Back to selection

Back to selection

Women Without Men’s Shirin Neshat

“It’s very flattering to be interviewed by a film magazine as opposed to an art publication,” said Shirin Neshat. “I am very flattered anybody would think it’s worth talking to me.” Widely-acknowledged as one of the most influential contemporary Middle-Eastern artists (and apparently one of the most modest), Neshat and her work are staples of museums and galleries around the world, while remaining relatively little-known in film circles. That changed this year when she burst onto the independent international film stage with her first feature film, Women Without Men. The narratives of four women in 1953 Iran are interwoven in the film, which was seven years in the making. Each character comes from a different background and social class; one by one they are drawn together in a mysterious, isolated garden outside of the city where they find solace, comfort, and family in one another, at least for a little while. Women Without Men won the Silver Lion for Neshat as Best Director at this year’s Venice Film Festival, and will make its American debut at Sundance this January.

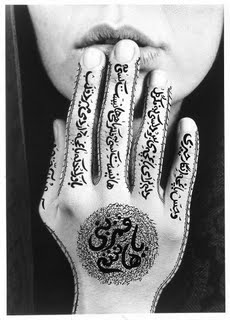

Forbidden to return to Iran, the country of her birth, Neshat studied at Berkeley and now lives in New York. Her multinational background is mirrored in the film: here, Casablanca stands in for Tehran (where she is not permitted to film); the producers hail from Europe, and, like the director, the actors are primarily Iranian emigrés. Dream logic and juxtaposition order Neshat’s video installations and photography, and this is also true of Women Without Men. Based on a slim, brilliant 1989 novella of the same name, the film’s tone differs from that of the book. They are companion pieces, like versions of the same song by different bands. Although both employ many of the same characters and surreal, magical story elements, the spare, unsentimental prose of the book, which is frequently interspersed with single lines of thought or dialogue, is very different from the serious, lush, and highly-stylized aesthetic that defines Neshat’s film. The evolution of her intense, ritualistic imagery can be traced back through previous work. Women of Allah, an arresting series of photographic portraits of women in black chadors holding guns, swords, and flowers–including Neshat herself–featured detailed Persian calligraphy filling in positive and negative photographic spaces. In 1996, Neshat turned her attention to video. Shooting on 35mm film that was then transferred to video, she has created 18 single and two-channel digital installations, many using dual or opposing projection. The pieces have names like Rapture (1999), Passage (2001), and Turbulent (1998), the latter a split screen singing competition between a man and a woman that transgresses against Iranian custom that prohibits women from singing in front of an audience of mixed genders. The piece won the International Award at the Venice Biennale International Golden Lion.

Women Without Men began its public life as a series of individual video pieces named after its main characters: Mahdokht (2004), Zarin (2005), Munis (2008), Faezah (2008), and Farokh Legha (2008). The videos were shown in darkened gallery rooms that alternated with brightly-lit spaces displaying large-format photographic still images. Landscapes featuring oceans, cities, gardens, streets and homes were depicted vividly along with the gazing, searching, characters who are simultaneously archetypal, symbolic, and individual. The characters evoked questions of desire, beauty, history, and ambition with their staring eyes and detailed settings, props, and costumes. For the artist, the pieces are emotional touchstones, visual bridges between motifs from Neshat’s homeland and America, her adoptive home. The perfect places to explore them are the movie theater and — of course — the film magazine.

Shirin Neshat: It’s so strange to finally wake up at your own house after much traveling—sometimes I wake up I don’t know what country I am in or what time it is. (Laughs) This morning I woke up and was in a state of zombie.

Filmmaker: Oh no!

Neshat: It’s so nice to wake up with your own apartment. I didn’t even leave much today. I’ve lived in so many horrible places that it feels good to finally be here. I think I paid my dues in New York. I’ve lived in every possible corner that was filthy or loud! [Laughs]

Filmmaker: Really? Your apartment here in Soho is just lovely… What was your worst New York apartment?

Neshat: I remember living in the East Village, several different locations, but once above a punk rock nightclub, and they were just always driving me crazy. That was on Avenue A and Second Street. Then I lived on Avenue B and 12th Street, where there were a lot of people up all night. Then I lived in Chinatown, on East Broadway. It was really—it’s dirty, like the hallway hadn’t been swept for like 10 years. And we had a methadone clinic next door. So getting out of the house with a baby and a stroller, and there were heroin addicts next door, and they were spitting—it was just disgusting. And then I lived in Brooklyn. And then I lived on Elizabeth Street and then in NoHo. Those were really nice, but temporary… And finally here.

