Back to selection

Back to selection

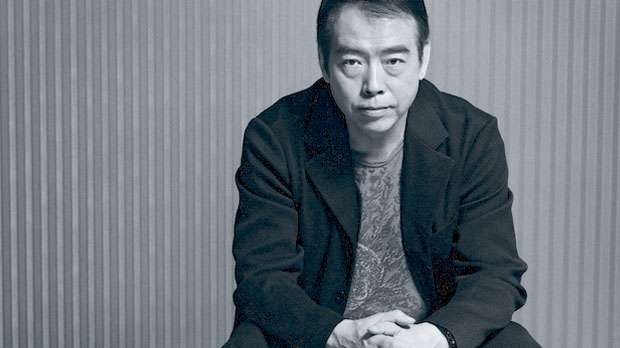

“The Studios are Dead:” Chen Kaige on China’s New Filmmaking Machine

It’s fitting that Chen Kaige kicked off TIFF’s Century of Chinese Cinema program last week in Toronto where he introduced screenings of his films and spoke about his career in two public talks. The movies of the Fifth Generation filmmaker cover several eras of Chinese society, ranging from pre-World War Two in Farewell My Concubine (1993) to today’s social media of Caught in the Web (2012). More importantly, Chen is a key figure in elevating Chinese cinema to the world stage, starting in 1984 — when his first film, Yellow Earth, shattered the tyranny of state-sponsored propaganda films — then in 1993 when he captured the Palme d’Or at Cannes for Concubine. The grand irony is that these films couldn’t get made today.

“Yellow Earth? No one would come to see this film today in China,” Chen told Filmmaker. “The people walking into theaters and sitting in the dark are all in their twenties. They know nothing about history and are not interested.” Instead, today’s youth face basic problems of finding a place to live and a landing a job. “Their choice is to find something to make them relax. They don’t want to think. They need to think a lot in their daily lives already. Film is just entertainment.”

Nowhere on the planet is urbanization so accelerated than in China. How would a twentysomething in Shanghai relate to Gu Qing, the soldier in Yellow Earth who journeys to remote China to collect folk songs from peasants in order to boost the morale of the Communist army? Would today’s youngster in Beijing appreciate the beauty of Zhang Yimou’s breathtaking cinematography? Or is Yellow Earth a museum piece like Easy Rider is to North Americans — a film that announced a new generation of filmmakers and shook the establishment of a bygone era.

“In the past we would say that we want to make a movie in order to say something,” explains Chen. “If you tell investors that now then they’ll kill you. ‘What we want to do is make money. How can you say there is something you want to express in your films?’”

Chen predicts that Chinese filmmaking is quickly adopting the Hollywood model where the market — not the state — censors filmmakers in what subjects to tackle. Costume dramas? Forget it. “If you want to raise money from the market, you have to make the audience happy. You limit your ability to make great films….You see this in Hollywood with so many ‘machine’ movies [action sequels].”

Chen finds the current state of filmmaking both good and bad: “The good is that the market is growing bigger.” China’s box office receipts mushroomed 30% in 2012, and nine new movie screens go up each day in the largest movie-going market after the U.S. “The bad thing is fewer good movies are made today,” Chen adds.

However, he finds hope in another visual medium. “A lot of young people [and also] middle-aged people realize that the Internet is the way to express themselves to show what they think about society and the problems they face every single day.” Driven by smartphone sales, China’s internet usage rose 10% in 2012 to staggering total of 564 million users. “This is reality whether you like it or now,” says Chen. “If you don’t adopt to the Internet you are not a modern man. You are living in the past.”

The Internet is the focus of Chen’s latest movie, Caught in the Web, about a young woman who’s instantly vilified after a video clip of her refusing to give up her bus seat to an old man goes viral. Unconsciously, the film’s mob mentality echoes the horrific public persecutions during the Cultural Revolution of the 60s that Chen remembers as a youth. “Maybe this is part of human tradition that people find someone they don’t like and attack them. That’s why there is cyberbullying all the time. Maybe one word can kill people.”

Despite the seismic shift in China’s film industry, Chen feels that he has more artistic freedom today. “Twenty-five years ago you could only work with certain studios.” Like the studio system of classic Hollywood until it crumbled in the late 60s, the Chinese studio head was the boss, telling filmmakers what to do and dictating their budgets. “But now there is no studio system at all. The studios are dead in China. Every single film is made by a private company. I think it’s good.”

Surprisingly, Chen doesn’t miss the old days where he didn’t have to worry about his films’ box office tallies. “It’s not wrong if you want to make an audience happy. They pay to come to see your film. You don’t expect them to leave the theater with negative emotions or sadness.”

Artists reflect changes in their societies, and Chen Kaige certainly does in China. In his lifetime, The People’s Republic has morphed from a socialist collective into a supply-and-demand economy. Yet one mystery endures for the filmmaker regardless of the system: “You always want to make sure that your film is appreciated by your audience, but how can you know? You never know.”