Back to selection

Back to selection

SURVEYING THE DOCS AT TRIBECA

Attempting to wrap your mind around a film festival’s totality is an exercise of dubious value. Still, the dubious can be exceedingly difficult to resist. It seems to me that the documentary films at the Tribeca Film Festival are of a consistently higher quality than the narratives. But what doc rat doesn’t believe this at every festival? Still, there are extremely few stinker docs at Tribeca, and forget the bombs. After the screenings the descriptive word that I hear the most from the audience members is “good,” occasionally “outstanding,” but never “bad.” Stinker docs need not apply.

The universal need to know who we are, to know who we came from, is the theme of Donor Unknown (pictured above). JoEllen Marsh, a teenager from Erie, Pennsylvania, uses the Internet and the Donor Sibling Registry website to coalesce some 20 or so teenagers and twenty-somethings who are the biological offspring of Donor 150 at the California Cryobank in Los Angles.

Donor 150, Jeffrey Harrison, is certainly a character. A deeply spiritual hippie now in his fifties, he is an intense animal lover and all around eccentric who lives in a RV in a parking lot in Venice Beach. Will the boys and girls go to California to meet their biological father? What will they think of him? Will lasting relationships be formed?

Donor Unknown is a delightful documentary that informs — revealing how the kids and their mothers and, of course, Donor 150 feels about this strange situation, and even how the sperm donor process operates — while also being emotionally charged. After all, knowing your biological roots is rather primal. Director Jerry Rothwell and his small crew have crafted a stupendous film about a very unusual, yet becoming more usual, sort-of-a family.

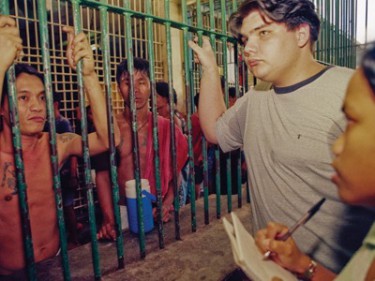

How can a young man, 19-year-old Filipino Paco Larranage, be arrested for rape and murder and convicted by a judge and the conviction upheld by the Supreme Court when there are 42 reliable witnesses who wanted to testify that Paco Larrange was partying 375 miles away from the scene of the crime? They even have photographs of Paco to back up their claim. How is this verdict possible? As they say in the Philippines, No problema!

First a media circus lays the frenzied groundwork and the populace gets cranked up for revenge. Old-fashioned racism and a powerful drug lord grease the wheels of irrationality. A phony witness suddenly appears. Presto! An endemic corrupt police force and an endemic corrupt judicial system deliver the guilty verdict. No problema!

Give Up Tomorrow tightly weaves this Kafkaesque tale to create a devastating indictment against a South East Asian nation that in the middle of the 20th century was called the bright star of the East. Although not a perfect documentary — mostly I would have liked to know more about the others charged with the crime — directors Michael Collins and Marty Syjuco have courageously placed an intense spotlight on a fiasco of a legal case that has roots in the corruption that runs deep into the social fabric of the Philippines. And for 13 years Paco Larranage has been languishing in prison.

Many documentary features should be reduced to shorts, yet few short films should be lengthened to features. Yet, at 23 minutes Incident In New Baghdad does not have enough time to say everything it should say. It needs more context, more sources, more conflicting viewpoints, and more story. Still, even at 23 minutes Incident In New Baghdad is one powerful and disturbing film.

The documentary recounts an attack in July 2007 when U.S. Army helicopters fired on a group of Iraqis, some armed with RPGs and AK-47 rifles, others unarmed. The casualties included two Reuters journalists and two small children. The media reported that a total of eight Iraqis were killed.

Incident In New Baghdad’s central character, Ethan McCord, a U.S. soldier, arrived immediately after the aerial assault and witnessed the carnage. McCord’s voice in the film is credible, haunting, and moral as he ends with a plea for Americans to take responsibility for their government’s actions.

Director James Spione interweaves McCord’s uncomfortable testimony with his gruesome photographs of the slaughtered and the U.S. helicopters’ disturbing video (released by WikiLeaks). There is news footage of several talking heads, one a retired general turned media analysis saying, “War is a terrible business.” A pitifully inadequate, callous remark after such a horrific incident, which is exactly why we need honest films like Incident In New Baghdad.

Documentary films take us far away to reveal what we did not know while other documentaries return us home to confront what we already know. Our School does both.

The Europe Community ordered Romania to desegregate its school system and integrate the children of its long discriminated against Roma (Gypsy) minority. Directed by two Romanians — Mona Nicoara and Miruna Coca-Cozma — this documentary focuses on the village of Targu-Lapus, and over a four -year period, follows three Roma children.

The integration plan is implemented and we see a strong undercurrent of Romanian prejudice, an occasional display of tenderness, with both Roma and Romanian children being just children — funny, playful, smart in a natural way — while some Romanian children imitate the prejudice of their parents. At the film’s end comes a strange twist, showing just how deep the roots of prejudice run. This should not surprise Americans.

Our School demonstrates that the reasons and goals of racial prejudice and discrimination are similar all over the world. Targu-Lapus is far off in the Transylvania Mountains, yet it mirrors what we know about small towns in the Appalachian Mountains. It seems only beauty has diversity; the ugly is the same everywhere — although at the end of this fine documentary, the Romanian community leaders are quite creative in embracing desegregation to perpetuate segregation. Logic has no meaning for those fired by hate and prejudice. Our School is a gentle and smart film.

Just when I had grown confident that I had the totality of the Tribeca Film festival in my cerebral palm — the docs are good, a few are great, hardly any, maybe none, are bad — came a celluloid mind bomb. I don’t mean the film was bad (although some will certainly believe so). I mean it detonated my little mental box that had wrapped Tribeca into a few simple phrases. You know, that totality stuff. On the other hand, a film festival that doesn’t get around to rattling your settled mind and uprooting your firmly held convictions isn’t much of a film festival.

Bombay Beach delivers a relentless array of characters — well, if you can call the down-and-out, impoverished people who carved a skid row out of the desert, characters. Halfway through the film, I wondered if it was worse to begin your life in this sandy ghetto as the children have or to end your life there as a legion of elders is doing daily. I decided that was not a question worth pursuing.

This film has no story beyond snap-shots, no context except a black present, and no history of anything. This led me to question if this is actually a documentary. It’s impossible to know what is staged and what is not, although I’m not sure that really matters since all of Bombay Beach is a weird stage. I do know the film is an episodic assault of moving images with sputtering yet understandable sounds often accompanied by beautiful vistas. As for message, maybe it’s the American Dream is dead. Or maybe it’s that human minefields are interesting. Or maybe it’s life is one mixed bizarre bag. By the way, if anyone had suggested I leave before the film ended, I would have shot them. Well, if I was packing.

When the film ended and I watched the audience carry their brains out of the theater, I noticed most had a strange glow of glee in their eyes. I don’t know what that was about. You’ll have to see Bombay Beach for yourself.