Back to selection

Back to selection

Five Women Directors Discuss their Art and Craft at the New Horizons Film Festival

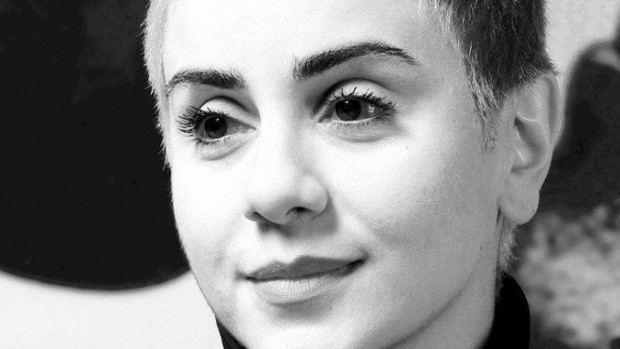

Mania Akbari

Mania Akbari On the fourth anniversary of Amy Winehouse’s death, I was watching the opening night screening of Amy at the New Horizons Film Festival in Wroclaw, Poland. Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck, another documentary about a legendary musician who died at the age of twenty-seven, was also slated in the New Horizons program. Rainer Werner Fassbinder, the controversial German filmmaker who made over 40 films before his death at thirty-seven years old, was the subject of Fassbinder, a documentary also screening in Wroclaw. The Actress, a documentary about the Polish movie star Elżbieta Czyżewska, who fled from communist Warsaw to New York and died only five years ago at age 72, premiered in the New Polish Cinema section of the festival. New Horizons Film Festival, celebrating its tenth edition, programmed over 340 films from 54 countries this year. It wasn’t until I saw Son of Saul, the Hungarian Holocaust horror film directed by László Nemes that won the Grand Prix at Cannes earlier this summer, that the cumulative effect of many of these stories hit home.

As Son of Saul‘s credits rolled, I walked out of the packed cinema and into the afternoon sun of Wroclaw, a colorful city with one of the largest and most beautiful market squares in Europe. While everyone around me enjoyed an ice cream from one of the surrounding polish “lody” shops, a miniature bronze gnome caught my eye. Hundreds of these dwarf figures dwell throughout the streets and in the corners of Wroclaw to commemorate the Orange Alternative political movement against communism in the 1980s. Each dwarf, a symbol of the movement, is unique and engaged in a different activity or position. The figurine I discovered after the Son of Saul screening was straddled atop two film reels of an old camera.

I thought of all the films I’d seen in the last week — the onscreen characters in different political and social contexts from all over the world, many having lived and died fighting against various circumstances. I thought of how stories spanning time and place have reached me in the heart of Wroclaw, in one of the largest art house cinemas in Europe. I’d seen the Lebanese singer Yasmine Hamdan perform days before at a festival after-party, having last seen her onscreen in Jim Jarmusch’s Only Lovers Left Alive, seducing two vampires with her hypnotic performance. And as I stood in front of the tiny dwarf on a camera in the heart of Wroclaw, I felt a bit like one of those vampires, mystified by the power of artistic creation. It’s not that this gnome on the camera necessarily won my affection, but that its discovery clarified the cumulative impact of all the others. A singular gnome or singer or film may be striking, but a greater sense of power is in numbers. And after a week immersed in stories told from separate lenses, I realized that this power is the juxtaposition of different filmmakers, who are, like the dwarfs of Wroclaw, all unique and yet, part of the same movement.

Below are my conversations with five filmmakers who travelled to Wroclaw from around the world to screen their films: Romanian Anca Damian, currently based in Bucharest with The Magic Mountain; Iranian Mania Akbari (London) with Life May Be; Swiss Eileen Hofer (Geneva) with Horizons; Polish Kinga Debska (Warsaw) with The Actress; and American Nancy Andrews (Maine) with The Strange Eyes of Dr. Myes.

Anca Damian, The Magic Mountain

Filmmaker: Magic Mountain is a Romanian/French/Polish co-production. How did the collaboration work?

