Back to selection

Back to selection

Cult, Underground and Independent in Flux: The Oak Cliff Film Festival

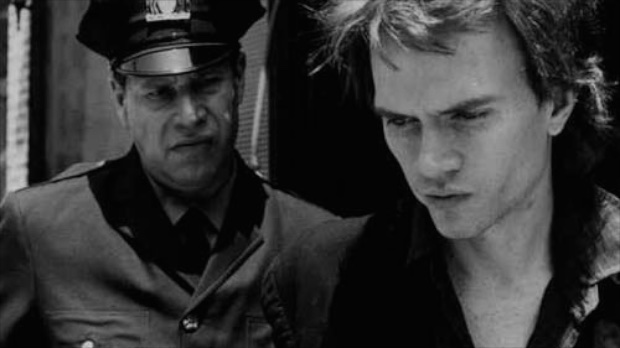

Police State, by Nick Zedd

Police State, by Nick Zedd I arrived in Dallas for the Oak Cliff Film Festival and got picked up in a car along with Nick Zedd, the storied New York underground filmmaker who relocated to Mexico several years back. The first thing Zedd, whose own work is marked by a tongue-in-cheek fetish for violence, asked our driver about was the Kennedy assassination. Over the next few days, it became clear that Dallas, with its own mythology of Oswald conspiracy theories and Bonnie and Clyde’s, grave sites was the perfect city for a festival that had a thread of cult films and figures running through its programming.

Back in 1985, Zedd coined the term the “Cinema of Transgression” to describe the campy movies full of shocking sex and violence that he and other artists like Lydia Lunch, Richard Kern, and Kembra Pfahler were making on the Lower East Side. They were scrappy movies shot on 16mm often with pornographic punchlines. In Thrust in Me (1985), a short Zedd co-directed with Kern, the film climaxes with a man (played by Zedd) face-fucking a recently deceased woman (also played by Zedd). In Police State, which Zedd made two years later, he’s tortured by the cops in an interrogation room. It’s implied Zedd’s character is dismembered with garden sheers, and at the end while screaming in pain, he chooses to shoot the cop in the head instead of killing himself to relieve his anguish. Almost 20 years later, the commentary on police brutality is no less relevant. And Zedd’s work still makes people uncomfortable. At intermission during the festival’s retrospective of his films, which included both Thrust in Me and Police State, a woman told me she had to leave.

Zedd still has the same red chin-length reddish hair and piecey bangs that he always had. He still wears the skinny black pants and glam looks that he always did. But New York has changed. So has independent film, and so has the way loyal cult followings are accrued. For better or for worse, there aren’t public access TV shows and fanzines anymore. The way independent media circulates has changed over time, a reality Oak Cliff’s programming made apparent by including documentaries about an Oklahoma prank call cassette tape, Calls to Okies: The Park Grubbs Story; a Michigan public access TV show, 20 Years of Madness; and the Utah-based story of Trent Harris’s “Beaver Trilogy,” Beaver Trilogy IV. In each of these stories, the circulation of this kind of off-beat material was regional in a way it isn’t today with niche Tumblr and Vine phenomenons.

Zedd recalled a free-form TV show he used to watch as a teenager growing up in Maryland on Channel 20 called Turn On. “It was the only counterculture at the time on TV, at least locally,” he explained. “They had bands play. They had Captain Beefheart on there and Alice Cooper before he was famous.” As a teenager he even tried to get his films on the show. At 15, he went down to the Channel 20 station. “I met the programming director who said just set your projectors here in the office, and we just started projecting movies on the wall,” said Zedd. He didn’t get to meet the host of Turn On Barry Richards, but he did see the Channel 20 mascot, Captain 20, walking around in his space suit. “They didn’t show our films but I felt like this is the big time, right?”

Years later Zedd would get his own TV show with a cult following. In 2004, Zedd started making a series with his then-girlfriend, performer and open-mic personality Reverend Jen, called The Adventures of Electra Elf, which ran for 20 episodes and aired across Manhattan and Brooklyn. But it wasn’t from TV that Zedd first found an audience. In the ’80s, he started showing his movies around the Lower East Side at bars and venues where bands played. John Waters came to an early screening and became a fan. Zedd also drew attention to his work by hacking mainstream media. He got outlets like The Village Voice to pay attention to his films by first writing about them himself under a pseudonym. From 1984-1990, he authored a publication (which he initially photocopied in the Voice office) called The Underground Film Bulletin, where he’d write about the scene of filmmakers around him — all written by Zedd but each article penned under a different name. It was in the Bulletin that he published “The Cinema of Transgression Manifesto,” by “Orion Jericho.”

Opening night at Oak Cliff Film Festival, one of the programmers on-stage introducing the weekend’s events explained that they thought the scrappy filmmaking of Zedd’s era, not just his Cinema of Transgression but also the larger No Wave movement going on at the same time, was a good analogy for how today’s filmmakers are working extremely resourcefully with lower-than-low-budgets. Oak Cliff opened with Sean Baker’s Tangerine, a comedy portraying the antics of two trans sex workers on Christmas Eve in West Hollywood and which was entirely shot on iPhone 5S. Thee festival closed with Zachary Treitz’s Men Go To Battle, a post-mumblecore Civil War flick which, while the camera used didn’t grab headlines, was equally impressive in terms of making something undeniably cinematic on a micro-budget. Both films are stand-outs from this year’s festival circuit and were prime choices to bookend the weekend, but this analogy the programmers were making between then and now was also instructive in demonstrating the way today’s filmmakers are working in a vacuum of clear distinctions like mainstream and counterculture, and independent and studio movies.

The aim of scrappy filmmaking today seems to be to look as much the opposite of scrappy as possible, and digital tools make that goal within reach. Films like Tangerine and Men Go To Battle are made with hopes of striving beyond their budgets. They’re made for the festival apparatus which can catapult smart small films to bigger audiences. They are made, to some degree, to be accessible to a wide swath of people. Both films make experiences very specific to a certain place or time relatable to a lot of different kinds of people. While Tangerine wears its intentions to do just this on its sleeve, going to lengths to universalize its characters; unique experiences through its sitcom tropes, indeed both are independent films that in another time, when there was more room for medium-budget films, might have been able to have been pitched to a studio exec.

Regional festivals are often just a random grab-bag of films you’ve already seen elsewhere, but Oak Cliff curated a cohesive program that was powerful in its individual selections but also in that it was more than a sum of its parts. By putting some of this year’s best indies in juxtaposition with Nick Zedd’s films in juxtaposition with documentaries about cult ephemera from the ’80s and ’90s, the programming thoughtfully considered the different ways cult, underground, and independent are in flux, and the particulars of the moment we’re having right now.