Back to selection

Back to selection

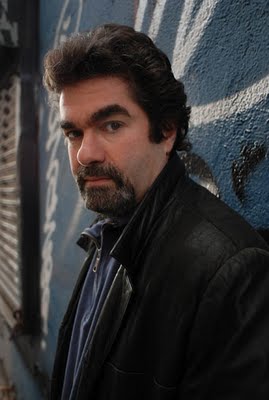

Joe Berlinger, Crude

Joe Berlinger is a filmmaker who makes documentaries that tell important stories with integrity, while still always entertaining his audiences. Born in Bridgeport, Connecticut, in 1961, Berlinger studied English and German at Colgate University, and got his first taste of the movie business while working on TV commercials at an advertising agency in Frankfurt. After deciding he wanted to make films, he moved to New York City, where he got a job working for the Maysles brothers. Berlinger’s first foray into directing was the documentary short Outrageous Taxi Stories (1989), and he made his feature debut in 1992 with Brother’s Keeper, a non-fiction film about a man accused of killing his brother, co-directed with Bruce Sinofsky. The film became a self-distributed hit for Berlinger and Sinofsky, and the pair returned to the subject of small town murder in Paradise Lost: The Child Murders at Robin Hood Hills (1996), which won huge acclaim and has become a cult classic. (A follow-up film, Paradise Lost 2: Revelations, was released in 2000.) Berlinger briefly moved into fiction filmmaking with Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2, which he co-wrote as well as directed, but returned to portraying real life extremes with Sinofsky on Metallica: Some Kind of Monster (2004), a documentary about the turbulent genesis of the iconic rock band’s album “St. Anger.” Berlinger is also active in television as the creator of such shows as Iconoclasts, FanClub and The Wrong Man, and the director of TV documentaries like Gray Matter and Judgment Day: Should the Guilty Go Free. Berlinger’s latest film, Crude, is something of a departure for the director as it presents a story on a much bigger scale than his previous documentaries. The film focuses on the horrific damage done to the Ecuadorian rainforest (and the impact on its indigenous inhabitants), and the efforts of oil worker-turned-lawyer Pablo Fajardo to hold the oil behemoth Chevron accountable. Crude has aspects of both the environmental documentary and the David and Goliath tale, but adds up to an even more intriguing film than it might seem on paper. Berlinger uses the case as a way of scrutinizing the inadequacy of the judicial system to handle such an incident, while also addressing other problematic aspects of the lawsuit such as Fajardo’s backing by a large legal firm that is bankrolling him purely for profit. While previous Berlinger movies such as Brother’s Keeper and Paradise Lost have shed light on a situation in the hope of affecting positive change, Crude shows progress being made in the case (Fajardo being backed by the Ecuadorian president and becoming a minor celebrity), but ultimately leaves viewers with the feeling that nothing – not even victory in the courts or a big payout from Chevron – will come close to putting things right. Filmmaker spoke to Berlinger about his decision to make an activist film, the dangers of going up against a corporate giant, and his love of Planet of the Apes.

Filmmaker: How did you first come across this story?

Berlinger: This was not something I thought was going to be my next film. My aspirations at the beginning were quite humble and in fact I found myself really not thinking I was going to make this film. I had a lot of hesitation about it. Steven Donziger, the plaintiff’s attorney, came to my office. Steven started talking about the case and all of my red flags went up because at the time I didn’t know there was a Pablo Fajardo, at the time I didn’t know there was going to be some present tense inspections – all I knew was that he was telling me about this 13-year struggle.

Filmmaker: Obviously, that was problematic to you because that set-up is hardly very cinematic.

Berlinger: Yeah, I’m a present tense, cinéma vérité filmmaker and it seemed like I’d missed the story. If it’s a 13-year legal struggle, how am I going to dramatize it? That was the first red flag, and the second red flag was this was a plaintiff’s attorney clearly with an agenda and I am not that kind of a filmmaker. My films are very humanistic. Brother’s Keeper and Paradise Lost deal with some very serious social issues, but I consider myself a storyteller first and a journalist second. I make these ambiguous human portraits and this was a guy who had a message and wanted to bang that message over people’s heads. I said, “I’m not sure I’m the right filmmaker for you. There’s Robert Greenwald, there’s Michael Moore – people who make films with a very specific and clear point of view, and I’m not one of those guys. I’m also not sure how to film a story that’s 13 years old – maybe this is a 60 Minutes news piece.” It didn’t have the right aesthetic criteria for me and the biggest thing was there was no central character. You need a good central character to get your teeth stuck into.

