Back to selection

Back to selection

Pacific Rim: Asian American International Film Festival

Forgetting to Know You

Forgetting to Know You Some titles that blur the gray line between ideology and pleasure could well have been fodder for battle between the just-concluded New York Asian Film Festival (NYAFF) and the Asian American International Film Festival (AAIFF), which runs July 24-August 3. The former is larger and younger (b. 2002) and comprised almost entirely of entertaining generic fiction; the latter, smaller, older (b. 1978), and more diverse, a politicized showcase in which fiction, documentaries, and hybrids share pride of place. Yes, there is telling overlap in their respective agendas.

The AAIFF divides its 26 features into six strands (44 shorts are branded separately): Triple A (Asian American Achievements); LGBTQ Features; Remembering the Forgotten War (Korean, Pacific, and Sri Lankan Civil); Exploring Asian Filmscapes; Taiwan Cinema Days; and Celebrating Female Filmmakers: In Memory of (Filipina director) Marilou Diaz-Abaya.

Asian American Achievements has a few good films, but is limited to what has been made independently by and about Asian Americans over the past year. Several of the LGBTQ choices appear quaint by U.S. standards; interestingly, the majority are about women. The other sections are mixed bags, the umbrella theme occasionally overshadowing form. Remembering the Forgotten War recalls exceptional small Italian festivals like Turin, Bologna, and Pesaro that nearly exhaust the cinematic documentation of a specific topic or era. I’m not a fan of Diaz-Abaya’s oeuvre, but programmers are, and should be, more generous than critics. I have not seen anything from Taiwan Cinema Days.

Exploring Asian Filmscapes is by far the most consistently impressive, in large part because guest co-curators L. Somi Roy and La Frances Hui have cherry-picked from all over Asia. (My only reservation is occasional exoticism, insofar that the ambience sometimes overshadows the screenplay.) Hovering presences in most of the films include self-explanatory economic desperation; and death, more complicated to understand. Are the clichés valid — that the culture of fatalism is well-entrenched in most of Asia, and that the end of life is less feared than in the West?

Roy and Hui have assembled a lineup of Asian films that often takes you on insistently unsettling journeys to the margins. “While we were looking at geography and variegated forms and genres, two unexpected currents emerged,” Roy explains. “One was queer cinema. It overlapped with the other: films with a sense of periphery, of lesser heard voices from South and Southeast Asia. In part, this was a result of choosing the lesser seen cinema of Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka rather than merely focusing on the larger, better known cinema of India. These films gave face to individuals who have remained in shadow in their own societies, be it a former Tamil Tiger or a transgendered Pakistani khusra.”

Asian CineVision (ACV), the guiding force behind the festival, began in Chinatown in 1975 as a grassroots organization called Chinese Cable TV (CCTV). The change in title a couple of years later marked a sensible shift in direction that paved the way for the AAIFF, which today includes off-screen programs like workshops, panels, and brief script and filmmaking competitions that invigorate up-and-comers. Here I focus on the on-screen component, reviewing the five must-see feature-length films, listed in alphabetical order. Retroactively, I notice that they are evenly dispersed geographically. Is this coincidence, curatorial acumen, sign of a general wave of Asian and Asian Diaspora films, or all of the above? See, and ye shall find.

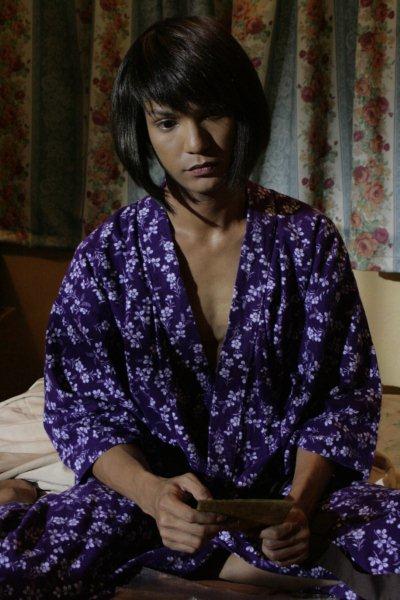

Forgetting To Know You (Quan Ling, China)

The imprimatur of Chinese auteur Jia Zhang-ke is all over this strong debut that he produced, part of his kickstarter “Wings” project. Novelist Quan Ling, however, puts her own feminist spin on the material. She has successfully crossed over to screenwriting and directing, creating an artwork as spot-on socially critical as it is boldly cinematic.

