Back to selection

Back to selection

Dancing in Tungsten Light: DP Rob Hardy on Ex Machina

Ex Machina

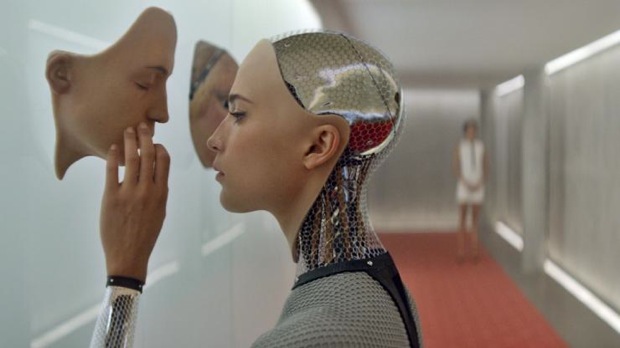

Ex Machina In writer/director Alex Garland’s Ex Machina, a coder (Domhnall Gleeson) for a Google-esque tech giant is summoned to the remote compound of the company’s CEO (Oscar Isaac) in order to test his latest creation – an alluring humanoid robot named Ava (Alicia Vikander). Gleeson’s mission is to conduct a Turing test – a series of questions designed to determine if a form of artificial intelligence has achieved human consciousness.

Ex Machina cinematographer Rob Hardy was faced with a similar mission – convincing audiences of Ava’s humanity despite her obvious mechanical parts. Hardy talked to Filmmaker about using everything from lens choices to 2nd unit landscapes to fulfill that objective.

Filmmaker: Alex Garland’s script was originally set in Alaska. How did you end up shooting the film’s non-soundstage portions in Norway?

Hardy: Norway is actually one of the most expensive countries in Europe to shoot in. I don’t know how [the production] managed to do that on the budget we had, but it was extraordinary. [Production] did a lot of preliminary scouting prior to even prep. They looked everywhere. They went to Spain, parts of Europe and to Alaska as well. They even went up to Scotland. In the end, Norway offered up a landscape that was very surreal. The further north you go, the more surreal it becomes and you find these huge walls of rock that extend up. There were times when we were in helicopters scouting for glaciers and we’d fly over a fjord and you’d look down and see what you thought was a tiny little boat and then realize it was a passenger cruise liner. It just became an epic landscape that was such an integral part of the story. Whenever we shot exterior landscapes, my remit to the 2nd unit DP Stuart Howell was to imagine that you’re Ava and imagine you are viewing this landscape for the first time, so it almost becomes an alien landscape in a way.

Filmmaker: In addition to those Norwegian landscapes, the aboveground level of Nathan’s isolated retreat is also striking.

Hardy: We were fortunate enough to come across a Norwegian businessman who’d just had his house built by this quite well known Norwegian architect, but he had yet to move in. This extraordinary house was essentially built onto the side of a rock face and the rock — as you see in the movie — protrudes into the living room. It was a no-brainer for us [to use it]. Originally as scripted, Nathan’s house was this almost Bond villain-like home in the middle of this valley that was supposed to really stand out [from its surroundings]. But the more we scouted, the more we realized that it was much more interesting to have something that was a little bit more hidden and part of the landscape. In addition to that house, there was a hotel called the Juvet Landscape Hotel which wasn’t far from where the house was. Again, it was sort of built into the landscape — fused into the woodlands and right by this amazing river that ran down from the mountains.

Filmmaker: Did you approach shooting the aboveground and belowground levels of Nathan’s house differently?

Hardy: My thinking was that above and belowground should elicit the same feeling. I didn’t want to differentiate them in terms of the way I lit them or the way I shot them. They are different in their own specific way – one is very open and the other is very enclosed – but the key thing was to make sure they linked and that the film was visually cohesive as a whole. So aboveground and belowground I really only used tungsten light, which gives it a sort of gauziness.

Filmmaker: A significant amount of the belowground level – which encompasses Nathan’s workspaces, the sleeping quarters and Ava’s room where the Turing test is performed – is lit by units built directly into the set. What was the advantage to lighting that way?