Filmmaker: And now you’re home. Themes of home and family arise throughout the film; your female protagonists even seem to create a family of their own.

Neshat: Yes, a community. Their garden was meant to be a place of exile; a place that these women could escape to, away from their problems; a place to be temporarily at peace. A shelter, a place of security, a new beginning, a second chance — these ideas are very poignant for a lot of us who are displaced from Iran. When I was young, 17, I left my family and never completely had a family ever again. Every seven years or so I have moved to a whole new beginning, a whole new situation [where I] try to feel a sense of security. But I’ve been a nomad. I hope it doesn’t change again, but it seems I regularly move from place to place in a big way, make new relationships and communities, and then move on again. The idea of nomadic feeling, always looking for an idea of security, is very personal.

Filmmaker: Is it a surprise, if not a contradiction, to say that in exile, you have found a home?

Neshat: How can you go about creating a new safe, secure or comfortable environment? First thing that happens, you surround yourself by Iranian people. But I’m not really a typical Iranian either; I was so young when I left that I’m very international; so for me, it’s really about balancing inside and outside of the Iranian community. To this day, I feel disjointed going in and out of the Western community and the Iranian community. I try to belong to both, but I always feel slightly an outsider and I believe that for me, as for a lot of artists, subjects that are very important to them peek their way into their narratives, characters and concepts.

Filmmaker: How did you find the book that you adapted into this film? I look forward to reading it.

Neshat: It’s a very small one; you can read it in two, three hours. Though I don’t know if I should tell you to read the book. Which book have you ever read that has translated into film that you’ve liked? [Laughs] When I decided finally to think about making a feature film, I looked for the right story. It’s actually just what I’m doing now, for another film, which is really exciting. I was recommended a lot of books — like I am now — and scripts and stories to get inspired, and having worked with women’s poetry and having a feminist edge, a lot of people gave me novels to read by women. Shahrnoush Parsipour is one of the most important woman writers of modern literature from Iran, and I knew her writing as a young kid, a long time ago.

Hamid Dabashi, a friend and scholar at Columbia University, handed me the Farsi version of Women Without Men and said, “You should really read this.” All Shahrnoush’s literature is surrealistic, magic realism. She has this incredible imagination, and her writing is unlike other literature that I’ve read. It’s really Iranian, rooted in Persian poetry, mysticism, religion, politics and historical events in Iran. Yet at the same time, she has one foot in universal, ephemeral, timeless, existential, and philosophical issues. I realized that it was the right story for me because in my work, I’ve asked deep personal, philosophical questions as a person and as a woman. I’ve also engaged with larger issues that are above and beyond me, too.

Shahrnoush invented these characters according to some of her own mad ideas, and then I took them and I shaped them according to mine. This novel is set in the city of Tehran in the 1950s. It begins with very important historical events in the city, and then we come to the orchard, a completely different space. In my other work, these paradoxical elements were also really strong. Of course, I knew how difficult it was going to be to re-adapt a story that involves five protagonists and much historical material. But these were my initial and fundamental attractions: the book’s political and poetic properties.

Filmmaker: What spoke to you about the four central women characters?

Neshat: I think that the writer did a great job of choosing very interesting, diverse characters — socio-economically diverse as well as diverse in the type of dilemmas they have as women. Shahrnoush and I talked a lot about what childhood is like and how deep psychological issues of the body can be. As a first time feature director, it was interesting to think about how to develop their characters and think of them cinematically.

For example, Munis is interested in activism, social justice, issues that are larger than her personal needs and her own narcissistic life. Like her, part of me always wants to be involved in activism; really, really wants to get very angry; and wants to do something for others.

With Zarin, it’s a question of her obsession with the body and her feelings of shame. [In response to external] stigmas, taboos, and judgments, the woman self-punishes. I’ve always had problems with my body and so in a way, I’ve always embodied this. I physically get ill at times when I feel a lot of pressure, and have faced issues of anorexia, thinness, and the need to be desirable.

Even Farrokhlagha, the middle-aged character in her 50s, is thinking still about vanity and wanting to be beautiful and desirable, wanting to start over again and be a pioneer. This is something that I think is common in most cultures, though perhaps it is particularly [powerful] in my culture. Women hit 50 — it’s over, you know? In some ways, I embody her dilemma. They’re narcissistic things, yet very human. It’s really undeniable that all of us want to beat aging and be desirable and admired forever…and that it’s just not possible. [Laughs]

With Faezeh, the part I like and identify with most is this question of the security of tradition and traditional life; the security of wanting a simple life that involves raising a family and having a husband. That’s something I’ve never really had, you know. Everything for me has been kind of bohemian.