Filmmaker: And yet you got hooked by the story.

Berlinger: Steven’s a very charismatic, persuasive guy and he convinced me to take a trip with him. I said, “As long as you know I have lots of reservations, sure I’ll go. I’ve never been to the rainforest and it sounds like an adventure, but I’m dubious that this will be a film.” He just kept saying, “If you only see the pollution…” When I went down, it was 10 times worse than I imagined, it was far worse than he had explained. It was horrifying, I could not believe what I was looking at. Here is a place that’s supposed to be a paradise on earth, but there’s these noxious pits leaching shit into the environment – it was shocking. I just thought to myself, “This may not have the aesthetic criteria that I usually look for, maybe I won’t have a central character and maybe there won’t be present tense action, but I’m just going to start documenting this.” I felt like I couldn’t turn my back on these people, and that’s really why I started the film.

Filmmaker: How much of a factor was funding in your decision?

Berlinger: When Bruce Sinofsky and I made Brother’s Keeper, we rolled the dice, we maxed out 10 credit cards, put all of our savings into it, really took a chance – the typical story. Then we got into Sundance, won a prize and our careers were established. But ever since Brother’s Keeper, I swore I wasn’t going to do it again, so going down to South America, one of my biggest concerns was how I was going to fund it. But when I got home I thought, “Technology is so cheap, I own these little HD cameras, and what’s a couple of plane tickets? I’m going to just start making this film and not worry who’s going to pay for it, not worry about distribution.” So I threw myself into it and made a commitment that I’d go down there every couple of weeks and see where it went, while doing other things – like Iconoclasts, commercials and myriad other things – which gave me the financial freedom to do it. The funny thing is, once I allowed all my aesthetic and financial criteria to be thrown out the door, things started materializing in a very Zen-like way. On the second trip, I met Pablo Fajardo, a guy who just oozes credibility and authenticity. I was just awestruck by this guy. I knew I had a juicy character and I started feeling, “This could be something…” And then on the third trip, they started talking about these judicial inspections finally being approved. It’s only one phase of the trial, but in the movie it stands in as the trial and provides the thing I never thought I’d have, which is this great present tense device. How dramatic to have these lawyers in jungle gear arguing their cases in front of these pollution sites in the middle of the Amazon. During the first inspection, I thought, “This could be a movie.” But I have to be honest, during the entire process I was wondering, “Does an American audience really want to see this?” Even when I was cutting it, I was thinking, “I think this is good and important, but God knows if this is going to see the light of day.”

Filmmaker: How much do you feel your presence as a filmmaker had an impact on what transpired? I suppose it’s one of the quintessential questions for a documentarian.

Berlinger: Yeah, it’s a fascinating question that I’m endlessly interested in with all of my work, the Heisenberg principle of documentary making: do you change things by observing? As truthful as I think my films are, I’m a firm believer that no film is the objective truth about anything. With Metallica, Lars [Ullrich] has said many times that the cameras were like a truth serum, that had they not been there the therapy would have ended unsuccessfully and early and the band probably would have broken up. In Brother’s Keeper, I definitely feel like the making of the film brought more people out to support [Delbert Ward] and increase the level of support. With this film, however, I actually think the presence of the camera was truly invisible, because I didn’t make it known that I was a filmmaker. I was fearful for my life throughout the making of most of this film, so I did not announce who I was or what my intentions were, and I certainly didn’t let Chevron know I was making this film. We had a small crew and because there were a lot of NGOs (like Amazon Watch) and local media down there observing the trial, so I just kind of fit in.

Filmmaker: You always bring to your films nuance and complexity, and here you very interestingly juxtapose Steven, a toughened lawyer who coaches Amazonian Indians on what to say in front of the Chevron shareholders meeting, with the pure and untarnished Pablo.

Berlinger: What I like about this film is that I think it subverts many of the conventions of normal advocacy filmmaking. It’s really not about the lawsuit, it’s about a much larger issue. I’m not smart enough – I’m not a lawyer, I’m not a scientist – to tell you that Chevron has not wrapped itself up in enough legal technicalities that it might possibly prevail in the eyes of the law, but from the moral standpoint the culpability lays at their door. It’s a portrait of how we see justice in the world and the inadequacy of the legal structure to really handle these kinds of humanitarian and environmental crises, because the thing has gone on for 17 years and it could go on for another 17 years. The other way I think it subverts the conventions of advocacy filmmaking is that it allows Chevron to have their full say. I worked really hard to get them into the film, I thought it was really important. The reason is you want the audience to be presented with the pros and cons, weigh them, and come to their own conclusion as opposed to being lectured to. The film has all sorts of nuance and observations that you don’t usually find in this kind of a film. I think that’s why it works as a film.

