Back to selection

Back to selection

Game Engine

by Heather Chaplin

Hard to Kick: On Videogames and Addiction

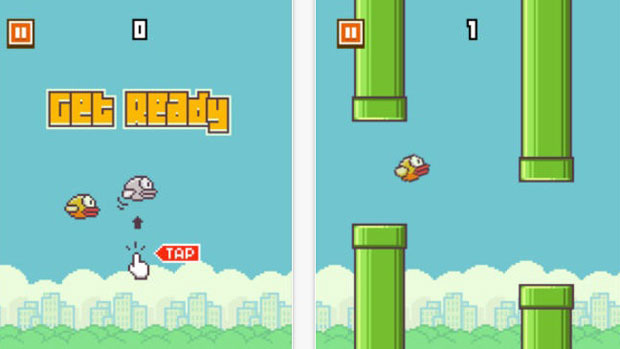

Flappy Bird

Flappy Bird February 12, 2014: It was something of a watershed moment last weekend when Doug Nguyen, creator of Flappy Bird, the world’s most popular free app, pulled his game from the App Store. The app was estimated to have generated for Ngyuen $50,000 a week in advertising revenue. The problem? The game, said Nguyen, was addictive. He told Forbes, “Flappy Bird was designed to play in a few minutes when you are relaxed. But it happened to become an addictive product. I think it has become a problem. To solve that problem, it’s best to take down Flappy Bird. It’s gone forever.”

In Filmmaker‘s Fall, 2012 Game Engine column, Heather Chaplin wrote about the physiology, psychology and morality of videogame addiction. With a tip of the hat to Nguyen, we are reprinting it today. — SM

Let’s start with the rats.

You’ve probably heard of the famous behavioral psychologist, B.F. Skinner. For our purposes here, know that Skinner invented the operant conditioning chamber, or Skinner box, where he experimented on rats and pigeons to determine the effectiveness of rewards and punishments in shaping behavior.

Picture a glass box with a rat inside, a lever that distributes pellets of food and a tube for water. The first thing Skinner discovered was that by giving the rat a pellet every time it pressed the lever, the rat soon learned to keep pushing the lever. Skinner called this “shaping” — his word for getting his subjects to consistently engage in a particular behavior. Then he tried something called the random ratio schedule. In this, Skinner rewarded the rat with food pellets but only after a random number of hits on the lever. Because the poor thing couldn’t predict when the food was coming, it would hang out pressing the lever over and over and over.

I heard about these experiments in high school and found them distressing on a deep level. I felt so sorry for those rats — and us — because they (we) would do anything for a “reward.” I was particularly struck by what my friend Alix and I came to call “the random pellet theory” (or “the random ration schedule”), which seemed to apply to dating and why the guy who sometimes calls and sometimes forgets to call was always the one you couldn’t get out of your mind.

But I’m digressing. This is not a column about dating.

This column is actually about addiction, specifically videogame addiction. And that subject has everything to do with operant conditioning and rats in cages — and even, a tiny bit, about angry pigeons.

Last week I went to a talk at New York University’s Game Center to hear Dr. Bennett Foddy. Foddy has degrees in physics and philosophy and is a senior research fellow and deputy director of The Institute of Science and Ethics at Oxford University. He’s written extensively on addiction — and also makes indie videogames in his spare time. (QWOP, GIRP and Little Master Cricket are a few.) Foddy was at NYU to say something game designers and players hate to hear: videogames can be addictive and designers have an ethical responsibility for creating a product that can cause people harm.

“The design of videogames is the design of addiction,” Foddy said.

The controversy over games and addiction has been going on since videogames were invented. You may know someone you would describe as addicted to videogames. Maybe you’ve even experienced something that felt like addiction yourself. But game people tend to be a defensive lot, and generally you bring up the subject at your own risk. Indie game designer Jonathan Blow caused massive controversy several years back when he suggested that game designers were stealing people’s free time by designing games to be addictive rather than enjoyable or meaningful. It came out of a talk in 2007, and people still bring it up and get mad about it.

But Foddy has been studying addictions — and rats in cages — for years and has developed an argument that rings true the way good, rigorous philosophical arguments do.