Filmmaker: Did you shoot primarily on location, or did you also use sets?

Neshat: We shot everything on location, just a little bit of the green screen, where we had to do when she had to fall. In Berlin we did that. But everything was shot in Morocco. We really didn’t have any money to do any sets elsewhere.

Filmmaker: Your 2007 New Yorker profile mentioned that you didn’t own a camera. You had your videos shot on 35mm and then transferred to video.

Neshat: Yes; I never even studied photography. I’ve always worked with a still photographer, or here, a cinematographer. I did not make the film alone. [Art is often] about finding ways of collaborating with people who can help,and in all the areas that you’re weak, to build more meat. I think the most important thing to mention is the collaborative part of this process. Shoja [Azari, my collaborator] and I worked forever on all the video installations we have done. When I chose to make this film, we co-wrote the script. Shoja has spent as much time on this project as I have and has shaped so much in the scenes. From the directing to the post-production, he’s been involved in every part of it, and has also helped me make this move from arts to film. I want to see that Shoja take the credit as much as me, because very often people see me. Now, he himself is about to shoot. His turn is coming now. He’s just turning his script into a film that I think he’s hoping to shoot in February. I’m supposed to be not in the driver’s seat, but in the passenger’s seat, to help him.

For me, [photography and cinematography] are about framing. Everything is carefully framed. In the feature film, everything was carefully framed and discussed in advance, almost drawn. We worked with a great Austrian cinematographer, Martin Gschlacht, who was unbelievably involved in the process. The brains of this project were Shoja, me and Martin. Every single shot was dissected both in terms of the dramatic process of the acting and also in terms of the framing. Later, he was very involved in the color correction with me. For me, the lighting is very important, and he’s a master of lighting.

With the bathhouse, for instance I really, really wanted a shot in a space that was a very high ceiling, like a dome from which we could pan down. I wanted to capture the bigness of the space. But to light such a space is really difficult. One earlier cinematographer said it was impossible. It was going to be completely sad to lose the space if you couldn’t light it, you know. I explained to him what I want, and the relationship of Zarin to these people. Martin said, “I can do it.”

I think my very favorite shot of the film is when Zarin is on the ground, on the floor, and she’s completely nude and she’s just sitting like this, this naked body. Do you remember when the boy is looking at her? When we had these little boys there, it just seemed incredibly poignant to have this moment; it’s like a loss of innocence. She was so out of it. But for a little boy, to be confronted with a nude body in this condition is just devastating. I thought that was a very important shot.

Filmmaker: How would you describe her condition?

Neshat: She’s anorexic. I mean, there’s no doubt about it. And that’s the actress — the point was not just that she was bleeding, but she was just bones. She was no longer an object of desire but an object of pain. For this little boy to see a naked body — because the other women more or less were covered — but to see it in this condition, it’s pretty early to be exposed to such a torturous figure. When Zarin goes to the mosque and all the men are down, or when she’s floating in the water, these things were treated like still photographs. With Martin, we discussed the images very often like that.

But because of the script, we also had to think about how we were going to edit. We had a continuity person, which was new for me. Now I had to think about in relation to the other, next shot and next shot and next shot. In the art installations anything could go, and then later you’ll deal with it in the editing room. But here, no. You cannot go from A to C without going to B, and point of view is important, and this and that. This was an incredible lesson. We could approach it somewhat artistically, but we always had to keep in mind the story development.

Filmmaker: Was it a process that you enjoyed, being in a new place and learning so much so quickly, or was it frustrating?

Neshat: It’s always really exciting to learn a new language. You’re seduced by education, and ask yourself, “Could I be good at this? Could I really?” It tests your ability to tell the story using very different logic. It’s very flattering to be interviewed by a film magazine as opposed to an art publication, you know. Also, as an artist, I tend to repeat things, and when you get good at something, it really takes a lot to stop repeating yourself. I kept wanting to write on my photographs, for instance, and when I made videos I kept thinking of double projecting. Yet sometimes you just have to boldly go against your own patterns. It can be liberating to suddenly find you’ve reinvented yourself.

This is the most exciting part of cinema for me: I’m just a beginner, yet it’s such a complete form that I don’t have to drop all my tools. I don’t have to stop thinking photographically. I don’t have to stop thinking about a choreographic way of telling a story. I can keep all of it, it’s just that now I have to tell a story and I have to keep my audience for a very different time span. The attention span of a person in a movie theater for 90 minutes, it’s really different than a 10-minute video. It’s a challenge that I love.

