Back to selection

Back to selection

How Jewish Is It: Best of the NYJFF

Ida

Ida Today it’s fairly easy to order films with Jewish subject matter from Eastern European countries — but think back 22 years. After the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, a number of so-called Jewish films began production in the former Soviet Union and its satellites. In 1990 the huge San Francisco Jewish Film Festival successfully tested the waters of glasnost by holding the event in Moscow.

As a result Wanda Bershen, then director of the broadcast archive at New York’s Jewish Museum, approached Richard Pena, who was at that time program director of the Film Society of Lincoln Center. In 1992 the first New York Jewish Film Festival took place as a joint collaboration between the two organizations, with Bershen at the helm. After she departed in 1998, Aviva Weintraub took over, and continues today. Since the beginning, the films have come from all over, and have included new and restored titles, narrative, experimental, and animated works.

In my foggy memory the programs in the first decade or so were more intensely focused on Jewish subjects and personalities than they are today: Judaica ruled. The five features I consider the most accomplished in this year’s fest (Jan. 8-23) can be measured on a sliding scale of Jewish identification, at least by one of the principal characters. At one end, say, the left, only the itsy-bitsiest connection to the religion or culture appears to be a requirement for a berth in the event.

In Ida, for example, a sheltered Polish novice about to take her vows discovers from an aunt she never knew that she is the sole survivor of a family brutally massacred during the Holocaust. The guilt-racked French priest at the center of The French Cardinal did in fact know that he was the child of Jewish parents, Poles who had emigrated to France and were then sent to Auschwitz; he made the decision at age 14 to convert to Catholicism. In Ana Arabia, a young journalist interviews the extended Islamic family members of a recently deceased Holocaust survivor who had also made a decision to convert, in this case to Islam, and for love.

The relationship to Judaism is more complicated in Friends From France: On one hand, two French teens go to the Soviet Union in 1979 to help oppressed refuseniks get to Israel; on the other are the refuseniks themselves, Russian Jews unable to embrace their religion and denied visas. Finally, at the far left of the scale is the documentary Amy Winehouse: The Day She Came to Dingle, half concert, half interview, which makes no reference at all to the religious tradition from which she evidently comes: It is a non-issue.

Listed in order of preference, these are my top five:

