Back to selection

Back to selection

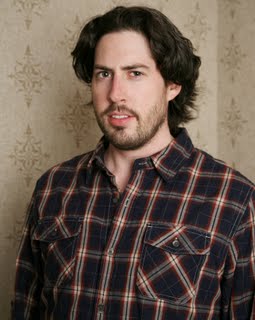

IF ON A WINTER’S NIGHT A TRAVELER: JASON REITMAN’S UP IN THE AIR |

By Scott Macaulay

Leading up to the Oscars on March 7, we will be highlighting the nominated films that have appeared in the magazine or on the Website in the last year. Scott Macaulay interviewed Up in the Air co-writer-director Jason Reitman for our Fall 2009 issue. Up in the Air is nominated for Best Picture, Best Director (Reitman), Best Actor (George Clooney), Best Supporting Actress (Vera Farmiga and Anna Kendrick) and Best Adapted Screenplay (Jason Reitman and Sheldon Turner).

Jason Reitman’s Up in the Air, which debuted at Telluride and went on to critical acclaim at Toronto, is a perfect film to watch at a film festival. It stars George Clooney as Ryan Bingham, a frequent-flying corporate downsizer whose Zen of life consists of collecting miles, amassing perks at his favorite hotel chains, crashing parties with great hors d’oeuvres spreads, and the serendipities of chance, no-commitment hookups. Indeed, one colleague said to me at Toronto after seeing the film, “I don’t know whether I liked the film because it’s a good film or because I think I’m that guy.”

But if the above makes Up in the Air sound like a light-hearted boomer comedy, a Wedding Crashers of the skies, that’s far from the case. Bingham’s job as he jets from city to city is to fire people. Lots of people. He’s brought in to do mass layoffs, and while his smooth talk applies a psychological salve to the destroyed egos of the suddenly unemployed, neither Bingham nor Reitman are under any pretenses that it’s anything more than a temporary Band-Aid intended to keep them from falling part before they leave the room. One of the astonishing things about Up in the Air is the clear eye it casts on 2009 America and a workforce undergoing the shock treatment of recession, outsourcing and the creative destruction of so many of our traditional industries. Reitman cast real fired workers in his film and what might have become a casting stunt is quite the opposite: Their voices are honest ones that humanize the employment indices that scroll along the bottom of our flat screens.

Up in the Air’s story takes off with a clever irony: Business-school grad Natalie (Anna Kendrick) proposes modernizing the layoff consulting business by doing the firings by iChat, a move that would destroy Ryan’s carefully constructed way of life. Ryan fights back, convincing his boss (played by Jason Bateman) that Natalie accompany him on a national tour in which she’ll learn just how difficult and necessary his face-to-face job counseling is. Stuff happens, including a relationship with a sexy businesswoman (Vera Farmiga) who would seem to be Clooney’s ideal match. (She and Natalie become a kind of ready-made wife and daughter for Ryan.) Of course, the film winds up juxtaposing the enduring value of family against the unexpectedly fragile identity provided by our jobs, but even here Reitman refuses to go for stock Hollywood uplift with a last line and image that’s among the most resonant cinematic closers I can remember.

Choosing after the enormous success of Juno to return to a project he actually intended to be his first feature, Reitman has made a skillfully executed, wonderfully acted relationship drama for our times that also happens to be, yes, a Hollywood movie. His is not a Barbara Kopple or Laurent Cantet film. He knows how to nail big plot points, create slickly inviting music-driven montages, and how to make the most of a movie star in a lead. (At times the movie reminded me of Jerry Maguire, but with “You had me at hello” replaced by “You’re a parenthesis.”) But with this film Reitman confirms that he’s also become a real master of tone and of portraying relationships and ideas honestly within commercial cinema, which makes him part of a tradition of dramatists and social satirists who are just as endangered in the studio corridors as independents are at the multiplex. I spoke to Reitman just a few days after Toronto, where critics dubbed his film an instant Oscar contender.

Paramount Pictures will open the film in November.

Filmmaker: So, I was trying to figure out why I loved your movie…

Reitman: Because you work in an industry where everyone’s losing their jobs and the entire business is going under?

