Back to selection

Back to selection

“Humor Is Always Butting Up Against Tragedy”: Sterlin Harjo on Mekko

Mekko

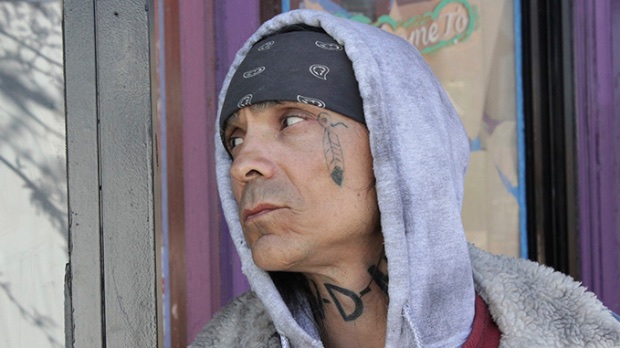

Mekko Premiering at the Toronto International Film Festival on September 13th, Sterlin Harjo’s latest narrative feature Mekko treads territory both familiar and new to this Oklahoma-based, Native American director. An ex-con-versus-thug thriller set in the world of Tulsa’s real-life Indian homeless community, the film stars Hollywood stuntman Rod Rondeaux and boasts an all-Native cast (many of whom are part of that aforementioned homeless community). Filmmaker caught up with Harjo prior to TIFF to talk about his fourth feature – as well as German Indian-philia, Herzog’s Stroszek, and Native humor.

Filmmaker: Mekko takes place in an Indian homeless community, and you use quite a few non-actors you actually met at Iron Gate, a Tulsa shelter. How wary were these people of letting you into their world? How did you approach them and gain access?

Harjo: I think in the Native community a lot of people know my films, so when I approach people in any native community I usually find fans of my work. There is an automatic trust there. They know I’m one of them. Native people, in general, have been so hungry for honest portrayals in the media and on film that they recognize me as someone fighting the good fight. Specifically, with the people from Iron Gate that I met, I really just told them the story I was going to tell. So many of them were shocked that a young man would be interested in telling a story that they are all so familiar with. Over and over people would tell me, “That’s how so-and-so ended up here. Just like in your story.” Even some people would say that the story (in my script) was how they ended up on the streets.

I also ran into a man on the streets that I hung out with in high school. A series of events led him to the streets. He was really helpful. He would talk to me about the philosophies of people on the street. He would even help protect us, because it did get touchy. There were a couple of times that other street people would come up and see us filming, there would be an actor that I made look like he was living on the streets — with dirt on his clothes and street-worn makeup – and understandably, they would get confrontational. When this would happen, and it only happened twice, the street people that I was working with would talk to them and tell them what we were doing. Then they would be cool. They saw that we weren’t just out to exploit life on the street, but were trying to tell an honest story.

Filmmaker: Not only are you and the cast of Mekko all Native American, but you also employed mostly locals in the production. Is it important for you to keep things local, or is this a choice that arises from budgetary necessity? Both?

Harjo: I’ve hired people from out of state before, but this film felt like it needed to be local. I wanted people that were familiar with Tulsa. If a crew member wasn’t Native, I wanted them to be familiar with Native people. In Oklahoma everyone is familiar with Native people – there are something like 38 tribes in Oklahoma. Over the years I’ve worked with local crew, and we have all developed a shorthand and camaraderie, so when I finished this script it was never a question of whether or not to hire local. It is a local story and Tulsa is a character. It made sense to hire an all Oklahoma crew.

Filmmaker: You’ve said that watching Herzog’s Stroszek inspired you to make this film. How so?

Harjo: Herzog in general inspires me and my work. I’m mostly inspired by his fearlessness. Even as an independent filmmaker you find yourself surrounded with films and filmmakers who are more concerned with money and the audience that they are trying to reach than in making original work. All of my films so far have dealt with a very marginal group of people, so the idea of money and an audience can’t be the main concern of my work. I have to be fearless and hope that if I tell good stories they will find an audience and relate to people from all walks of life. Through the years I have used untrained actors in my films. I use a lot of family in my films. Mekko alone has seven of my family members in it. My younger brother, Tre, even plays one of the leads. I had been kicking this idea (of Mekko) around in my head, and one night I re-watched Stroszek. The production struck me. I could feel that the filmmakers soaked up the environment that they were shooting in. They were shooting in diners that had actual customers in them and using real people from these locations as actors in the film. This is something that I have played with throughout my films, but never truly went for it. The scenes in which I did this in my past films have always been my favorites. Something about this inspired the story that I tell in the film.

I watched Stroszek twice that night, back to back, and just let it wash over me. I feel like I was infected by the filmmaking of it. Making a film about a homeless Native community and casting all actors would have felt like such a plastic unnatural thing. The auditions themselves would have been so offensive to my soul. This was the key I needed to tell the story – I needed to write a script in a way that I could absorb the environment. It had to be told from the point of view from the streets, not as an outsider looking at this community through a voyeuristic lens. In every business we shot in I used actual people who worked there, and insisted to the locations manager that we shoot during operating hours. We would just tell the business that we would stage outside and try to not interrupt too much. They were really into it. The people in the background feel natural because they were actually there. It helped bring a reality to the world I was creating. Without sounding like a Native film cliche, the story dips into the fantastical and surreal at times, so I needed everything else about the world to feel real.

Filmmaker: You’re a Sundance vet, yet your films also resonate quite strongly with the Euro film fest audiences. Though I hate to make a sweeping assessment of any culture, I’ve long wondered about this European fascination with Native Americans — if it’s not some part of a romanticizing (condescending?) of the American West. Germans in particular seem to have a bizarre history of American Indian-philia. Do you notice a difference in American versus international reaction to your work?

Harjo: Yes, Germans love us. When I was in Germany I felt a little like I was a disappointment. Like, it would’ve went over better if I had long hair and looked the classical Native part more. It wasn’t that bad, I felt it a couple times, but for the most part the audiences really respond to the films. I think European audiences are just as interested in authenticity when it comes to Native stories. When I showed my film Barking Water in Venice I was a little freaked out during the screening because none of the Indian humor was landing. That film is about a dying man, so the humor in it is the only way I can tell if an audience is following. During the screening the audience was silent. I sunk into my chair. At the end, a spotlight hit me and my producer and the audience stood clapping. I thought they hated it, but I realized that the drama and the love story is what they connected to. So it worked even without them understanding the nuance of Indian humor.

Filmmaker: Your last Sundance debut was the documentary This May Be the Last Time, and this is your third narrative feature, so I think a lot of folks would be surprised to learn that you’re also a founding member of the sketch comedy group the 1491s (described as a “gaggle of Indians chock full of cynicism and splashed with a good dose of indigenous satire” on the group’s Facebook page). Does comedy influence your dramatic film work and vice versa?

Harjo: Yeah, comedy is a big influence on my work. People who know me are surprised that I don’t make comedies. My idea of a great time is watching stand up or listening to Marc Maron interview a comedian about their career. I’m always finding the jokes in life. I feel that I do the same with my dramatic work. I find humor to hit better when it is couched within drama or tragedy. I mean, that to me is Indian humor. We are a civilization that has endured genocide in the most literal definition of the word, but we survived in large part because of our humor. I think that is inherent in Native people. Humor is always butting up against tragedy, and that’s what I aim to create.