Back to selection

Back to selection

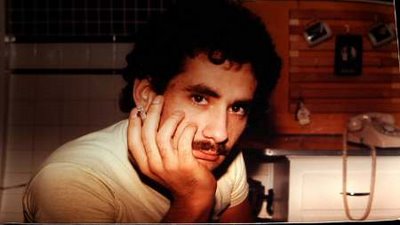

Daryl Wein, Sex Positive

Most young filmmakers quickly define themselves in terms of both their creative roles and genre specialties, however Daryl Wein has so far benefited from doing exactly the opposite. Born in Santa Monica in 1983, Wein grew up in Connecticut and commuted to auditions in New York City as he pursued a career as a child actor, mostly in commercials. At the same time, Wein’s father’s interest in chronicling their family life on home video lead the young thespian to become fascinated with being on the other side of the camera. At the age of 16, he made Life is a Train, a short film which won him an award at the International Young Filmmaker’s Festival in New York, as well as the inaugural You Belong in Connecticut Young Media Maker Award. He went to NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts to study drama and film, and also appeared in small roles in the films Magic Rock (2001) and The Hebrew Hammer (2003) as well as the Comedy Central TV movie Porn ‘n Chicken (2002). In 2007, he co-wrote, directed and edited the short film Unlocked, starring Olivia Thirlby and executive produced by director Stephen Daldry, which played at the Tribeca Film Festival. Wein’s first narrative feature, Breaking Upwards, which is based on Wein’s relationship with actress Zoe Lister-Jones and features the pair playing versions of themselves, premiered at SXSW earlier this year.

It is demonstrative of Daryl Wein’s openness as a filmmaker that, despite his strong acting background, his first feature length film is, in fact, a documentary. Sex Positive is a portrait of Richard Berkowitz, a figure now penniless and forgotten, who was a fearless and controversial AIDS activist in the 1980s and, along with Dr. Joseph Sonnabend and actor Michael Callen, one of the architects of the safe sex movement. Berkowitz was hugely unpopular for his contention that the AIDS epidemic was exacerbated by the gay community’s promiscuous lifestyle, however, he responded to accusations of being “sex negative” by proposing that responsible actions, such as condom use, should not inhibit sexual activity. Sex Positive has the virtue of not only telling an important story but having, in Richard Berkowitz, a fascinating subject truly worthy of scrutiny. Berkowitz is a compelling presence who talks candidly about not only his activism and his own battle with AIDS but also his time as an S&M hustler and drug addict. Wein ably balances historical background and his focus on Berkowitz, while the handsome work by DP Alex Bergman adds further character to the piece.

Filmmaker spoke to Wein about his discovery of Berkowitz’s story, the blurring of documentary and fiction, and why he was recently sitting naked on a unicorn.

Filmmaker: Tell me about the starting point for this film.

Wein: I met Richard Berkowitz at a Passover Seder in 2007. He is really good friends with my girlfriend’s mother; they’ve known each for 20 years. It was a gathering of lots of progressive types at this thing and at the time I’d just graduated from NYU a year before and I was looking for my next project. (Before I’d done a short film that was at the Tribeca Film Festival.) I was happy to do documentary or fiction, I just wanted something that I felt passionate about. Zoe, my girlfriend, said, “You should really meet Richard because he has an incredible life story – he used to be a sex worker and he was a controversial AIDS activist.” I said, “OK, that sounds interesting,” and then I spoke with him and he was very sweet, and I could tell he had a lot to say. [laughs] Then I read his book, Staying Alive: The Invention of Safe Sex, and I think that’s what really did it for me. Reading that, I realized “This is such an important story, and such a fascinating slice of history that I don’t know anything about.”

Filmmaker: Did you become friends with Richard before you had asked to make a film about him?