Filmmaker: Well, there’s that. [both laugh] But it took me a day to remember a sociology paper I wrote while as a student at Columbia about the sociology of the business traveler. My professor had suggested that I apply for a Fulbright and expand it into a book, and I had this vague fantasy that I’d spend a year after school traveling the country staying in one hotel after another. So I’d have basically been that guy in your movie, except I think my enjoyment of the experience would have been an ironic one.

Reitman: Oh, but he loves it.

Filmmaker: I would’ve loved it, but in a different kind of way.

Retiman: I kind of sincerely love it. I think that’s the reason why I like the book.

Filmmaker: Yeah?

Reitman: I’m an obsessive traveler. I love being in particular airports, and I love that I know how to navigate them very well, and I love being in hotels. I love collecting miles.

Filmmaker: What’s your favorite airport?

Reitman: I really love Denver, which I think is just fantastic. There’s this one terminal that has a long run with four moving walkways going one after the other until the end. And at the other end are these giant glass windows that look over either tarmac. And, specifically, there are red destination boards at each gate. It’s just so open. You slowly pass one destination after another, and you truly feel this idea of, “If I stop here, I can just go there.” And you really can go anywhere. It’s not connected to the main terminal — you have to take a tram to get to it. So when you land there and you fly out of there, there’s also this kind of separation: You’re on an island. You’re not connected to the world. You are in this hub in the middle of the Earth. They built the Denver airport purposefully further away from the city.

Filmmaker: This is the new one, the one that had all the controversy around its construction?

Reitman: Yes, exactly. They built this road to the airport, which was built as a speed trap to earn more money for the city. I mean, it’s just all sorts of insanity. There’s a giant statue of an astronaut, one of the Apollo 13 guys, right in the center of it, which was the basis for a lot of the astronaut-themed elements in my movie. One I cut out, a dream sequence where Ryan envisions himself as an astronaut walking through Omaha. LAX, though, is sadly one of the sadder airports. It’s unattractive, just a hodgepodge of buildings. But often airports are very beautiful.

Filmmaker: And how did you first come across Walter Kirn’s book?

Reitman: I found it at Book Soup in Los Angeles. At the time I’d written Thank You for Smoking and no one would make it, so I started looking for something else. I had made some short films, some commercials, but I had never made a movie. All I was getting offered were bad broad comedies. I found Up in the Air, and there was a quote from Christopher Buckley [author of Thank You For Smoking] on the cover of the book. I thought, “If he likes the book, I guess I will too.” I started reading it and immediately found something that spoke to me very strongly. Again, I was already an obsessive flier, but it also had this kind of philosophical undercurrent about the idea of what you fill your life with. From there I began writing, and I wrote for six years. And there was this strange, simultaneous timeline because over those six years I got married, I had a child, and I kind of learned what was important in life. And as I was writing the script, the character started to take on kind of these lessons. I remember the first time I read it back. I hadn’t really gone back to rewrite to make sure it was tonally consistent, and reading the script was like reading a timeline of my own journey. The first act felt very much like me when I was writing Thank You for Smoking — very satirical, libertarian and winking [at the audience]. Through the middle it became a little more like Juno, and by the end it really was dealing with the questions that I have now.

Filmmaker: There weren’t multiple drafts over six years?

Reitman: No, there were 30 pages right before I made Thank You for Smoking, and then between Thank You for Smoking and Juno I wrote probably another 30 pages, and then I went to make Juno and I came back, and I wrote the final 60, and then went back and reworked the first two acts as well.

Filmmaker: You made some changes to Kirn’s story.

Reitman: Yeah, I had to. Alex is not in the book, Natalie’s not in the book, firing online is not in the book, the wedding is not in the book, the backpack is not in the book, and the cardboard cutout thing is not in the book.

Filmmaker: He’s headed to a wedding in the book.

Reitman: His sister’s getting married, but he never goes. [laughs] So it’s like it doesn’t happen, you know. Someone said it to me recently, and they put it best, “The book is about a man who loses it, and the movie is about a man who finds it.” The book is about a guy who is dying of an unknown disease, who thinks that some mythical company is trying to draft him. He’s slowly going insane. He goes on a giant drug and alcohol bender in Vegas and winds up in the middle of nowhere, truly lost. What I liked from the book was that it was about a man who fired people for a living who collected air miles, and who seemed to have this sense of joy from being unplugged.

Filmmaker: Didn’t Sheldon Turner do a draft?