Damian: It is majorly a Romanian production from the financial point of view, but France has been involved from the very beginning, from development of the story to the production elements. Even though my protagonist Adam Jancek Winkler lived in France most of his life, he was Polish. Besides the fact that Poland brought important financial support, it was very important for me to understand Polish culture, thinking, art, and I wanted to reference Polish animation and the polish history of cinema in the film.

Filmmaker: How else did you research the film?

Damian: I went to the Panjshir mountains in Afghanistan for three weeks. I could have read some books, seen some photos, but had I not gone to Afghanistan, I would have completely missed the story. I had done one year of research, but the reality of the story was found when I went to Afghanistan. In the end, I feel I was rewarded for doing it properly, for doing something that wasn’t easy, for doing something that scared me.

Filmmaker: You produced the movie too. Did that help drive the project forward?

Damian: My French co-producer wanted to talk about the possibility of not being able to complete the movie. I can’t think this way. The determination to complete a movie is what drives it forward. If you hesitate, nothing happens. I am a screenwriter, producer and director for all my projects. In Romania, almost all the directors are their own producers, or someone in their family. The advantage is the control over the project. But it’s the first thing I’d give up. I like producing in the early financial stage, but after the production starts, it’s really a heavy burden. Writing and directing have to go together for me. The project has to feel fully mine or otherwise, I can’t do it.

Filmmaker: The movie is premiering in Poland now at New Horizons and has already premiered in France. How do you think it will be received in Romania?

Damian: This movie is loved in France because I think it cinematographically fits the audience. Romanian audiences could be a little bit more distant. And we have so few cinemas, so though it will be distributed in Romania, I don’t have big expectations. An animated feature is not so commercial.

Filmmaker: Will the film play in New York?

Damian: We had a world premiere in the Czech Republic at Karlovy Vary so we had to pass on Tribeca. But we hope the film will play in the New York Film Festival this autumn. We also have an English version, voiced by Jean-Marc Barr, which makes sense if the movie is distributed in the United States.

Filmmaker: How did you get into animation?

Damian: It wasn’t a decision to do animation. It was a natural step. I was eighteen when I went to film school, but they said I was too young to have something to say as a filmmaker. So I became a d.p. I wanted to tell my own stories though, so I started making documentaries about art. When my son was small, I couldn’t really engage in bigger projects. Being a mother really did affect me, in terms of my profession. Half of my brain was focused on him, but once he was 12 or 14, I felt free to think more about my projects. I started thinking about new ways of storytelling, and animation was natural for me because I was a d.p. and did visual arts.

Filmmaker: What has changed since your days as a cinematographer?

Damian: I’ve been a d.p. for two Romanian feature films. I’m the only Romanian woman to have been a d.p. The industry is male constructed, as you know. With animation, I’m able to tell the stories I want to tell, and in a way, I’m opening the doors. It is a very good creative moment now in Romania that can’t be explained logically. Movies are starting to diversify beyond Romanian New Wave style, which was inspired mostly by Godard and French New Wave. After Cristi Puiu’s The Death of Mr. Lazarescu won the Un Certain Regard award at Cannes in 2005 and [Cristian] Mungiu’s 4 Months, 3 Weeks, and 2 Days won the Palme d’Or at Cannes in 2007, everyone starting making movies in that style. Now it’s changing, and I think animation has started to grow in Romania because of my movies. I’m enjoying it.

Mania Akbari, Life May Be

Filmmaker: Why did you flee Iran?

Akbari: The path of art is unpredictable, and my art is not separated from my life and myself. My land, Iran, is part of me, but throughout history, governments have fought with artists, this is nothing new. I never wanted to leave Iran, and I never imagined that one day I would not be able to return. On one occasion I travelled to a film festival, but before my return I realized the government had created a new profile for me and had announced through media channels that Mania Akbari had left Iran since she was HIV positive and a lesbian. At this point I realized I could never return. The government created a painful game that finished everything for me in one moment: my past, my memories, my deep connection to my history and so many other relationships. It was like a death.

