Back to selection

Back to selection

Focal Point

In-depth interviews with directors and cinematographers by Jim Hemphill

“I’m Not Qualified For Anything Else”: Writer/Director Steve Kloves on The Fabulous Baker Boys and Flesh and Bone

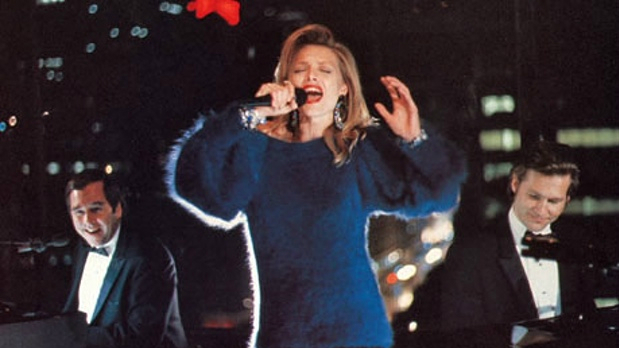

Beau Bridges, Michelle Pfeiffer and Jeff Bridges in The Fabulous Baker Boys

Beau Bridges, Michelle Pfeiffer and Jeff Bridges in The Fabulous Baker Boys Twelve years before he became the screenwriter of the most successful franchise in film history, adapting all but one of the Harry Potter novels for the screen, Steve Kloves directed the first of two extraordinarily powerful and original films – movies all the more remarkable for how different they were from each other. Kloves had one produced screenplay to his credit, 1984’s Racing with the Moon, when he assembled the dream cast of Jeff Bridges, Michelle Pfeiffer, and Beau Bridges to create The Fabulous Baker Boys in 1989. Its story of two piano-playing brothers and the singer that upends years of carefully constructed denial and repression is as complex and profound as the movies that made Kloves want to become a screenwriter in the first place – films like The Last Picture Show and Five Easy Pieces – but it’s also as unabashedly entertaining as a 1950s MGM musical. Gloriously lit by Fassbinder and Scorsese regular Michael Ballhaus, impeccably balanced in its combination of humor, music, and pathos, The Fabulous Baker Boys was the greatest directorial debut since Lawrence Kasdan’s Body Heat eight years earlier.

Nevertheless, it did nothing to prepare critics and audiences for its young director’s follow-up, Flesh and Bone (1993), a sun-drenched film noir about a brutal crime reverberating for decades in the lives of its perpetrators and victims. As different from Baker Boys as that film was from Racing with the Moon, Flesh and Bone was grim, frightening, and mesmerizing – at least to this viewer. Many were put off by the movie’s bleakness and poetic, allegorical nature, and Kloves left filmmaking for seven years, only to return triumphantly as the screenwriter of Curtis Hanson’s superb Wonder Boys (2000) before entering the world of Harry Potter a year later. In both breadth and depth, Kloves is one of the best screenwriters of his generation, but I’ve always felt that his gifts as a director are equally valuable and impressive. Now that The Fabulous Baker Boys has been reissued as a flawless limited edition Blu-ray by Twilight Time, I thought it would be an opportune moment to sit down with Kloves and ask him about the making of two American masterpieces.

Filmmaker: One of the things I found really striking about your first three films – I’m including Racing With the Moon here – is that they all felt so specific and detailed that I assumed they were drawn from personal experience, yet they were all so different I realized that probably wasn’t the case. Where did you come up with the original idea for The Fabulous Baker Boys?

Kloves: For me everything starts with character. You’re not old enough to remember this, but when I grew up in the 1960s there was this act Ferrante & Teicher. They were two guys who played piano and they would appear on things like The Ed Sullivan Show, and even when I was five or six years old I thought it was kind of a hysterical act. The idea just kind of nested in my head, and then years later I was at Disneyland at some kind of “roaring 20s” malt shop where there was a guy playing the piano – and he was really good. I started thinking about him, because I’ve always been interested in what you might call blue-collar entertainment – people who work in the arts in a kind of working class way. Another thing to remember is that in the 1960s everybody gave their children piano lessons, thinking it would give them culture – not that they would end up playing at Disneyland or a Holiday Inn. So those ideas came together in my head with the idea of telling a story about brothers; a lot of my stuff has to do with dysfunction in families, and I just thought this idea of brothers with a dying piano act would make a great movie. The handful of people I talked to about it at the time thought it was a completely bizarre, terrible idea for a movie, but it really took hold of me and I spent six months just writing notes about the characters and their relationship before I crafted it into a narrative.