Hardy: I’m always an advocate of shooting in a 360-degree environment and building lights into the set often allowed me to do that. It helps not only with the way you shoot, but also in the way in which the actors can perform. They can immerse themselves into an environment and it just makes it that much more real. Also, with any set, I always want to put a roof on it. I don’t really understand why there’s never a roof on a set. (laughs) Originally when the sets for Pinewood Studios were first designed just prior to me coming on to the show, they were designed to hold fluorescent tubes. I didn’t quite understand this concept that fluorescent tubes equal sci-fi. Instead, I went back to the idea of using tungsten and I had my gaffer Lee Walters spend two weeks fixing all three sets with these battens with 40-watt tungsten bulbs on them that we could control. Everything went back to a dimmer board, so whenever you looked in any direction you could adjust the intensity of the light and also the color of the light and that would create environments that would suit the mood of the scene. From a practical point of view, it meant that we could shoot very quickly. It also gave me the soft, gauzy feel that I was after and the only downside is that the bulbs get really fucking hot. We were shooting at Pinewood on a rare occasion where it was a hot British summer. Alicia was in this gray mesh catsuit while everybody on the crew was wearing shorts on set. It was just boiling hot, but it added to the tension I suppose.

Filmmaker: If you were just after a tungsten color temperature, you could’ve used something like tungsten balanced Kino bulbs in the fluorescent fixtures the set was originally designed for. What was the attraction of using a vast number of small bulbs as opposed to longer Kino tubes?

Hardy: I think smaller units have a softer feel. When you have a numerous amount of them and you put them through enough diffusion, they tend to give a certain kind of light. I don’t want to feel like I read the lights. I want it to feel like it emanates from the frame rather than it being placed there. I liken it to the difference between Vermeer or Rembrandt. With Vermeer, you look at those paintings and you can see the source of the light and there’s nothing wrong with that. They’re incredible paintings. However, if you look at Rembrandts, you can’t really tell where the source is, but it has an amazing mood and I find it much more subtle and much more interesting, and for me personally it elicits much more emotion. It doesn’t draw attention to itself in a way that a very sourcy light does.

Filmmaker: Did you have to change out bulbs to red units for when you entered the “power failure” scenes or were they already included in those tungsten battens?

Hardy: We built them in, which was another advantage of using smaller units. We experimented for weeks with different styles and different ways of introducing the red during prep until we found the ones that we felt were right for certain moments in the story. At different moments, the red can mean an element of danger or it can be almost absurd, as in when Nathan descends into his disco dance.

Filmmaker: Since you’ve brought up Nathan’s extended boogie to Oliver Cheatham’s “Get Down Saturday Night,” talk a little bit about shooting that sequence.

Hardy: It was just about the most fun thing I’ve ever shot. I just have to highlight that we had such fun shooting this movie. Alex is a genius for creating a family environment. When we arrived at the dance scene — I think it was about halfway through the shoot — it was almost like having a day off. (laughs) We spent the whole day shooting that scene. There was so much more material that you don’t see. I think one of these days they should release a full version of that dance scene. It’s a short film in its own right because we shot so much [footage] of it. From a narrative standpoint, it’s just so brilliantly placed in the film and so brilliantly conceived. [The audience’s] allegiances to the characters shift and change. You never really know who to trust and sometimes you warm to a certain character and then suddenly you’ll switch and warm to somebody else. I think it was of utmost importance that Nathan had this moment.

Filmmaker: I know Alex Garland draws a little bit, but you talked earlier about preferring an environment in which you can shoot 360 degrees and have freedom. How much were your shots locked down in preproduction and how much did you determine them once you got the actors into the spaces to block out scenes?

Hardy: We storyboarded very little. We storyboarded the helicopter sequence — simply because we needed to for budgetary reasons — and the fight sequence, because purely based on the amount of time we had to shoot it, we really needed to know what we were going to do. As far as everything else is concerned, we had the luxury of having nine or ten weeks prep at Pinewood prior to shooting. Every morning we’d go in and I’d sit with Alex and the actors. We’d go through the script and go through certain scenes and then we’d wander down to the stages and start getting a feel for the space, even if it was being built around us. Each of the Ava sessions is a long scene and it would’ve been so easy to just let each one of them feel similar, but that was absolutely not what we wanted to do. There had to be a progression in the way in which we shot those scenes, and so each one not only was choreographed in a different way but was also shot in a different way. I’m talking about subtle increments, really, but that time spent blocking those scenes prior to shooting was invaluable. In essence, that was our storyboarding. It was storyboarding without ever drawing a thing, and that way I could then instill a distinct personality or an emotional intent through the photography of each of those scenes.

Filmmaker: Did Alex have any particular references for you?

