Back to selection

Back to selection

Blood on the Motorway: Alexandre Moors on Blue Caprice

Blue Caprice

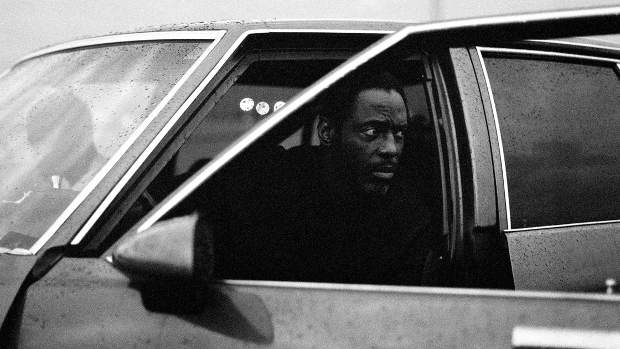

Blue Caprice The title character in Alexandre Moors’ frequently stunning feature debut Blue Caprice is a mid-sized sedan, the type used by police departments across America as the principle member of their fleet, its steely menace a constant presence as it winds its way through nondescript, wan-looking American streets. The sedan in question in Moors’ film was also a police car, at least before it was retrofitted for terror by John Allen Muhammad and Lee Boyd Malvo, who drilled a whole in the trunk from which the 17-year-old Malvo, at the ex-U.S. Army marksman Muhammad’s urging, shot 10 people to death during the 2002 Beltway Sniper Attacks.

Scores of unsuspecting pedestrians, often in parking lots and or driving under overpasses, were cut down with a chilly nonchalance by this sinister duo, brought to terrifying life by the remarkable Isaiah Washington as Muhammad and Tequan Richmond (TV’s Everybody Hates Chris) as Malvo. Washington, who is in reputation-rehabilitation mode following his tumultuous exit from Grey’s Anatomy five years ago, crawls under your skin as the black Muslim, Gulf War vet Muhammad, whose essential motivations remain as opaque as the film’s built-for-maximum-glide visual aesthetic. Stark blues, vibrant, rain soaked greens and gun metal greys dominate the palette and provide an apt visual metaphor for the storm brewing in Muhammad’s mind.

Moors, a Frenchman who has built a strong reputation in the commercial world and who cites Claire Denis, especially her Beau Travail, as a huge influence, artfully disjoints the storytelling, keeping us at a cool distance from events over the course of a story that takes us from Muhammad’s Antiguan hideout (he had kidnapped his children and brought them there, engaging in credit card and immigration fraud to do so) to Tacoma, Washington, where he and the young Jamaican immigrant spent a year, most of it crashing at the home of a military buddy of Muhammad’s and his wife, who are brought to startling life in the film by Tim Blake Nelson and Joey Lauren Adams, and then to the fateful events in D.C.

Blue Caprice premiered at this past January’s Sundance Film Festival before receiving a prestigious slot as the Opening Night selection at New Directors/New Films in March. The film opens theatrically via Sundance Selects tomorrow.

Filmmaker: How did this project come about?

Moors: Well, I co-wrote the script. I wanted something I could do quickly and I wanted to do something for little money. I was looking through books and magazines, trying to find a subject, when I came across this story. Just reading about it, you could tell their was a great tragedy behind what had taken place. I had been living in the States for 15 years but for some reason I wasn’t there in 2001, 2002, 2003, when this happened. I heard about it through friends and through the news media. I remember thinking about it a lot at the time, but it wasn’t until later that it became something I’d like to do.

Filmmaker: Was it difficult to put together at the packaging and financing stage? Was it a long process or did it come together serendipitously somehow?

Moors: I hope I didn’t use all my movie god luck in this one because it came together pretty organically and painlessly. As I said, it all started because I wanted to make a very small, intimate film. Originally this was a film I was going to make with trusted friends, you know, my d.p. friend, another friend, etc. These days you can make good films for very little money if you want. So I was set on that kind of economics and but then when we started prepping the film and writing the script, and timing was so crucial because we were planning to go within the next six months and this is where the movie gods come in because people in New York started to hear about the film and we had several investors approach us about the project. At the same time, I had sent the script to Isaiah Washington at his village and he sparked to it immediately and from that moment on the entire dynamic of the project changed. We now had a very strong and well-known actor at the center of the thing, so suddenly it was possible for it to grow a bit and become a traditional-sized indie. It all happened very organically. To go from first sitting down with my screenwriter to six months later we’re rolling is pretty amazing these days.

Filmmaker: How much research did you embark upon about the lives of John Allen Muhammad and Lee Boyd Malvo?

Moors: Well, I didn’t meet them. John Allen Muhammad is no longer with us, of course. I didn’t want to meet with Lee because from the very early stages of the film it was not my intention to make a biopic. I wanted to make a unique and distinctive interpretation of the events and for it to be somewhat more timeless and more abstract than the real thing. We did a lot of research. The first three months or so of pre-production was used for me and my screenwriter to go through all the extensive amount of court documents that exist. The medical records that the psychologists had, the U.S. Army records, we went to the scene of the crimes to walk the area and retrace the footsteps they took. It was quite a disturbing thing to do. In order to map out the chronology, we would go to the crime scene and figure out how they came in, where they parked the car, how they left. It was real investigative work that happened and we went back and tried to take a step back and have the film be about something a bit larger than just the two of them.

Lee Malvo collaborated on a book where he explains a lot of exactly what happened during those days and what his relationship was like with John. We didn’t have access to this book when we were writing and we really had to imagine what was the dynamic between the two and what their conversations were like. We were very interested in the fact that we didn’t have all the answers and the film is constructed with a lot of ellipses and gaps in the narrative. We are not sure why exactly they are doing certain things, everything is not being discussed between them and that is something that really interested me, that we have this kind of fractured structure where you do not completely understand what goes on and what is at work in their minds. I was very satisfied with that. What also really interested me was the sort of father-and-son relationship that these two men had. So we really tried to construct the script with this traditional father-and-son thing in mind and then we twisted it in a direction of the psychological terror that this young boy received.

Filmmaker: Brian O’Carroll’s lensing is really stark and memorable in your film. Can you talk a bit about your process with him in terms of what references you spoke about or how you collaborate to design the film from color to frame to lens choice?

Moors: Brian O’Carroll was the first person I sat down with to talk about the film. From the beginning the idea was to go for natural light, for a look that would be quite gloomy and grey and depopulated. We wanted to be in the kind of no man’s land visually and narratively. We used the ALEXA camera and it is very good in low-light environments. So we were able to shoot a lot at the end of the day and after the sunsets for the 40 minutes when you still have a little light and you can see things but it’s extremely bleak and there is no more sun and it is extremely gloomy. We made a point each day to try to make the day by 45 minutes before so that we could shoot extra things during that time. We organized our days to take advantage of the precious moments.

Filmmaker: Did you always have such an unusual editing style in mind or did it grow out of various frustrations and surprises in the editing?

Moors: The most difficult thing to do was the realize the violence. There was an early version of the script where we don’t even go to Washington; we ended the film when they leave Tacoma because in a sense what happens after that is well-known and has been covered by the media so we were less interested in the the end. It was included in the montage at the end but in the script it was different, it was flash forwards that revealed the killings. It took many months and many shapes before we arrived at the right combination. I told you very early on in our conversation that we put together the entire film in six months but the truth of the matter is after we finished shooting it took almost a year and a half to get the editing right, to find the right version, the right combination that I was happy with. There were many different versions, flashbacks, flash forwards, upside down, the whole editing process was quite challenge. I was extremely pleased with the way it worked out and the different layers that are in the finished process.