Filmmaker: Did the piece require a lot of research?

Kloves: It’s funny, I read this quote by Mona Simpson once where someone asked her if she believed in research and she said, “Deeply. But I believe in doing it after the first draft.” That’s what it was like on Baker Boys. Obviously, it’s different if you’re doing a movie about World War II – in that case you should probably do a little research – but on this one I wrote the first draft just based on what I knew and could imagine from spending time in hotels and things like that. Then I went off and did the research and discovered that most of the time I was accurate, though sometimes things were stranger than I had thought.

Filmmaker: How do you structure your scripts? Are you the kind of writer who outlines or does index cards, or do you discover the story more organically as you write?

Kloves: Essentially I follow the characters, but on Baker Boys I did write a lot of cards that were scenes or incidents or moments. I then tried to put them in some kind of order on a board, but it didn’t really work. I’m not that kind of writer; for me character is plot. Maybe because I’m not that good at stringing together a plot! I remember Alvin Sargent said that what he wanted on his tombstone was, “Finally, a plot.” [laughs] But I do think that when it works, when you let character carry something, it’s exciting and has an energy that you don’t have in a more plot-driven film. It’s just a different kind of movie – I grew up on films like The Last Picture Show and Five Easy Pieces that work in that way…there’s a kind of drifting with intent.

Filmmaker: It makes for great movies, but I think sometimes it’s scarier when you’re writing without a road map. Do you ever get blocked and have a hard time figuring out where the characters should go next?

Kloves: Sometimes, but you have to rely on your instincts. If I’m interested in following the characters and seeing where they go in the next moment, I have to trust that the audience will be interested as well. As you know, most of the time when you’re writing you’re not really writing, you’re thinking. It’s tricky working that way, because when you do have a great plot it provides you a kind of North Star or a road, and if you’re relying on character they are the North Star and can take you into some unexpected places. But I like that, as opposed to writing an outline and then feeling like I’ve already taken the trip. With Baker Boys I didn’t always know where I was going, and you do go down some dead ends and then you have to back up and go down another street. It’s not a terribly efficient approach, but it’s the only thing that really works for me.

Filmmaker: Where was your career at at the point that you wrote the script for Baker Boys? Was it something you realistically thought you could direct, or did that come only when a lot of other people turned it down?

Kloves: I always wanted to direct it, and it was completely unrealistic at that point in my career. I had written one movie, Racing with the Moon, and I was twenty-five when I sold Baker Boys as a spec script to Mark Rosenberg, who was running Warner Bros. at the time. I actually worked with George Roy Hill for a while and he was great to work with, but he wanted to take it in a certain way that I wasn’t comfortable with. Eventually Mark left Warner Bros. to work with Sydney Pollack, and the two of them and Paula Weinstein became my angels because after working with me for a couple of years they got to know me and trusted that I could direct it. It still was hard to get made, because in those days even if a studio didn’t want to make something – which Warner Bros. ultimately didn’t – they didn’t want to put it into turnaround and watch it be a success for someone else.

Filmmaker: Had you always wanted to direct, or was that something that came out of your experience watching Richard Benjamin direct Racing with the Moon?

Kloves: I always wanted to direct, but the experience on Racing with the Moon made me want to direct sooner. I think that any writer is somewhat startled the first time they see their script realized, because you see the movie one way in your head and that’s not the way it ends up. It’s not like I was profoundly disappointed with Racing with the Moon, it just wasn’t what I saw in my head in some ways – though in some ways it was. In hindsight I realized how fortunate I was to have made Racing with the Moon with Richard. He was very respectful of the script and very good with actors, and I realized after directing Baker Boys that I wasn’t always able to get what I wanted on screen. It’s very easy to curse the director when it’s not you – and a joke I used to make on Baker Boys was that the writer wasn’t allowed on the set.

Filmmaker: It sounds like Richard Benjamin allowed you quite a bit of involvement though.

Kloves: He did. Some of the cast came out of discussions I had with Richard; I knew of Sean Penn, for example, and recommended that Richard look at Sean. Sean and I were really kindred spirits; we had seen the same movies growing up and wanted to make those kinds of movies, and discovering an actor like that was really interesting. I worked with him sometimes because if a line was uncomfortable for him he would come to me; often he was right that there was something wrong with the line, but I remember one time I said to him, “I think this line is right.” He went off and came back about twenty minutes later and said, “You’re right, it’s not that I’m uncomfortable with the line, it’s the character that’s uncomfortable in the scene. I should be uncomfortable.” What was great about that moment was that as a director I instinctively felt comfortable working with actors; I got to try it out on Racing with the Moon and audition myself as a director by talking with Sean. I didn’t know that’s what I was doing at the time, but when the time came to direct Baker Boys I had a confidence when it came to dealing with actors.

