that as well. It’s not that we want to tell lies, it’s not that we want to fictionalize the world. It doesn’t allow us to make up stories that never happened. What we’re trying to do is take factual events and represent them as richly and as directly as we can; that’s why we resort to reenact.

Filmmaker: Can you tell me about the initial idea you had for Burma VJ and how that then evolved into the film that you actually made?

Østergaard: We started off with quite a small project about Joshua’s daily life as a street reporter and the difficulties of getting any interesting material at all because of the obvious hazards and risks of bringing out a camera on the streets of Rangoon. We were going to have quite modest footage from his side and then add his own world to it in his own narration. It was going to be a little 30 minute festival thing. In the midst of this, there was this incredible coincidence [of the Saffron Revolution happening]. At the time that we met him, Joshua was a junior member of the group and not high profile or experienced. Suddenly, he was thrown into events in the way the film recounts, and he became a catalyst for bringing news in and out of Burma to the world media, which was an incredible rite of passage for him.

Filmmaker: How did you initially make contact with him?

Østergaard: It was fairly straightforward, in that we contacted the Democratic Voice of Burma in Oslo and from the beginning they were extremely trustful and inviting about us doing the film. They brought us to Bangkok, where we were able to meet 10 or 12 of those supporters at the time – this was already early ’07 – and among them was Joshua. I slowly figured out that he might be our protagonist, because of his many qualities.

Filmmaker: How easy was it for you to get Joshua to agree to appear in the film?

Østergaard: I think at first he was apprehensive about having to take on this. He did it for the cause, but I don’t think he was so keen about sharing a life that was already nerve wracking. How would he know that we would take care of his information? But instinctively he was keen to talk about that and to share his life and experience with the outside world. He had this drive in himself, and this was very much the reason he was a good protagonist and why the film feels personal and rooted in something. It’s because he has his own desire to communicate with the outside world.

Filmmaker: How did you work out the way to frame the footage you got from the Burmese video reporters?

Østergaard: I think one important lesson was not to be slaves to the footage, that the footage was not going to decide the story, even if it was very exciting or unique or dramatic. The footage must serve the story, the one that I organized out of my understanding of the narrative of that uprising, the different emotional stages. Basically, the film is about battling and conquering your own fear; that’s a situation that goes on every day inside a Burmese person. In order to have the psychological stages [of the Saffron Revolution] clear and well narrated, you can’t say “Oh, we must have this scene also, because it’s very interesting footage…” You have to direct a lot to have that clear story, and that’s where the phone conversations were very helpful in giving you that psychological lens to what was really going on and how it felt.

Filmmaker: The film is narrated by Joshua, so did he write the narration himself? And was he involved in postproduction at all?

Østergaard: It is a mix of original, spontaneous interviews, with the good old technique of cutting out my questions and asking him to give independent answers. That accounts for maybe 60% of the narration. Of course, we had to rewrite passages for the sake of clarity or legibility of language. He’s got a very rich vocabulary but he’s self-taught, and sometimes he achieved a poetic idiom, a poetic way of putting things which I deliberately kept for the feel of it, because the film is extremely expressive. “We have no more people to die,” for instance. This is grammatically completely incorrect, but very beautiful. As he was exiled, he was at hand to work with us after the uprising, so he was often almost an assistant director to me in the reenactments, making sure that all the facts were correct, or that people looked like they did. I was keen that it would be his story, truly and fully his perspective on things.

Filmmaker: Once you were nearing the end of postproduction, what were your hopes for what the film might achieve in terms of a real world impact?

Østergaard: To be honest, there was a lot of pressure to get the film done in time, it was a very complicated to make, and we were very focused on that. You don’t know how a film will work until it’s out there. Not really. But, of course, we told each other this was going to be big, and the drama of the happy times and the miserable crackdown was very powerful, and that it would give a second life to this footage. It had already been broadcast as news, but this context we were able to offer to it gives it a new perspective.

Filmmaker: Do you see the film as a political statement?

Østergaard: In fact, I’m not sure it’s really political, [laughs] because the level of evil and the level of goodness on either side is so great. Of course, it has political purpose, it has a political function to raise awareness about the Burmese issue, but the film isn’t really political because it isn’t debating anything. How can you debate the Burmese regime? It’s a bunch of gangsters. How can you defend them? There’s no two angles to the story – believe me, I’ve looked. It’s almost a mythological investigation of good will and bad will. I didn’t think much of politics when I was making it. I tried to look into the almost existential questions about why you would take such a risk without being rewarded, how you keep faith and how you conquer your fear.

Filmmaker: How do you view this film in the context of your other work?

Østergaard: It’s certainly different. You could say it’s something that just happened to me. To be involved in an issue with this kind of political energy or urgency was entirely unexpected and so I’m trying to understand what a film can be, how functional it can actually be out in the world. That’s of course a very rich, privileged experience.

Filmmaker: When was the last time you wished you had a different job?

Østergaard: I’m sure the last stages of editing. You’re sick. I was under a lot of pressure: I was stuck in the editing room all summer, I could hear people having fun downstairs in a restaurant on the street, it was boiling, and we were panicking as always about how to open the film.

Filmmaker: Which film do you wish you had directed?

Østergaard: 2001 is to me such an ultimate exercise. It’s an incredible film, but the idea of me making it is pretty absurd. [laughs] But a film that becomes a universe in itself where you actually build a space lab in order to make it… The production story is quite amazing, and the level of research too. The ability to simply transcend the norms of the genre, to make a computer the main character and those kind of very daring moves still astounds me.

Filmmaker: If you could travel back in time and be able to make movies in a time and place of your choice, where and when would it be?

Østergaard: The 18th century, for its expressiveness. I would do a documentary on Bach when he was still alive. [laughs] He was a magician, an extraordinary talent, and I’d just need to follow his frenzied production.

Filmmaker: Finally, What’s the thing you keep on forgetting to do?

Østergaard: Take notes on my ideas. I have this stupid idea that if an idea’s strong enough, I’ll remember it. Which I won’t.