First of all, according to Foddy, addiction to videogames is possible in a way it’s not with books, visual art or painting. This is because of the interactive nature of games and has everything to do with that Skinner phrase, operant conditioning. Just like the rats pressing the lever in their cages are being shaped to keep pressing them, game players are engaging in lots and lots of repetitive actions followed by lots and lots of little rewards. This in itself builds addiction, Foddy says. Players are shaping themselves just like Skinner’s rats were. Every time you do an action in a videogame, you’re being trained to want to do the action again.

“There’s something in the act of the repetitive behavior that creates the addiction,” Foddy said. “This is key.”

Another rat experiment: one rat gets a shot of heroin every time it pushes a lever. The rat in the next cage gets nothing when he pushes his lever — but he does get a shot when his neighbor gets dosed. At the end of the experiment, researchers found that the rat administering its own shots was addicted, while the one that was getting the shots secondhand wasn’t. In other words, creating cause and effect is crucial in building addiction. And videogames are all about experiencing cause“The urban myth of the person who gets shot up with heroin and ends up addicted against their will, it’s not true,” Foddy says. “In order to get addicted to heroin, you have to be injecting yourself. Addiction needs the operant conditioning.” In games, a fast response to an action taken is a hallmark of a good game. Action. Reward. Action. Reward. Action. Reward.

Then there’s the random ration schedule, or what my friend and I used to call the random pellet theory. Rare is the videogame that does not have a random reward schedule built into it. It’s a well-known fact among game designers that rewarding your players randomly is the best way to keep them playing. In Everquest, for example, you know practicing a skill will get you more skill points, but you don’t know when. Back in 2001, Microsoft Game Researcher John Hopson wrote in Gamasutra that a fixed reward schedule (giving the rat his pellet every time he pushes the lever) leads to bursts of activity followed by long periods of inaction. This is a problem if you want your players to keep playing — say, your business model is a monthly subscription or by-the-hour. With a variable reward schedule (randomly distributed pellets), player activity continues unabated, Hopson observed. “If what you’re looking for is a high and constant rate of play, you want a variable ratio contingency,” Hopson wrote.

Foddy also talks about the use of what’s known to psychological researchers as “the sunk cost bias.” This refers to the way people don’t want to quit something into which they’ve already put a lot of time. In most role-playing games, for example, the first levels are easy and get significantly harder the longer you play. In massively multi-player games like Everquest or World of Warcraft, getting to level two takes a few minutes, but once you’re at the higher levels it takes hours, days, weeks to move up.

With the changing business models in the videogames business, all this becomes increasingly relevant. With a console game you plop down your 50 bucks at GameStop, and then it doesn’t really matter to Electronic Arts or whoever if you play for five minutes or 100 hours. But with the monthly subscription fees of massive multi-player games, suddenly it becomes very important that players keep playing. There can’t be down time in an MMO because people will walk away. Or take the casual game market, with its “freemium” model. The first levels of a game are free, but then, once you’re hooked, you have to pay to keep playing. Foddy says telling the player she can’t keep playing right as she’s at the peak of an addictive cycle is unethical.

“That’s acting like a drug pusher,” Foddy says. “You’re being taken advantage of when you’re vulnerable.”

It’s worth mentioning that Foddy doesn’t think all addictions are bad. He’s addicted to coffee, he says, but it’s not harmful to him and the ratio between craving it and the pleasure he gets from it is more than acceptable; so, too, with videogames. The question should be, Foddy says, do the things in the game that made them addictive also make them more enjoyable? Do you increasingly crave it even as your pleasure in the act of playing decreases? An ideal game, he says, is one where players become addicted for a short period and then move on.

“You’re shooting for benign, minor addiction that the person will break free of eventually,” Foddy said. “I want them to play intently for a while and then get over it.”

And the ethical question is two-fold: Are game companies addicting people just to take their money without giving them anything rewarding in return (the Jonathan Blow school of thought) and, if designers know they’re creating something addictive, what kind of responsibility do they have to players?

“If we’re trying to engineer addiction, then there’s the question of whether we’re responsible when people get addicted, and should we try to help them or even stop them,” Foddy says.

He suggests an ethical test: “Are the things that make my game more addictive also things that make my game more enjoyable?”

If you’re just creating strong cravings in people to engage in behaviors that don’t even give that much pleasure, you’re limiting people’s choices in life. “The onus is on the game designers to make sure their games aren’t like this,” Foddy says.