1. Ida, Pawel Pawlikowski, Poland

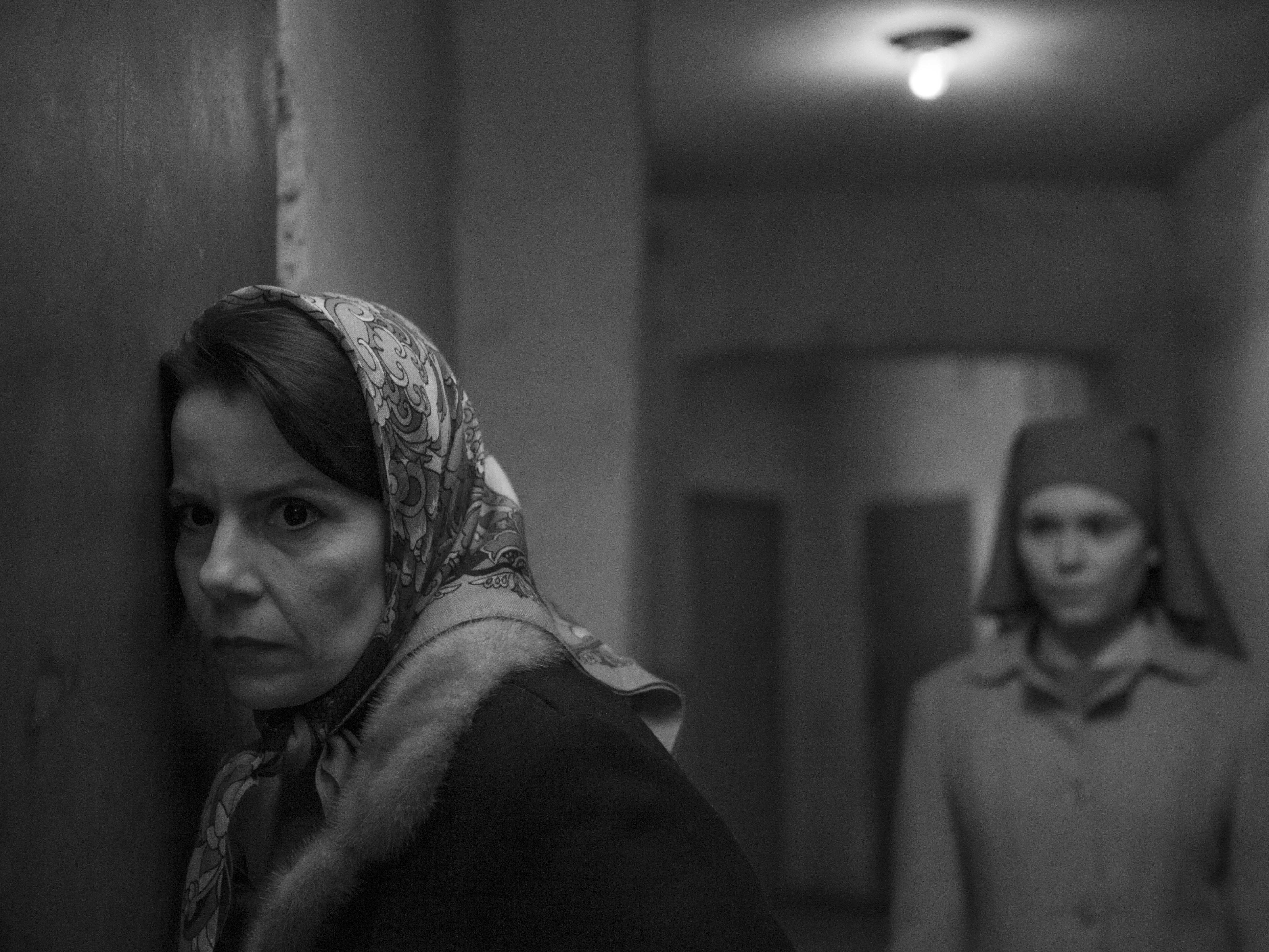

You can find one significant similarity between this first film directed in Pawlikowski’s native Poland and his breakout picture, My Summer of Love, shot in his adopted U.K. The latter, in gorgeous color, put the director (and actress Emily Blunt) on the world-cinema map for its sharp observation of two very opposite teen females and the strong effect they have on each other, which becomes sexual. In the existential Ida (see photo above, with Agata Kulesza as Wanda and Agata Trzebuchowska as Ida), with a gorgeous monochromatic austerity emblematic of the devout Catholicism and hardline Communism that were the rule in Poland in the early ‘60s, we again have two females, also worlds apart, but in almost every other way it diverges completely from My Summer of Love.

One woman is young Anna (Agata Trzebuchowska), as unworldly as they come, who grew up in an orphanage and moved directly into a convent, where she is scheduled to take her vows. The unflattering neutral color of her uniform hides a sensuous beauty that she is completely unaware of — she has beautiful long hair when she releases it. She also has no knowledge of her origins: Her real name is Ida Lebenstern, the only member of her immediate family to survive the war.

The other is her mother’s sister, Wanda (Agata Kulesza), who ignored the child’s existence until Ida’s Mother Superior pushed the two together. Wanda, her hair pulled tight, her face revealing too many late nights, has been almost pathologically worldly. She became a brutal Party judge (“Red Wanda”), then, as her status waned, began to drink and screw her life away. When Anna asks Wanda to take her to the spot where a greedy farmer buried her parents, Wanda takes charge and forces the man to take them there. No matter how far apart the women are in every possible way, the hours they spend together watching him dig up their remains bind them for the most intimate, if harrowing, of shared experiences.

Of course Wanda can see in Anna the kind of person she might have become had she retained a modicum of decency. A life-changing decision ensues. For her part, Anna tastes a bit of Wanda’s lifestyle, though a cleaner version, after meeting a magnetic alto sax player (Dawid Ogrodnik), who had become smitten with her in the bar of a sad Commie-era hotel. Any illusions she might have had about the other side are quickly quelled when she, well, lets her hair down and finds in him the kind of innocence that for her is now irrecuperable; she too makes a decision that casts her life course in stone.

2. The Jewish Cardinal (Le Metis de Dieu), Ilan Duran Cohen, France

Freud would have had a field day with this real-life man’s father fetish.

Frenchman Jean-Marie Lustiger (Laurent Lucas), ne Aaron Lustiger, is very attached to his papa, a Jew who had emigrated from Poland to France before the war only to be sent to Auschwitz. The father hates Poles with a vengeance, more than he detests Germans, and despises Pope John Paul II (a terrific, understated Aurelien Recoin) for saying mass at the camp where his wife had been gassed. Lustiger fils became conflicted after converting to Catholicism as a teen: He desired his dad’s approval but it was not coming. He rose rapidly in the church hierarchy and became not only a cardinal but, ironically, a close adviser and friend to the Polish pope.

