Back to selection

Back to selection

New Mexican Films Shine at the Zurich Film Festival

Quickly gaining stature as one of the best of Europe’s newer players on the fall festival scene, the Zurich Film Festival wrapped its ninth edition last weekend after it’s longest and most wide ranging event yet. One hundred and twenty-two films screened over the course of 11 days in Switzerland’s largest city, one which besides being a capital of world banking is among of the oldest continuous settlements in Europe, dating back over 6,400 years. The festival, run by Karl Spoerri and Nadja Schildknecht, featured its most star-studded group of guests yet, with the likes of Harvey Weinstein, Harrison Ford, Michael Haneke and Hugh Jackman being feted on the festival’s oddly green carpet with various honors, while a group of directors that would be right at home in a Cannes competition lineup, among them James Gray, Atom Egoyan, David Gordon Green, Andrew Dominik and Marc Forster, were either in town to exhibit new work or sit on one of the festival’s several juries. The four main competitions, delineated between international and German language films as well as narratives and docs, focus on first-, second- or third-time filmmakers making international, European or within the “German-speaking realm” premieres; the galas and special screenings tend to dominated by established international auteurs or films making their world premiere in Zurich. Sidebars focused on new Brazilian cinema, cinema within conflict zones and children’s films rounded out lead programmer Viviana Vezzani’s impressive selection.

Among the international narrative competition, one which included noted American titles such as Ryan Coogler’s Fruitvale Station and Peter Landesman’s Parkland, a pair of new Mexican films stood out. The top prize, awarded by Marc Forster’s jury, went to Diego Quemada-Diez’s heartrending illegal immigration drama La Juala de Oro, which in rough-hewn digital video tells the story of four South American youngsters, three boys and one girl posing as a boy (complete with a bandaged down chest), who attempt to cross the expanse of Mexico via the top of train cars in order to seek a better life in America. As we see them shaken down, tortured and frequently misled by drug cartels, police officers, couriers and Tijuana border crossing guides, the movie has a verisimilitude that the slicker and less bleak Sin Nombre doesn’t; the predicaments and tribulations these children go through are quite cruel and often brutal, with little hope for a better life in the States awaiting those who make it. That is unless you consider cleaning scraps of meat off the floor of a CAFO-fed beef processing plant in a union-busting, “right to work” state for less than minimum wage an ideal to risk your life for. A devastating rebuke to the likes of Iowa congressman Steve King, the GOP ne’er-do-well who suggested recently that most illegal immigrants crossing from Mexico were “130 pound drug smugglers with calves the size of cantaloupes”, the movie contains multitudes and demands to be seen by audiences in this country more so than in the land of neutrality, chocolate and cheese.

Aaron Fernandez’s La Hora Muertas may have a title straight out of an André Bazin essay, but it’s less severe and more engaging than its title suggests, a warm-hearted, tactile story of a pair of lonely people pushed together by unlikely circumstances. Sebastien, a teenager forced to run a rent by the hour roadside motel after his uncle falls ill, and Miranda, an attractive thirtysomething awaiting a lover who never arrives, strike up an at first peculiar bond at the nearly empty, seaside Palma Real, but as time passes the two strike up a friendship and an attraction that is handled with just the right mix of humor and emotional insight by Fernandez. Impressive lensing and thoughtful writing give this mostly weightless story some grounding, with Fernandez’s straightforward naturalism buoyed by a pair of charming performances from his leads. Together, La Hora Muertas and La Juala de Oro signal once again that Mexico, a decade after the emergence of Carlos Reygadas and amidst the sustained Hollywood success of the “three amigos” (Cuaron, Del Toro and Gonzalez-Inarritu), is a country consistently providing some of the most compelling voices in world cinema.

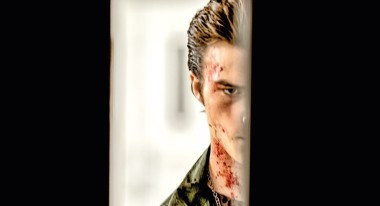

Among the 16 world premieres the festival unfurled, Tim McCann’s White Rabbit was the only American entry of note. A terse school shooter movie featuring impressive, appropriately trippy photography from Alan McIntyre Smith and, as its Jefferson Airplane/Alice in Wonderland-referencing title indicates, some rather tricked out and disturbing subjective filmmaking techniques, White Rabbit seems an odd fit for a Zurich world premiere; it would fit impressively in a number of midnight programs as the major winter and spring American fests. The movie focuses on a put-upon, backwoods Southern teenager named Harlon (The Descendants‘ underwhelming Nick Krause). Lonely and not terribly bright, obsessed with bizarre, S&M-esque comic books and generally put upon by his functioning addict father, Harlon never quite gets over shooting a pale, snow-like rabbit in his early youth. As a teen he slowly morphs into an indiscriminate killer following the demise of his fleeting relationship with a new-in-town, drug- and drink-fueled, petty thieving wild child (Britt Robertson) who finds Jesus after a near overdose. Along with the Lord and Savior she hooks up with a new, appropriately bible-thumping suitor who happens to be one of Harlon’s chief antagonizers at school. Tipping point! Guns, bullying, poor parenting (True Blood‘s Sam Trammell as Harlon’s father is the best thing in the movie), mental illness, the media; what causes this kind of thing to happen? The movie doesn’t really try to provide any answers, but its gallery of talking comic-book characters and rabbits definitely let us known that Harlon isn’t all there in the head. It’s built, like McCann’s previous fest circuit successes Revolution no. 9 and Desolation Angels, to take us into the grim inner workings of an addled mind on a self-destructive crash course and make us feel some pangs of understanding and sympathy while maintaining the veneer of a thriller. Despite a ho-hum performance from Krause, the movie manages to do just that; it’s not as elegant as Elephant or as artfully opaque as We Need to Talk About Kevin, but it’s built for maximum glide and hard to shake nonetheless.