Xuesong (a tour-de-force by Tao Hong; see photo above) is an attractive if unembellished convenience-store clerk in the stultifying backwater of Baisha. The hot, boring town is a few hours from the escape hatch of Chongqing, a large city that is a magnet for new money. She is responsible, but her untamed, abusive carpenter husband, Cai (Guo Xiaodong), squanders his earnings, drinks too much, and explodes at the drop of a hat. Their seven-year-old daughter serves chiefly to reveal Cai’s deeply hidden kind side. Xuesong and Cai are reciprocal spies, peeking at each other’s emails and cell-phone call lists. They hardly know each other; in fact, the Chinese title translates as “Unfamiliar.”

The film is less about this nuclear family than it is about Xuesong and her relationships with three men, including her spouse, each fulfilling a different need. They represent various economic strata in contemporary China. Cai is the frustrated day-laborer who drains her energy; flirt object Wu (Zi Yi) is a carefree cabbie who ekes what he can out of the system without running up against it, and provides the otherwise stone-faced Xuesong with the attention and warmth she lacks on the home front; and Yang Jiucheng (Zhang Yibai) is the ex from high school who has made a fortune in real estate and wields the power that comes with recent wealth — even if its source is dubious. He is a rock that she turns to in times of need.

Quan Ling methodically deconstructs the mythology surrounding maleness in China. Quesong recalls the disappointment expressed by Cai’s mother when she gave birth to a girl. The director subtly contrasts Quesong’s isolation, behind a cash register or at home on the couch, with the camaraderie found in men-only spots like the neighborhood gaming parlor and shared by guys out clubbing with hookers. An Ibsenesque ending packs a quiet but mighty dramatic punch.

Ubiquitous motorcycles add oomph to the dull townscape. Like most of Jia Zhang-ke’s films, the sets are authentic, the feel neorealist, the camera work mobile, the sound primarily ambient. Quan Ling even includes a performance piece, a signature Jia Zhang-ke motif, but hers takes place in an empty, abandoned auditorium in which Wu sings to Quesong while pretending he is in front of a full house. And as in her mentor’s films, television screens occupy a prominent place.

Him, Here, After (Asoka Handagama, Sri Lanka)

“Him” — he is not given a name — is the protagonist of Sinhalese director Handagama’s beautifully crafted film, a rarity in which Tamil actors speak Tamil — not the Tamil of the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu, where a real Tamil film industry exists, but the local dialect.

The outsider status of the production (only the featured leads are professionals) gels nicely with the storyline, which graceful reframing and long tracking shots help to convey. Him (Dharshen Dharmaraj) is a former Tamil Tiger recruiter in Jaffna whose charisma enabled him to enlist many of the town’s young people to fight a civil war that they lost. Having done an obligatory stint in rehab after the 2009 surrender, he is the only fellow from town to return alive (except for those who recruited, then emigrated instead of going to battle). Although he remains a striking presence — very dark, handsome, and beefy — he has lost his allure. He is a constant reminder to the townspeople of their failed dreams and lost children, a pariah on whom they pin blame and project grief.

Shunning turns to outright hostility. After he moves in with his ex, a draft dodger who is now a widow with a young child, locals toss a shrouded corpse into his garden. The theme of burial keeps popping up: a rifle from the war hidden underground, his mother’s jewelry dug up so that he can pay extortion fees for a necessary driver’s license. The metaphor is hard to miss. Is uncovering the past cathartic or damaging? When asked to talk about the war, he answers, “No point.”

The owner of a small jewelry shop fires his security guard and hires Him for the post. Actually, it’s not really a break at all in a region devoid of economic opportunity. The store is a front for a substantial smuggling operation in this coastal city, and Him is “set up,” in his own words, to participate.

Meanwhile, the terminated employee and his family stalk and shame him. He ends up tending to the man’s amazingly optimistic, battered, and also unnamed “Wife” (Niranjani Shanmugaraja), a woman who has lost everything, including pride (it is intimated that she was repeatedly raped in a camp). And she tends to him. His ambivalent feelings for her become a tool in the hands of his fellow criminals.

The tall palmyra trees distinctive to the Jaffna area and the dune-like landscape are perfect backdrops for the formidable figure of Him, his increasing paranoia, and the illicit activities he engages in. Softer scenes, such as when Him prays at the local Hindu temple or joshes around with Wife’s innocent kids, help maintain a suitably smooth editing rhythm. The film recently opened in France to ecstatic reviews in the mainstream press. That would not happen here. Were it not for the AAIFF, we would be unable to watch it. What is wrong with this picture?