Wein: Not really – we kind of started right away. He had an implicit trust in me because he knew I wasn’t a complete stranger who was going to exploit him and his story, because his lifelong friend’s daughter was my girlfriend. That allowed him to trust me, and I think also Richard had been waiting for someone to give him the opportunity to share his story again. He’s had so much trouble getting his writing out there and so this was a really good chance for him to just rehash a lot of the old ideas. I just wanted to start right away anyway. Of course, at first I thought I probably should get to know him and be familiar, but the second he started talking, everything that came out of his mouth was so brilliant. It was amazing sound bites from the first interview, which was five hours long and actually is the interview I ended up using as the basis for the story.

Filmmaker: What was your motivation for the film? Did you see it as a character study? Were you more focused on the LGBT angle? Or were you trying to make a case for Richard Berkowitz’s historical significance?

Wein: I would say that first and foremost it’s a portrait of Richard’s life, but I think from that it opens up a door to a lot of other areas. I was interested in exploring all of the early history surrounding the controversy around HIV and AIDS theory. I was kind of enraptured by all of it, I thought was really interesting.

Filmmaker: Were you already aware of or interested in LGBT issues?

Wein: No, I didn’t have any specific interest in the LGBT community, it wasn’t an area I had done any film work in the past. It was totally new to me. I’m a straight young filmmaker and Richard’s in his fifties and gay, so everyone wonders how we come together. It’s funny, Richard always says it had to take a straight guy to make this story, because he doesn’t know why a gay man hasn’t made this yet.

Filmmaker: The film is very personal and you get a real sense of the trust that developed between you and Richard, but there are also times when you push him to be more revelatory, specifically to do with his hustling and more sexual aspects. How easy was that for you?

Wein: I guess he was pretty open with everything. I think what was difficult was he didn’t want to feel like parts of his life were being taken out of context, like I was doing an Enquirer version. His sex work was an extremely touchy subject, and there was a point in time when I felt like I could make this whole movie about Richard as a sex worker. It really is its own story. And there was also another point at which I felt like I could probably just cut this altogether. But I think it’s so important to show that he was deeply immersed in that world, and it’s that world that lead him to meet Dr. Joseph Sonnabend and begin to take action as an activist and really understand what was happening medically and scientifically. He was experiencing all that firsthand, he had thousands of gay men coming into his apartment while working as an S&M top, and so I think that’s what really set him apart.

Filmmaker: How does he feel about those aspects of the film, and also the bits that deal with his drug use?

Wein: I think it’s hard for him to see them, but I think Richard prefers to be portrayed as a complex person. He doesn’t want to leave anything out. He doesn’t want to be portrayed as a total saint, so he understands that showing some of the dark patches is important. I mean, he says in the movie that the reason he was doing all those drugs was to numb all the pain and there were times when it became so hard he just couldn’t resist.

Filmmaker: How did Richard view this film? Did he see this as his chance for redemption, or is that too melodramatic an interpretation?

Wein: I think he definitely saw this as a chance to redeem himself and receive some credit that was due. I think it was also another chance to try and promote the cause that he was originally espousing with Michael about safe sex. It’s such a convoluted history: even if you go online and type in “the invention of safe sex,” the chances are you’re not going to find any kind of concise story or version of it. I think now, with this film and his book (which he’s written a new forward to), and all the film festivals he’s going to and the people he’s talking to, he can get back to what he originally was professing about importance of safe sex, which a new generation might not know about. I think we both feel that’s a crucial part of history that may be lost if we don’t work hard to really try and clarify aspects of it.

Filmmaker: Documentaries, particularly first features, often do not put a high priority on good visuals, but Sex Positive looks really great. How important was that to your vision of the film?

Wein: Well, I have to mention my director of photography, Alex Bergman, who shot it for me on the Panasonic HVX200. It’s an HD camera but we used 35mm lenses so it gave it that depth of field to make it feel a bit more filmic, because I can’t stand that sharp video look. We did the best job we could to make it cinematic feeling. The decision to be handheld and not like completely locked down was just to give it an extra sense of rawness and authenticity, and we did color correct it, which I think helped bring out the richness of the different interviews.

Filmmaker: This is a documentary, you’re an actor as well, you’ve now made a fiction film also, so how do you describe yourself to people?