Filmmaker: Why did they go after you?

Akbari: After my first film 20 Fingers, the relationship was never peaceful — it was like that cartoon of Tom and Jerry, a game of cat and mouse between the government and me. The government knows that religion and art are two opposing things. In countries with strict religious rules, two things are very difficult. One is to be a woman and the other one is to be a woman who wants to build something, to create something. Even so, I didn’t want to leave Iran. I feel that an artist should always stay within the country in which he knows. However, I also deeply believe that an artist should let things happen and build on the relation to things as they come.

Filmmaker: When did your desire to create begin?

Akbari: I come from a family in which there were no artists. My father was a physicist, my mother was a chemist, and they were teaching. The mystery of art is to create a question but not to provide answers. Growing up in Iran made me want to create those questions.

Filmmaker: In the two years you’ve spent living in London, how have you changed?

Akbari: Living in exile changes you a lot. Many important artists in history were living in exile or relocating from one place to another. Once you go from one place to another, you are a traveller carrying your past in your backpack. Everything changes; everything is different. The change of place is accompanied by many other external changes, of architecture, even smell, color and form. Each of these external changes causes internal changes too. Artists are particularly sensitive to the relationship between these internal and external changes.

Filmmaker: Life May Be is an unedited exchange between you and Irish filmmaker and critic Mark Cousins. What initiated this conversation?

Akbari: I needed dialogue. In today’s times, we are so lonely because there is too little dialogue. I don’t mean daily conversations, but real human-to-human connection, a dialogue that is about opening yourself up. I believe this is what humanity today lacks because we fear opening up, even though, in the end, there are no secrets so there’s nothing to fear. Once you share something you wanted to hide, you realize how simple it is. I’ve met a lot of women who’ve said I should make a movie about how difficult their lives have been. I’ve realized that the stories are all the same. In the end, people share the same pains in every day life. There are countless women who have breast cancer, but when I speak about my own breast cancer openly, so many others also realize that it’s something possible to speak about. Today, we need deep and creative conversations.

Filmmaker: Do some cultures encourage honest dialogue more than others?

Akbari: I don’t think it’s a matter of culture. All governments want to rule the world, and they give people certain values, which the people believe. This isn’t just a problem of Iran. This is a problem of the whole world. Artists protest against these given values and make new ones. This is why the world needs artists. Art is a language of resistance, of fighting, a language for new thought.

Filmmaker: But can’t artists also perpetuate warped values? Hollywood?

Akbari: I have certain issues with Hollywood. Of course people need entertainment and fun, but certain movies can be very dangerous. I especially don’t like that many Hollywood movies must have a hero and that people are taught to think they need a hero. Cinema has the power to create new values, and I do not need this type of Hollywood cinema, I do not want to be directed into worshiping someone, or to be worshipped for that matter. A real artist is not looking for solutions, but for creating questions.

Filmmaker: Can you be a successful filmmaker without compromising your values?

Akbari: I’m not sure about the word “successful” — we should think about what defines success. I think if everybody connects with an artwork, you should have doubts about that work. The responsibility of an artist is not to talk with everyone in every language, but to try to understand his own language of art. I really do not understand the term “successful artist.” I think you are an artist or not. Success is just a value that society gives, based on its own notions of value and market.

Filmmaker: Will the film be shown in Iran?

Akbari: God, no! None of my films have ever been shown in Iran. My films are pushing boundaries that mean they could never be shown in a religious country like Iran. Religion is used as a tool to control and make values based on that, and cinema can be used to hypnotize, to make it easier for governments to depict their own values and ideologies. My films operate outside of this system, and of course the government is aware of this and does not want to show films that question its values.

Filmmaker: Would you even want your work shown in Iran?

Akbari: I really want all my films to be shown in Iran one day. However unlikely that is, I am still hopeful. Everything is possible.

Eileen Hofer, Horizons

Filmmaker: When did you start making films?