Shoja was asking me yesterday if I would want to continue with magic realism [in film], and I thought, “No, I don’t think so.” Most of my past work has been surrealistic one way or another, but I think it’s the strangeness more than surrealism itself that I need to keep and maintain.

Filmmaker: Could you talk about the shot where characters go through the wall and follows the little stream that goes through the rushes? It’s beautiful, and haunts me in kind of an Alice in Wonderland way, the entrance to a secret land.

Neshat: It’s also very sexual, like you’re entering a hole. That hole became a bridge between reality and magic, between the world of the orchard and the external world of 1953. Time had stopped. When Farrokhlagha and Faezeh and Zarin came in, they felt foreboding but were attracted to the garden. Faezeh was terrified.

I found it poignant to think that beyond this wall there is a mysterious world that doesn’t belong to anywhere else, and that once you’re there you can be so safe. It’s a very allegorical idea. There’s no mist outside, but as soon as you go in, it’s full of mist. This is why we also made it silent with just natural sounds because we thought even the garden had a voice of its own. When each woman comes in, there’s a repetition of a certain type of birds or a certain type of sounds and you say, “Ah! This must be the same place.”

Also, the pacing of the film became slower once we got there, and the camera was much slower in panning around the trees. It was gentler, like the place had its own logic. It was haunting but also beautiful, and very different than when you were in the city and there was more action, it was more real, and it was faster. The other thing was that geographically, it was not consistent. There was a desert, and then there was this lush green. It was like the garden had no walls once they entered. So again, we were really playing with these paradoxical spaces; like heaven or like hell, but nothing that belonged to the earth. Maybe it was when Munis died, that was life after death; or maybe this is a place where all the women are dead. Until the army of guests comes in to the garden, which is like a rape. When Farrokhlagha decides to open it up to the people, things start crumbling down. The garden is betrayed by being opened to the outsiders, you know.

When the film was first shown, immediately some people accused me, saying, “She’s just making these images because they’re so controversial and sensational; she’s sensationalizing violence.” The Iranian people did this also; as much as they liked it, because it looked somehow interesting to them, they were always kind of endorsing but also criticizing. When I really think about this film — this is a very important thing to add to this interview — it’s really kind of a manifestation of classic Persian literature into visual imagery. A lot of metaphors that are really rooted in our mystical tradition of literature are very subversive, poetic, existential, and philosophical.

As Iranians, we think these things are understood by everyone, but they really are not, you know. For Iranian people, for instance, the garden is the most important metaphor; in Persian painting, literature, and poetry, it’s a place of spiritual transcendence, a place of freedom. A lot of information gets lost when even the style of the film, its poetic nature, can be so alien to the Westerners that it may be read as too melodramatic, or not contemporary enough. But at the same time, the conceptual approach of the film — because I have been educated here — could put off other people who are non-Western and don’t understand this kind of construction of stories.

Filmmaker: How did you approach the detailed re-creation of a specific time period?

Neshat: The novel takes place in the summer 1953, a very interesting time. What happened politically in Iran then is not discussed very often anymore, and is often overlooked now that we’re talking about Iranian and American tension. Most Westerners still think of Iran during post-Iranian Revolution era, when Iran had become a completely different type of society. I wanted to show Iran when it had a different look, and remind us Iranians what we were like as a community, as a society.

Politically speaking, the United States and the British had everything to do with the overthrow of the democratic government and Prime Minister Mossadegh. This paved the path for the Islamic Revolution. Had it not been for that coup, his overthrow, and the return of the Shah, we would not have had a slow breakdown. Antagonism toward the West, particularly America, developed during this time. When the Shah came back as a dictator and began to kill a lot of people, people hated him and eventually embraced Islam as the next authentic ideology, an anti-West. We often get categorized as this fanatic and barbaric people, but if you look at the history, actually the U.S. was quite barbaric in the way that they intervened in another country’s affairs.

In this film, as you saw, history is not really treated in a documentary or didactic way, but the film does try to point toward the feeling of betrayal and defeat that people felt — and this is something that happened again this year. We were not able to access Iran in any way, and we were limited to working in Morocco — this was a real issue. It was a very international project — sometimes this was an asset and sometimes a problem. Shoja and I have been going across the Atlantic god knows how often; physically and emotionally it was really a test of my endurance. Yet it was very interesting for us to look in that time and see how people looked, how people dressed, and how the Muslims and the Westernerized people coexisted. It was just like a very interesting tapestry, a complex and diverse society, though now it’s homogeneous because of this regime. We went out there researching the architecture, the costume, the hair, and the different political and cultural communities that existed. It was fascinating.