Filmmaker: Well, in my opinion Baker Boys has three of the greatest performances of all time from Jeff Bridges, Michelle Pfeiffer, and Beau Bridges. How did you assemble the cast? I have to assume that actors would have been dying to do this movie, since it’s so character-driven.

Kloves: You’re quite right. Whenever we would send the script out studio execs thought it was dreary and depressing; actors thought it was funny and moving. They saw the humor and pathos in it. I knew I wanted Michelle from the beginning and I knew I wanted Jeff. Even though I knew Michelle I was having a hard time getting a hold of her, so I went to Jeff first. I flew up to his ranch in Montana to sit and talk. He spent an afternoon asking me questions about the movie, and I answered all of his questions honestly and told him why I wanted him, and at the end of it all he said, “I’ve had very good luck with first-time directors.” He was in Robert Benton’s first film —

Filmmaker: He got nominated for an Oscar for his performance in Cimino’s first film.

Kloves: Exactly. So that was helpful, and Jeff’s a courageous guy anyway – he really goes by his gut. After he said yes I finally got ahold of Michelle, and she liked the script but she didn’t want to work – she had done a bunch of things in a row – so over the course of a week I just kept going over her house for coffee and cigarettes and wore her down. Then Jeff called and said, “I have an idea for Frank.” I knew what was coming. “What about Beau?” I said, “Look, I think it’s a gimmick. I love Beau as an actor and always have, going back to The Landlord, but not for this movie.” But I agreed to meet him at this place in West Hollywood called Hugo’s, where everybody used to go for pumpkin pancakes – I never understood the appeal of the place – and I just sat there trying to figure out how I was going to get out of this. Then I saw Beau walk into the restaurant, and it just hit me – he was Frank Baker. By the end of the breakfast I decided to embrace it, and it’s one of the better decisions I made, because at the end of the day it wasn’t a gimmick – Beau was terrific.

Filmmaker: It sounds like there was a lot of talking things through between you and the actors. Did you also have a rehearsal period?

Kloves: Yes, in those days you generally had two weeks of rehearsal – I just took it for granted. Beau was fascinating to watch for me as a first-time director, because in the first week of rehearsal he went back and forth between being very high and very low – very big and very small – and then at the beginning of the second week he suddenly found the sweet spot for the character and stayed there with perfect pitch for the entire shoot. Jeff and Michelle had different techniques, but the two weeks of rehearsal were essential for them as well and allowed us to hit the ground running; we did sixteen set-ups on the first day and it was clear that everything was just working. We also did other things before the two “official” weeks of rehearsal: the four of us went to a bar and watched lounge acts, Beau and Jeff and I rehearsed and did improvisations at Jeff’s house…I would set the scene for them saying things like, “Frank is twelve and Jack is ten, you’ve just heard your father died.” They also had to do a lot of preparation on their own just learning the piano pieces, because there were scenes where I wanted to start the camera on their hands and come up to their faces in one shot. Meanwhile Michelle was taking voice lessons, so it was kind of a like a boot camp. All of that combined helped the actors feel the DNA of the movie by the time we started shooting.

Filmmaker: In addition to fantastic actors, you had a great cinematographer in Michael Ballhaus. What was that relationship like?

Kloves: One of the advantages you have as a first-time director is that you don’t have a textbook in your head about how to do it – I just did what felt right and worked for me. The first time I sat down with Michael he said, “I think you’ve directed this movie in your script. I see the movie. What do you see in terms of the color palette?” I said, “You’ve probably heard this before, but I really think it applies to this movie: the colors should be like a Hopper painting.” I always saw the movie in terms of the burnished red of the booths, a kind of dark crimson with amber light and a slightly threadbare quality, like the surroundings are all going to seed a bit. We also talked about keeping the camera movement simple and motivated, not just sweeping the camera around for its own sake. I wanted to keep it simple both because I was a first-time director and because stylistically I felt it was right for the movie. We saved the more elaborate moves for moments we wanted to stand out, like the scene on the piano, which needed a different energy.