Lustiger was undiplomatic, unable to compromise; he threw tantrums. His new intimate and supporter was subdued, and knew how to disarm him quietly. The tension inside him began to boil over on a visit to Auschwitz, when he froze, unable to recite either the Lord’s Prayer or the Kaddish. His efforts to identify himself as both Jew and Catholic were failing. When the pope, worried more about eliminating Communism in Poland than pleasing worldwide Jewry after an order of nuns established a convent at the camp, refused to enforce an edict that Lustiger and a group of religious leaders had negotiated to evacuate the convent, the cardinal shouted at him near the pontiff’s outdoor swimming pool, “I’m tired of being the court Jew!” He was genuinely ready to step down, but his second daddy quietly escorted him inside and signed the document.

You might think, Who the hell cares about one man’s problem choosing between faiths? Here the conflict is played out beautifully, a balanced yin-yang between Lustiger and the Holy Father. Otherwise this might just be an ordinary movie made for TV, with the usual abundance of close-ups. Though the others in the pope’s entourage watch Lustiger’s tirades with a mixture of horror and worry, the pontiff refuses to lose control. He is attracted to the man’s wild inflexibility that is so bound up with his intelligence, curiosity, and infectious energy. And wisely, the cardinal knows how to build on the pope’s cues, like using the mass media to spread the Church’s teachings to a younger audience.

In one of the more shocking scenes, the kind young Polish priest who takes care of them during their visit to Auschwitz says he did not learn of the Holocaust in school; references were deleted from all textbooks. Others tried to deter Lustiger from correcting him. The film stresses how dogma and protocol are of paramount importance in the Church. It must not have been easy for Lustiger to work within these boundaries.

3. Amy Winehouse: The Day She Came To Dingle, Maurice Linnane, U.K.

This one-hour BBC Four production doesn’t have a Jewish angle, except on background we know that Winehouse came from a Jewish family. (For anyone who cares, I think the yiddishe punim and several mentions in the film’s interview of “standing in my brother’s doorway” listening to music that knocked her out as a young teen are clues. The latter is to me a generalization rooted in truth about the proxemics of male and female siblings in a Jewish household: The younger sister knows the boundaries, and the older brother feels obliged to feel annoyed and enforce them.)

This is Winehouse on the cusp of superstardom: a concert for 85 in 2006, just after the release of her breakthrough album Back to Black, in the tiny church of St. James in the remote Irish fishing village of Dingle, County Kerry, often described as “the edge of the world.” In 2012, a year after her untimely death, BBC Four paid tribute to her by intercutting that six-song set with an on-site interview by Irish music series Other Voices’ then-presenter John Kelly, clips of artists Winehouse named as influences, and reflective commentary by people involved with her one-day journey, from bass player Dale Davies (only he and a guitarist accompanied her for this pared-down, almost pure performance) to taxi driver Paddy Kennedy to Reverend Mairt Hainey.

The only decorations on-stage are colored spots, which never interfere with her astounding renditions that include Love Is a Losing Game, Me and Mr. Jones, Back to Black, and Rehab. In an inspired editing choice, Winehouse’s version of the down-and-dirty You Know I’m No Good follows her comparison of purity of faith with love of music, with gospel legend Mahalia Jackson as her example. She tells Kelly her interests were the reverse of the usual: She began with jazz and hip-hop, then moved to gospel and Motown. She quickly dismisses Ella Fitzgerald: Sarah Vaughan is more her style (“she has a reed instrument”). Other artists who earn her adulation include Dinah Washington and the Shangri-las (“then a miracle: a boy,” she giggles, fessing up to her love of melodrama in pop lyrics).

The six numbers had not been heard over and over again in 2006; they were still fresh at the time of this intimate concert. “Artists sense something special here,” says Other Voices’ director Philip King, and the evidence is right before you. Winehouse’s held notes, her bluesy modulations, her range: They are difficult to take in, especially via a close-up camera, coming from this tiny, needle-thin frame attired in tight black pants and top, her head topped with her trademark comb-up. She may sing about rehab, but the 23-year-old still has girlish qualities on-stage, like a curtsy, a wide toothy smile, and a shy “thank you.” During the interview, she describes singers and songs she adores as amazing and “mas-sive:” British teen talk.