Hofer: I worked in public relations for film festivals for five years after I graduated from university. I started doing interviews while travelling to the festivals, and I’d publish the interviews in the Swiss news. After I spent so much time meeting filmmakers, I thought to give it a try myself. I’d always written stories, but had kept them hidden. For my first short film, I got a little amount of money and went to a small village in the mountains of Turkey — almost every person in the village ended up in the movie. It was full of mistakes. I didn’t even know how to say “action” when we started. But the film premiered at Locarno, and then it travelled to more than 80 countries.

Filmmaker: Why did you choose to shoot in Turkey?

Hofer: I’m from Geneva but my mother is half-Turkish, half-Lebanese. I think part of the reason I went to Turkey to shoot my first movie was because of my roots (the title of the film is Roots), which is the same reason why I shot my second short film in Lebanon. The third short film I made was about immigrants, shot in Switzerland.

Filmmaker: Horizons is your second feature film. Had you been to Cuba before you went to shoot the film?

Hofer: No, but I always wanted to go to study at San Antonio de Los Baños, which is a very famous film school, but very expensive for foreigners and also hard to get in to for locals. Later, a friend told me about Alicia Alonso and we thought to go to Cuba together to do a project, and the movie basically started from there. In the end, we went to Cuba three times, but only twice with the camera.

Filmmaker: Alicia Alonso is Cuba’s famous ballet dancer who cofounded the national ballet school financed by Fidel Castro in the 1960s. Politically, how does the school function today?

Hofer: For me, the ballet is a parallel to the country in a way. The island is a closed world and the ballet is a closed world too. Fidel and now Raúl Castro ruled the Island and Alicia Alonso, a close friend, ruled the ballet in a similar way. Just as it’s difficult to get into the ballet, it’s very difficult to enter the island, especially to make a film. While we were shooting, there were spies following us, not too much, but we noticed them.

Filmmaker: Has the Cuban government seen and responded to the film?

Hofer: We haven’t screened in Cuba, but apparently they’ve seen the movie and are very happy with it.

Filmmaker: You’ve mentioned it was difficult to gain access to Alicia. How was working with local crew and subjects?

Hofer: Culturally, it was very different. People earn just twenty dollars per month. We went through five Cuban sound engineers. One left the island, another one was a misogynist who I couldn’t work with…and I didn’t have a lot of freedom in terms of scheduling so there was a lot of improvising because people wouldn’t show up. We had a lot of tough moments in the editing room trying to piece it all together.

Filmmaker: Can you describe your filmmaking style?

Hofer: Before I started, I had only been on a set once and it felt so strict. I really hated it — the costume designer would ask about yellow socks or blue socks, but who cares when the actor is wearing boots! I don’t like changing the reality. I like using the reality I have. I wrote scripts for my three short films, but when we shot, I didn’t use them. The actors, usually non-professional locals, wouldn’t see any dialogue. I asked them to improvise because I’m most interested in the psychology of the people I shoot.

Filmmaker: How do you know who you want to shoot?

Hofer: It’s the people themselves — the stories they have to tell. Last month, I had a dinner with people from the ex-USSR — from Ukraine, Kazakhstan, Ossetia, Siberia. I came with two cameras, six microphones, a bunch of vodka, some food, and we just filmed. I’ve also shot a Syrian refugee in Bulgaria for twenty minutes and it became a short film. I just received funds to make a documentary about a mental health hospital on the boarder between Syria and Turkey. But now, I don’t think I can go because it’s really dangerous with the bombings in this area.

Filmmaker: Filmmaking meets investigative journalism?

Hofer: It’s not only investigative but also telling a human story.

Filmmaker: How do you fund your projects?

Hofer: I’ve gotten funds from the Swiss government, but I’m also doing something that no one else does, which is knocking on doors for private funds. In Switzerland, it’s not common to do this but I’m receiving part of my funding through this door.

Kinga Debska, Actress

Filmmaker: How did you come on to co-direct the film?