Filmmaker: You said before that you were fearful for your life for much of filming. Were you afraid of what Chevron could do to you then? And what’s your relationship with them now?

Berlinger: I want to be very clear: I don’t think the executives in San Ramon would ever order a hit on a filmmaker. I’m not that jaded. Often the home office contracts with a local company that also contracts with local people, and sometimes those local people – in order to protect that chain of employment – take matters into their own hands. So that doesn’t mean Chevron said, “Hey, go knock off Joe Berlinger,” but the local people could easily say, “We don’t want this being exposed. We’ve got to take care of this guy.” Even if that just means roughing me up. I was very aware of those stories, and we were also a couple of miles from the Columbian border, where the FARC was very active, where drug runners are very active, where American oil industry executives have been kidnapped for ransom. I just wanted to fly beneath the radar. [laughs]

Filmmaker: You have interviews with Chevron staffers in the film. At what stage did you tell them you were making the film?

Berlinger: I waited until I felt like I had the film in the can. From about August 2007 until August 2008, I pursued Chevron. The jungle part of the film was done. They took it as a bad sign that I hadn’t told them, but I told them, “I was filming your lawyers, but now I want you to participate. I have your version of the story via the trial, but it would be much better if U.S. executives explained your position in English.” I sent them all my films, then delay, delay, delay. They missed every deadline I gave them. Finally round August of 2008, I said, “Look, the Sundance Film Festival rough cut deadline that I’m gunning for is mid-September. The movie is 90% edited, and I’m really down to the wire. I’d love to have you in the film, but you’ve got to make a decision.” So, finally, they said, “Yes, we’ll do the interviews.” They bought a hotel room suite, and they gave me the two people. The funny thing is, when we’re setting up, another crew walks in. I was like, “Are you guys in the right place?” They said, “Yeah, we’re here to do the Chevron shoot. We’re here to film you.” Then the Chevron media spokesman came in and said, “Yes, I hope you don’t mind but we’re going to film this so we have a record of it.” That was their way of putting me on notice. I thought it was very funny. It was kinda smart, it was their semi-intimidation tactic to say, “Don’t manipulate the edit, because we have a record of it.” Not that I would. That was joke – I didn’t need to manipulate it! [laughs]

Filmmaker: What was your cinematic epiphany?

Berlinger: I started off my career in advertising. I was a language major and because I spoke a bunch of languages I ended up getting this great job when I was 23 producing television commercials in Frankfurt. So I stumbled into being on a film set because of language skills, not because of desire to be a filmmaker. That job in Frankfurt took me to London every two weeks for coordination meetings with clients. One day I walked into a theater to watch a movie in Piccadilly Circus and I saw Birdy. I thought that was the most amazing film. I had been on a shoot and it was one of the first shoots I’d been on, and I thought, “Oh, my God, I want to tell stories!”

Filmmaker: Which phrase best describes your philosophy on life?

Berlinger: I don’t know if I have a phrase, but one of the reasons I wanted to make this film – and one of the single most important things I’ve learned over my lifetime and the thing that I most want to impart to my children – is that the good guys aren’t always who you think they are.

Filmmaker: What was the first film you ever saw?

Berlinger: There are two early formative films. My earliest filmgoing memory is actually Planet of the Apes, and that was a terrifying experience. It blew me away with its message. Believe it or not, the original Planet of the Apes is on my top 10 list. Maybe it’s just because I was a kid, but I’m sorry – and I’ve been ridiculed for this – one of the greatest moments in cinema for me is when the astronauts are in that field with the mutant humans, and the first time that they realize they’re going to get hunted down, and all of a sudden the apes appear on horseback. The original time that happened, that was one of the great moments in cinema. Then the first horror movie I saw, when I was nine, was Tales from the Crypt, which was a compendium. I recently saw it and the blood was so fake, I can’t believe it scared me. My father took a bunch of kids to that movie – I think I was probably too young to see it – and he just stopped the car and turned the engine off and turned the lights out in the middle of the road, just to scare the shit out of us. Then he got out of the car and ran around, and we were all scared to death.