Linsanity (Evan Jackson Leong, U.S.)

Leong and editor Greg Louie marvelously document the high ups and low downs of basketball icon Jeremy Lin’s athletic life. I specify “athletic” because the film concentrates almost exclusively on Lin and the sport. Yes, the tight bond with, and support from, his immigrant parents and American-born brothers are there, as are the reconnection with his Taiwanese ancestry and his powerful Christian faith. “God, family, basketball” is how he explains his priorities. He taught basketball at a Christian school and regularly attends fellowship.

But if you are out for evidence of a love life, indeed of any social life outside his family network, you will be disappointed. This may be best, because the extremely private Lin is really a typical American suburban kid, a child of California, gawky and inarticulate (most sentences begin with “like”), who is driven when it comes to hoops and courts but otherwise lacks edge. A very nice guy, it appears, but all his blankets are covered with cartoon and space kitsch. Athlete, not aesthete.

To its credit, the film doesn’t get into the Linsanity craze until nearly 20 minutes before the end. Foregoing spectacle (except for game footage) in favor of an individual’s checkerboard quest, it follows his journey from Palo Alto High, through his two-week winning rampage in 2012 when he finally proved himself while subbing for benched New York Knicks point guards, up until the validation he had been desperately seeking, a $25 million, three-year contract with the Houston Rockets.

Fortunately, Leong had commenced shooting before Lin became a known quantity, so he was in a unique position to chart his evolution. Clearly he gained Lin’s trust, for the player is open with him in talking-heads segments. Leong also had access to family home movies and video from high school onwards that provide context and continuity. Louie neatly stitches together scenes such as Lin dribbling today and Lin dribbling as a youth — probably a miss in lesser hands.

The game footage keeps the film moving at a brisk pace. That is the nature of basketball, but Leong’s focus on Lin in the games keeps it from rambling into an overlong sports montage. In some of these scenes, Lin just sits on the bench. You feel his frustration. When he does perform, it is often mediated by sports commentators, with his agent and assorted coaches reflecting on Lin, what he’s endured, and what makes him tick. Leong builds suspense in his treatment of the draft rounds that could make or break the young player and in his handling of the Kobe Bryant-Jeremy Lin media battle.

Lin is not naïve about the negatives in becoming an Asian American basketball star in the U.S. He talks about the slurs he has encountered. Leong inserts excerpts from talk shows in which people like Jon Stewart and David Letterman spit on the absurd vitriol accompanying his rise to fame, like a newpaper caricature of his head popping out of a fortune cookie. Even more insidious is Lin’s realization that the Golden State Warriors had picked him up after Harvard as a marketing tool to ensnare the northern Californian Asian community into the ticket office.

Requieme! (Loy Arcenas, Philippines)

“Filipinos are slippery” is a constant, affectionate refrain throughout the film. Is there any validity to the claim? Arcenas deftly interweaves the stories behind the deaths of three different Filipinos and the aftermath, milking them for black comedy and poignancy, and using them as weapons to expose rampant bureaucracy and corruption.

A politically active and opportunistic woman, Swanie (Shamaine Centenera Buencamino), and her estranged pre-op transsexual son, Joanna (Anthony Falcon), are by chance involved in the parallel acquisition of necessary permits and payment of outrageous sums to bury two of the characters. Mom is a town councilor in the village of Sta. Maria. She latches on to the myth rooted in the case of Gianni Versace-killer Andrew Cunanan that Filipinos are victims all over the world. Joanna takes charge of the fight in the morgue and at the cemetery in Manila to properly bury an elderly friend, a neighborhood soda vendor. The third death, announced on TV, is of a Filipino worker in Dubai who had died on the can in a mall he is helping construct. His wife cries endlessly to the cameras, the more so when airplanes transporting her husband’s body land over and over again at the wrong airports.

We see a number of other television programs (setting the stage for a potent final scene), mostly news announcements about designer Vidal Valler’s assassination by gay Filipino Adolf Payapa, a very distant relative of Swanie living in New York. Swanie thinks that bringing his body back will put Sta. Maria on the map and help her in the upcoming municipal elections. Again, getting the body home is a major problem, in spite of support from higher-ups. It’s difficult to take on the U.S. government. Just ask Edward Snowden and President Evo Morales of Bolivia.