For example, when we looked at the images of Tehran in the 1950s, it’s all these Art Deco buildings and looked like the beginning of modernity. If you look at Russia, or Casablanca, as we did, we started to pinpoint some of the buildings that really [resemble those in] the books of old Tehran.

From Iran, we found books. Footage usually came from the BBC. The political images from the coup d’etat came from a documentary made, ironically, by BBC, which basically glorified the coup as if Mossadegh was an evil man and had been overthrown. But if you looked at an intellectual, artistic community, like the world of the older woman, Farrokhlagha, you see her friends and the café and all these artists. You see the kind of discussions they would have; they’re very well-read of both Western authors and local Iranian authors. You see that they’re well dressed, and they also talk about politics. Then, you also have the fanatics, backwards and oppressive and religious in their way of thinking. Then, you have pro-Shah people like Sadri, the husband of Farrokhlagha, who were not really intellectual but lovers of monarchy leadership. Then, you have the communists, the white-shirted people. In our research, we read a lot of books with historical explanations about the coup. You get a different explanation from each camp.

Shoja and I interviewed ex-communists who had fled Iran for Berlin after the Shah came back. We also talked to the people who were pro-Mossadegh and pro-Shah to get an idea of what that was like. It’s very, very interesting, the dynamics of that time. You might like the great book All the Shah’s Men by Stephen Kinzer; it’s like a thriller that describes the chain of events that led to the coup. We did our best to become informed about the historical, political, and cultural life of that time. Then, we had to fictionalize everything, to make sure we are close as possible to the truth but within fiction, not documentary.

We also had a limited budget. Really we worked under 4 million Euros, so we had that in mind. We had the street protests, with a massive amount of cast where we blocked off city streets. We had to go to the orchard and have a whole thing there. The four women each had a very different lifestyle—they had to dress a certain way; live in a certain kind of location. For example, since Zarin was a prostitute, we studied the brothels at that time. There was a city for prostitutes; all during the monarchy, people could actually go to that city.

Or, for another example, we also had to look at the traditional architecture of Iran where the middle class lived, like Faezeh and Munis. It’s Persian architecture the way that they each have a little pool.

Filmmaker: In the courtyard?

Neshat: Yes, so we actually built the little pools. It wasn’t like that. All the flowers, all the landscaping was by us. It was as close as we could get to Tehran in the ’50s. At locations like the bathhouse, which for me, is very important, we built all of that. It was actually a public bathhouse, but the pool you see was created by us. The dome was there, but the space was empty.

It was a public bathhouse in Marrakech. We dressed it to be like a Turkish-Iranian bath. I think we did a great job, but even if it doesn’t seem exactly like Iran, I think the fact that it was nomadically done added flavor. It’s the license of an artist who’s herself in a kind of exile. I could be making a film that it’s Iranian, but it looks Cuba and Morocco and In the Mood for Love. This is a very global time. I have often used of color that was not necessarily authentically Iranian, but as an artist I took the liberty. It is like symbolic of what the time was like.

Filmmaker: I recognized several scenes, images and costumes from your video installations and photography in the film.

Neshat: Yes, we basically used the same footage. To dress Farrokhlagha and Faezeh and Munis, for me, was really difficult. It was out of my element. I had to really think about their personalities, their time, and the actresses, and really dissected the characters. With the dress for Faezeh, it was about her innocence. When I saw that dress, it just radiated that kind of girlishness. With Munis, we were talking about a more boyish, nerdish girl; the kind who studies a lot, but is not really pretty to look at. She is always like proper, like a little doll with her haircut and those little shoes. [Laughs] It was intentionally designed for characterizing who she is. With Zarin, though beautiful, she was so skinny it was hard to make her really desirable.

We worked a lot with secondhand clothes, you know — except with Farrokhlagha, who was the most elegant. Our costume designer’s from Austria, and he did actually make the clothes for Farrokhlagha. But the worst thing happened was that we originally had an actress from Iran who was supposed to play the role. She came, he measured her, we made all the dresses, and then she couldn’t play in the film! Suddenly we had to make this dress work for the next actress. That person had gained some weight since I had last seen her, so it was like, “How are we going to fit?” Do you remember that gray dress with white polka dots? It was bursting, actually! Yet in a way, the fact that she was a little bit voluptuous and heavy, I really felt it was good.