Debska: The project came to me when it was already almost fully funded. My co-director, Maria Konwicka, was looking for a partner but hadn’t found anyone to work with. Elżbieta Justyna Czyżewska is such an iconic figure in Poland. We call her the Polish Marilyn Monroe. When I met with Maria, I expressed interest in the project not only because of how much I love Czyżewska’s films, but also because I’m mainly working with actresses on fiction films so digging into the life of one the greatest actresses is such interesting research for me.

Filmmaker: After years of making documentaries, why are you now making mostly narrative films?

Debska: Documentaries take so much time. You make only one film every three or four years so I couldn’t afford to just live off of being a documentary filmmaker. They are also a bit binding for me because you have to think about the real life consequences of the people in the film.

Filmmaker: Did you anticipate any backlash about how you’ve portrayed Elżbieta in the film?

Debska: In Poland, there’s the tendency to speak only well of someone who has died. I didn’t want to just make a nice picture about a great Polish actress. I wanted to speak openly about her, including her alcoholism, her failures, etc. This is the only way to speak truthfully, especially about women — to include the ups and the downs.

Filmmaker: How did you familiarize yourself with Elżbieta’s life in New York?

Debska: I got a grant to live in New York for a few months, so I was able to meet the people and feel Czyżewska’s world before the crew came to shoot. Her friends were my guides in a way because I came without knowing anyone. The first month was a little hard. I was living in West Village so it was a nice community (and very expensive). It took about three months to adjust, so by the time I felt ready to stay in New York, it was time to leave.

Filmmaker: Were most of her friends eager to participate in the film?

Debska: It’s only been five years since Czyżewska died, so it’s still fresh for everyone. During one of our interviews, one of her friends said that men used her, and I have to say, most of the men from Czyżewska’s life didn’t agree to be in the film. I approached lots of her male friends — famous writers and cinematographers — but most all said no.

Filmmaker: Do you think she would have felt more free in Poland had she not been forced to flee with her American husband, journalist David Halberstam?

Debska: When she was working in Poland, she was an open-minded modern woman in the midst of a communist and completely grey world. I think she would have had a tough time if she had stayed in Poland. At the end of Czyżewska’s life, she played a lot Off-Broadway in New York. Eventually New York seemed to get used to her accent and accept her. It’s so hard to live and work in a country that’s not your cultural background. For me, as a director, the financial possibilities to make a film are in my own country. When I was living in the Czech Republic, for example, I was always treated as the Polish filmmaker and was last in line for funding.

Filmmaker: When did you live in the Czech Republic?

Debska: I went to film school in Prague. My first education is in Japanology actually. I was preparing to be a translator, but finishing it, I realized it was too boring. After studying Japanese for five years and living in Japan for one, I realized I needed more. I started doing small television and documentary projects and then went to FAMU film school in Prague. It’s a five-year program, but I was able to graduate in one because of my experience already making films.

Filmmaker: Do you like co-directing?

Debska: Frankly, co-directing is not for me. It’s too difficult to do something a little bit one way and a little bit another. I need to have the space and freedom to work alone, which I was able to have in the editing room because I basically edited the film myself. It lasted about half a year because there were so many contradicting stories.

Filmmaker: Did you ultimately arrive at the right story?

Debska: With one exception. I couldn’t get the rights to use footage from the film Anna, which was written about and for Czyżewska. She fought with the director Yurek Bogayevicz about the script, and in a heated moment, she pushed him down some stairs. He replaced her with Sally Kirkland who won a Golden Globe and an Oscar nomination for the film. Unlucky for Czyżewska…

Nancy Andrews, The Strange Eyes of Dr. Myes

Filmmaker: When were you first interested in film?

Andrews: I was interested in film from a really early age and made little animated movies on my father’s Super 8 camera. I had a hiatus though because I went to an art school where there was almost no film production, so I majored in photography and took all the film history classes I could. I was kind of like the early Soviet filmmakers who didn’t have access to film but studied them instead. Then I did performance art for ten years before I came back around to making experimental films.