Reitman: He wrote a spec script back in 2002, I guess, that I’ve never read. I talked recently to him and it seems that he was drawn to the book for the same reasons I was. The Writer’s Guild of America read his script and, obviously, there was enough similarity that he got credit.

Filmmaker: When did George Clooney enter the picture?

Reitman: I had always been thinking of him. It was one of those things where as my career improved, it went from, “He’ll never do this,” to “Well, maybe he’ll do it.” I gave him the script last August. I had run into George during the Juno awards campaign. I was like, “Hey, I’m writing a script for you,” and he’s like, “Oh, great. Let me know how it turns out.” Last August I said to his agent, “I’m either a week away or a month away, but I’m going to Italy with my wife. We’re going on vacation, so I’ll either finish before I go or I’ll give it to you when I get back.” And he goes, “You should go visit George!” And I was like, “I don’t know. That seems honestly like a horrible idea to me, showing up at an actor’s home. What if he hates the script?” I mean, there’s a reason why I like being unplugged in airports. The idea of going to his home in Como seemed uncomfortable to me. I said [to his agent], “I’ll get it done, and if he likes it, you tell me and I’ll show up.” I was in Italy, and I call him, I said, “So do you want me to go?” And he said, “Go! Go! Go!” “So he read it?” “Just go to his house!” “All right.” I get to his house, and one of the first things he says to me is, “So what are you working on these days?” [laughs] “The screenplay.” “Oh, right, Up in the Air. Right, it’s around here, I gotta read that.” A couple days go by, and I’m completely uncomfortable [hanging out in Italy]. I was like, “I don’t know what I’m supposed to be doing here.” And he just walked up to me at one point and said, “I read it. It’s great. I’m in.” We had a six-hour dinner that night, talked about the whole thing, got along really well. It was one of the great moments of my life.

Filmmaker: I thought the film pretty boldly riffed on his persona.

Reitman: Okay. [laughs] I mean, look, I think at the end of the day George and Ryan are very different, but certainly you can draw parallels between [Ryan and] some of the things that we associate with George. The only time he ever spoke about that was very early, it was on that first day, and he said, “I see how people are going to draw links, and I’m ready to stare that straight in the eyes.”

Filmmaker: How much do you think the film judges his character?

Reitman: Hopefully, very little. What I try to do as a director, and I’ve done this with very tricky subjects — I’ve done this with the head lobbyist for big tobacco, I’ve done this with a teenage pregnant girl, and now with a guy who fires people for a living — is to [portray] them in the most honest light possible. So hopefully I’m not judging them at all. Hopefully [the films] just serve as a mirror.

Filmmaker: Some people are slotting Ryan in a specifically American tradition of the tragic business figure, like Willy Loman or Sinclair Lewis’s Babbit. But there’s something very special about the film’s last line and image that gave him a kind of dignity for me. How did you come up with that great line?

Reitman: It’s the opening of Chapter 3 in the book. I remember reading it and I was like, “This is amazing. I’m totally ending the movie with this.” [laughs] You’re talking about the, “Most people tonight will be welcomed home by squealing kids and jumping dogs…”

Filmmaker: Yeah, but it’s what’s right after that, when he says —

Reitman: “Tonight the sun will set and the stars will wheel forth into the sky and one of those lights will be brighter than the rest, and that will be my taillight passing over.”

Filmmaker: Yes.

Reitman: Love that! I remember reading that in the book! It just came out of nowhere. When I’m adapting, I read a book, and then I read it one more time with a stack of Post-its. I put a Post-it on every page where I know I’m going to need something. I know I’m not going to just adapt it like, “This scene and then this scene.” It’s usually just like, “Oh, this line of dialogue.” I highlight it. “I need that.” Post-it. “Use that here. This line here.” And that [line] was odd, almost a poem towards the beginning of the book. It had no place or meaning where it was in the novel, but it spoke to Ryan’s existence so perfectly that for me, it was like, “Well, that’s the ending.”

Filmmaker: To me, that line speaks to the fact that people like Ryan have a function for everyone else. They give people another kind of life to fantasize about.