Hardy: A lot of it just came from the script. What’s so remarkable about Alex’s writing is that you read it and it elicits such a strong vision. So in a strange way we had very few references. There were perhaps two that came up in conversation simply because we were trying to demonstrate an idea. One of them was the photographer Saul Leiter, the 1950s New York street photographer. He shot a lot of things through shop windows and a lot of his work was based on reflections. His color work is just extraordinary. The other person was [Kazimir] Malevich, who is a Russian painter who worked with abstract geometric shapes and forms. For me, that informed very much the way in which I would light the set and control those lines and those reflections. I could make frames within frames and position Ava and Caleb in a way that would be not just visually pleasing but also serve the feelings we were trying to elicit. Two films that we did talk about were [Andrei] Tarkovsky’s Stalker, simply because we were being self-indulgent and it’s a beautiful movie, and also John Carpenter’s The Thing. I always come back to The Thing, just simply because of its sense of creeping dread and the fact that you never know who’s who. That was a good thing to have in our back pocket with Ex Machina, because [the audience’s] allegiance changes between the characters.

Filmmaker: There’s a quote you gave a few years back. To paraphrase a bit: “Choosing a lens is like choosing who your best friend is going to be for the next few weeks.” Why was a set of Cooke Xtal Express anamorphic lenses your best friend for Ex Machina?

Hardy: I think it’s just a feeling, which is why I think the testing process is so important. When I look through the finder, I’m looking for a feeling and it’s just a question of finding it. With Ex Machina, it presented itself with this combination of the [Sony] F65 and these old Xtal Express lenses. I used them on a short film I shot and directed some years ago and I used them maybe once or twice on a couple of commercials, but that was about it really. But when I was shooting tests for Ex Machina, suddenly [the Cooke Xtals] were like, “Here we are. We’re going to be part of your family.”

Filmmaker: What makes the look of those particular Cookes unique?

Hardy: What’s great about those specific lenses is the imperfections. The Cooke Xtal Express lenses were all hand built, so each set is different. So a 32mm from set A would be different from a 32mm from set B. What we did was bring together all the sets we could possibly get at Panavision in London, which is where most of them are kept. Jennie Paddon, my first assistant, basically ran through all the sets and picked the lenses that she felt had those subtle elements that I wanted. Then I would go in and look at the choices. Eventually we boiled it down to what we started calling The Tuco Set. I likened the way Jennie broke those sets down to the way in which Tuco [Eli Wallach] in the film The Good, The Bad and the Ugly goes into the gun shop. Instead of buying a single gun, he takes out several guns and pulls them apart and creates a new gun out of pieces from all of them. That’s essentially what Jennie did, so they’ve become known as The Tuco Set. I think when you use The Tuco Set, it’s not like you’re going to say, “Well, I need a 32mm because it’s simply wider.” It’s more like, “I need a 32mm because that’s the feeling I’m after.” The Xtals offer that as opposed to something like a much more clinical and precise lens, like the Zeiss lenses for example, where you know that you’ve got uniformity between the lenses. I didn’t want that uniformity on this film.

Filmmaker: Many of the cinematographers I’ve interviewed who have used the Sony F65 or F55 have done so in part because they were working on Sony-funded films. That is not the case with Ex Machina. You tested the F65 against the ALEXA and Red Epic. What about that camera swayed you?

Hardy: I found that with the other cameras — specifically with the ALEXA — they negated my lens choice in a way. It didn’t destroy it, but it dispelled some of the subtleties that the lenses had. I’m not saying that one camera is better than the other. What I’m saying is that for Ex Machina, the F65 was a no brainer. It gave us the right palette for the film. The other cameras simply couldn’t offer that combination of reading the lenses, reading the skin tones and reading the soul of someone, which I often find is missing when shooting digitally. It’s a subtle thing I’m talking about and most audiences will probably barely notice it, but the subconscious ways in which you present something actually accumulates to create an overall feeling, and that’s what I’m looking for when I chose the tools that I use.

Filmmaker: Rather than placing green material or tracking marks on portions of actress Alicia Vikander’s wardrobe in order to more easily create Ava’s visibly mechanical parts in post, you shot the scenes as if this wasn’t an effects movie. Was that a difficult sell to the VFX folks?

Hardy: [Visual effects supervisor] Andrew [Whitehurst] understood very quickly the importance of photographing the film in a way which served the narrative emotionally. In other words, the audience has to feel a humanity toward Ava. For that reason, we all decided that we wanted to photograph the film in a way that was never restricted by the idea of effects or greenscreen or tracking marks or anything like that. We wanted it to feel like a human story. Andrew very quickly was like, “You want to use old fucked up anamorphics? Great. You want to shoot with lots of reflections and move the camera around all the time? Great.” (laughs) I’ve never come across that with any VFX supervisors prior to this point. We were all blown away by the work that [the effects companies] did. You feel like you’re in the room with Ava. You really believe it. I think that’s so important to a story like this. Otherwise, it’s just going to end up looking like every other effects movie.

Matt Mulcahey writes about movies and interviews filmmakers on his blog Deep Fried Movies.