Filmmaker: Can you describe the process of this film?

Andrews: It’s a very hybrid film. I’m continually force-fitting things together that most people don’t think go together — the live action, the animation, the music, various genres — to shoehorn together and switch between those elements. This script read well on paper, but after the first rough cut, I thought that it didn’t work. So I put the script away and went back to how I’d normally work on experimental film, which is like a collage process. It’s not a perfect movie but it takes risks and succeeds on its own terms.

Filmmaker: When it wasn’t working, did you simplify or reduce any of the elements?

Andrews: Some people suggested I simplify or take out major elements of the film. I learned from one of my mentors to ignore suggested solutions for problems, but to instead look at what the suggestions point to. So, Paul Hill (the editor) and I said, “How do we make what’s not working work?” When using all these different components, they want to fly apart, and we had to somehow make them stay together. But maybe this tension is what makes it fun for me. I think I’m kind of a maximalist. People have said I could simplify, but as an artist, that’s not who I am. With this film, it was like trying to design a house in the space of a boat. Trying to fit everything in, a kind of puzzle.

Filmmaker: What was most challenging about the process?

Andrews: I put so much into this film, everything I know about film, music, animation and narrative — three years from writing to finishing it. The shoot was three weeks, but we animated for almost a year. Sometimes it feels like that scene in Un Chien Andalou and I’m the guy dragging the pianos, because I don’t have a producer or distributor to see the movie through the stages of getting the movie seen; I don’t know very much about marketing, social media, the smart paths to follow, nothing really. I’m learning as I go. I have to remind myself that the film is an accomplishment, as a first-time feature filmmaker with the budget that I had, to finish it and then premiere at Rotterdam is huge. If I could go back, I’d have a script supervisor, there were scenes we missed shooting. I overscheduled. We shot in about 30 locations in 18 days. I’m actually a pretty competent editor and did my own rough cuts. Animation is a pleasure for me because it’s the kind of work I can do at my own pace. I also love making music and I love editing. My easiest days of shooting were when we didn’t have dialogue. Shooting dialogue was new for me…it was excruciating waiting around to re-light for each shot.

Filmmaker: What did you learn about directing?

Andrews: Someone said it’s the director’s job to make everyone believe in the vision. More than half our funding came from Kickstarter — we had to start there to get people to believe. I have been making experimental films for more than 20 years but this was the first time I was on a movie set, and I was the director! I learned how to make a million decisions a day during the shoot. Making a feature is a team effort, and I had a great team. The first day of shooting we were on at least six locations. At the end of the day, I thanked everyone and I welled up with tears because here were all these talented people working so hard to realize my absurd visions.

Filmmaker: How do you hope audiences will receive the film?

Andrews: I’m pleased when people laugh and cry, when they have fun. Also, there are important ideas in the film. I didn’t want to make a rhetorical film, but I want people to think about the limitations of understanding the world only through their own senses, and I want to open that up, to say that our perceptions are individual, and as a species, actually quite limited and subjective. And therefore, what we think we know might not be quite so fixed and solid as we believe.

Filmmaker: What about how your films are perceived is based on who you are, as an individual filmmaker?

Andrews: I made a decision early on not to be a “lesbian filmmaker.” I just want to be considered a filmmaker. It’s not that I’m in denial; I just don’t want that to be the big thing on my forehead.

Filmmaker: You moved to Maine 15 years ago. Has it been difficult to engage in the film world?

Andrews: I was afraid of falling off the map, that it would be the end of my visibility to the “art world.” But I don’t think that’s been the case. I may be missing out on a lot of networking kinds of things people do, but by nature, I’m not a schmoozer. So if I lived in New York, I’d probably just be holed up in an apartment somewhere anyway. It can also be discouraging in a big city when you see so many artists fighting for the same few scraps. In a small town, you’re unique so you don’t see or feel that. Now, most of the people I hang out with are not artists. And I like that. It enriches my thinking.