Back to selection

Back to selection

Five Questions with Mark Lombardi: Death-Defying Acts of Art and Conspiracy Director Marieke Wegener

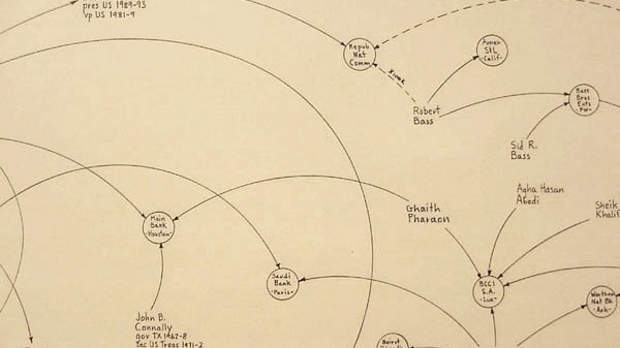

In the years since his death in 2000, the work of artist Mark Lombardi has seemed even more prescient and relevant than it had during his lifetime. Lombardi’s finely-etched drawings, filled with annotated lines, circles and squiggles, traced the flow of capital and political power between various government, private and underworld actors. His subjects were American foreign policy, crime, corruption and conspiracy, and his artwork consisted of not only his drawings but the investigative work required to create them.

Lombardi’s drawings reference the drug wars, the BCCI scandal, Charles Keating and the savings and loan scandal, and Iran contra, but after 9/11, interest in his work only grew. His work, which he called “Narrative Structures,” seemed to sketch the backstory of the following decade of American foreign policy.

German documentary Mareike Wegener has made the first doc about Lombardi and his work, Mark Lombardi: Death-Defying Acts of Art and Conspiracy. It’s a solid introduction to not just the finished drawings but also to Lombardi’s rigorously old-school research process, which filled thousands of note cards and file cabinets. Wegener grounds her film within the art world, using critics and art historians to situate Lombardi’s work not just within Conceptual and Neo-Conceptual art but also connecting it to centuries-old traditions of landscape painting.

Lombardi committed suicide in March, 2000, and while some conspiracy theorists and 9/11 Truthers have speculated foul play, Wegener in her film focuses on his life and his art, all the while acknowledging its continuing political relevance.

Mark Lombardi: Death-Defying Acts of Art and Conspiracy receives its New York MoMA“premiere today at MoMA, where it will continue in a one-week run. The director will be present at tonight’s showing for a Q&A. I asked Wegener the following questions about her film via email.

1. How did you discover Mark Lombardi and what attracted you to his work?

I think what draws me to examine art as a subject matter in my films is the wish to understand what good art is about. It requires a great deal of depth because it means to go back to the original source – the work of art – as opposed to relying on criticism and art history writing. This is also the reason why I kept biographical information on Lombardi to a minimum in the documentary. I wanted to sound out the impact art can have, and the possibilities it creates for the viewer. Lombardi is the perfect example for this, because in the end, what he created can’t be reduced to him as a person or as an artist – his work is way larger than that. And I feel that this is an idea that gets lost today. We give too much attention to the connection between the artist’s ego and his artistic output instead of looking at what really is at stake in his or her work – and ultimately, what it can do for us.

To make a film enabled me to go beyond the limitation of the current art discourse. And the questions arising from this are important to my partice as a filmmaker as well: Why am I doing this? Who am I doing it for? What kind of a world do I want to create within my art and through my artistic practice?

2. Mark’s work is very much associated with the pre-9/11 U.S. foreign policy. Now, 11 years after 9/11, is his work as relevant?

The current state of politics and society – and pretty much everything else that forms our reality – is very much owed to what happened 11 years ago. We are living in its aftermath. In my opinion it is a truly terrible situation. But 9/11 didn’t just happen, it is not disconnected from history or the underlying geopolitical power structure that led to it. And this is exactly what Mark Lombardi’s “Narrative Structures” reveal. The world is defined by connections between various types of entities – individuals, companies, institutions, state organizations, etc. – and there is business involved, and there is big money involved. Ultimately, what Lombardi’s work shows us, is the intertwining of economy and politics. And what this leads to is the fact that politics is no longer the place for practicing political thought, but rather for implementing economic interests. There is nothing more relevant today than finding a place where political thinking can be expressed and fruitful again. By looking at Lombardi’s work I came to think that art could be this place.

3. What were the challenges you faced dealing with a subject who has passed away and is not able to address the questions sparked by his work?

There were two major difficulties. First of all the film had to communiate a great amount of information, for processing information was the basis of Lombardi’s work. So I had to come up with a way of transmitting facts that avoided the language of a newscast, that didn’t become pure illustration. The other problem was, of course, Lombardi’s absence. There is no way of portraying the ideas of someone who is dead [without using a] form comparable to indirect speech. And for indirect speech to become something vivid and lively it needs some tricks. I applied the filmic tradition of the political thriller, which had its heyday in the ’60s and ’70s here in the States and which is experiencing a comeback these days, in order to find a solution. The parameters of the film, the way it is shot, the motifs it shows, the way the narration is build up, all go back to this genre, the only exception being the anticlimactic ending of the film, which I chose in order to avoid the scandalization of Lombardi’s death.

4. Did you investigate some of the various conspiracy theorists who reference Mark as part of the 9/11 Truth Movement? Did you think of expanding the part of the film dealing with his death and the aftermath?

I think to reduce Lombardi to the figure of a conspiracy theorist does not do him justice. One of the main characteristics of conspiracy theory is that it creates room for mysticism and speculation. Furthermore it uses facts to express opinion and to confirm and illustrate a pre-existing world view. I think none of this is accurate when talking about Lombardi, which is why I tried to keep a distance to conspiracy theory as such. Lombardi does not express opinion in his work at all, but he affirms the world as it is. The questions of whether something has to be done about it and what that would be is a consideration entirely left to the viewer.

His death leaves us with many questions, it is true. But any attempt of giving answers would be counterproductive. The film neither wants to scandalize his death as a possible murder, nor does it want to feed into the idea of the clichée of the emotionally and psychologically unstable figure of the artist. Again, this would deprive the film and its subject matter of its strength and true meaning.

5. How did you get this film produced, and what are your hopes for it?

The film is a German production. The funding system in Germany works quite differently from that of the United States, where it basically doesn’t exsist. I was given a research grant by a local film fund, and after authoring a very detailed script as a result of my research, the French-German broadcaster ARTE showed interest in a co-production and we could then gather production funds from federal and local film boards. The finished piece then had a theatrical release in Germany this summer and it traveled the festivals, mainly in Europe.

As I see this film as some sort of a consideration and evaluation of what is at stake in Lombardi’s work and in art at large, I hope more people will be able to have access to it. And I hope it can give more popularity to Lombardi’s work, so that maybe people who lost their interest in art find a new point of entrance. Because art is important.