Almost everything didn’t fit her. The costume designer had to leave and we still didn’t have a dress for the party in the orchard. They had brought a whole trunk of clothes to Morocco from Austria, and here I was with her going through all the dresses. We were panicking because the shot of the party was the next day and we still hadn’t found a dress for the main hostess of the party! Luckily we found that dress at last. A lot of it was well planned, a lot of it was improvised, you know.

Filmmaker: It’s a wonderful scene, and one in which clothing adds so much. How do you balance planning and improvisation in your artwork?

Neshat: Here, the planning and organization were intense. We started this project in 2003, and then the script wasn’t finalized until 2007. Then we shot the film in eight weeks, and edited for two years. We spent a lot of time of going back and forth about the script, preproduction, production, and postproduction. The video installations were also very well organized, but they were small projects. They were maximum 10 days of shooting and a much smaller crew. Here, we had like 60, 80 people in all different departments, plus a casting agent. I never have had a big costume department or hair and makeup; usually I have one person who is like all that. But this was kind of an epic period film. A producer was German, and the co-production office was French and Austrian and mainly German. The music and even the actual shooting of it — there were so many people involved. Shoja and I spent about four months in Morocco and broke down the script into a shot list. Everything was really organized.

Filmmaker: Has your previous work been more intuitive?

Neshat: This time we had a script that had to be approved by the producers, and they had to get funding based on that, which was different. Also, I’ve worked only a little with professional actors, so this was really very different. But in the past we always storyboarded everything. When you storyboard, and especially if there’s not so much dialogue and continuity, there is a lot of flexibility. You can come to the editing and put the puzzle together all different ways.

In the editing, we just threw away the script and completely restructured the film. All the main shots were there, but it wasn’t really working the way we had written it. This is why also it took us a long time: we gave ourselves the liberty of reorganizing the film in the editing room. It’s a plot-oriented film, and there was always this risk of being either overly conventional and narrative, or overly aesthetic and not narrative enough. We dissected the balance between the visual imagery and the story, and I tried to make the best balance in my judgment. Yet I knew that this story itself would never allow a completely conventional narrative. It is a strange story, and so it is a strange film — you cannot make it an un-strange film. It’s impossible. That’s exactly why I chose it.

When I think about all my past works, in photography and video, there’s always something strange about them, and that strangeness is what I like. That strangeness makes many people not like it because they don’t relate to it; while some people like it because of that quality. But then the question: how do you come in and out of the magic elements in the story? We were so afraid of making a film that was like Halloween or something — like when the woman comes out of the grave or the faceless thing. We didn’t have the Hollywood money to make these perfect special effects. From the beginning we decided that we’d do the Buñuel style: first you see it, then you don’t see it. When you come to magic, it’s not like you savor it and dwell on it. Instead, you’re telling a very realistic story and suddenly someone comes out of the grave. This balance between the art and cinema, narrative versus non-narrative, strange versus non-strange, and reality versus surrealism is fundamental to the way that this story tries to tell itself.

We knew this was a very difficult story to make, to sell… (Laughs) and to become popular because it really is a demanding film for people. We tried to put in beautiful music, beautiful images, beautiful colors, and humor, but what they get out of the film is just like an artwork. It’s a very conceptual art piece. It was an experiment, an experiment that has a lot of flaws because it was an ambitious experiment, you know. It tried to be philosophical, historical and political. It tried to be poetic, realistic, and magical. It dealt with individual women and the whole community of Iranians, all looking for freedom and change. The audience had to try to get layers of meaning and symbolism and metaphor. How to do fairness and follow four protagonists simultaneously, not making one more important than the other, and give the country of Iran almost like it’s another character, a fifth woman? Everybody said, “Are you sure for the first film you want to make you want to be this ambitious? Historical periods, four characters, magic realism—you’re aiming for disaster.” But I loved the story so much, you know. You give it the best, and you accept its own logic.

Filmmaker: I love the music, and wonder if you would discuss its place in the movie?

Neshat: The [Ryûichi] Sakamoto music and the Persian music that people were singing? I wish Sakamoto could hear you because, to be honest, we had a lot more music, but we at some point felt that that was a bit dangerous. You know how sometimes music can be kind of manipulative of the story, of your emotions? We felt that less is more; that the music should add to the emotions of the film but not really take total control. So we brought a lot of silence.

Ryûichi Sakamoto and I met a few years ago. We always wanted to work together, and we were looking for the right project. I’ve always loved his work; like when I heard the music for The Last Emperor (1987) and The Little Buddha (1993). He’s also so diverse in the way he does things, and I love the way he incorporates indigenous music of the countries where the films are shot with his own music. He has brought Indian music into his own music, and in The Sheltering Sky (1990) he brought Arabic music into his own. This film tries to be universal and timeless and Iranian, so he incorporated some of the Persian music into his. At the end credits, he incorporated the beautiful santour music from Persia with his own. I feel like the amount of music that’s there really works, and when it comes, it’s really powerful.