Reitman: I often fantasize about being Ryan. But for me that’s what the movie’s about. The movie is not about the economy. The economy is one of the many settings of this film that allow me to explore the idea of how we spend our time, how we spend our lives. The truth is that we are more disconnected than ever, and simultaneously we have a false sense of connection — connection to people, to family, to home life, community, really everything. And that’s what the movie is about. It’s the fact that there is something really enticing about just unplugging. It’s funny because I think when I was younger a movie theater was that place that I could escape to. You go to a movie theater and you are unplugged from the world. And oddly that’s become less so with cell phones and everything. You can’t disappear in a movie theater. But you can disappear in a plane. When you’re in transit, you kind of don’t exist anywhere, and there’s something really nice about that moment. Here’s a guy who is constantly in that moment, and who has found a way to live his life doing that. The fact that he fires people for a living is really just a fantastic metaphor.

Filmmaker: At the same time, I felt you did justice to the real pain of the fired worker.

Reitman: Well, I have a heart.

Filmmaker: I imagine this movie plays differently now than when you made it, because obviously more and more people have been fired in the last year.

Reitman: Well, yes. I started writing it at the tail end of an economic boom, and that has changed. When I started writing it, I wrote those [layoff scenes] as satirical. Things really changed for me when we went to St. Louis and Detroit — we happened to be shooting in two cities that were hit hardest by the economy. Suddenly you could feel the sense, unlike Los Angeles, of so many people who have lost the same job, and there’s nowhere to go. And the more I talked to people, the more I understood: No, it’s not about just maybe changing a gig or looking at a new company. It’s like your choices are: Are you going to move to a new city? Are you completely changing industries? Are you going to start from scratch at 50 years old? I mean, the kind of unthinkable things that no one should have to face, let alone hundreds of thousands of people. So all the people who lost their jobs in the movie were people who actually lost their jobs, and that [casting decision] did many things at once. Most selfishly, it brought a lot of authenticity. What was crazy to me as a guy who for a living tries to get people to be honest on film and who works with professionals at the height of their game, is that all these people just — [Reitman snaps his fingers]. The second we started talking they forgot about the camera and started saying the kind of things that you can’t write. I’m proud of the fact that we put a face to something that is otherwise just a number. It’s impossible to really understand the scale of how many people have lost their jobs.

Filmmaker: I feel your film walks a line between being somewhat unsentimental about the topic of layoffs while also containing more heartfelt moments. But did you feel the need or the pressure to offer more hope for those hurt by the economy?

Reitman: No, I don’t want to make social agenda films. There are enough directors doing that, and that’s not really what’s in my heart. You know, to a certain extent I’m a fairly cold libertarian. I think Thank You for Smoking kind of explored it best for me in that I’m this weird mix: I’m a libertarian guy, but I have a big heart, and they’re constantly butting heads. And Thank You for Smoking for me was my movie dedicated to the fact that I can’t somehow make amends with the fact that I have a heart, I want to help people, and simultaneously I believe, you know, in the Darwinian sense of life. And so I guess I approached this with the same way I approached Juno, with teenage pregnancy, and with the cigarette issue, which is I want to have as honest an approach as possible. I think that’s what makes — hopefully makes — my film different. I mean, hopefully, that’s what makes Thank You for Smoking different from The Insider, and that’s what makes Juno different than an after-school special, or any other film about teenage pregnancy. And that’s what’ll make Up in the Air different from, you know, the Michael Moore film. Even though I’m a fan of Michael Moore, and I really love what he does. But it’s just not my agenda.

Filmmaker: The film has an interesting conceit in that Ryan is kind of a middleman. He’s firing people, but he’s not their employer. And because we see the film largely from his point of view, we never really learn much about the corporations actually doing the firing.

Reitman: My wife was actually fired by one of these companies.

Filmmaker: Really?

Reitman: Yeah, and it’s interesting because I’m not sure if there’s a better [way to be fired]. It s kind of strange to sit across from a complete stranger who is telling you you’re fired. You’re like, “Who the fuck are you?” On the other hand, so many of the people that I talked to in St. Louis said, “I walked into a room, saw a guy I’ve known for 15 years, who knows me, knows my family, has been to my home, and I sit down and he pulls out a piece of paper and reads a legal document and then I had to leave.” So which one is worse?

Filmmaker: Have you had to fire people before?

Reitman: I was doing a commercial and I had to fire a 7-year-old girl. That sucked. It’s no fun. Neither side.

Filmmaker: Tell me about the approach you took towards depicting travel on screen. There’s a kind of glamour to it, but also a kind of soullessness. And, there are no travel delays. Ryan always gets to places on time.