Filmmaker: Were there any unexpected challenges or struggles you faced as a first-time director?

Kloves: Baker Boys was kind of an outlier in a way. One of the producers, a guy named Bill Finnegan who had started with Howard Hawks and worked his way up, said to me, “Remember this movie, because you’re never going to have another one like it.” He was right. Flesh and Bone, which I would do a few years later, was much more challenging in every way than Baker Boys was. That’s something I learned about the movie business: each movie is its own culture and society, and you really don’t know what it’s going to be each time. There are too many live elements coming into a contained space and reacting.

Filmmaker: Since you brought up Flesh and Bone, let’s talk about it a little. It’s a very different movie from Baker Boys, more poetic and mythic and less literal. What was the starting point for that script?

Kloves: I had written this little fragment of a short story about a father who used his son in the commission of crimes. It was just this little piece of paper that followed me around and I never threw it out. I was thinking about what to do after Baker Boys and I wanted to do something different, and as you pointed out I like to write about very specific characters in very specific worlds. I thought about what it would be like to start a movie with this seemingly innocent boy who’s lost but turns out to be part of a scheme of his father’s. I followed that idea, but it was a very hard movie to write. The script was more allegorical than the movie we made — it had an early scene with the adult Arlis driving into a town and seeing a bullet-ridden sign reading, “You are now entering Grace.” I had conversations about it with the production designer and other people, and I think I flinched a little. I wish I hadn’t…I’ve always regretted backing off of the allegorical aspects, because I think some people didn’t understand what I was going for in that movie in terms of fate – the idea that what you’re seeing was always meant to happen.

It was a very intense movie in many ways, starting with the fact that my friend Mark Rosenberg, who I mentioned before, died on the movie. That was heartbreaking, and then you had the nature of that film, which was very dark and didn’t make for the kind of environment on set that we had on Baker Boys. It was a different set of actors and a different way of working for me – we had no rehearsal, which was brutal. Everyone came into the movie late. I did have another wonderful cameraman, Philippe Rousselot, and we did it in a whole different way than Baker Boys – as you say, it’s consciously more poetic, lit with a kind of aching beauty. It’s an interesting movie…it’s not everyone’s cup of tea, to the say the least. Some people really loathe it, some like it, and a few like it way too much – you wonder what it’s touching in them. [laughs] There are a lot of things I like in it, particularly Gwyneth Paltrow’s performance – I knew she was going to take off.

Filmmaker: Yeah, I vividly remember the impression she made on me when I saw the movie in the theater. It was like seeing Mickey Rourke in Body Heat or Eddie Murphy in 48HRS. – watching somebody and realizing instantly, this person is a star.

Kloves: The difference is that no one went to the movie, so it didn’t make that impression in the culture the way that it did in the two examples you cite. But what did happen is that I had all these directors visiting the editing room and saying, “I heard about this girl Gwyneth Paltrow” – it was getting around town, and other filmmakers would come and watch her footage on the KEM. Again, when the movie came out no one went, but there were screeners around town and people would talk about Gwyneth’s performance – I think they were just fast-forwarding to her, because she was the only thing anyone would talk about. We all knew what was coming.

Filmmaker: What was it like shooting with no rehearsal and having to work with actors of such varying levels of experience? You’ve got the gamut from kids and Gwyneth, who was nineteen, to James Caan. Then there’s Dennis Quaid, who’s somewhere in between.

Kloves: There were some problems, not all of them the actors’ fault. Dennis was my rock; he was very good very fast, though on the first day I made him do seven takes – even though he was great on the second – because I wanted to get him into a different head space than he was used to. He was so consistent and focused the whole time, as was Gwyneth, who hadn’t done a lot of movies but had worked a lot in theater with her mother. She had a theater actor’s perspective that the script is the bible, you know it and come to the set totally prepared. Jimmy Caan had a trickier part with a lot of long speeches; he certainly would have benefited from some rehearsal, because I would have benefited from it – we could have worked together a lot more. But he was very game, so I just had to create enough time on set for both of us to find the character. Meg Ryan came at everything from a very emotional place, trying to locate the center of this girl who had been orphaned at a young age, but I don’t think she was used to working the way I work, which is kind of intense. She was more used to working alone, and I like to get inside the actor’s orbit. Getting that close to Meg was tricky, but I do think she has beautiful moments in the film and did some things that she never did before and hasn’t done since. She was committed in the moments where she felt connected to the character’s emotions, but it was a very different situation from Baker Boys. Again, I think part of it was the type of movie, and part of it is that we all suffered from not having any rehearsal.