Filmmaker: You mentioned that you had a limited budget for what you wanted to do. Did that encourage you and your team to be creative in ways you wouldn’t otherwise have been?

Neshat: We struggled a lot financially. In many ways, this was a very humbling experience. We’ve never worked with huge budgets, but in this case it was very difficult to raise the money. This project was a labor of love for anyone who worked on it; everyone worked unbelievably hard and didn’t get paid enough. Many times, the project would have been at risk if it didn’t get enough money. But somehow we pulled it together. When I think about this project I think about struggle and I think about being a student. I think about how hard we worked and how grateful we are that we finished it and had some acknowledgment.

We’ve gotten rejected by funders; and once, when we were about to go into production and were already on location, a funder backed out — there were numerous times where there was very great risk and good enough reason for the project to dissolve, but we didn’t give up. It was also very hard for the producers, who had never worked on a period film like this or with Iranians like us — and in a language they don’t understand! It was challenging in every single dimension. There was nothing that didn’t not go wrong. [Laughs]

When you’ve devoted yourself, you make it work somehow. Yet when we went to Venice and we felt so irrelevant in this big festival. We were saying, “At least we were in competition. Goodbye!” We got in the airplane and came to [the] Toronto [International Film Festival] with Shahrnoush. We arrived at night, slept, had the screening at noon, and then as soon as we got out, like 2 o’clock, the phone rang from Venice, from Marco Müller, asking us to come back immediately [to accept the Silver Lion award for Best Director and the UNICEF Award]. [Laughs] We were actually there less than 24 hours! But it was so exciting.

Filmmaker: Speaking of producers, Barbara Gladstone has been your gallerist for many years, is that right?

Neshat: Yes. Barbara has basically been the producer of the video installations. She was in this one just for a small amount, because I made those video installations [with some overlapping material]. But for the feature film she was not really involved in any direct way. The difference, I think, between an art gallery dealer and a producer is that with Barbara, she doesn’t even usually ask, “What is your idea?” Of course, [the means for my video installations are] very limited. It’s not a huge amount of money — maybe $100,000 or $200,000 maximum. But I wouldn’t even write anything down. I would say, “I’m going to make a project,” and normally I would prepare a budget, and she would give me what I needed.

She trusted you and hoped that you would do something good — both artistically and that she could sell. I really admire that element of risk that came from the gallery as funder. The difference with the producers was that they absolutely needed a good script. No funder would fund it based on anybody’s name. It was also much more of a collaboration; producers had to contractually approve the script and the final edit. Maybe because it was also my first-time film, they were very careful about what’s going to come out of this. Although most of the money doesn’t come directly from them, they had to report to funders, and these are relationships that they have to maintain, so it just cannot be a disaster. At the same time, they are taking a risk by working with me, which I really respect, because I have no record of this.

When we worked on the script, we had to meet endlessly with the producers. I worked with a script consultant in Berlin — I literally moved to Berlin for part of this process —to really make sure that they were happy with what we were doing. When we shot the film, they did a lot of test screenings everywhere in Europe to get feedback and make sure that things were being addressed. But at some point toward the end, I felt that I really needed to have them back out a little. I mean, okay, it’s my first film, but at the same time there was a danger that there were too many cooks involved, and that this film would suffer from that. So I asked them to let me take the command of the way that I think it should be as a work by me. And so they backed out.

At the end, what is out there is really a projection of what I wanted as well as really listening to people and their criticisms. Shoja, of course, was a major, part of the construction of the story and this whole development in the editing process. We always had differences, but I think it was good. He tried to challenge me from the cinematic point of view. I also always tried not to forget the artistic point of view while still taking that leap. You’re much more free in the art world. But at the same time, you have a limited audience. The video becomes a commodity, so it cannot get distributed. You hope that it will have exhibitions, and the collectors — if anybody buys it — could share it with the public. But very often it’s almost impossible to even have it on the Internet.

With film, it’s an industry, but you’re not as free. You have to deal with the producers, distributors, festivals, and critics that are going to determine whether people should buy tickets or not. But at the same time, it’s not a commodity the way artwork is. It’s closer to the general public. This is one of the main reasons of my attraction to cinema. I love going to the movies, and I love the fact that I could make a film that could be visited by the average public as opposed to just exclusive art-world people. I respect them a lot, but I wanted to see if I could expand the audience.