Reitman: The whole movie works on a giant arc, and this was department-wide. The idea was that at the beginning of the film everything is perfect, and by the end of the movie everything’s real. Every [department] had a schedule of how [the design] would change over the course of the film. So at the beginning of the movie — I’ll start with the camerawork — there are a lot of fluid moving shots, a lot of wide angles. The color palette is kind of gray and clean and sleek. The lighting is more kind of half-light — very beautiful, carved lighting. The costuming, down to the extras, is very elegant. People, even the extras, are more trim. Their shirts are tucked in. They’re handsome. You get lines of flight attendants who are in perfect synchronicity. The production design is clean. Everything is kind of spotless. You get a shine on every piece of metal you can find. And then over the course of the film everything gets sloppy. By the end, whole sequences are shot handheld. Extras are kind of sloppy-looking and more real-looking people. The color palette and lighting has become a lot more like Juno; it’s become real and warm. One of the last times we see Ryan in an airport, there’s a guy mopping the floor. He can hardly get through people on the way to the desk. That was actually a very tricky endeavor because we worked at four different airports over 10 days. Twenty percent of the shoot was in airports. To always be keeping that continuity in mind was very difficult.

Filmmaker: As you know, it’s a time of drastic change in the film business. What advice would you offer someone trying to become a director today?

Reitman: It’s interesting, because just 12 years ago when I started, film festivals were it. That was the move. Make a short film, submit it to film festivals, enter the kind of democratic process which is getting into a film festival and maybe winning an award, and simultaneously writing a screenplay so that if your short film hits it out of the park, you could get people to read your screenplay and maybe get a movie made, or get an agent. But what’s now happened is the realization of something I think Coppola said back in the ’70s. He said, “The next great director will be just a kid with a video camera.”

Filmmaker: I remember that.

Reitman: And he was ahead of his time. He was right, but he wasn’t right then. It’s actually become right now. You needed three elements to come to fruition. First, you need the video [image], which was shitty but now is actually great looking. And not only that, but the look of digital has finally become a look. Cinema vérité used to be like 16mm black and white, and now it’s digital color. You needed editing, and now you can steal Final Cut Pro in about 30 minutes with a decent Internet connection and can cut your film for free. And then you needed a distribution system, and that came through YouTube. So you can now shoot, cut and distribute a film for close to nothing — depending on, you know, what kind of movie it is — and, oddly, establish yourself. I mean, my first short film was made for $16,000 and went to the Sundance Film Festival and it was the beginning of my career. My last short film I shot at home for nearly nothing, put it online, and it got millions of hits. The technology means that you need less to tell a story, and so there are going to be more storytellers. There are going to be a lot of crappy storytellers, but hopefully there will be room for some of them to break out.

Filmmaker: But it’s still hard for that work to get noticed.

Reitman: Well, film festivals still mean something. They are still a democratic platform for young filmmakers. To say, “My short film won Sundance” means something. You can probably get an agent to say, “Well, I should probably take a look at that.” [laughs] I remember reading Robert Rodriguez’s Rebel Without a Crew. He had a very straightforward attitude: just go make a movie. Now you can just go make a movie more than ever. How that relates to the business of filmmaking depends on what kind of movies you want to make. The hard thing for me is there’s no middle anymore. There are the indies, and there are the huge fucking movies, and I don’t want to make a huge fucking movie. That’s just not in my heart. I have no interest. I’m not interested in the money. I’m not interested in being on a giant set. No part of it interests me. What I want to do is make adult movies that are somewhere in the middle. I want to make movies for the same audience that used to see Billy Wilder films, Preston Sturges films, that then saw Hal Ashby films, then saw James L. Brooks films, and then saw Cameron Crowe films. The final guy in that lineage is Alexander Payne. It’s a little daunting because I’m lucky in that my last film cost $7 million and grossed $230 million, so I’m in a rare position where I get to make my movie and no one fucks with me. But there should be 10, 20, 40 directors like me trying to make these kind of movies. I like that this movie cost $25 million, but that seems to be without a category. I mean, $25 million seems to me to be a fair price for a smart movie that should be able to connect with a kind of a medium-size audience. But you feel this kind of divide where it’s just like you’re either an indie director or you’re making a tentpole, and that leaves me in kind of a strange place.