This valuable documentary shows us a great artist at work, and perhaps offers some understanding of what made her tick and what might have caused her to unspool. In Reverent Hainey’s opinion, “Great art came from her on the edge, but it shouldn’t have to stay on the edge.” Perhaps Winehouse couldn’t pull herself back, but, sadly, that meant the loss of a great artist and a lot of great art.

4. Ana Arabia, Amos Gitai, Israel/France

This is no doubt Gitai at his most gimmicky, but it is also Gitai at his finest. A continuous 81-minute Steadicam take captures the daily lives and oral histories of a small extended clan and a few neighbors in an tiny enclave in Jaffa, the old part of Tel Aviv. The spot has changed little since the 1948 Israeli War of Independence marked the sudden separation of Jews and Arab Muslims in British Palestine.

The family is Muslim with a few Jewish converts. Listening eagerly to their stories is young, attractive Jewish Israeli journalist Yael (Yuval Scharf), who is researching a story on the recently deceased matriarch, Sima, nicknamed Ana Arabia. Born Hanna Klibanov, Sima was a Jewish Holocaust survivor who came to Israel and converted to Islam in order to marry a Muslim construction worker, Yussuf (Yussuf Abu Warda), who is at the center of the film. Eschewing conventional editing, Gitai opts for a unifying strategy that, in theory, gives equal weight to all characters. He tosses out the politics of division by recreating, at least in spirit, a sense of the pre-1948 Palestine in which Jews and Arabs often lived and worked side by side.

The film begins with the camera aimed at sawed-off tree branches in the air, and ends with it moving up, up, up past the surrounding neighborhood and more distant high rises to a view of only clouds and sky. In between it glides through a series of courtyards, paths, gardens and buildings that have probably not changed much since the war. Ambling up to different residents with personal questions, Yael might be seen as intrusive, but the residents and she feel comfortable with one another. (She plays the part of messenger, an excuse for each of the residents to tell their stories.)

One man is Yussuf’s younger son, an easygoing ex-fisherman fallen on hard times who advertises vegetables with his truck’s speakers; One woman is the old man’s older daughter, who finds in gardening the love usually reserved for a man; another is his former daughter-in-law, a Jewish convert and now a widow. All have fascinating tales of earlier times but appear resigned to life in this place, an oasis or a prison depending on your point-of-view.

Yussuf explains how Jews and Arabs both tried to thwart his and Sima’s courtship. The Jewish daughter-in-law speaks about the difficulty of trying to make her mixed marriage succeed, how even her own children turned against her, but after the death of her husband, Yussuf’s family took her in. With little in the way of material goods, their warmth and generosity is palpable.

5. Friends From France (Les Interdits), Anne Weil & Philippe Kotlarski, France/Germany/Canada/Russia

What ignites this otherwise enervated set-up between free Jewish teens visiting from France and oppressed Jews in the Soviet Union who are recipients of their token gifts and expressions of Zionist goodwill is a small hidden notebook worthy of Primo Levi. Viktor (Vladimir Fridman) is a beaten-down physicist in Odessa who has tucked away a record of his prison experiences solely for the eyes of his beloved wife, who made it to Israel while he did not. Jewish team leader David (Alexandre Chacon) wants to publish it for the good of all of the Russian Jews, while 18-year-old French volunteer Jerome (Jeremie Lippmann) commits to helping the older man fulfill his wish.

Jerome’s beautiful cousin Carole (Soko) also becomes his lover on the trip. At one point, she says that she would like to write a newspaper article about their experiences in the USSR, the first hint of what is to come. Jerome has been under the watchful eye of the KGB since they first arrived, probably because of his Russian surname, so he becomes a natural smuggling suspect for Viktor’s record. Carole, however, is not. Our eyes are on another member of their group, but events move in an unexpected direction.

The film questions the motives of several of the Jews on both the French and Soviet sides: Jerome has tagged along in the first place only because of his feelings for Carole; David confides to Jerome that many of the Russians are not really keen on emigrating to Israel but to the U.S.; Carole clearly has professional aspirations that match or supersede her altruistic nature; and a young beautiful Russian wants to marry Jerome chiefly as a means to get out.

The least stagey scenes are those of young Russians putting on parties and satirical skits about their plight as hostages in their own country, especially their daring public stagings of fake KGB arrests. The 10-year flash-forward at the end feels forced. All of the principals are in Israel, coupled differently than before but with a happy ending that’s hard to go with.