Wein: I would say I’m first and foremost a filmmaker. I went to NYU for acting and I used to act more, but I’m not really interested in acting. I acted in Breaking Upwards because that was about my relationship with Zoe in real life and it made sense because of our chemistry together and I thought it would be more interesting if we played ourselves as opposed to hired two actors. But I just really want to focus on directing.

Filmmaker: You said Breaking Upwards is about your relationship with Zoe Lister-Jones, but it’s a fiction film in which you two play characters called Daryl and Zoe. It seems as if you’re playing with the divide between documentary and fiction filmmaking.

Wein: There’s a lot of elements in that film that are based in reality, but we fictionalized all of it, for the most part. Zoe and I really did experience an open relationship similar to that, we did sit down and strategize and come up with rules to try and eventually break up or take a break or whatever. There are some people in the film, friends of ours, who are our real friends who are not actors, but we didn’t really want to call attention to what was real or wasn’t real, we just wanted to leave that up to the audience’s imagination to try and deduce. I think it helped give the film a sense of authenticity. But it’s all kind of a blur, that fact-fiction thing.

Filmmaker: So after these two films do you feel like there’s a logical next step for you as a filmmaker?

Wein: Zoe and I just finished writing a political thriller about the future of genetically modified food in America. We’re just now trying to put that together. I don’t want to do one thing, I just want to tell stories that seem relevant and important now to me and it’s fun to jump into different genres and different forms. If there was another amazing documentary story that just fell into my lap, like this one did, I would probably pursue it.

Filmmaker: I saw your short film, Unlocked, which I noticed was produced by Stephen Daldry. How did he get involved with that project?

Wein: I worked for Stephen Daldry as his assistant when he was putting together Billy Elliott [on Broadway]. I showed him Unlocked and we became friends, and he said, “Anything I can do to help…” So he came on as an executive producer, and that was just really cool of him, because I admire his work.

Filmmaker: Do you aspire to be making films in Hollywood like Daldry?

Wein: I just aspire to be able to make films that I want to make. If I can have the luxury to be able to make something that I’m passionate about, whether it be in Hollywood or independent, that’s all that matters. Obviously my roots are independent and all my films have been made that way; I’ve had to scrounge together people and money and I have been a producer on all of my films. I’ve worn many hats, which I like doing because it helps to have that control, it’s very liberating. But I also don’t like to wear all the hats all the time. [laughs] If I could have a big crew and other people to be able to help and be able to pay them, it would be absolutely great. So I would love to work in Hollywood.

Filmmaker: What’s the biggest compliment you’ve ever received?

Wein: Someone after one of the screenings at SXSW said that Sex Positive saved her life. I think she had two people in her life, very close family members, who had died of AIDS and the film and Richard’s story were such an inspiration to her that she felt like she could continue living. That was a pretty remarkable moment to realize that a film that I was making was actually making a difference in people’s lives.

Filmmaker: What’s your best piece of advice for aspiring filmmakers?

Wein: The best advice I have is just to do it yourself and just don’t be lazy. Get out there and try to make it work. And if you fail, great, you’ll learn along the way. Don’t be afraid to just do it. Don’t take no for an answer. If people don’t want to give you money or people don’t want to give you the opportunity, then say “Fuck it, I’m just going to get a camera and friends together and make it.”

Filmmaker: What’s the most embarrassing film you watched the whole of on a plane?

Wein: [laughs] Oh, God! It might have been Sex and the City. [laughs] It also may have been a rough cut of my own film, Sex Positive. There’s so much graphic material in it that I think the person sitting next to me was so weirded out. So one of those two.

Filmmaker: The Sex double bill – Sex and the City and Sex Positive. Soon to be available on double DVD.

Wein: [laughs] Sex Positive and Sex and the City, they go naturally together. [laughs]

Filmmaker: Finally, when was the last time you burst out laughing on set?

Wein: I think when we were shooting the rap video for the Breaking Upwards viral campaign. I had to pretend that I was sitting naked on a unicorn and we were laughing so hard when we were doing that. I was holding my privates, and trying to be serious, but we couldn’t really hold it together.