On that note, I am still a strong believer that it’s possible to bring art closer to the people, and that you don’t always have to draw this line. Why can’t the general audience also see films layered and loaded with symbolism and meaning, that are beautiful, entertaining, have good music, and are a bit challenging? At the same time, there can be a narrative to follow and think about after they leave. Even Iranian people who are not really used to independent films could possibly relate to this film. They see their own history as well as the music and culture of their country, and they follow the story. I think this is the direction I want to go. How can you blur the boundary between visual art and the language of cinema, yet have it accessible to the general public?

Filmmaker: The film reminds me, in some ways, not only of Buñuel’s films but also of Maya Deren’s work.

Neshat: Oh yes; I love her work. It’s like a dream, her work. I was thinking of her yesterday — that when she made those works at that time, it must have been so difficult for people to relate to. Shahrnoush Parsipour explains her interest in magic realism by saying that so many hours a day you are sleeping, and so many hours you are awake, so your dreams are just as valid as the time you are awake. Why are we in denial of our dreams? With Maya Deren — oh my God, it’s to die for.

Filmmaker: I love her circularity, which seems relevant to Women Without Men. Also, watching your film, I was reminded at times of the films of Matthew Barney (also represented by the Gladstone Gallery), which make and reinforce their own mythology. Places become significant through elements of repetition, and the art that is ultimately sold is an artifact of the production of its making. Is that related to what you are doing here?

Neshat: It is, and that is also the way I think of his work. It has its own sense of mythology that you may enter it or not, and just enjoy the sheer beauty and enigma of what he creates. Sometimes it can be frustrating, but that’s the degree that he chose to go to. I chose to go less than that. For me it was the question of being between Julian Schnabel, Steve McQueen, and Matthew Barney. Not as conventional as Julian Schnabel, which is pretty much a straight feature film, or Steve McQueen (as they both have made fantastic films). With Matthew Barney, it’s dense to the point where it’s difficult to follow the narrative and sometimes you make up your own narrative. I really didn’t want to be that enigmatic; that’s his choice, and this is my choice. As my first exercise, I also didn’t want to make a film that was not me, or that departed [from my work] to the degree that people won’t recognize my own signature. Could I transport my visual vocabulary, the way I use choreography, and the way I use the camera into a narrative film? It was about the fusion of cinematic language and my art. I was also worried about the question of making an extended video installation, and I didn’t want that.

Some of the other characters were very worldly and down-to-earth, yet each is a myth on their own. Munis, for instance, is this very magical person and becomes this symbol of the Iranian struggle for democracy. She becomes like Jeanne d’Arc; she becomes the notion of sacrifice. Zarin herself is a type of sacrifice; she’s very saintly, very sacred, and she in a way reminds us of Mary Magdalene with Jesus Christ at the garden. There are all these kind of things playing underneath — some people might get them, some people won’t, but they were in our minds. Whether it’s my photographs, or the videos, or this film, they’re asking for trouble, because of the blending of East and West languages and approaches.

Filmmaker: Do you see yourself as a troublemaker?

Neshat: I think that there’s no real hope for it to be completely understood by one or the other. There will be always loss in translation. I would call this an accented cinema; it’s accented for the Iranians and it’s accented for the Westerners. It’s the same as I am sitting here, I’m dressed with this from here, and this from there, and this from Laos… [Laughs] We are like this kind of multi-influenced pollution of all these influences that it’s not so easy to pinpoint. In a way I wish I was just Schnabel. [Laughs] I was just like from one culture. But it’s impossible, because I’m really caught in between the two, and sometimes they’re a mismatch. The central style of the film, the energy of the film, is this meeting of the ancient and new, the East and West.

Filmmaker: Well, I’m glad that you’re not Schnabel. One is probably enough. [Laughs]

Neshat: Although he makes really good films. Do you see this film, Women Without Men, with an audience in this country? We did pretty well in Europe, but the producer, who is European, thinks that in the U.S. there is no appreciation for this kind of work. I know some people also really hate it. This was the most ambitious thing I’ve ever done, but I have to say that I found it satisfying. We managed to finish it, but there were many, many times that I just wasn’t sure if it was really ever going to come out into the world. Now that it’s starting to get some reaction, I understand that the reaction is very mixed, and remind myself that that’s always been the case with anything I did. Every time you finish a project, there comes a time when you read criticism. You get really discouraged or you feel like a lot of insecurity, and then you realize that that’s exactly what has been happening all along, and you’re still there.