Back to selection

Back to selection

“PROJECT NIM” DIRECTOR JAMES MARSH

During the past decade, some of the movies’ most crowd-pleasing moments can be found not in ballyhooed Hollywood blockbusters but in documentaries. Doc like Spellbound, Anvil: The Story of Anvil, and The King of Kong: A Fist Full of Quarters are best seen with an audience ready to cheer.

The most dazzling example of this trend just might be James Marsh’s Man on Wire, the exhilarating story of Phillipe Petit, a small Frenchman with big dreams. Marsh recounts how the daredevil Petit strung a wire between New York’s Twin Towers and then proceeded to dance between the two skyscrapers — perhaps the most dangerous and awe-inspiring public prank of all time. Dramatizing Petit’s story as a twisty suspense tale, Marsh directed a film that was as suspenseful and breathtaking as Petit’s walk, a picture so good that even the usually serious Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Science had to take notice, awarding it the best documentary Oscar.

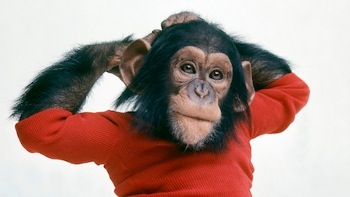

So, it should come as no surprise that documentary fans are eagerly anticipating Marsh’s follow-up, Project Nim, which is screening in Park City as part of the Doc Premiere section. Project Nim tells the story of Nim, a chimpanzee raised as a human child as part of a linguistic experiment. To learn more, I recently spoke to Marsh, who is currently putting the finishing touches on the film for Sundance.

Filmmaker: What attracted you to this story?

Marsh: The project started with a 2008 book that the producer of the film noticed. It was the story of this chimpanzee, who had been part of this famous language experiment in New York, where they were trying to figure out whether a chimpanzee could be taught language if he was raised as a human from birth.… The story has a lot of twists and turns, and that appealed [to me] on a really base level. It’s a great story, and I look for that. Also, because it’s a chimpanzee, you’re encountering ideas about evolution and communication and where it comes from. Within this great story, there are these big ideas, which we don’t belabor, but they are there to ponder if you wish.

Filmmaker: With Man On Wire, you had this great cinematic image – the wirewalker between the Twin Towers, but the concerns of Project Nim seem decidedly more earthbound and domestic. How did this affect your approach?

Marsh: Man On Wire is a breathtakingly simple story: it’s about someone doing something that’s impossible. Nim’s story is more complicated, so I’ve chosen to tell it linearly. It has a very simple structure because the story itself is quite complicated. Man On Wire offered itself as a genre film. This film, the imagery is much stranger and much more elliptical. The imagery is much more evocative and surreal.

Filmmaker: Was there any piece of archival footage that really triggered your imagination or influenced the overall visualization of the story?

Marsh: The archive was going to be the key to the visual imagery. Our chimpanzee never met another chimpanzee for the first five years of his life. He was taken from his mother and then was living with humans until he was five years old. There is some very moving footage of him meeting a chimpanzee. It’s wild, because if you think you’re a person, meeting a chimpanzee that looks like you is going to be very upsetting.

Filmmaker: Nim is a strange subject to profile, in that he’s not able to speak for himself.

Marsh: I haven’t quite seen anything like this before, a story focused on one animal throughout his life. A Bresson film, Au Hasard Balthazar, was a very big influence on me. It’s a film about a donkey who we watch as he moves around people’s lives. I found that film very revealing because it had the donkey passing through people. Project Nim is about the human behavior the chimpanzee activates around the people he meets. There’s a human drama around him.

Filmmaker: There’s always a human drama around animals, mainly because people anthropomorphize, project human thoughts and feelings, on them.

Marsh: That’s true of chimps in particular because they resemble us in behavior and appearance. We do have a temptation to project onto them emotions and feelings they really don’t have. The chimpanzee is very endearing in many respects, but he’s also very dangerous. We tried to create an accurate portrait rather than indulge in clichés. We tried to lay out exactly how he is and not make that too sugary sweet.

Filmmaker: Did you speak to any people from PETA or any other animal rights organizations about the issues surrounding keeping animals in captivity?

Marsh: The issues the film throws up are not campaigning, they’re just based on narrative. There are issues the film raises, but that wasn’t the point of the film. We didn’t start out to make a campaigning animal movie or some film that was going to deplore the state of films in captivity. We didn’t invite comment or opinion from animal rights types of people.

Filmmaker: This is your second film at Sundance. Can you talk a little about your first and how that shaped the way Man on Wire was released and received by the public?

Marsh: Man on Wire went to Sundance only three years ago. It wasn’t on anyone’s radar, and it premiered quite late. It was pretty much overlooked; I think I can say that now. It was discovered by people but it wasn’t by the people who came to buy films and haggle over them. That whole ballyhoo didn’t happen. It was picked up by a small distributor at the back of Sundance and was a very simple deal. The way it took off at Sundance was very old-fashioned, very kind of word of mouth.