Back to selection

Back to selection

Laura Poitras’s Spy Theater

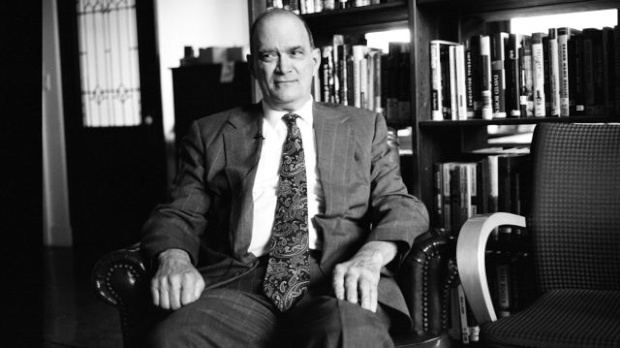

William Binney.

William Binney. There was a spooky feeling at the Whitney Biennial one Friday night this past April. Visitors to Laura Poitras’s “Surveillance Teach-In” were forcibly detained as they tried to enter the museum, while downstairs a masked man handed out leaflets with lists of addresses (NSA listening posts?), sinister in their nondescription. Slides flashed, of the anonymous desert buildings that house the servers that index our every email, phone call, transaction. And on the dais, an odd couple riffing one acronym after another: “NSA, NARIS, AES….” Hacker Jacob Appelbaum, black clad, with earrings, played something of a straight man, even as the set-ups he lobbed were laced with sardonic humor. Seated next to him, William Binney (pictured above in a photo by Appelbaum) — balding, bespectacled, and with the short-sleeve uniform of software experts everywhere — answered questions about codebreaking, domestic surveillance and something truly scary known as “cast iron,” all with the air of a man who has nothing left to lose. Indeed, Binney has nothing left to lose. A 32-year veteran of the National Security Agency (NSA), a lauded codebreaker, he is now a whistleblower cataloging the agency’s excesses. His vision of the U.S. five or ten years from now, when computational power will expand to the degree that our government will be able to scoop up vast amounts of data — emails, credit card purchases, phone calls — and then map them onto our social graphs to prosecute Minority Report-style future crimes, is a terrifying one.

After they talked, Poitras took the microphone and opened the floor to questions. “You have the opportunity to ask Binney anything,” she said. There was confusion. One man ranted about the evils of Apple’s iOS ecosystem. (“I would always stay away from proprietary software,” Appelbaum coolly replied.) A hacker type asked about some internet protocol that flew above all the non-hacker heads. “Could you translate that into English?” someone shouted from the back. A woman said the telcos had placed cell phone antennae on her roof and how could she know they were not spying on her?

For her program as part of the 2012 Whitney Biennial, Poitras created an event that was part technological seminar, part radical teach-in, and part DeLillo-esque spy theater. The evening was full of trenchant lines by Binney: “The data trail we leave behind tells a story that may be full of facts but may not be true”; “Whatever happens to any of us, it was murder”; and, finally, “I have made clear to my supporters I will never commit suicide.”

Four months later, Poitras has made a short video for the New York Times (not embeddable, but linked here), in which she interviews Binney. And she’s also written an Op-Ed for the Times that is adapted from her documentary work-in-progress: the final chapter in her trilogy of films about post-9/11 America. From that piece:

To those who understand state surveillance as an abstraction, I will try to describe a little about how it has affected me. The United States apparently placed me on a “watch-list” in 2006 after I completed a film about the Iraq war. I have been detained at the border more than 40 times. Once, in 2011, when I was stopped at John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York and asserted my First Amendment right not to answer questions about my work, the border agent replied, “If you don’t answer our questions, we’ll find our answers on your electronics.”’ As a filmmaker and journalist entrusted to protect the people who share information with me, it is becoming increasingly difficult for me to work in the United States. Although I take every effort to secure my material, I know the N.S.A. has technical abilities that are nearly impossible to defend against if you are targeted.

(Photo: William Binney portrait by Jacob Appelbaum.)