The solution is a hilarious fake funeral that is perfectly executed, especially when it comes apart. Perhaps this inspires the double meaning of the title, the funereal word “requiem” and “quime,” a colloquial expression among Filipino youths today that is akin to the American “whatever!” and also, according to Arcenas, “a gentle fuck you.”

Like most transvestites, Joanna endures taunts and degrading questions, especially in this conservative, religious, and macho society. Yet she is happy and generous — she gives up her breast transplant money to contribute to her friend’s burial — a self-sufficient clothing designer with a loving boyfriend and a sensible head on her shoulders. It appears that Swanie had pushed her gay son out of Sta. Maria, but the truth is never known. Neither is the future, for Arcenas declines easy closure.

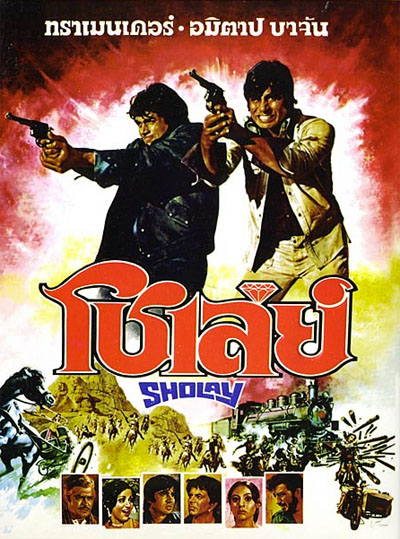

Sholay (G.P. Sippy, India)

This classic, big-budget Indian film from 1975 is showing in 3D — an extra layer of shock on top of its general bizarreness. Sholay flouts conventions of genre, characterization, and narrative (killings are repeated in slo-mo; an out-of-place offhand comment often marks the transition to a new setting and situation).

Self-consciously evoking the work of Sergio Leone, this is a colorful example of the mélange known as the masala western (“something for everyone,” says Roy). It is set in a rugged, rocky landscape, not quite Monument Valley but a South Indian setting that could pass for a southern Californian Hollywood locale. Horses carrying extras gallop by, and Sippy stages elaborate shootouts with his leading men. But the bad guys-versus-lawman set-up at the beginning of the film, which takes place during a train robbery right out of American silent films, evolves into a scenario in which the enemies bond to challenge another, more threatening group of outlaws. Redemption for the lawbreakers in phase one comes quickly; it does not wait for the usual obstacles that only delay a grand climax.

This Indopudding is also a road movie, and a comedy to boot. The protagonists are two engagingly underworld pals, Jai (heartthrob Amitabh Bachchan in the film that made his name) and Veeru (Dharmendra, a fine comic and the better actor), who pass through corrupt towns and surreal prisons (in a silly extended sequence, a warden imitates Chaplin imitating Hitler in The Great Dictator).

After their final release, they head overland to the provincial town of Ramgarh and the nearby luxury ranchhouse owned by their erstwhile foe, former Sheriff Thakur (Sanjeev Kumar). He employs them as guns-for-hire to capture the regional bandit leader, Gabbar (an effectively creepy Amjad Khan), who has decimated his family and torn off his limbs as punishment for a conviction. The theme of revenge is the prime motivator for much of the action.

Along the way they meet colorful characters, such as Basanti (Hema Malini), a tangewali (buggy driver) who never stops talking, although it does not prevent her from becoming Veeru’s love interest. Once at Thakur’s estate, they encounter some odd, mostly overdrawn townspeople. Not to be outdone, Jai falls in silent love with his host’s widowed daughter-in-law, as introverted as Basanti is outer-directed.

Malini is a talented South Indian dancer whom Sippy puts to good use in several obligatory musical numbers. But the most powerful musical scenes are those in which Jai and Veeru, both handsome, lithe, and virile, sing and carouse on the road. Their lackadaisical manner, and the sheer number of mutual caresses — which come to a head in a tragic, intensely melodramatic climax — undermine the love scenes and songs they have with the women. At the finale, the two fiancees look shocked, as if only now they realize that they are not the primary beloveds. Jai and Veeru are so much closer than BFFs that you could imagine this film in the festival’s LGBTQ program, and I do not think that is a projection.

K. Mahajan’s camerawork is glorious, and Sippy moves the film along at a rapid pace. He was not going to allow anyone to become impatient until the 200-minute running time had run out. This is surely opium for the masses, but it is great fun and refreshingly outrageous — the perfect counterpoint to the AAIFF’S more reverent fare.