Filmmaker: Given that studios told you Baker Boys was dark and depressing, what did they make of the Flesh and Bone script when you sent it around?

Kloves: I definitely wouldn’t have gotten it made without Baker Boys, and the night before we started shooting Philippe Rousselot said, “You know, this feels like the movie you would have made before Baker Boys. It’s almost as if you want to make it even tougher on yourself.” When I wrote the script, people told me I could make it if I got one of five actors: Michael Douglas, Nick Nolte, Harrison Ford…I can’t remember the two others. Most of them either weren’t right or weren’t available, and sometimes the studio would give you the name knowing they weren’t available. I ended up at Paramount, which was the only studio in town that would let me make it with whoever I wanted. There’s no way it would have happened if I wasn’t coming off of Baker Boys.

Filmmaker: Was Baker Boys a big hit, or were you just hot because of the critical response?

Kloves: The decision was made to go out into 800 theaters on the first weekend, which at that time was a sizable release. On Monday morning, Tom Sherak at Fox called me – I’ve never gotten a call like this before or since from a studio executive – and said, “I made a mistake. We should have platformed the movie, and now we can’t recover from it. We’re going to have to pull it from most of these theaters next weekend. I’m sorry.” But Michelle got a lot of attention and won every award but the Academy Award, and by the time the movie came out on video it was huge – for a while we were at number two behind one of the Back to the Future movies. So there was a perception among people that it was much more successful than it was; it basically broke even theatrically, but everybody saw it on home video. Whereas Wonder Boys had the distinction of being released twice and nobody coming either time. [laughs]

Filmmaker: Did the failure of Flesh and Bone have something to do with why you took such a long break?

Kloves: It’s complicated. I spent three years on Flesh and Bone, and I think it played in the world for seventeen days. Then it came out on video with a horrible cover and nobody even rented it. I had lost my best friend, Mark Rosenberg, on the movie, and the movie business was dispiriting at that time for the kinds of movies I like to make. I was quoted as saying that I would rather spend time with my six-month-old daughter than a fifty-year-old studio executive, which is kind of glib but also has some truth to it. But at a certain point your six-month-old daughter is three, and you have to make a living. At about that time Scott Rudin sent me a book, and up until that time I had never wanted to do an adaptation – I had turned down every one I was ever offered, because I only wanted to write and direct originals. But I started to read this book, which was Wonder Boys by Michael Chabon, and thirty pages in I thought, “Oh my God, if this stays this good I’m going to have to write this.”

Filmmaker: How was writing an adaptation different from writing an original?

Kloves: It basically just really fucked me up. Alvin Sargent told me, “You’re going to find out that adaptations are at least as hard as originals, and actually more difficult in some ways because you have this thing there that you want to respect, and you’re killing someone else’s darlings.” It’s hard enough when you’re killing your own. Initially I had a hard time because I had this thought that if they were hiring me to adapt the book I shouldn’t use a lot of the book; I know that sounds mental, but I figured, why are they paying me if I don’t invent stuff? Then Alvin told me something else, which is that if a book gives you a lot, take it, because some books don’t give you anything – when he adapted Ordinary People, he stayed very close to the book, but on Paper Moon he only took one scene. With Wonder Boys, I finally embraced the book and just tried to bring it to the screen. It was a long process – something like two or three years before I had a script.

I fully intended to direct it. I’m still not sure why I didn’t. I just wasn’t in a directing head when we were putting it together, and I think I was communicating that in some ways to everyone around me. But reading that book is really what brought me back; I thought it was great, and that it would make a great movie. Before it was made people would say to me, “Oh, I love that book – but it’s not a movie.” “Sure it is!” I would say, though maybe they were right since no one went. I like that movie a lot though, and I think Curtis Hanson did a hell of a job directing it.

Filmmaker: Do you plan on returning to directing at some point?

Kloves: I do. I never meant to stay away this long. My one unfettered joy is working with actors on something I’ve written, and I’ve denied myself that now for a couple of decades. I’ve always had one foot out the door as far as the movie business is concerned, and I’m not sure why. I don’t think I’m the only one – there’s a tendency to want to leave it. But then you think, well, what else can I do? I’m not qualified for anything else.

Jim Hemphill is the writer and director of the award-winning film The Trouble with the Truth, which is currently available on DVD and iTunes. His website is www.jimhemphillfilms.com.